Yamuna – the name at once invokes the mystical and the mundane, the image of Yami the Goddess entwined firmly in the waters of the flowing river. Also known as Kalindi – the ‘dark one’, the river appears ordained for the grey waters that characterize her. It has often been described as the ‘lifeline’ of Delhi, even though a mere 2% (22 km) of its total length passes through the city. It is also here that the river has been proclaimed biologically dead! The death knell was sounded over two decades ago. Clothed in apathy and perhaps disbelief, we chose not to hear it.

The Yamuna originates at 6,387 meters at the Saptarishi Kund, a glacial lake at the base of the Yamnotri Glacier. It is joined by a second source of water, a massive hot spring, at a height of 11,000 ft. It flows through the Doab region forming a beautiful bow over a stretch of 1,376 km before merging with the Ganges.

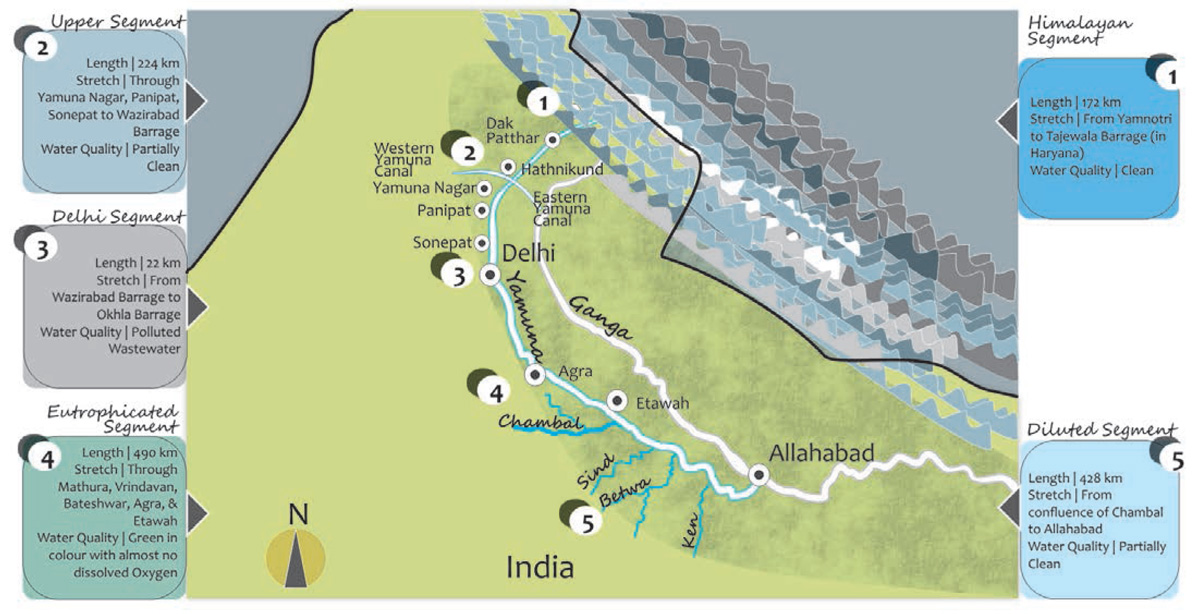

Scholars tend to divide its fluvial processes into five distinct zones – the Himalayan stretch, upper stretch, Delhi stretch, eutrophicated stretch and the diluted stretch. The Himalayan stretch consists of clear silver-blue water, while the upper stretch may be seen as already foretelling the bane that is to follow in the form of the Delhi stretch.

The river enters Delhi at Palla village after traversing a distance of 224 km. Here, at the Wazirabad barrage, the river is tapped for drinking water supply to Delhi. During the dry season, the entire available volume of water is diverted and no water is allowed downstream.

Over the next 22 km, no less than 22 drains empty their mostly untreated wastewater into the Yamuna.

Every day, 3,684 million liters of sewage flow through these drains into the river. For the major part of the year, the Delhi stretch carries not the silver-blue waters of the Yamuna, but a combination of sewage, filth, polyethylene, dead organic matter, agricultural residue, dissolved pesticides and domestic as well as industrial wastewater.

A study conducted by The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI) in the year 2012 found high levels of heavy metals (nickel, mercury, lead and manganese) near the riverbanks. In quantitative terms, this short stretch contributes over 70% of the pollution that afflicts the river. Water quality is often measured in terms of Dissolved Oxygen (DO) and Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD).Downstream, at Okhla, the DO level stands at a dismal 1.3 mg/l (recommended minimum being 4mg/l) and the BOD at 16 mg/l (permissible level being 3 mg/l).

Aptly, the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) has repeatedly called for moving away from a hardware-based approach to cleaning the river. The Yamuna Action Plan (YAP) that was launched in 1993 and is already in its third phase with meagre gains has adopted this approach. The alarming growth rate of the city (47% per decade) demands technologies, capacities and strategies that will help it to leap ahead. Localized bio-remedial measures for sewage treatment may yield better results than increased pipe-lengths and more treatment plants. The connect that exists between our daily life and our surroundings needs to be re-established. Each time the flush is used and the drains are used as a garbage dump, guess where the filth ends up? It is telling that under the first phase of YAP, 10-ft high barricades were erected along the bridges across the river to prevent people from throwing things into the river.

Three steps emerge that are essential for rejuvenating the river. Delhi needs to manage its waste better and ensure that untreated wastewater is not dumped into the river. The city also needs to use its water more efficiently and equitably by better controlling huge distribution losses and reducing per capita consumption.

This may result in a ‘real’ river with flowing water within its banks. Finally, the citizenry needs to develop a sense of urgency for the task at hand. Many citizen-based organizations (Swechha jumps to mind instantly) have been active in this area but their efforts may have been disparate. A vision document that cuts across disciplines – hydrology, ecology, toxicology, planning, engineering, governance, sociology and philosophy – and promises to restore the riparian landscape of the river is imperative for a lasting change.

Her natural drains, wetlands, forests and aquatic life need urgent restoration.

However stark her condition may be, in people’s minds, the Yamuna is still the powerful absolver of sins. The personified river goddess weaves her way in and out of the metaphysical and the palpable. In the Vedic tradition, Yamuna is the daughter of Surya and Sanjna and twin sister of Yama the god of death. In the Puranas, she is the mystic companion of Krishna, the divine cowherd who spends the entire day by her banks. The Puranas tell of another epoch in time, when the waters of the Yamuna had turned dark, venomous and seething (one cannot help but connect the present with the past that it appears to be revisiting). The village folks were too frightened to drink or bathe in her waters (the current grading of the Yamuna waters at the Delhi stretch is ‘Class E’ that implies that the water is not fit for drinking or bathing, but only for industrial cooling or irrigation). The naga Kaliya had taken refuge in its waters in Vrindavan (literally, the forest of sweet basil). The young Krishna conquered the hooded snake and banished him from Vrindavan.

The Yamuna flows on, continuing to the eutrophicated stretch, where the water is visibly green. The Taj Mahal looms over the river at Agra, perhaps silently trying to find a parallel between the green amalgam and the silver- blue waters of yore. This segment is marked by the unusually large presence of algae and phytoplanktons. At night, respiration brings about a drastic reduction in the oxygen levels of the river and jeopardizes the survival of other aquatic life. The stretch is also dotted with places of religious significance – Vrindavan, Mathura and Baleshwar – where ritual dipping in the holy river further contributes to loading the river.

Eventually, the river trundles along to its final segment – the diluted stretch. Reinforcing nature’s way of restoring hope and life, the Chambal infuses the green river with a gush of freshwater. Though not quite enough to completely revive it, the waters of the Yamuna appear to put on the dark silver sheen again. Perhaps to convey that there is a silver lining yet.

Anamika Prasad is an expert in the field of Environmental Design and Sustainability. She is the founder and director of EDS, environmental design consultants in Delhi.

Comments (0)