PHOTOGRAPHS COURTESY: VINCENT CALLEBAUT ARCHITECTURES, BELGIUM

“Nature in the city must be cultivated rather than ignored or subdued.” – A.W. Sprin, The Granite Garden: Urban Nature and Human Design, 1984

Cities need to be looked at as ecosystems of natural environments rather than as machines inserted into the natural environment. The Urban Ecology, Eco-city Conference 1990 Report (Berkeley), through its mission statement has stated 10 principles for envisioning cities as ecosystems:

• Revise land-use priorities to create compact, diverse, green, safe, pleasant and vital mixed-use communities near transit nodes and other transportation facilities.

• Revise transportation priorities to favour foot, bicycle, cart and transit over automobiles and to emphasise ‘access by proximity’.

• Restore damaged urban environments, especially creeks, shorelines, ridgelines and wetlands.

• Create decent, affordable, safe, convenient, racially and economically mixed housing.

• Nurture social justice and create improved opportunities for women, people of colour and the disabled.

• Support local agriculture, urban greening projects and community gardening.

• Promote recycling, innovative technology and resource conservation while reducing pollution and hazardous wastes.

• Work with businesses to support ecologically sound economic activity while discouraging pollution, waste and the use and production of hazardous materials.

• Promote voluntary simplicity and discourage excessive consumption of material goods.

• Increase awareness of the local environment and bioregion through activist and educational projects that increase public awareness of ecological sustainability issues.

Human activities also partly determine ecosystem structure and function. The architecture becomes metabolic and creative. The facades become intelligent and regenerative, like an organic epidermis. The roofs become the new grounds of the green city. The garden is no more placed side by-side next to the building; it is the building. The architecture becomes cultivable and nutritive.

Vincent Callebaut Architectures in their sensitive response to eco-systems believe buildings to be a part of the natural systems themselves. Through their projects they attempt to respond with buildings and the urban fabric as an extension to the existing ecosystem.

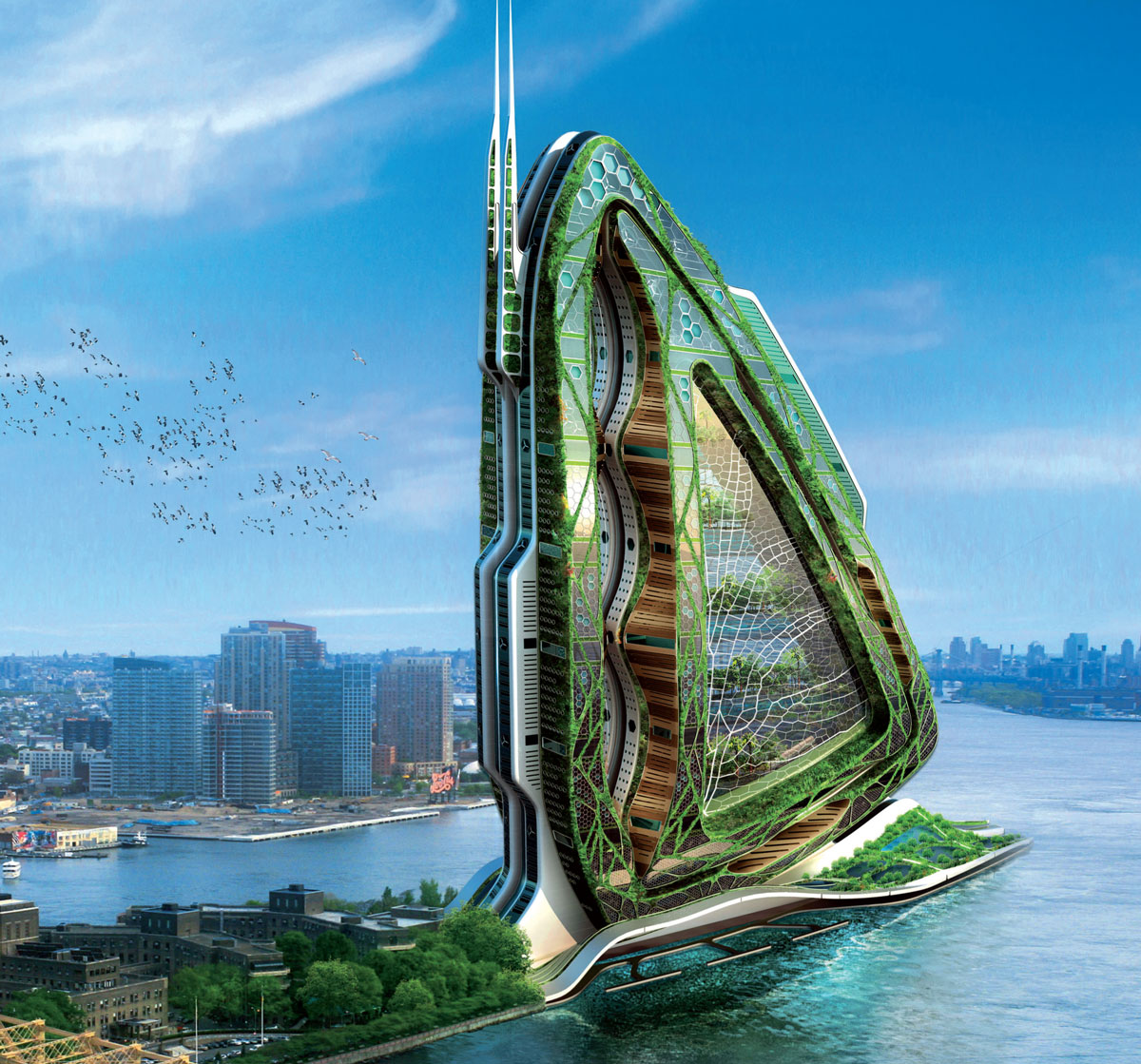

DRAGONFLY: A NOURISHING, VERTICALLY CULTIVATED CENTRAL PARK (New York City, 2009)

The Dragonfly project suggests a prototype of an urban farm around a mixed programme of housing, offices and laboratories (in ecological engineering), farming spaces, which are vertically laid out on several floors and partly cultivated by its own inhabitants. This vertical farm sets up all the sustainable applications in organic agriculture based on intensive production, varied according to the rhythm of the seasons. Furthermore, this nourishing agriculture is in favour of the reuse of biodegradable waste and the harnessing of energy and renewable resources for planning eco systemic densification.

In order to conceptualise this project and give a point of view in the ecological and social crisis debates, Dragonfly is set up along the East River at the South edge of Roosevelt Island in New York between Manhattan Island and Queens district.

So as to challenge the land pressure, Dragonfly stretches itself vertically in the shape of a bionic tower, relocating a new urban biotope for the fauna and the local flora and recreating a food production auto-managed by the inhabitants in the heart of the Big Apple.

Floor by floor, the tower superposes not only stock farming ensuring the production of meat, milk, poultry and eggs but also farming grounds; true biological reactors continuously regenerated with organic humus. It diversifies the cultivated varieties to avoid the washing of soft substratum. Thus, the cultures succeed one another vertically according to their agronomical ability to provide some elements of the ground, between the essences that are sowed and harvested. The tower, a true living organism, becomes thus metabolic and self-sufficient in water, energy and bio-fertilising. Nothing is lost; everything is recyclable to a continuous auto-feeding!

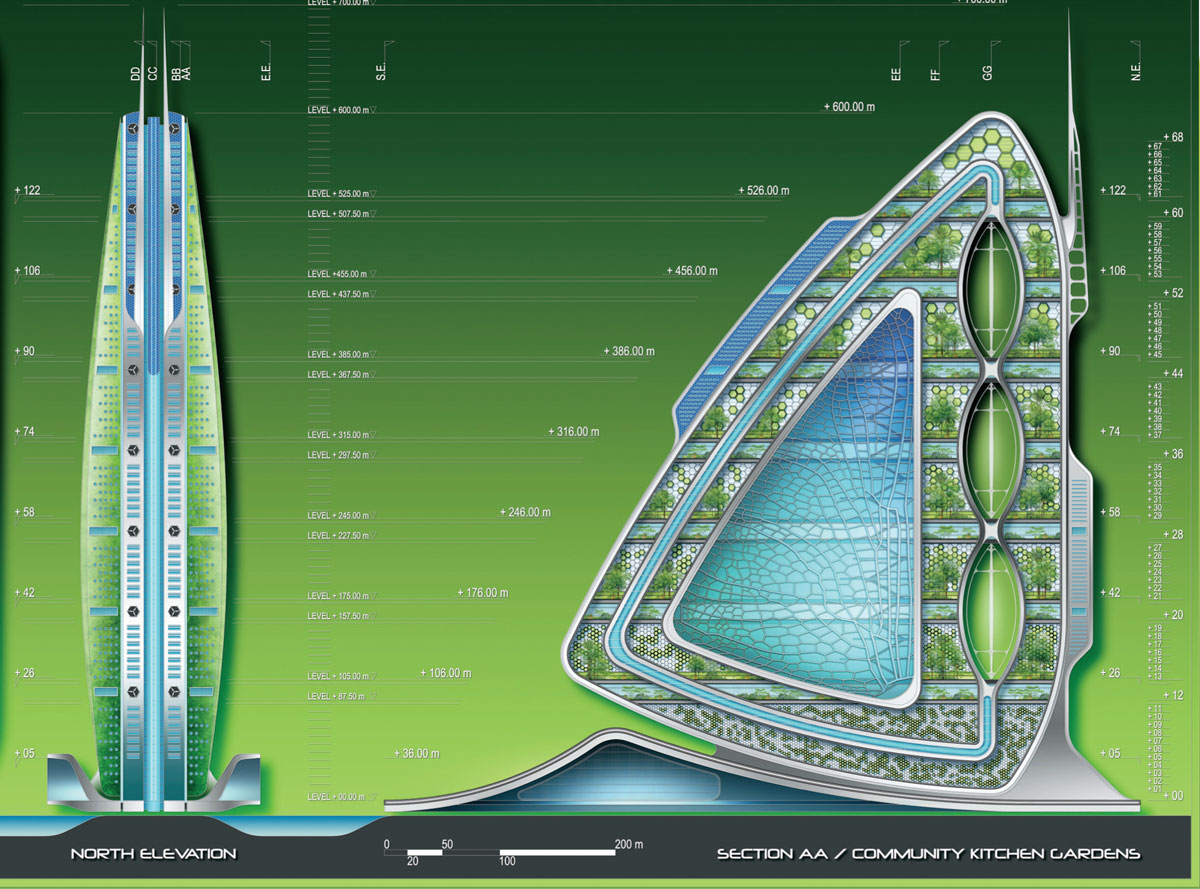

A bionic and energetically self-sufficient architecture

The architecture of Dragonfly prototype suggests reinventing the vertical building (that outlined the urban boom of New York City since the 19th Century) as structurally and functionally as also ecologically and energetically.

To ensure the social diversity and a permanent life cycle (24X7) in the tower, the mixed programme is mainly laid out around two functional poles of housing and work place. Housing is combined with offices, research laboratories; the agricultural and leisure spaces are combined with gardens, kitchen gardens, orchards, meadows, rice fields, farms and suspended fields. Optimal movement of people and products is achieved through a looped circulation using numerous elevators and stair wells. This mode of distribution serves all the levels for both the input and the recycled output from plants, animals and human beings.

The design of Dragonfly integrates renewable energies to meet the needs of a completely energetically self-sufficient project in the urban centre. Actually, the South prow of the tower has, in all the heights of its curve, a solar shield. This produces half of the electric energy needed for its functioning. The three wind machines ensure the other half. The vertical axes of Darrieus type coils itself up in the three lenses hollowed in the North part of the micro-pearled shell towards the dominant wind of New York.

The exterior facades of the tower present a double personality. Actually, in the West of the Island, near Manhattan, the facades are treated with planted walls, whereas in the East near the Queens district, the wet exterior walls are cultivated with tropical essences. These vertical gardens enable the filter of rain water and the effluents of domestic liquid waste of the tower inhabitants. The collected waters undergo an appropriate organic treatment for reuse in farming, bringing all the nitrogen and an important part of phosphorus as well as potassium needed for the production of fruits, vegetables and cereals.

Outlining the bank of the Roosevelt Island, the tower widens at each side of its bases to better integrate the flows that cross it and to welcome two marinas along the East River. This widening out forms two huge photovoltaic vaults such as a solar dress floating above these two urban harbours: on the western marina side, the wooden pontoons of the taxi boats open panoramically on the Midtown bank and on the eastern marina side, the floating market oriented towards the Queens district is designed to distribute through the river the food production of this vertical farm to the heart of Manhattan and to its million and a half city residents.

Moreover, these two marinas accommodate two huge aquaculture ponds, true tank of soft water filtered by the planted frontages and dedicated to be reinjected in the hydroponic network of the Dragonfly tower. The Dragonfly project challenges the city of New York to rethink its food production. In response, this project of an inhabited vertical farm responds to the contemporary dilemma of producing not only ecologically but also more intensively on non-extensive earth, by merging directly the production place and consumption place in the heart of the city.

ASIAN CAIRNS, TOWARDS A NEW MODEL OF SMART CITY (2013, Shenzhen, China)

Benefiting from its privileged geographical position in the heart of the Chinese megalopolis of the Delta of the Pearl River, Shenzhen faces spectacular economic and demographic development. The Asian Cairns project fights for the construction of an urban multifunctional, multicultural and ecological pole. It is a prototype of a green, dense, smart city eco-designed from biotechnologies.

Three interlaced eco-spirals

The master plan is designed under the shape of three interlaced spirals that represent the three elements: fire, earth and water, all organised around air in the middle. Each spiral curls up around two megalithic towers and forms urban ecosystems implanting the biodiversity into the heart of the city under the shape of vast public orchards and urban agriculture fields. Huge basins of viticulture and vast lagoons of phytopuration recycle the grey waters rejected by the inhabited vertical farms.

Six multi-functional farm-scrapers

The six gardening towers engraved in a Golden Triangle pile up a mixed programme, superimposing farming scrapers cultivated by their own inhabitants. Like the Dragonfly project in New York, the aim is to repatriate the countryside into the city and to reintegrate the food production modes into the consumption sites.

The megalithic towers are inspired by cairns: artificial stone heaps present on the mountains to mark out the hiker tracks. With clever exploitation of the construction, these six towers pile up housing, offices, leisure spaces in the monolithic pebbles superimposed on one another along a vertical central boulevard.

This central boulevard constitutes the structural framework of each tower. It choreographs the human flows, distributes the natural resources and resolves the waste by sorting and selective composting. The cairns optimise the quality of life of its inhabitants by the reduction in transport, the set up of a home automation network, the naturalisation of public and private spaces and the integration of clean renewable energies.

These six farm-scrapers are pioneering towers aimed at the following 10 objectives:

• The reduction of the ecological footprint of this new vertical eco-quarter enhancing the local consumption by its food autonomy and by the reduction of means of road, rail and river transport.

• The reintegration of local employment in the primary and secondary sectors co-producing the fresh and organic products to the city dwellers that will be able to re-appropriate the knowledge of the farming production modes.

• The recycling in short and closed loop of the liquid or solid organic waste of the used waters by anaerobe composting and green algae panels producing biogas by accelerated photosynthesis.

• The economy of the rural territory reducing the deforestation, the desertification and the pollution of the phreatic tables.

• The oxygenation of the polluted city centres whose air quality is saturated with lead particles.

•The production of a vertical organic agriculture of fruits and vegetables limiting the systematic recourse to pesticides, insecticides, herbicides and chemical fertilisers.

• The saving of water resource by the recycling of urban waters, spraying waters and the evaposweated water by the plants.

• The protection of the biodiversity and the development of eco-systemic cycles in the heart of the city.

• The reduction of the sanitary risks by the disappearance of pesticides noxious for the health and by the fertility and total protection of the phreatic tables.

• The diminution of the recourse to fossil fuel needed for the conventional agriculture in long cycle for the refrigeration and the transport of the goods.

The Asian Cairns project synthesises the architectural philosophy that transforms cities in ecosystems, the quarters in forests and the buildings in mature trees thus changing each constraint into opportunity and each waste into a renewable natural resource. In both the projects urban agriculture, sustainable ways of production and consumption and amalgamating design with nature and natural systems are the key features.

The reasons for embracing and promoting these cohesive ecosystems are compelling where production, consumption and recycling of the systems are generated in a sustainable cyclic manner. It’s not only to produce safer, healthier and more sustainable urban habitats but also to make legible and tangible systems that support life in its truest sense.

Comments (0)