“The physical environment can be designed to communicate an image of time that celebrates and enlarges the present while making connections with past and future.” – Lynch, 1972, p. 1, What Time is this Place?

History and heritage in Indian cities form an intrinsic part of their character. The evolution of cities exhibits different layers in the city’s fabric and heritage forms an important link and narrative to stitch all these layers together. In today’s developing landscape, Indian hill towns continuously face the challenge of striking a balance between preserving their unique culture, accentuated further through their built Heritage in Hill Towns environment, respect for a natural ecosystem and trying to embrace the development of the globalized modern civilization. Traditional architecture and built environment of these towns have become an intrinsic component of their unique culture and spatial manifestation.

The evolution of the built environment in hill towns can be understood through distinct kinds of built environments created in their landscapes in different timelines. The earliest settlement patterns in the hills were of the traditional vernacular settlement variety, which used indigenous materials and systems respecting the existing natural ecosystem and designing the built environment around it.

SUBTLE BEGINNINGS WITH NATURE

Masroor Temple Settlement

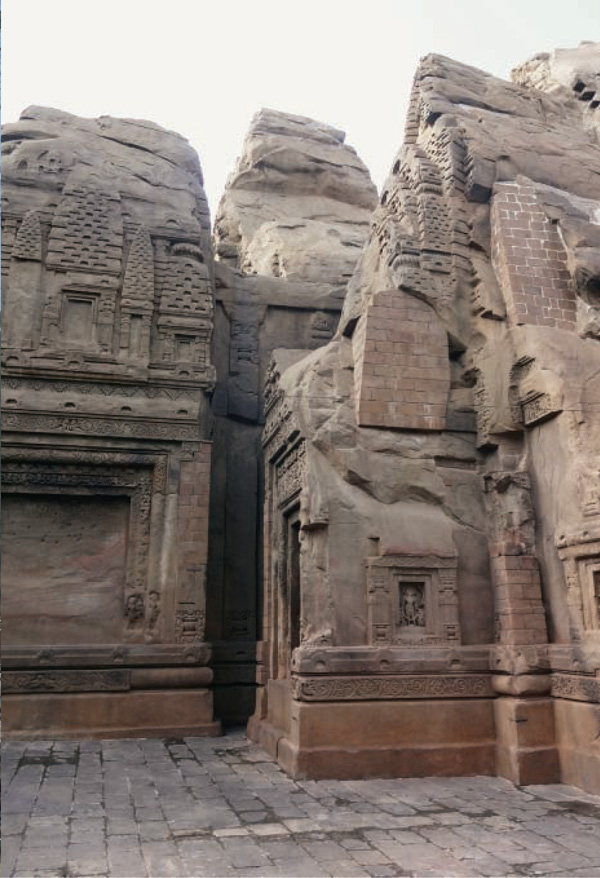

The Masroor Temple complex dates back to the 6th-8th century and is perhaps the earliest kind of built environment with heritage value in the Kangra Valley. These temples are monolithic in nature and follow the Nagara style of temple architecture of Northern India. The temple forms a part of a huge sandstone rock and has a water body connected to it known as Masroor Lake. The temple is built on a well-proportioned cruciform plan. The shikharas and the capitals of the columns consist of figurines of Gods and Goddesses and floral patterns.

The Kangra Fort

The Kangra Fort, dating back to the 4th century, also exhibits similar methods and materials of construction. The basic layout and the gates and boundaries of the enclosure are the remains of this huge fort atop a hill. The temple has an entrance on the axis of which runs the courtyard. From there on, a narrow corridor leads to the fort’s main entrance court. The various gates and enclosures establish the fact that the whole spatial system emphasized power and security through its architecture. Similar developments were part of the urbanization of the hills during the early days with temple complexes and forts built amidst the natural landscape.

Gradually the settlements started growing beyond the temple and fort walls and urban settlement patterns came into existence. The settlement pattern layout in Chamba reinforces the location of the palace and the temple complex on a hill signifying its importance and showcasing heritage as power reinforced through built environment. The generic layout consisted of a typical medieval town system with the residential areas at the foothills and the more important functions of the palace and the temple complex at a higher altitude with axis connections between them.

VERNACULAR TRADITION

The traditional settlement patterns in the hill towns built their patterns with respect to the slopes and the natural systems surrounding them. Local conditions available helped to create new kinds of landscape forms for the cities. Most of these settlements spatially locate themselves in the valleys with the lower foothills for agriculture. Appropriation of the landscape happens when, with the same materials of adobe, stone, slate and wood, different indigenous forms of built form and clusters of residential development are created in diverse regions of the hills with respect to climate and natural setting.

COLONIAL EXPRESSIONISM

With the advent of the British, a new cycle of urban settlements sprang up in the hills. This also happened simultaneously with the industrial revolution in the west, which exhibited its influence in the kind of buildings of historical and heritage value we witness today.

The micro climate of the hills suited the British more compared to the hot humid conditions of the valleys, though access to the hills was a huge issue. However, with the development of the settlements, access connections were established to the hills. That gave birth to the hill railway connection systems like the Darjeeling mountain railway, the Kalka-Shimla railway and the Kangra Valley railway. It was formed through a system of tunnels and viaducts through which the smaller towns were connected. The windy railway system still presents its own architecture patterns of railway engines, coaches, stations, tunnels, viaducts and bridges nestled in the hills amidst the natural setting of flora and fauna. This system now forms part of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites as outstanding examples of hill railways.

|  |

The settlements by the British were initially cantonment towns that later developed into bigger urban centers. These towns were mostly situated on top of the hills with ridges and valleys forming part of the settlement and most of these towns showcase some of the best examples of colonial architecture in India.

| |

|  |

The emphasis was to conserve the natural setting, which finally resulted in generating a natural heritage for these hill towns along with the built heritage.

Mall roads, which functioned as the pedestrian high streets, were found in most of these settlement patterns. They exhibited a pedestrian quality flanked with shops and a distinct colonial character for the street. There was an eclectic mix of architectural styles that the buildings in these urban settings exhibited.

The Viceregal Lodge is perhaps one of the finest examples of neo-gothic architecture in these hill towns. Designed by Henry Irwin, this was the viceroy’s residence when Shimla acted as the summer capital of India during the British Raj. Several other notable examples of unique architecture include the Railway Board building, which is a cast iron and steel structure and the Oberoi Cecil and Gorton Castle hotels.

Apart from the architectural character of these individual buildings, the public space networks in these cities were a remarkable feat with pedestrian routes along ridges acting as promenades stitching the whole city together and opening up to squares and plazas in the city center like the Ridge in Shimla and Gandhi Chowk in Dalhousie.

|  |

REGIONAL INFLUENCE

There has been considerable regional influence on these hill settlements from Tibet and Nepal where the architecture and settlement patterns of these areas have adopted a more regional influence based on religion and its subsequent manifestation in living patterns. Thus, the monastery settlements in Leh, Dharamshala and Sikkim show this religious influence in building architecture and town layout. They also exhibit the conversion of the mythical construct of the religion and faith into spatial forms.

JUXTAPOSITION OF OLD WITH NEW

With time, the present condition of these hill towns shows different character areas all existing together and trying to amalgamate. The town would have these structures of historical and heritage importance as artefacts and magnets in between the newer development patterns and dilapidated older ones. The transformed patterns of these settlements today call for a critical understanding because the older structures have transformed certain elements and retained certain elements. The elements that have been retained have shown closer and longer association of place memory with the people of these settlements. These elements and spatial systems have to be understood so that the new development can link to these elements and through this add to the memory of the place rather than appear to be random urban development completely out of sync and character.

LEARNING FROM THE HILLS

The hill towns have their stories of history as a narrative exhibited physically through their built environments. The history, through the intangible aspects of culture and social patterns of people, helps to reconstruct the place and community in these towns. The physical aspects of these towns are rooted in this social and cultural perception. Thus, future settlements could take a cue from this so that respect for the natural setting is maintained.

The kind of public space structure in terms of the open spaces, squares, plazas, the promenades, the view corridors all functioning at a human scale dotted with monuments of heritage importance is an important layer in the structure of the city. An attempt could be made to also understand or rejuvenate this layer in our other cities because this public place network on a human scale not only ties the city together but also improves the quality of life of these places. Walking through this public pedestrian network and encountering heritage buildings en route is really a pleasurable visual experience.

The structures of valuable heritage importance have become examples of monument heritage. These monuments exist in an urban and natural setting and have deep connections with their surroundings.

Understanding the heritage of these monuments will only be possible when the network and system are understood as a whole.

Heritage and preservation of a particular building are important, more so for our future generations. The tangible aspect of the heritage of the building could be connected with but the history of the place can only be understood as a whole. We need to preserve and connect to our heritage in such a manner that the history of the place and not just the individual monuments is understood as a spatial system. This would result in a more holistic understanding of evolution of places, people, culture and the built environment.

Comments (0)