You have been the mayor of Curitiba three times and governor of the state of Paraná twice. How important is it for politicians to understand urban design strategies and for urban planners to understand political systems?

One of the most important issues regarding cities today is to make things happen. There is an overall paralysis that comes from constraints from many sides – bureaucracy being the main cause – but also from a fear of proposing something. To innovate is to start. We must have a certain commitment to simplicity and even to a degree of imperfection. I once read a phrase that touched me deeply, which was roughly something like this: “I’d rather have graceful imperfection than graceless perfection.”

Planning is a process that can always be corrected if we pay attention to feedback from the people.

We should imagine the ideal, but do what is possible today. The roots of a major transformation lie in a small transformation. Start creating from simple elements that are easy to implement and in future these will serve as embryos of a more complex structure. The system that became known as BRT (Bus Rapid Transit) and is nowadays present in over 200 cities worldwide started in Curitiba with one dedicated lane transporting 20,000 people. It evolved to an integrated transit network carrying over two million passengers per day. The contemporary world demands increasingly fast solutions and it is the local level that can provide the quickest responses.

|  |

|  |

Rua das Flores (Street of the Flowers): the first Brazilian pedestrian street planned in 1971 by Jaime Lerner during his first legislative period as Curitiba’s mayor | |

I emphasise these points because this is where designers/planners and politicians need to find common ground. The lack of resources cannot be an excuse not to act. Some cities have seriously compromised themselves, even when resources were plentiful, with costly and equivocated interventions; elevated roads and rivers encased in concrete are good examples of that.

If you want creativity, cut a zero off from your budget. If you want sustainability, cut off two!

However, it is necessary to have a guiding strategic view, a future scenario. Plan for the people (and with the people), not for centralising bureaucratic structures.

Urban planning is not a product; it is a process, with a long-term timeframe. It takes time and it needs to. Politicians must understand that and have this perspective of future objectives as the guide for present action, that is to say, to bind the present with a future idea. Planners, on the other hand, need to understand that the present belongs to us and it is our responsibility to open paths, understand the needs of political timing and the fact that if politicians disregard the daily demands of the citizens, they will lose the essential support of their constituents and will not accomplish much. Balance has to be reached between the quotidian needs of the population and the prospects of their city.

A fertile convergence ground is possible through the concept of ‘Urban Acupuncture’. These quick, precise, focused interventions help generate new energy and synergy for the entire city. These acupunctures can give visibility to the long-term objectives of the planning process and provide the politicians the necessary short-term demonstration effect.

I was fortunate to be able to understand that cities are for people and must be designed to their scale and I was able to share this vision with an amazing group of like-minded professionals. Together, we were able, with the involvement and support of the population, to translate this into a shared dream for the city and make it a reality. Leadership is important, but transforming a city is a collective endeavour.

You helped to create the IPPUC – Institute of Urban Research and Planning of Curitiba. How important is it for cities to collaborate with knowledge and research institutes in order to explore better solutions to our cities? Do you think that if today’s technical knowledge (like Smart Cities), had been available earlier, the solutions you implemented 20-30 years ago would have been different?

I believe that research and practice are the two sides of a valuable coin and should go hand in hand as much as possible. That does not mean that the production of knowledge must always have a ‘utilitarian’ goal, but that a wedge, a wall of incommunicability, cannot separate the world of academia, of research and the world of professional practice. Institutions are as good as the people who are a part of them. IPPUC played a key role in the development of Curitiba, helping to safeguard, from a technical standpoint, the long-term guidelines of its structure of growth. In addition, it has worked as a ‘project bank’, which is very important to help capitalise investments for the city in tandem with the established priorities. These are some of the roles it has played throughout its history. Universities are, naturally, institutions dedicated to the generation and diffusion of knowledge and they have in their hands the amazing enthusiasm and idealism of youth, which is to be nourished and allowed to flourish. In teaching, I always believed in the role of architects as ‘professionals of proposals’ and tried to encourage that as much as possible. Fortunate is the institution, the city, the country that manages to build bridges between the realms of academia/ research and the realm of the practitioners.

For me, the true ‘smart city’ is the one that intelligently uses its planning to integrate life, work and mobility into a sound structure of growth; that conciliates its design with nature and promotes the mixture of urban functions, of income levels, of ethnicities, of age groups, to strengthen its identity and foster coexistence and solidarity.

It is in the conception of cities that the largest and most significant contribution to a more sustainable society can be made.

Technology is an important tool, but it will not solve urban problems on its own. In that sense, I believe the examples of Curitiba hold great validity to this day.

Let me give you an example. When we were developing the ‘tube stations’ that are part of the BRT system (the elevated platform for the passengers boarding and alighting), there was a safety concern, as the doors of the bus needed to be perfectly aligned with the doors of the station before opening. Several technological solutions were presented, but their cost was prohibitive for us. We decided to conduct a test with one of the most experienced bus drivers we had and ask for his feedback on the experiment. The solution he pointed out was of incredible simplicity. If there was to be a mark on the side of the bus, and a mark on the side on the station, when the two of them were perfectly aligned, that meant that the bus was in the correct position and the doors could open. Problem solved at a minimal cost and a lot of ingenuity. I say that because I have been seeing so much effort invested in, let’s say, driverless cars. Driverless cars will not do much to solve problems of urban mobility, because the focus is still on private, individual transportation: driverless or not, they will continue to clog our roads and demand precious space within the city. Solutions for mobility are, structurally, on a more compact urban design, on the proximity of work and home, on the priority of public transportation and the pedestrian scale. ‘Smart’ technologies are only as smart as the use we make of them.

Your work as a politician and an urban planner has had a strong focus on creating equity and prosperity. The Brazilian law ‘The City Statute’, which has been created by means of a participatory system, safeguards the right to the city and citizen participation. How do you experience the usability of this law for urban development and in particular regarding the assignment you’ve been given by the current Mayor of São Paulo to develop ideas for its downtown area?

Every city must build a shared dream, a vision for the future, which is to be created collectively, so it can have the essential support of the population. Once this desired scenario is set, it is necessary to set up the means for its implementation, which I call ‘co-responsibility equations’. The name says it all: it’s about how the government, the private sector, civil society and all actors involved will share the responsibilities of making these dreams come true.

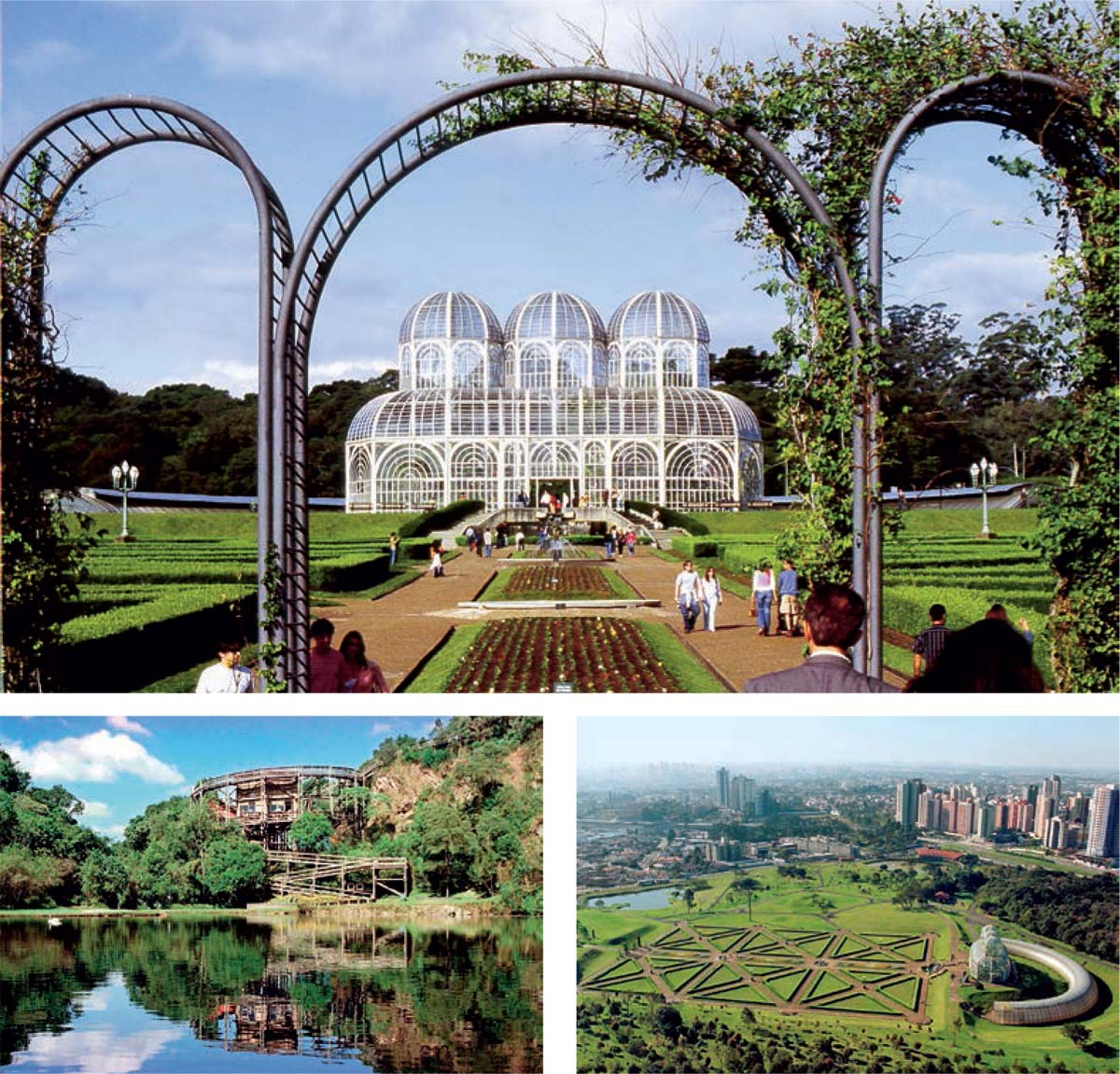

Some examples from Curitiba can illustrate this point. In the early 1970s, the city had a meagre 0.5 sq. m. of green area per inhabitant and a single public park. To change that, many strategies were implemented in the following years. To increase the presence of trees along the sidewalks, the city created a campaign in which it provided the planting of baby trees and the residents were invited to water them daily, ensuring their survival. These trees grew to form a most beautiful canopy along many of Curitiba’s roads. Many remnants of important green areas were located in private properties throughout the city. We envisaged a legal mechanism and fiscal incentives for the owners of these areas to preserve them, transferring the building coefficient to more apt parts of the city (a mechanism that was later absorbed in the City Statute), creating private urban reserves open for visitation or incorporating them in larger public parks.

Environmentally degraded areas, such as exhausted quarries, were rehabilitated to become healing ‘urban acupunctures’ for the city, such as the Parque das Pedreiras, with an incredible open-air concert venue that has hosted the likes of Paul McCartney and the Three Tenors and the Opera de Arame Theatre, which is part of Curitiba’s cultural scene.

Because of co-responsibility equations like these, though the population has more than tripled since the 1970s, the ratio of green areas per inhabitant is now more than 50 sq. m.

The City Statute is a useful instrument to provoke the necessary discussion of a strategic vision for the city involving the whole of society and it has many helpful mechanisms to help implement the constructed scenario and even-out some imbalances. However, as with any legislation, the support for its implementation will be under the watchful eye of society and the institutions, governmental or not, that have been created. São Paulo is an incredible, vibrant metropolis and it has made a serious effort in the past years to face the towering challenges of mushrooming urban growth in a very unequal socio-economic context. It mirrors the effort of contemporary Brazil to engage competitively in the global economy and at the same time face its historical injustices. It is huge work and I’m very enthusiastic about the partnership with the Municipality in developing ideas for its downtown area; hopefully it will bear fruit for the city!

In your understanding, cities are not a problem but a solution, which is an integrated structure of life, work and mobility. Climate Change is challenging our cities and its inhabitants are facing the consequences. Do you think that the solutions for climate change could improve the quality of people’s life and could it draw scenarios for Cities for All?

Cities are home to more than half of the world’s population and urbanisation is still rising; they are engines of economic growth, are responsible for about 70 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and have the level of government closest to the people. Therefore, it makes sense that it is in cities that the most significant contributions towards fighting climate change and improving the quality of people’s lives can be made.

I like to use the metaphor of the turtle to illustrate how cities must be an integrated structure of life, work and mobility. The turtle carries her life with her wherever she goes: she lives, works and moves ‘together’. Also, her shell resembles an urban tessiture. If we break her shell into pieces, living here, working there, leisure elsewhere, the turtle will die. And this is what has happened to many of our cities and it is a recipe for fragmentation and waste: waste of time, waste of energy, waste of creativity, waste of life. Waste is one of the largest contributors to our unsustainability as a civilisation.

A few years ago, I made a short film, called A Convenient Start, in the wake of Al Gore’s documentary (An Inconvenient Truth), aiming at translating key concepts of sustainability for children. The main idea was to combat the sense of hopelessness and focus on what we know about the problem, instead of on what we do not know. And to illustrate how each one can help by reducing the use of the automobile, separating the garbage, living closer to work or bringing the work closer to home and giving multiple functions during the 24 hours of the day to urban equipment. I argue that sustainability is an equation between what is saved and what is wasted. The less the waste, the higher the sustainability will be. And a lot can be done in this regard.

Bottom Left & Right: Free University of Environment (Universidade Livre do Meio Ambiente)

It has been a common approach to deal with growing cities to meet the evolution of ‘demand’ with increases in scale. So it is in the account of ‘excess’ people and lack of resources that urban problems have been debited. It is a quantitative problem. According to this simplistic reasoning, in case of urban congestion, for instance, if there was more money, we could appropriate more areas to build bigger overpasses to address the increasing ‘needs’ of automobiles. If there were resources we would win the race in relation to demand and everything would be solved.

This misconception has to be fought with the understanding that ‘cities are human constructs for humans’. A more humane city is the one that focuses on enabling for its inhabitants a decent offer of housing options, an efficient public transportation system, public spaces and community facilities, ample possibilities of employment, self-development and expression.

Finally, I’d like to close these arguments with a factor that is often overlooked when discussing quality of life in cities, which is ‘duo identity-coexistence’. Identity is a major element for quality of life; it represents the synthesis of the relationship between the individual and his/her urban habitat. Identity, self-esteem, a feeling of belonging are intrinsically connected to the points of reference people have in their own city, be it built heritage, natural landmarks or cultural manifestations. These references have to be treasured and illuminated. However, identity cannot exclude diversity, respect for others, the need for tolerance and coexistence.

Cities are the refuge of solidarity. They can be the safeguards of the inhumane consequences of the globalisation process.

On the other hand, the fiercest wars are happening in cities, in their marginalised peripheries, in the clash between wealthy neighbhourhoods and deprived ghettos. Heavy environmental burdens are being generated there due to our lack of empathy for present and future generations. And this is exactly why it is in our cities where we can make the most progress towards a more peaceful and balanced planet. We must fight for Cities For All, or it may very well be all for nothing.

Curitiba

Curitiba is the capital of the state of Paraná, the largest city in Southern Brazil with more than 1.8 million inhabitants in the city itself and about 3.2 million in the metropolitan area.

Curitiba was born in 1693 from the combination of natives and Portuguese immigrants. In the second half of the 19th century waves of European immigrants arrived in Curitiba, mainly Germans, Italians, Poles and Ukrainians. Due to fast economic and urban growth, Curitiba was listed in the 1970s as a city of slums, which also had the worst traffic jam issues among all cities in Brazil. It also had other environmental issues like floods and over population. Jaime Lerner changed the city’s planning fundamentally. The city is now one of the most beautiful and well organised in Brazil. In 1996, Curitiba was named as one of the most innovative cities in the world. In 2010 it was bestowed with the Global Sustainable City Award.

City Statute

The City Statute, approved in 2001, has unique qualities that are not confined to the high quality of its legal and technical drafting. It is widely regarded as a crowning social achievement, which took shape gradually in Brazil over a number of decades. The Statute seeks to bring together, in a single text, a series of key themes related to democratic government, urban justice and environmental equilibrium in cities.

Bringing previously existing piecemeal laws together under the aegis of the City Statute, with the addition of new instruments and concepts, it helps to facilitate a better understanding of the urban question. Most importantly, the Statute has led to the introduction of a genuinely national approach to dealing with the problems of cities.

Comments (0)