The term ‘informal city’, suggests a direct binary to the ‘formal city’. I have always had a problem with this binary, because these dimensions are inextricably diffused. Is this binary borne out of the inability of experts to address spontaneity in our cities, or conversely the disinterest of scholars and theorists to engage in mainstream practice? Isn’t ‘informal city’ and ‘formal city’ a false dichotomy to begin with?

Formal-informal is indeed a false dichotomy; they are too intertwined to separate. The proponents of this false dichotomy have marginalised and displaced the (leftover) others and privileged the formal. Even formal institutions (that include politicians, policymakers, planners, designers, scholars and ‘experts’) are run by people who switch between their official roles and selves, operating outside the rules, at times to achieve the spirit of a rule and at other times for personal gains. They operate within and outside the structure, mediating between the rules and technocracy and ordinary people. Informality cuts across formal practices and vice versa.

As revealed in my investigation of the attempts to redevelop Dharavi, Mumbai there is no sign of it becoming like the adjacent business district, the Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC). However, the former seems to seep into the latter in the form of teashops and mobile vending catering to the needs of workers in the high-class BKC. In short, the occupants of the formal are able to enjoy a better space because those who subsidise their lives reside in ‘informal settlements’ that require fewer resources to reproduce themselves. The formal of the middle classes are produced and reproduced through the informalisation of the leftover after carving out the formal. Settlements like Dharavi are legible to their inhabitants. It is the politicians, professionals and developers who are unable to read these. This illegibility provides protection to these settlements.

The city is not a total, unified entity. It is a set of phenomena, processes and systems, understood as ‘urban’. The state and planners (re) produce cities using categories such as land uses and systems such as housing and transportation. Yet, the city in practice is far more complex than this.

A city is continuously produced and reproduced by a multitude of actors both physically and perceptually via everyday practices (people’s spaces). It is imperative that the state, embodied in the notion of formal planning, figures out how to engage with what it calls ‘informal’, beginning with settlements and housing, not least because in many cities they represent the majority.

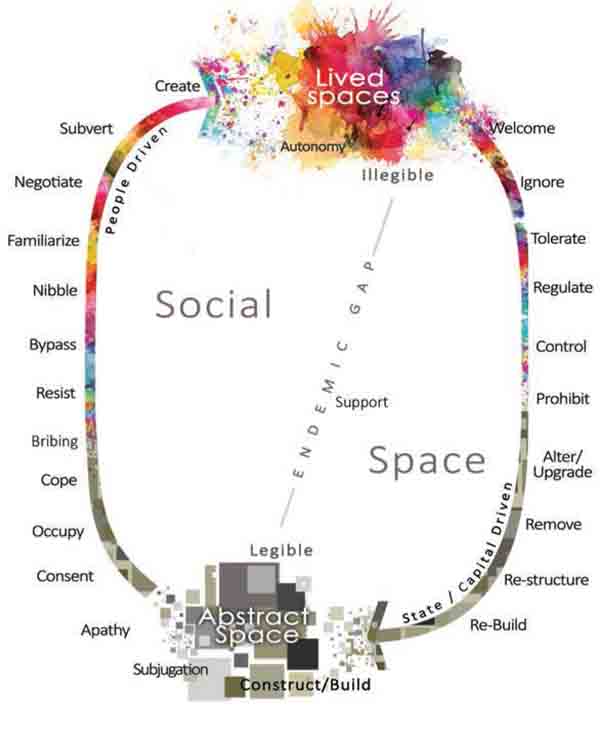

Your book People’s Spaces elaborates on the various ways in which cities are claimed, appropriated and owned by commoners. What are the key ideas of this book? What are its main takeaways?

People’s Spaces aims to find, make visible, acknowledge and critique the spaces produced and negotiated by ordinary people for their daily activities and socio-cultural practices, from perspectives closer to the creators. Ordinary people in this study are those who do not have the power to produce abstract spaces and/or to erase other spaces and histories as the state and capital. It is impossible to fully know how the commoners claim, appropriate and own parts of cities, as their tools are not formal. The work acknowledges that there is a lot that we do not know and that cannot be theorised using formal theories.

Colombo, Sri Lanka was heavily transformed between the 1860s-1880s. The fort was demolished, the harbour was expanded, hotels were introduced and a residential and cultural area for the colonial community was built. As it documents the transformation caused by the minority colonial community, the literature erases locals from history. This way of understanding the urban, I think, is incomplete and discriminatory. My examinations reveal that the Sri Lankans had caused an even bigger transformation in Colombo which I call ‘indigenisation’. Women too ‘feminised’ the city. Although it is impossible to talk about everyone in the city, leaving out the majority does not provide a grounded understanding of the city or its transformation.

The state- and capital-centered scholarship is unable to clearly see people’s spaces or their significance. This prompted me to investigate the people’s role in urban transformations.

Space produced by the state and capital is built upon abstract categories such as populations, land uses and housing systems. Yet people do not live in or use abstract categories such as transportation systems and land uses.

People use and live in (familiar) spaces such as parks and homes they can recognise. The gap between available or provided (abstract) spaces and spaces used by people makes urban space impossible to occupy without changing. Hence the paradox: abstract space is meant for use but use changes it.

The key switch adopted in People’s Spaces is not to view ordinary people as docile bodies or ‘victims’ of abstract space, but as ‘survivors’ of wars, tsunamis, colonialism and patriarchy and agents of change with transformative capacity. Adopting an empathic approach, rather than sympathetic, it looks beyond survival strategies adopted by victims into the negotiation of space for daily activities and cultural practices carried out by survivors, somewhat on their own terms. This displaces the formal-informal duality.

One of the key aspects of urban informality is its incredible resourcefulness within limited means, as is evident in what are called slums and squatters. What are some examples that stand out for you and what can we learn from them?

Informality is resourceful in a greater sense than what is acknowledged in literature. The informal largely subsidises formal and middle-class lifestyles. Very simply, if the three-wheel taxi drivers in Mumbai dwell in middle-class houses, they need middle-class incomes to live (i.e., reproduce their labour power). If so, the middle class may have to substantially downgrade their lifestyles to accommodate extra expenses and inconveniences. Self-built houses and informal economies enable the people ‘left over’ by the formal system to reproduce their lives by themselves at a lower cost, in houses built using leftover material on leftover spaces (in Wes Janz’s words). Looking down upon them is sheer ignorance and arrogance. Calling them squatters and their homes slums, is viciousness. This lays the background to police brutalities against entire communities in response to one crime and heavy-handed interventions into their environments by the state such as slum clearance.

What this approach hides is the resourcefulness of these people. A large proportion of the urban poor, especially in the non-West, house themselves, create jobs, plan settlements and do what the state and the market have failed to.

They enable the reproduction of the state and the market. The lead-planner of Gandhinagar, India, Prakash Apte, observed that Dharavi’s land use combination is a planner’s dream. It is also an economically successful place that provides employment for a large proportion of migrants who the Mumbai economy is unable to accommodate.

Yet the external lenses show a different picture, and push for renewal. Jane Jacobs was surprised when a Boston planner told her that the well-functioning North End would be subjected to urban renewal. She learned that planners are socialised to overlook their own instincts and social statistics and rely on professional norms. Such representations of human habitats imposing external knowledge are far more dangerous than the bulldozers that municipalities send. If they are to learn a little of the informal, it is imperative that the planners, architects and researchers unlearn much of their professional education – which some do – and re-world themselves in the ‘other worlds’ of the inhabitants.

There are continuing efforts in several Western cities to encourage aspects of urban informality: the farmers’ market is a classic case in point. At the same time, there are ongoing efforts in non-Western cities to add a semblance of order to the city. How do you see the ‘formal-informal’ binary from a global perspective?

When someone asked about farmers’ markets, a planning faculty proudly said: “We are not building farmers’ markets [per se] but use them to revitalise downtowns.” I see little understanding or respect among most planners, designers and their educators for informality and/or small-scale, grounded interventions, unless they fit within a larger, abstract model. The interest is largely in projects like business incubators that would spawn businesses for the larger system, but not farmers’ markets and small farms that might support these markets and provide more nutritious, relatable and sustainable food.

This large abstract thinking at the citywide and downtown scales is precisely the roadblock to empowering people to come out of their personal deprivations caused by deindustrialisation and urban decline in the USA.

For the cities to come out of their predicament, the emergences, especially those outside of formality, need to be acknowledged and enabled for they are the creative and transformative nodes with the potential for greater development. The pola in Sri Lanka, commonly known as a ‘periodic farmers’ market’, is an example. Nirmani Liyanage’s (2016) in-depth ethnography reveals that this is a modern institution adapted to contemporary conditions. The pola-vendors are not farmers (as they used to be) but sell in different close-by polas on different days of the week; neither does the produce come directly from the farmers, nor do all the vendors sell full time. Although it is hard to locate it within the formal and dismissed by many as informal, the pola is made up of an ingenious combination of formal and informal aspects. The market in Changsha, China, that Yuyi Wang studies also shows how the whole formal danwei (and its continuation) would have failed without the market.

Most designers and architects have a hard time engaging the informal city. They are not insensitive to it, but their very expertise in physical design often becomes their limitation. At the same time, leaving the city to unanticipated forces is also dangerous. What is the place of architects and urban designers when it comes to urban informality? Do they even have a role to play?

Architects are trained to help clients materialize their dreams through the formal market. They develop precise drawings of their design, select a builder through a bidding process and get it built through a building contract. Mainstream planners produce and legitimise abstract spaces for the state. People spend more energy familiarizing these into spaces they can use. The gap between the needs and provisions is evident in post-tsunami buildings, the Moken Village (Thailand), the Gypsy Village (Sri Lanka), in latter cases, providing (fixed) settlements for mobile people. Also, the formal cannot be separated from other spaces: the prime sector in Bhubaneswar (India) planned-city zoned for highest-level government officials has a self-built settlement in it. It is an ambivalent space: no one wants it, but no one wants to get rid of it. It is a highly unwanted space of highly wanted people who subsidise the highest levels of society.

In this sense, it is not dangerous, but important to leave room to familiarise provided space whether it’s a house or a city. Whether it’s the building of a ‘temporary’ kitchen by tsunami survivors to cook with firewood, the addition of a sunroom by an American middle-class dweller, or the establishment of a market closing a street, familiarisation is a part of living. This is also how new ideas, institutions and spaces emerge.

‘Unanticipated forces’ imply that we could anticipate all forces, but there is no science that could do this. It is through facing unanticipated forces that societies, communities and individuals grow.

There is no predesigned role in social design for architects to play. Yet there are select architects and planners across the world who have transcended these limitations. They are self-taught reflective practitioners who have learned by doing with the help of other professionals, disciplines and places. While leading architects such as Geoffrey Bawa, Charles Correa, Liu Thai Ker and Hasan Fathy have also learned from the locals, those like Antonio Ismail, Ted Cruz and Craig Wilkins have gone around the formal. They have trained themselves to work in the cracks, interstices and at the edges of the market and the formal.

Top Right: Pallet Houses Workshop with Nihal

Bottom Right: Nihal with former PM of Bhutan, Jigme Thinley

What are some great examples of cities that balance the formal and informal in conscious and creative ways?

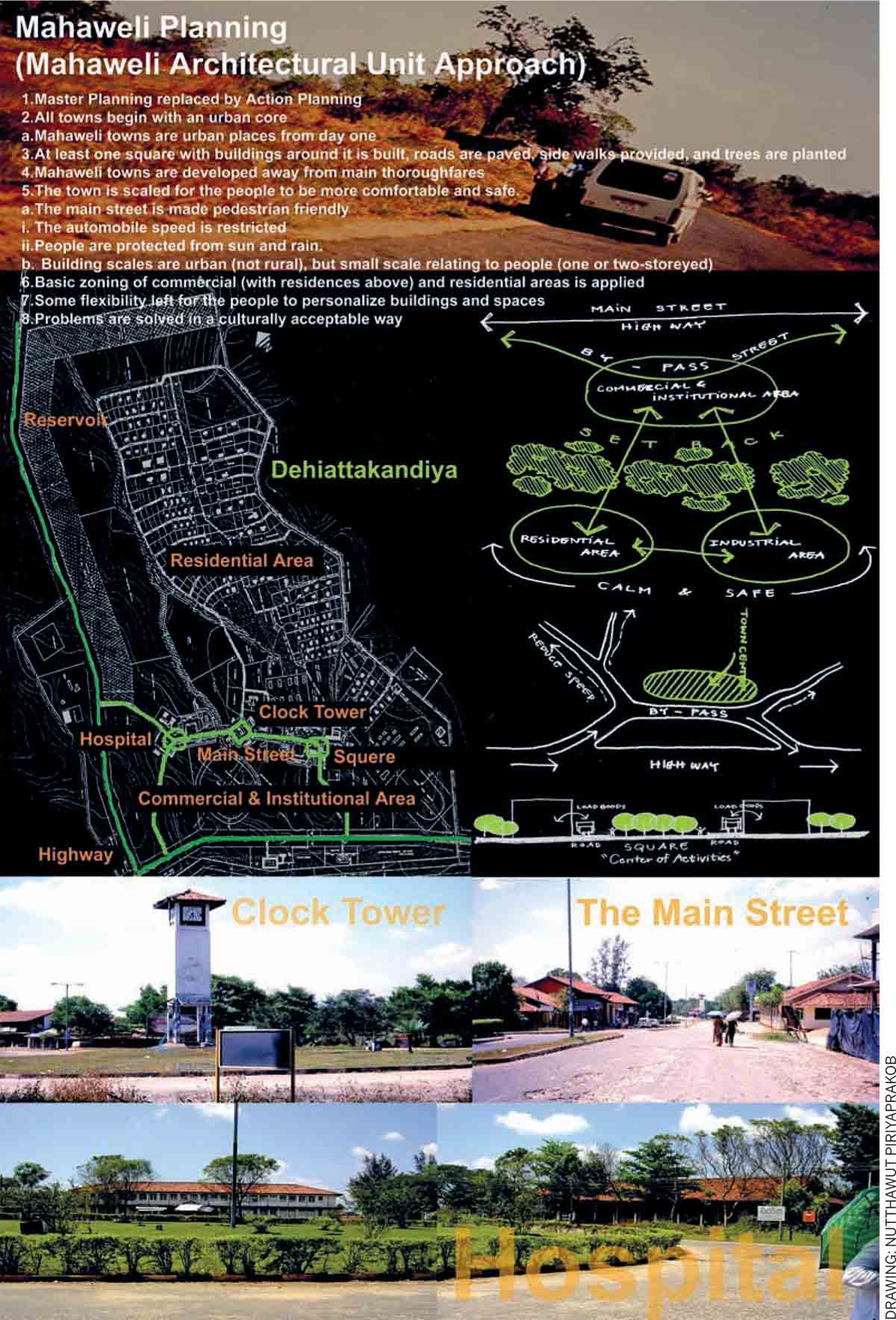

One of the highly successful projects that I have seen is the Million Houses Program (MHP, 1983-89) in Sri Lanka, particularly its urban component. The MHP is a political programme, but I refer to its core: the support system. Instead of providing houses, the programme opted to support the housing efforts of people ranging from upper classes who buy houses in the market to low-income groups self-building their homes. It not only accepts the complementarity between the so-called formal and informal, but also avoids providing one social group, offending or marginalizing the others. Although the social justice aspect could be further improved, the government also implicitly guaranteed not to involuntarily displace anyone, until the Rajapaksa regime (2005-2015) resorted to eviction in 2010.

This housing policy developed in Sri Lanka, expanded into the international arena and caused the UN to declare 1987 the International Year of Shelter for the Homeless (IYSH). In addition to influencing UN Habitat’s planning and development process, the idea of a support system is practised by organisations such as the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights in Bangkok, Thailand; the leaders claim that they learned it from Sri Lanka.

Another built project is the market in Citra Niaga, in Kalimantan East, Indonesia, designed by Antonio Ismail. It is a series of pavilions in an open field (concourse) with ample room between them to move around. The pavilions built in formal materials including concrete, are sub-dividable and the stores of various sizes are able to face outwards and inwards. Merging formal and informal, the outer ring that faces the street is a series of ‘formal’ stores. Ismail received the Aga-Khan Award for it.

Ordinary people indigenise, feminise, ruralise and modernise space, i.e. familiarise space so they can carry out their daily activities and cultural practices while at the same time adapting to the provided social and spatial environment. If people cannot live, both the people and the project fail; success depends on their ability to take ownership through familiarisation.

Comments (0)