A recent American Automobile Association study revealed that 63% of walking or cycling adults in the U.S. would not feel as safe sharing the road with a self-driving vehicle. It’s an understandable concern. With increasing advances into the automated world, people are beginning to express and feel the strain of change.

The fear associated with accepting driverless vehicles en masse – technophobia – is not only an expected part of progress but also a significant hindrance. How might we help people accept a new reality where human beings give up control to robots? Jaguar Land Rover thinks the answer may be in humanising technology: in a recent Future Mobility Research project, self-driving pods were fitted with ‘eyes’ that acknowledge and respond to nearby pedestrians. Will such interventions be necessary in building confidence and adoption in the face of behaviour change?

Change seems impending in almost every major future domain of long-distance mobility today, with electric vehicles, smart cars, ride sharing and declining ownership.

While people once associated pride in being able to afford and buy a car, sharing a vehicle with the larger community no longer has the glamour of ownership. Managing an electric vehicle relative to a gasoline car brings a new set of limitations and imagining an autonomous car with no steering wheel at all is a big shift from how cars have been perceived for several decades.

There are even bigger disruptions awaiting users: global innovation consulting firm IDEO forecasts a future of ‘moving spaces’, with inverse commutes where working spaces will come closer to where people live. These ‘work on wheels’ pods can be designed for small teams to collaborate on the go and can be parked at any location relevant to the day’s work.

With such fundamental shifts expected in our day, lifestyle and behaviour, how can users be coached to cope with change? Should design teams – those that build new products, services, and experiences – include training as part of the offering?

Picking up protocols of new behaviours may be critical, but equally important is the acknowledgement of the frustration, confusion and awkwardness associated with the change. How might a designer’s process evolve to adapt to these requirements?

The human-centered design thinking methodology has proven to accommodate users’ needs through empathy and contextual research. In 2016, Benoit Colin, a global automotive and New Mobility manager at Nissan collaborated with the World Resources Institute on improving the commute experience using design thinking.

He found that social validation is key to adoption of any new mode of transport; without a positive perception from their community, users are not likely to adopt a new mobility service or product.

They need to see solutions in action and learn how they can be adapted to individual interests and preferences.

So how might the design process have in- built allowances for early adoption education and awareness? Including this change management function into the early stages of research and design could potentially avoid lackluster launches and product failures. By engaging a set of potential users from the beginning – as increasingly happens with projects backed on Kickstarter and Indiegogo – the feeling of ownership would emerge, creating excitement and buzz.

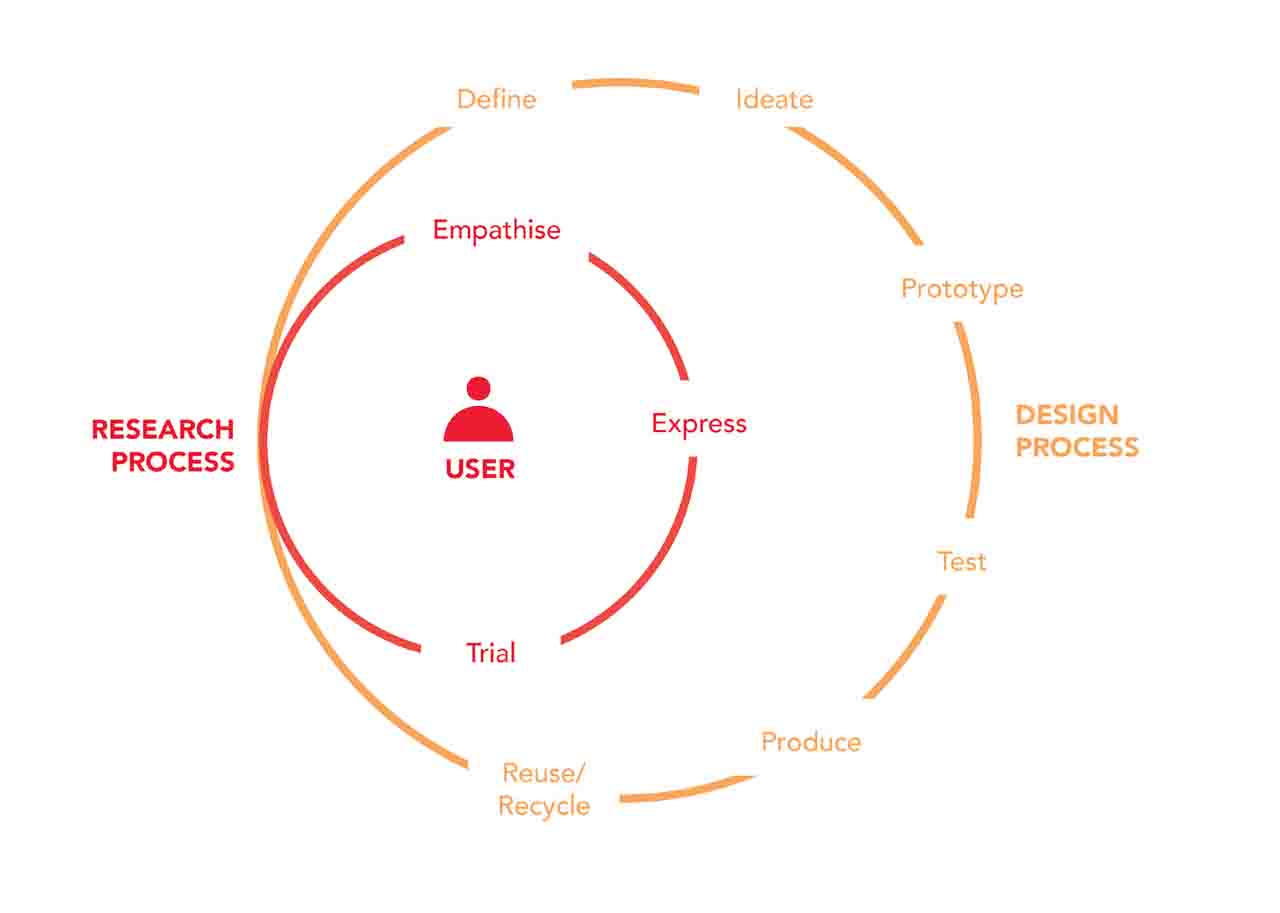

There are several ways to have potential users participate in the research and design process, mostly falling into three buckets: empathise, express and trial. ‘Empathise’ has been a well-established form of primary research: immersing into a user’s context to observe how they behave and feel.

‘Express’ can be a new form of research methodology that allows for potential users to vocalise their fears or concerns with adopting a new product, service or system. It is an opportunity for them to be heard and for designers to identify expected changes in their lifestyle. With this knowledge early on in the process, design can address challenges or opportunities on an adoption journey.

CREDIT: IDEO |  CREDIT: IDEO |

‘Trial’ is an extended form of testing, where a set of users would live with and use a series of prototypes throughout the design process, contributing to insights relating to managing change. Conducting research cycles with these three methods would result in a holistic value proposition for users.

Maybe it is time for large companies to adopt a more human approach to their market, allowing users to be a part of their inside process. While there is a risk of appearing vulnerable, it will only make them more relatable to the people ultimately paying for their offerings.

Comments (0)