In a city like Mumbai, being able to afford a piece of land is an ambition for many, but being able to afford a piece of open sky above is a dream few people experience. As 20,500 (Census of India, 2011) people jostle for space per sq. km. of Mumbai, the city has managed to give back a measly 1.24 sq. m. per person of open space, equivalent to slightly more than three times the page spread of your favourite Indian morning newspaper. With the recent relaxation of Coastal Regulation Zone rules one can expect a rapid depletion in the natural open spaces in the city as well. In the post Covid era, what role can then be played by civil societies in one of the densest Asian cities to ensure that its citizens from all walks of life have free access to planned public spaces in their neighbourhoods?

Natural open spaces are assets to the city; this fact was realised a little too late. For the longest time, natural open spaces were treated as undeveloped land. Today, cities like New York, Delhi and Mumbai struggle to preserve their natural open spaces while timely policy interventions have restricted development in cities like Hong Kong and the Tokyo Metropolis on a relatively compact urbanisable land.

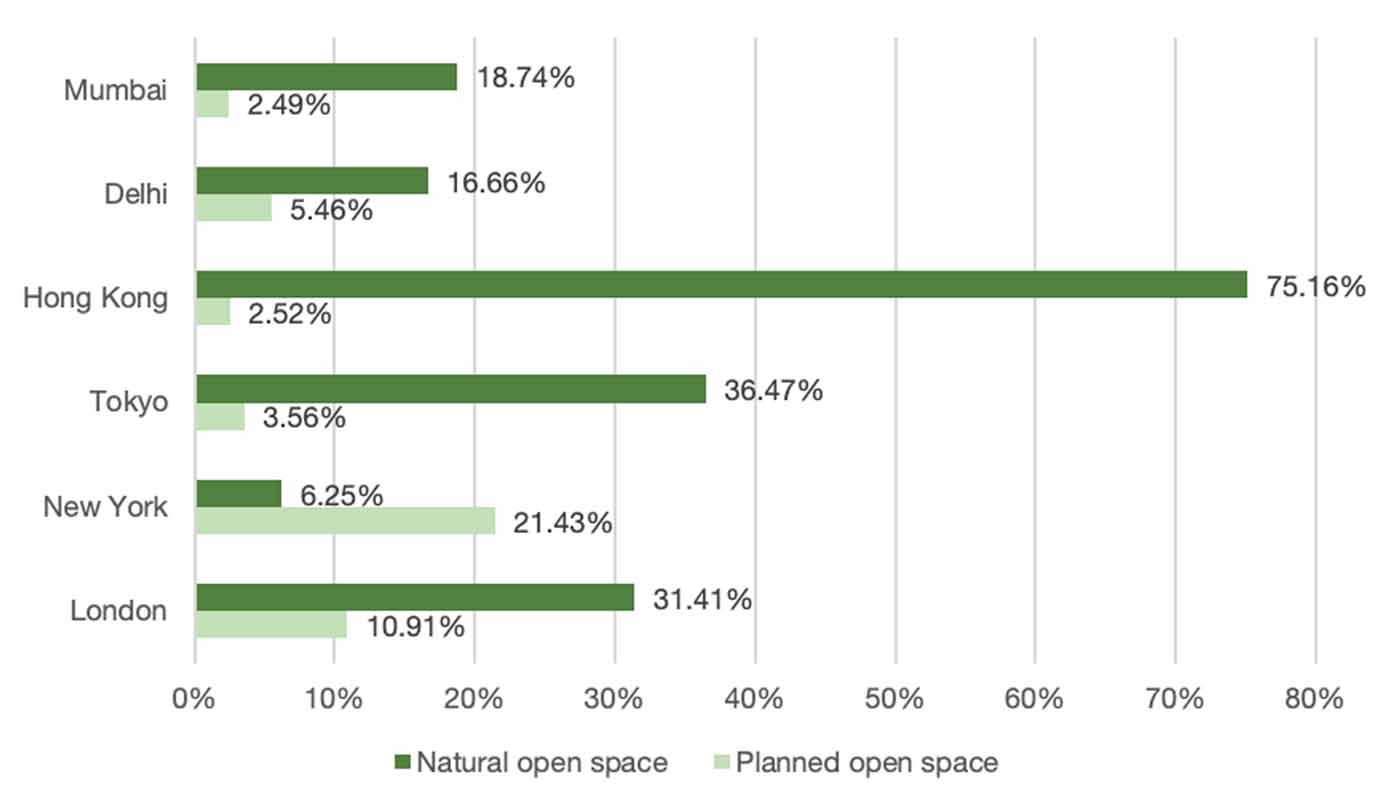

Almost all of the metros of the world are dense cities with most of their land already built upon. This makes land precious and also one of the most expensive resources. Increasing the amount of public open space to meet the existing population and to match the rise in population in such metros is a great challenge. The graph is extracted from a forthcoming book, 6 Metros: Urban Planning and Implementation Compared co-authored by Shirish Patel, Oormi Kapadia and Jasmine Saluja. It gives an insight into land area reserved as both natural open space and planned public open space of the city land area.

Disparities between the percentage distribution of natural open spaces and planned public open spaces is striking in Hong Kong as the city has unbuildable land in abundance and unusual in New York as the city has limited natural assets. The fact remains that these spaces have limited accessibility and do not fit into the everyday requirements of providing the necessary outdoor experience to city dwellers. Mumbai is cringing and stumbling in making adequate provisions under its out-dated open space policy, thus less than 2.5% of the city area is utilised as planned open spaces for the public.

For the longest time, natural open spaces were treated as undeveloped land

Increase in public open space in a city like Mumbai is rarely achieved. A tool of Transfer of Development Rights is used where a certain amount of public open space is mandated during redevelopment of private land. Another tool that has given limited results is Accommodation Reservation. A part of existing vacant private plots is reserved for public amenities and handed over free of cost in exchange of development rights. Further, Government relaxations to developmental norms in exchange of monetary compensation to the municipal authority has led to this acute shortage of open spaces.

On one hand the under planned open spaces are poorly maintained and on the other hand, there are many pieces of public land and infrastructure lying defunct in the city that could easily be converted into open spaces, but there exists no policy mechanism that would enable this.

Mumbai has a single tier city level planning mechanism and local bodies have a limited role to play that does not go beyond maintenance. As local area planning is completely missing, the local citizen groups are not empowered enough to carry out impactful changes on the ground besides making small-scale, sponsored tactical urbanism initiatives. In the absence of the open space policy and lack of decentralisation of the urban planning system in Indian cities, it’s treading a tightrope situation between meeting global goals and local needs.

The authors, as a part of a multi-disciplinary team of urban practitioners, identified an underutilised, rarely used public open space and took up the challenge to revive it with place making strategies. Place making ensures that open spaces remain open and are not encroached, built upon and eventually lost in the absence of a local area plan. The process that was followed attempts to generate a systemic framework to encourage many such projects to be taken up by concerned citizens within their neighbourhoods after being endorsed by the municipal authority.

Mumbai city is divided administratively into 24 wards, which are further sub-divided into 227 councillor wards. Councillors are directly elected and are responsible for maintenance of the open spaces, roads and other physical infrastructure of their wards. After identifying a derelict piece of land marked as a public open space in the City Development Plan (DP) in the Councillor Ward no. 226 at the southern tip of the Island City, a team of urban designers approached the councillor of that ward. This piece of land, triangular in shape was flanked on one side by the iconic World Trade Centre and an abandoned half-constructed building site on the west by the Arabian Sea; on the south it shared its edge with a slum and on the north was a street that culminated in a dead end. This end of the street was used as a parking lot. All in all, there was not much activity around it and the land was being abused as a defecating ground and drug peddler’s haven. However, it had a great potential to be a melting pot for the varied economic groups that lived in the area.

Dharya Garden is designed as a park for all. Infants in prams to specially-abled in wheelchairs use the fitness ring in the park that is designed to be at the same level as the pavement. A sunken sea-facing amphitheater with a built in stage doubles up for performances and open classrooms used extensively by the children from high rises as well as the slums. A modern seating system and a gazebo surrounded with plantation allow users to unwind and appreciate the view of the setting sun overlooking the Arabian Sea. Here, one has the luxury of practicing yoga by the bay in the yoga pavilion. The yoga pavilion is a covered space that can be used throughout the year for various purposes. A tree-lined fitness trail welcomes health enthusiasts to meet their daily step counts while the adult outdoor gym sets challenging goals for the more dedicated ones. Located in the centre of the park is the kids play zone with a guiding game trail connecting play equipment and traditional floor games like hop scotch. Leaving no one behind, the park also has a special area for dogs. Wet waste is converted into compost within the garden, and consumed.

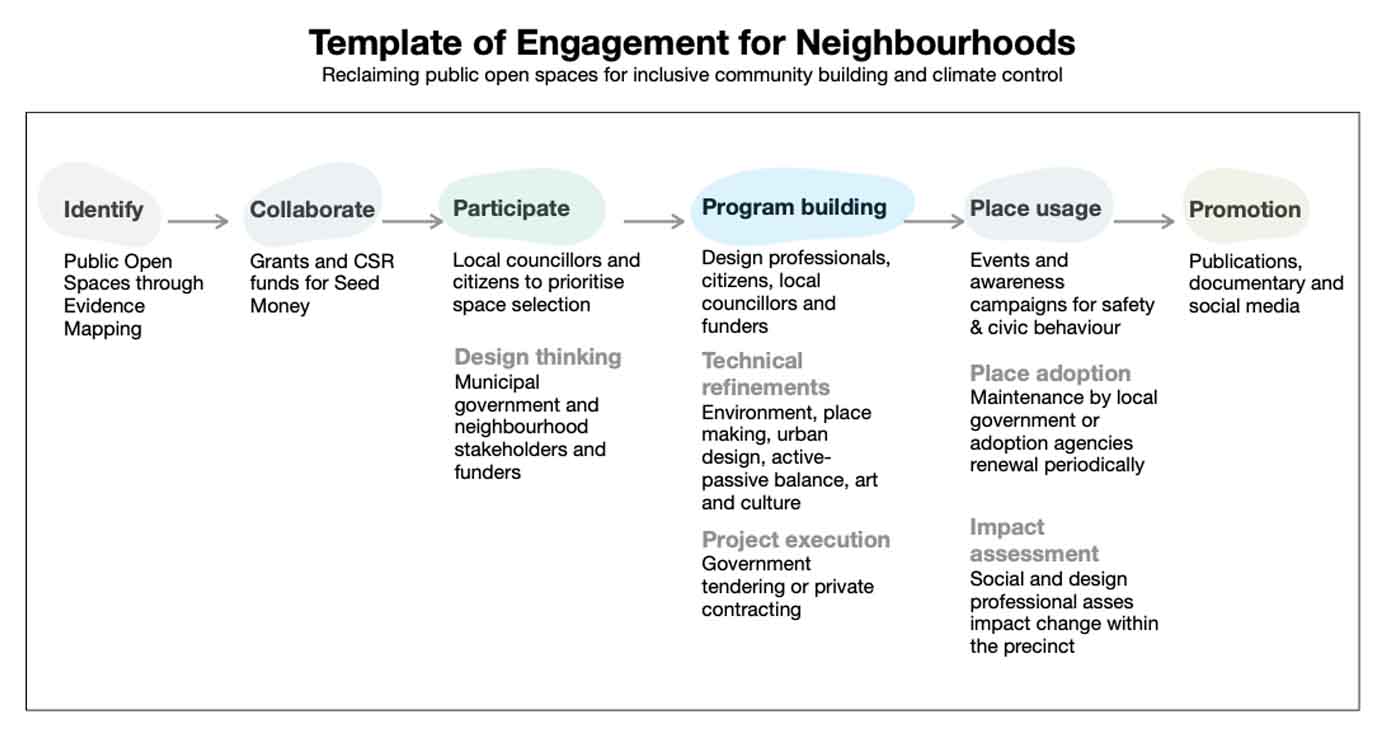

The park today has withstood Covid times bringing a breath of oxygenated air especially to the nearby slum dwellers. This space will hopefully merge social silos and encourage exchange of cultures. There is a need of repeating this success story of place making in all wards of Mumbai. This social experiment generated a Template of Engagement (TOE) so that many such defunct, abandoned and underutilised pockets in the city can be identified and designed for better utility by multiple stakeholders and bridge the amenities gap.

Mindless beautification schemes are superficial and reduce the utility of the space

TOE facilitates public participation through direct engagement with affected stakeholders, urban professions, NGOs and CSR verticals of business houses with elected representatives and government departments to bring about a visible change in the urban landscape at the neighbourhood scale and sensitise citizens with experiential outcomes. Local bodies have limited funds to support design thinking, conceptualisation of spaces and project detailing for their better utility. Issues like inclusive community building, access for all, women’s safety, child-friendly design, reducing the heat island effect and creating a sense of belonging and ownership towards the space are rarely addressed. Mindless beautification schemes are superficial and reduce the utility of the space.

|

Cities like London and New York have dedicated departments at their borough level for urban planning and design. Public and community spaces are mindfully designed for utility and at the same time delight their users and visitors. Policy amendments and organisational restructuring are long-term solutions that require political and governmental support simultaneously. Acceptance of public partnership models and endorsement of new ways of operation to activate grassroots level changes have the potential to align and shape future modifications to the policy. This is where a ready-to-use template like TOE becomes handy for concerned citizen groups.

Though it took more than two years to pull out Dharya Garden from the shadows of the World Trade Centre and return it to its actual users, it will hopefully introduce a comprehensive model process at the councillor ward level that will enable many such parks to be generated relatively easily through the city. If this model is institutionalised the onus will lie in the hands of the people to revive and conserve their neighbourhood greens. This shift in the process besides objectively adding more usable public open spaces may reduce urban segregation. Contextualised spaces create an outdoor culture as the surrounding community programs these places. The relationship evolved between spatial design and the social environment has increased the park usage; this has been a learning curve.

All Photos: Jasmine Saluja and Oormi Kapadia

Comments (0)