My mother-in-law is making phulkas, Indian flatbreads that are cooked over a flat pan on one side and directly over the flame on the other side. They puff up gently when over the fire; it’s quite theatrical. But I notice that she is using a small saucepan instead of the usual flat tava to cook the first side of the bread. I ask her about it and it turns out that the tava is too heavy for her to lift away from the flame with her left hand as she cooks the second side of the bread.

The saucepan, with its upward edges, is awkward but she’s managed to fix that issue by reducing the diameter of the phulkas. This is the first time I see a saucepan being used this way but the struggle with lifting a heavy pan with one’s left hand strikes me as a pattern. Her working around the problem is a good indicator of an unmet need and a robust opportunity for a better product.

What if these flat tavas were made from a lighter material? What if the handle was designed in a way to alleviate the stress of lifting? What if they allowed exposure to the flame without having to be lifted? These design explorations would lead to a product more fitted to everyone’s needs; a true human-centered design exercise.

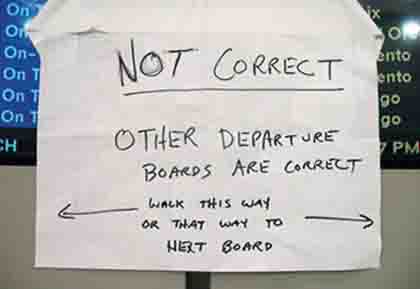

Workarounds, in the world of qualitative research, are golden finds: clear indicators of a need, distinct from a want.

Users devising workarounds don’t necessarily think of their intervention as conscious problem solving and fail to report such appropriation of products, services or spaces in standardised surveys. Such insights can only be accessed through contextual design research that insists on observing how users behave rather than asking them what they’d like to have.

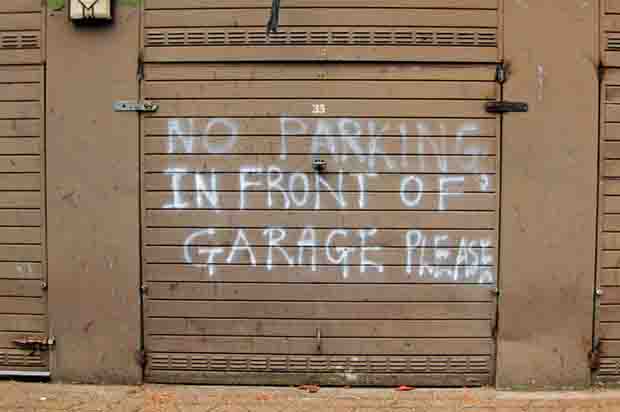

Workarounds occur when users feel the need for quick adaption of environments around them without having to worry about set protocols. They take ownership of tools available to them and assemble their surroundings to fulfill their everyday needs. Informal settlements – unplanned, under-developed, un-approved developments – are rich with such behaviours and present a fertile context for observations.

But how relevant are these insights and observations, if residents of informal settlements are not the target market for a company’s products or services?

Since workarounds expose true human motivations more easily than any other method of research, they offer applicability beyond their immediate context. Such exploration beyond the existing focus area to be applied back to the issue at hand, termed analogous research, enriches design outcomes. Whether it is a product, service, space or strategy, understanding the underlying behaviours results in a more robust ecosystem.

For example, an innovation-consulting firm based in Chicago recently worked on a project for a financial institution, exploring the idea of building trust. They wanted to explore how design can catalyse trust-building in a competitive market. The team looked to other fields where trust plays a pivotal role, such as matchmaking services. Applying insights from an entirely different domain, the team was able to reframe their approach toward the central issue.

Similarly, OpenIDEO demonstrates the importance of analogous research, asking themselves, “What would nature do?” when faced with ‘wicked’ problems. They believe that “by paying attention to nature’s strategies and solutions, we can be inspired to create solutions to critical problems facing humanity and the world.”

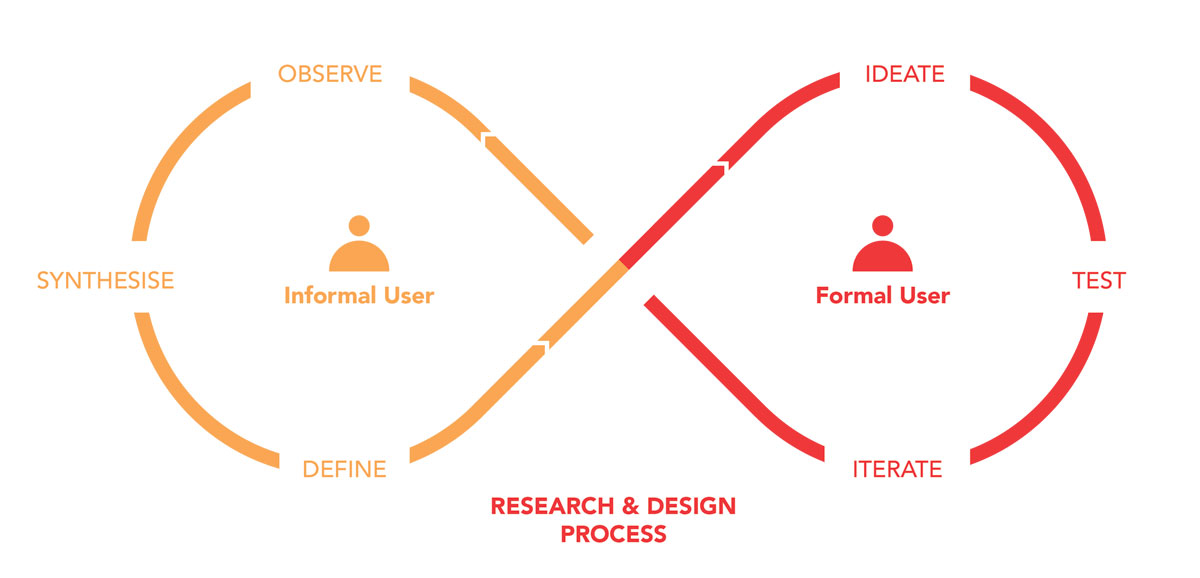

So how can explorations of informal contexts be incorporated into the mainstream design process? Applying learning gathered from informal users onto formal market segments presents a repeatable possibility: learn from one context, test with the other.

With insights from both formal and informal contexts, the resulting products, services, spaces or strategies promise to be highly effective.

Might this inclusion of informal contexts to generate business value inspire special product lines? Perhaps understanding behaviours of these ‘outliers’ will encourage new service models that target both formal and informal markets. This commonality might build bridges across societal hierarchy, cutting across the woes of affordability. In an increasingly unequal world, is this possibility worth fighting for?

RIGHT: Toms Shoes: Built on a charity model, every time Toms Shoes sells a pair of shoes, it donates a pair to a person in need across the world.

In such a scenario, users would feel good about themselves and the brand they’re buying from just knowing that the same company is catering to informal contexts as well. This thinking model can be an evolution of the ‘charitable’ business models of Toms Shoes and Causebox, completing the circle.

This is a heartwarming thought as I focus on my next research track: understanding why my mother-in-law is preparing dough in a plate instead of the eight mixing bowls stored three feet away from her.

Comments (0)