As an urban designer, my interest is in creating public spaces in cities. You prefer photographing the way people use these spaces. What exactly are you looking for?

In 2011, I started a visual exploration of the consequences of growing population density. I selected nine fast growing megacities around the world that each hold 20 million inhabitants or would reach this number in the next couple of years. These cities grow at the rate of 50 new inhabitants an hour. How do people react to one another in areas of overpopulation? How do we define personal space in the public domain?

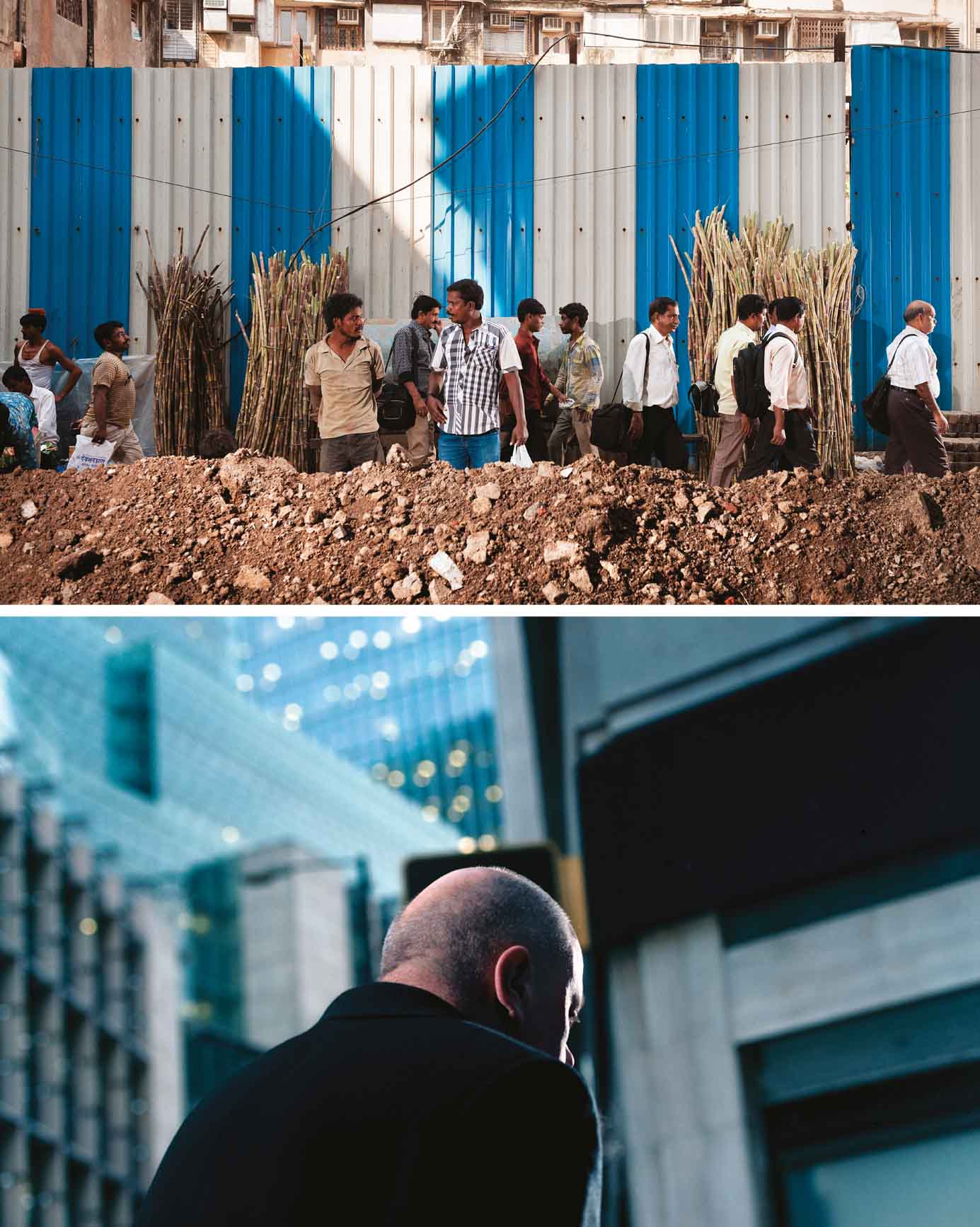

I observe street-life with a sociologist’s state of mind. I am drawn to little details in people’s behaviour, like small gestures, the position of the hands, the way people’s eyes are in search of one another or, on the contrary, try to avoid making eye contact. How do we present ourselves and what is it we try to hide from each other? What are the roles we play in our everyday lives and which masks do we don to perform them? To me, street life is a continuous stream of split-second urban encounters.

Street life is a continuous stream of split-second urban encounters

When you photograph users in the public domain in busy cities, how do you register the anonymity of each person in the crowd?

The anonymity of the man in the crowd is an important part of the metropolitan experience. There are unwritten social rules that provide everyone with a certain space and freedom, if we leave each other alone. Within certain boundaries, you can watch and observe something in public that is private. We are alone in a crowd, in the company of strangers.

In urban life, there is an interesting paradox at play. Though we desire to belong to a group, we avoid contact with that group. Engagement with strangers rarely happens because of the challenges and insecurities that come with it; we could get hurt or disappointed, or we might get involved in a long conversation that we do not have time for. We need the group but we like to remain an individual as well. Therefore, often the stranger remains unknown and we are left being alone together.

How do people manage to be alone in these public spaces?

I believe that overstimulation of modern city life makes us detach from space and reality. In a sense, we all get increasingly alienated from social interaction in the streets. While commuting, we use many tools to avoid people, like eating, reading or sleeping. Nowadays we can email, text, Skype, play games, watch films, shoot photos, edit, publish and send them. With the smartphone, we have brought the office into the streets. The most performed and popular act is the one of pretending to be busy. Plus, we have many screens to hide ourselves behind, like sunglasses, earplugs and telephones. Whenever we are in an uncomfortable environment, we grab these devices to hide our awkwardness, dramatically decreasing the chance of interacting with individuals outside our social group.

As a photographer, I was trained in the studio and later got interested in urban photography. I’ve started to combine these genres and bring the studio lights to the streets. I began to imagine the city as a huge studio and its citizens as actors. As I approached the street as a stage, it made me wonder if our lives are performances. I started to read about the performativity theory. For example, sociologist Erving Goffman has written about the presentation of self in everyday life. It seems, in daily life, we are performing social roles and we wear the appropriate mask. While commuting in the city, we drop this mask and replace it with another one, the mask of ‘self-protection’. I am interested in this mask, because I believe it provides us a lot of information about the self and the construction of identity.

Though we desire to belong to a group, we avoid contact with that group

Do you use any special techniques to photograph these public spaces?

I have a background in cinema where I learned some exquisite lighting techniques. I consider my work to be documentary-photography combined with cinematic light. I position my flashlights on the street, creating a designated zone where the protagonists walk into my range of focus and exposure. The lights enable me to freeze movement. The images suggest off-screen events since they are more about what is outside than inside the frame. They make you wonder what just happened or is going to happen. They are frozen moments that feel unreal or, as I like to consider them, hyper-real.

I position artificial lights on the street to create heightened drama. With this, I invite the spectator to carefully examine the image he is confronted with. The result: we become aware of details in faces that remain unseen at the ‘speed of life’. Now we can read the state of mind of city dwellers. I am not particularly in search of states of alienation or isolation; it is about what I find when photographing people who are unaware of what I’m doing.

Next to the light, I am drawn to the use of fast shutter speeds: the unique quality of photography to arrest movement. I try to capture offbeat moments. I like the images to appear as film stills out of a non-linear urban continuum. I intend to slow people down and make them think about the meaning of inhabiting the new reality of fast growing cities.

Bottom Left: New York, 2011, Bottom Right: Lagos, 2016

You have photographed busy citizens in metropolises on different continents – New York, Sao Paolo, Seoul, Mumbai, Hong Kong, London, Lagos, Istanbul and Mexico City – and aim to finish the project next year. How do you capture the sense of place of these cities in the photographs you make?

The cities I photograph are ‘on the move’ and its inhabitants are in transit. This in-between-ness is representative of the present urban state of mind of the unfocussed attention of city dwellers. Metropolitan life over-stimulates our senses to which we react with indifference and blasé attitudes. With the help of telephones, headphones and sunglasses, we become oblivious of our surroundings.

The cities I photograph are ‘on the move’ and its inhabitants are in transit

The subject matter of this body of work is not the city, but city-life. Based on Marc Augé’s theory of ‘Non-Places’, my work is more about city ‘space’ than ‘place’. I position myself in places of ephemerality and liminality. The series represents a wandering stroll in an imaginary city of the future.

Can you give examples of how people in different cities reacted to your role as a photographer?

For me, city life is a visual spectacle. I want other people to enjoy this work as much I do. I am fascinated by the social and cultural differences of all the cities I have worked in. However, for this project, I haven’t tried to capture the differences, but rather the similarities between the people. Biologically we are amazingly alike and that is something I find very reassuring.

The speed of urban life is so intense that I never have the time to talk to people passing by. And besides, I don’t like my presence as a photographer influencing the subject. You can tell when people are aware of being watched. After installing my lights, as soon as I look into the viewfinder, I become a fly on the wall. Sometimes I even forget that I am there. It is a disembodiment almost, the closest you can get to non-existence.

Because of globalisation, megacities today are more alike all over the world. The effects of mass media on human behaviour are universal. This is especially notable among the younger generations, who eat the same food, wear the same clothes, listen to the same music and watch the same films. Rem Koolhaas wrote an inspiring and provocative essay on the future of cities in The Generic City.

In general, I can say that there is a universal suspicion towards photographers. Sometimes this is fed by political instability, like in Istanbul, where I worked very recently. In most cities, I had some encounters with the police and private security officers. Yet the people I photograph have always been gentle and interested in what I am doing and are happy to be photographed. I always end up with a list of email addresses of the people who want copies of their photographs.

After installing my lights, as soon as I look into the viewfinder, I become a fly on the wall

Can you name three public places in cities you photographed where, despite the busy nature of these cities, the citizens seemed to be in harmony with their urban context? Why do you think they were at ease in their context?

Lagos/Nigeria: Lagos Island

Lagos is maybe the most difficult city I have ever worked in but, at the same time, the most rewarding. It’s one of the fastest growing capitals on the African continent and may well become the third biggest city in the world by 2050. Yet there’s so much that remains unknown about it. Community structures are based on the indigenous culture of tribes. Lagosians are very communicative and socially engaged; on the street, everybody seems to know one another. Feelings of pride and respect are evident and therefore you must acknowledge each other by making eye contact.

Although the population density here is one of the highest I have ever documented, people surprisingly seem at ease with each other. Due to the proximity to other people, there is a lot of bonding and human contact.

London/England: Shoreditch

London is the most ‘international’ city I have worked in. Its city centre is truly a mix of ethnicities from all over the world. Shoreditch, where I lived for a year, is very busy, yet never crowded. The renovation of old industrial warehouses into offices or residences created an eclectic mix of architecture. The area is situated next to the ‘city’ of London and the ‘Bank’ district where I have shot many of my favourite images. The price of real estate here, per square metre, is one of the highest in the world. Close to the Brick Lane area people seem at ease. Although the place is highly gentrified, people can be whoever they want.

Mumbai/India: Mohammed Ali Road

My favourite street to photograph in Mumbai is Mohammed Ali Road, where there is beautiful sunlight hitting the dusty street life under the JJ Flyover. I spent many days walking this prominent street with its bustling traffic. This area is full of life because of the marketplaces surrounding it. The first time I saw it I was amazed by the sweaty men that transport goods every day. The street is also the threshold of two neighbourhoods with different religious backgrounds. It is a meeting place of different people where they have a humble tolerance and interest in each other.

I lived in Mumbai for a month, always considering myself an outsider to its culture, but at this street, despite the incredible crowds, I found a unique sort of harmony and peacefulness. Compared to London, where I believe society functions as along as people have money, here in Mumbai, people seem to engage in a contemplative, alost spiritual way with one another, something that I find very hopeful and beautiful.

From my experience in working in all these highly populated cities, I can conclude that population density does not have to stand in the way of human happiness. I will argue that harmony and feelings of happiness in everyday life can be found especially in a dense, compact city. I believe the modern megacity creates lots of issues yet, at the same time it can be the solution to its own problems.

Comments (0)