A history around water

The Dutch are familiar with water and aware of its qualities and strength. And they’ve been in a constant struggle to curb and control water.

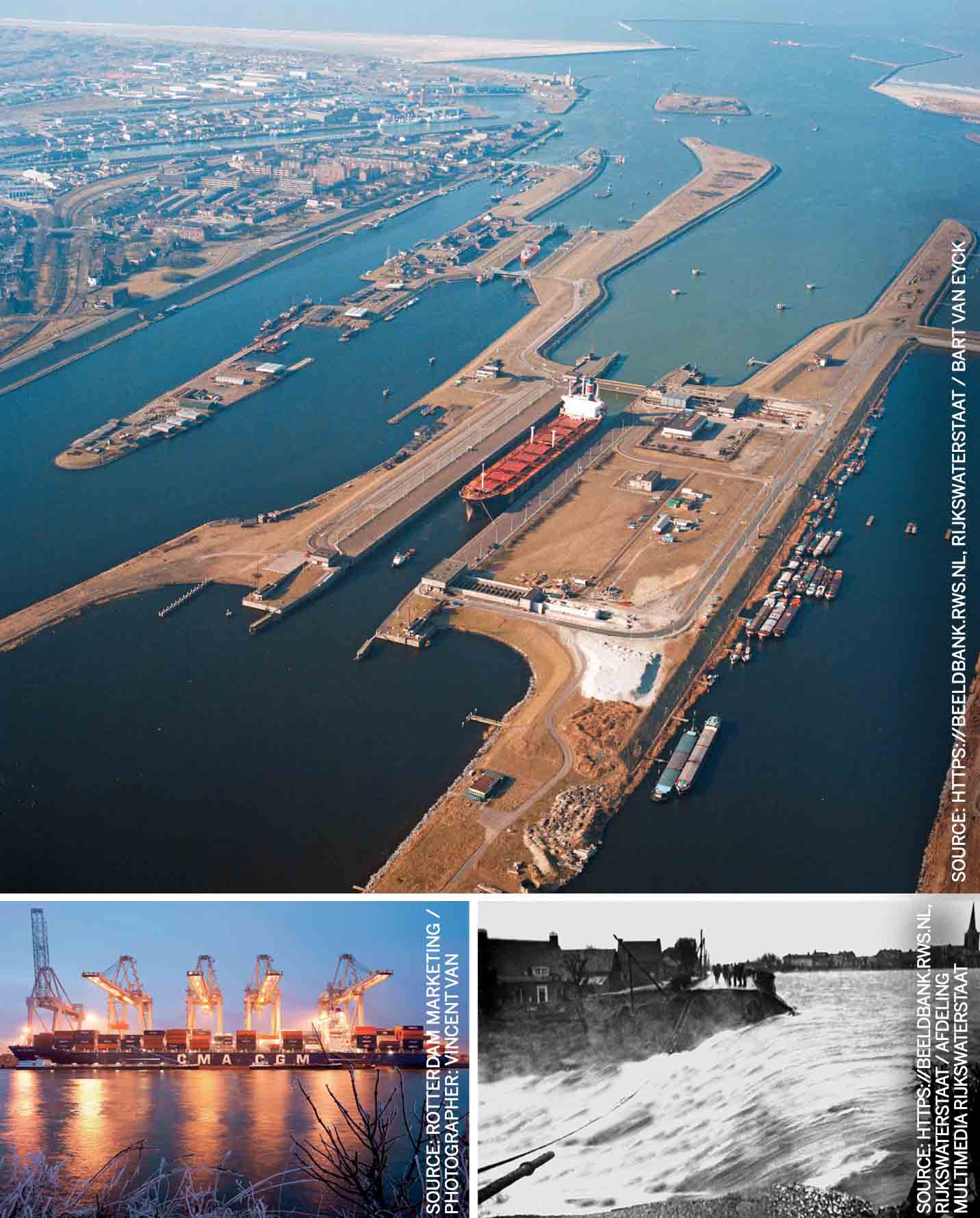

As a sailing nation, the Netherlands has known wealth and success thanks to water. The location of the first settlements along the major rivers, such as the Rhine, the Meuse and the Scheldt, led to the creation of storage and transhipment sites and resulted in commercial ports. In the Golden Age, large trading cities were created along the coast, Amsterdam being the most famous of them. In the 19th century, Rotterdam came up as a trading port and became the world’s largest port of the time.

To optimise the network of waterways, a large number of channels, canals and river sections were dug over the centuries. Today, the Netherlands has 8,000 kms of navigable water. There are more than 5,000 kms of waterways; of which 4,800 kms are suitable for freight and 1,200 km have been formed by rivers. In 2015, 125 million tons of bulk cargo and containers were transported over inland waterways.

The Netherlands is also aware about the negative impact of water. People still remember the dramatic flood of January 1953. Within a few hours, 165,000 hectares of land flooded and 475 kms of dikes were severely damaged or broken, leaving 1,835 people dead and drowning tens of thousands of animals.

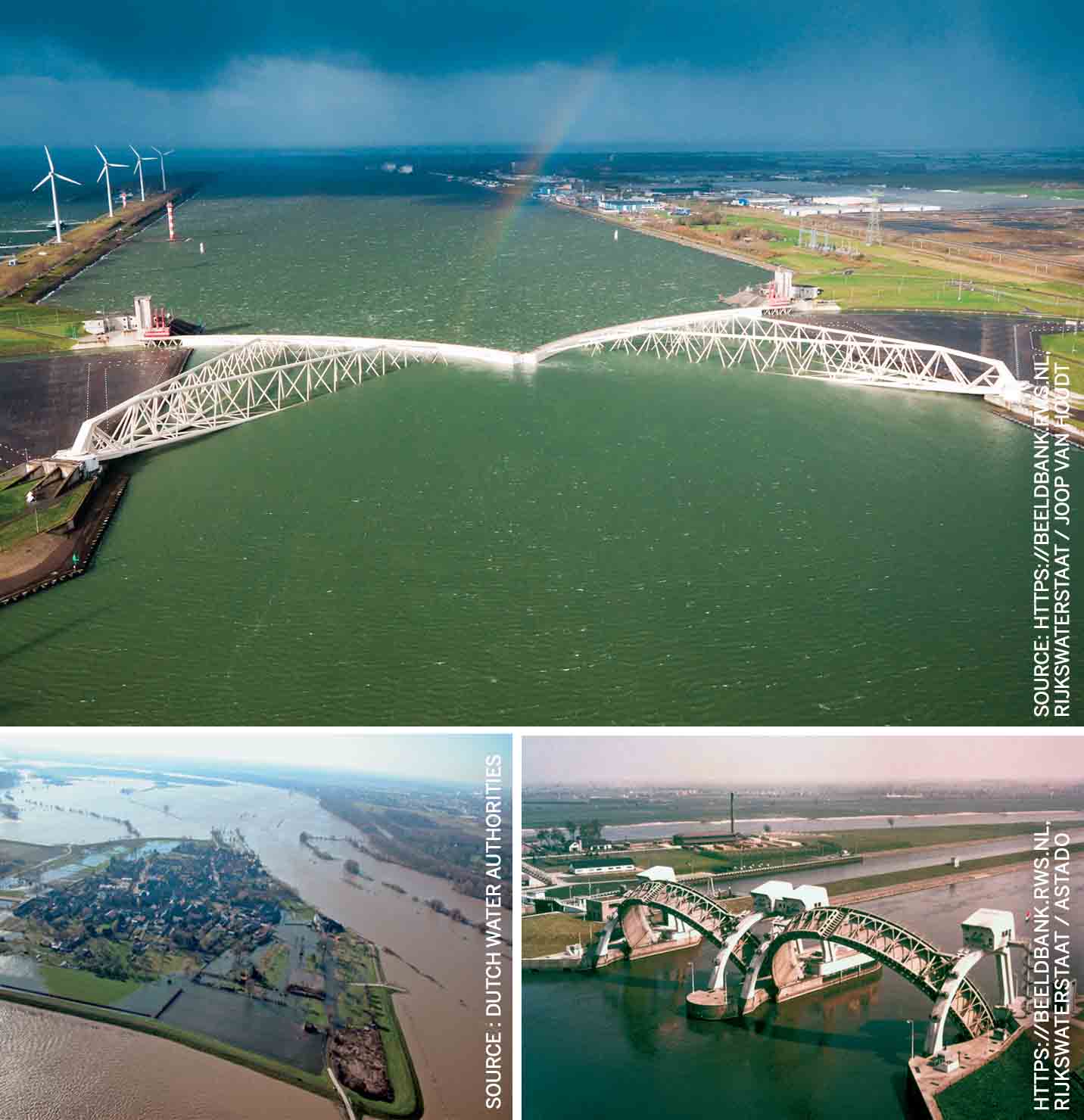

After this disaster, the Netherlands decided to create a global water management organisation, the Delta Plan, in which some of their most ingenious technical knowledge was tested. The Dutch people understood that such a system, capable of monitoring and controlling all the levels of the water network was vital; both in terms of quality and quantity of water, to keep navigable rivers and canals clean and to ensure safe water levels inland for the well-being of people and animals.

Below Left: Container ship in the Port of Rotterdam. This is the largest port and industrial complex in Europe with a total cargo traffic of 430 million tons in 2010

Below Right: Breach in the dike at Ouderkerk aan de IJssel

Water Management Organisation

In a low-lying landscape as in the Netherlands, keeping the land dry and assuring flood prevention have always been essential to keep the country liveable. But with global warming, the sea level rising and the decreasing soil in the polders, things are getting complicated. Moreover, extreme rainfall resulting in acute flooding has recently become unusually common in the Netherlands.

Because water management matters affect all Dutch people, this specific field requires a central coordination and some master planning, where various factors would be taken into consideration. This includes the economic necessity for safe vessel traffic on water and the need to protect and improve the living environment in towns and rural areas. Maintaining and managing (also financially) are paramount, but at the same time looking for opportunities to meet new needs, for example due to climate change, are also imperative.

The Netherlands decided to create a global water management organisation, the Delta Plan, in which some of their most ingenious technical knowledge was tested

The control of water in the Netherlands is a government job. It is defined in the Water Laws: the ‘Waterschapwet’ (1992). All the residents of the Netherlands need water care and have the right to express their opinion about it because they pay taxes for this water control. Water projects serve a common interest and therefore they are financially feasible.

The Water Laws are applied within four authority organisations: the national government, the provinces, the Dutch Water Authorities and the municipalities. Within the principles of decentralisation and autonomy, all authorities have democratically-elected representatives and their own set of responsibilities.

At the national and regional level water is controlled by ‘Rijkswaterstaat’ (RWS), an independent arm of the Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment, and by the Dutch Water Authorities.

• The National Government

The Central Government is responsible for national policies and measures to protect the land from the sea and the major rivers. Decisions go through the Ministry of Infrastructure and Environment. The government policy is described in the National Water Plan 2016-2021.

Commissioned by the Ministry, Rijkswaterstaat, with approximately 9,000 employees, manages and develops national primary road works, main waterway networks and main water systems. It warns of possible calamities, ensures the construction of dikes and maintains the coastal zone. Within the regional services of Rijkswaterstaat, existing structures (dams, weirs and storm surge barriers) are kept in good condition and new construction projects are prepared and implemented.

Since 2012, there is an independently operating Rijkswaterstaat Traffic and Water Management body.

• Provinces

The National Policy is applied by the provinces in each region. The Soil Protection Act states that the management of groundwater needs to be managed by the province.

Decisions to initiate public projects in a polder or a municipality must be approved by the ‘College van Gedeputeerde Staten’, the Provincial Executive Board. Hence the technical services of the Provinces act as advisers.

Below Left: Flooding along the Maas River

Below Right: Weir in the Lek River near Hagestein. When the weir is lowered, the concave side of the arc is targeted to the high water level

• Dutch Water Authorities

Dutch Water Authorities is an international organisation comprising 22 regional water authorities in the Netherlands and their umbrella association, the Unie van Waterschappen. The regional water authorities have democratically elected boards. Dutch Water Authorities promotes the interests of the regional water authorities at the national and the international levels and shares a European office in Brussels with Vewin, the Dutch association of drinking water companies.

In the Netherlands, the Dutch water authorities take care of the maintenance of regional dams, dikes and embankments, and sometimes of roads. When needed, channels and polder canals are widened and pumping stations built.

Besides, Dutch Water Authorities controls the water level in the polders thanks to a complex system of water storage basins, locks and pumping stations. Often, far below sea level, the water level inland is thus properly maintained. By closing weirs, the water level and therefore the navigable depth can be determined according to needs.

By drawing up plans, Dutch Water Authorities also ensures the quality of water and looks to its improvement. To manage ground and surface water, there are several water discharge and water intake areas. The locks guarantee that the least possible fresh water flows into the North Sea.

Water management involves much more than building dikes and windmills

• Municipalities

The municipality is responsible for water engineering activities within its jurisdiction as well as related aspects like formulating expansion plans.

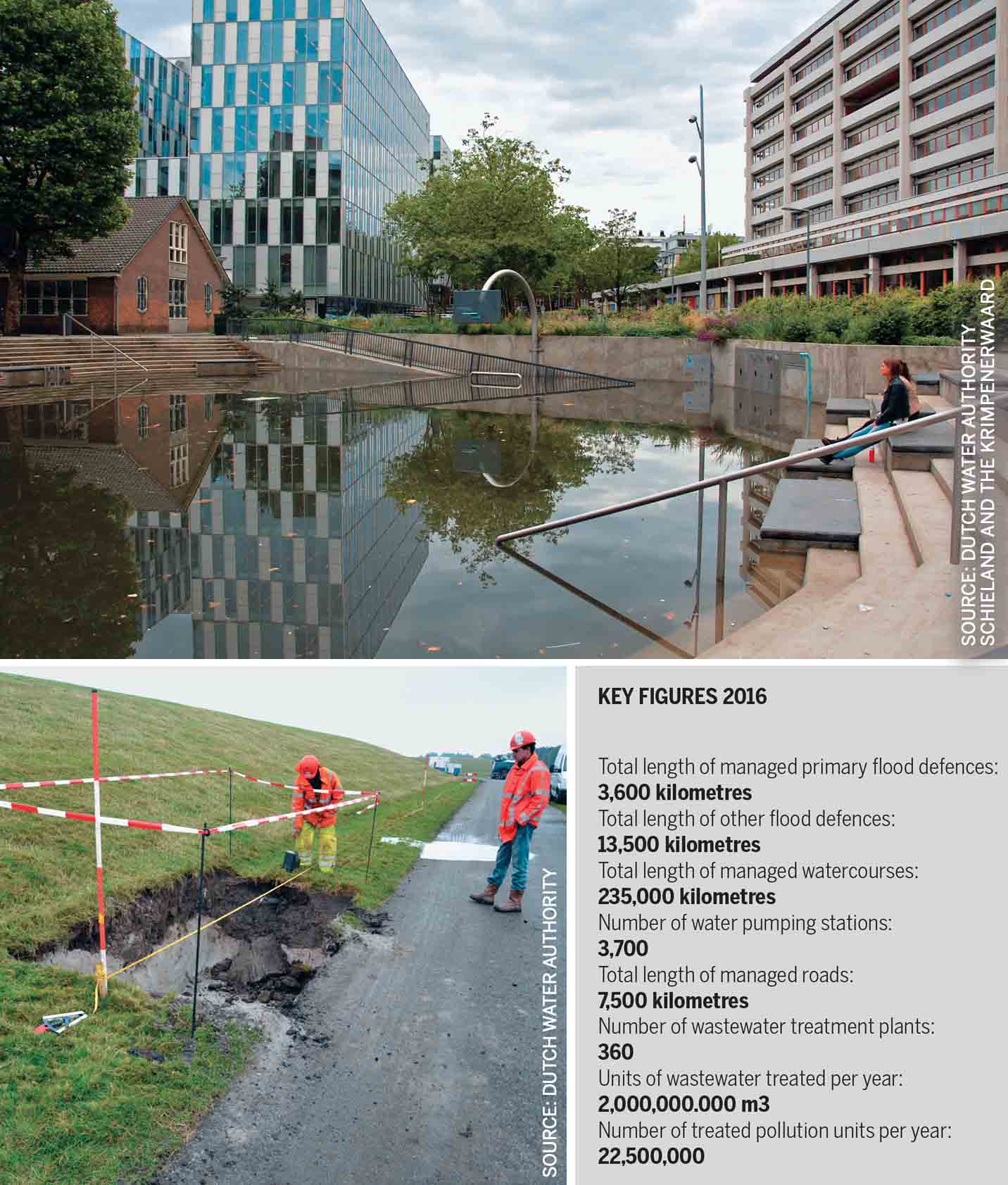

In the urban area, the municipality is responsible for the quality of ground water and the transport of sewage or rainwater to the sewage system. Also, rainwater harvesting is one of the responsibilities of the municipality. By creating inventive underground water storage or designing public water squares, the maximum amount of rainwater can be accumulated.

Within the organisation of the College of Mayor and Aldermen (B & W), one alderman of the Physical Planning and Public Works (Territory Affairs) is responsible for the implementation of these projects.

Innovation

Examples of innovation in the Netherlands are:

• Projects that encourage water safety

Geotextile for the prevention of piping is an example of such an innovation.

The experiments with dike monitoring with sensors also serve this purpose. The ‘Livedijken’ Project provides essential information for the inspection of dikes during periods of high water levels. This information can also be used for improving designs and testing of dikes, as well as for daily control and maintenance.

In the forthcoming years, the system will be further developed together with Dutch Water Authorities, private companies and knowledge institutes and will be applied at a number of locations. Continued development: 2014-2016

• Projects that respond to developments in the availability of freshwater

The so-called backshore concept at Andijk combines improvements of water safety with the storage of excessive freshwater for later use.

Besides, to stimulate innovation in the Netherlands, Dutch Water Authorities organises the Water Innovation Awards every year.

The Water Spare System by Acacia Water Organisation is one of those new ideas exploring that theme. A freshwater system provides sufficient water for agricultural purposes, reduces the outflow of nutrients and pesticides and provides safe water without harmful germs like Brown rot (Ralstonia solanacearum) and Erwinia die during soil passage. Rainwater on the parcel is collected through drainage pipes, stored underground and is available for irrigation through drip hoses. Ongoing pilot projects have demonstrated that it is possible to save on underground sweet drain water with the aim to extract it later and therefore become self-sufficient. Benefits such as reduced nutrient leaching, reducing the burden of disease and additional harvest by precision-agriculture contribute to the short-term feasibility, both technically and financially.

• Projects that contribute to the water quality

An example of such a project is the Pharmafilter, which ensures that medicinal residues and hormone-disrupting substances from hospitals are filtered before being discharged as waste water.

Below: Sensors being placed in the dike

• Projects that ensure climate-resistant cities

In Rotterdam, there’s a playground that also functions as temporary water storage for excessive rain water.

Since 2014, the government and local authorities are working together to realise regional ambitions for a sustainable Afsluitdijk (barrier dam). Energy is being produced from several techniques: osmotic power (Blue Energy pilot plan), tidal energy, wind energy in the long-term and solar energy. The region also has plans for an innovative fish migration river.

By creating inventive underground water storage or designing public water squares, lots of rainwater can be accumulated

International influence

Because of its history with water and its knowledge about water, the Netherlands is an international leader when it comes to the control and management of water, nowadays called ‘water management’. Water management involves much more than building dikes and windmills. The work also entails water level management, water quality management, adapting to climate change, dredging and wastewater treatment.

The Netherlands has huge expertise in this field and provides specialists for water projects around the world. After the flood devastation by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, Dutch Water Authorities shared their knowledge to improve dikes in Louisiana, USA.

Dutch Water Authorities promote these interests at the national and international levels. It is the point of contact for expertise in regional water management. It can provide answers to a wide range of questions and requests about good governance, innovation and trade.

Dutch Water Authorities can:

- Offer expertise in regional water management and water governance through joint projects, expert capacity, field visits and presentations.

- Deal with specific requests for international cooperation in one of the nine focal countries: Bangladesh, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Romania, Vietnam and South Africa.

- Respond to requests for international cooperation from Dutch businesses.

- Provide assistance before, during and after water-related disasters.

The Dutch Water Authorities projects are open for visits from international delegations.

Comments (0)