Good infrastructure for movement is vital for the functioning of a city. The continuity of these lines of infrastructure and their network offer possibilities for making these spaces usable to different groups of citizens, while new technologies open up the possibility to reshape and remould these networks for multiple usages.

By the word ‘infrastructure’ we mean all the lines of connectivity within a city: roads, waterways, railroads and airports, as well as underground cables and pipes for water, sewage, electricity and the Internet. They all fall within the term ‘urban infrastructure’.

As cities develop, the demands we place on their infrastructure change. So, what was ‘good’ urban infrastructure in a city earlier may fall drastically short of what is desirable today. As cities evolve over decades and change to meet fresh requirements of their ever-changing citizens, infrastructure needs to be continually adjusted and fine-tuned, and sometimes drastically altered to cater to the new demands made by citizens.

As time passes, everything in cities changes. In fact, the only constant in the life of a city is change! The successful city of the future will therefore have to keep on renewing and reinventing itself to facilitate the changing needs of its changing citizens.

It is in this ability to adjust and change its infrastructure that there resides the challenge – and also the immense possibility – of creating urban landscapes, which can make cities more liveable.

Short History of Urban Infrastructure and Urban Form

The choice of the pattern of urban infrastructure, often based on the landscape on which the city was conceived, or as defined by the designer’s pencil, gives the city an identifiable urban form. As time passes and urban society evolves, some of the original infrastructure loses its function but remains visible within the city. Other parts of the infrastructure adapt to changing needs.

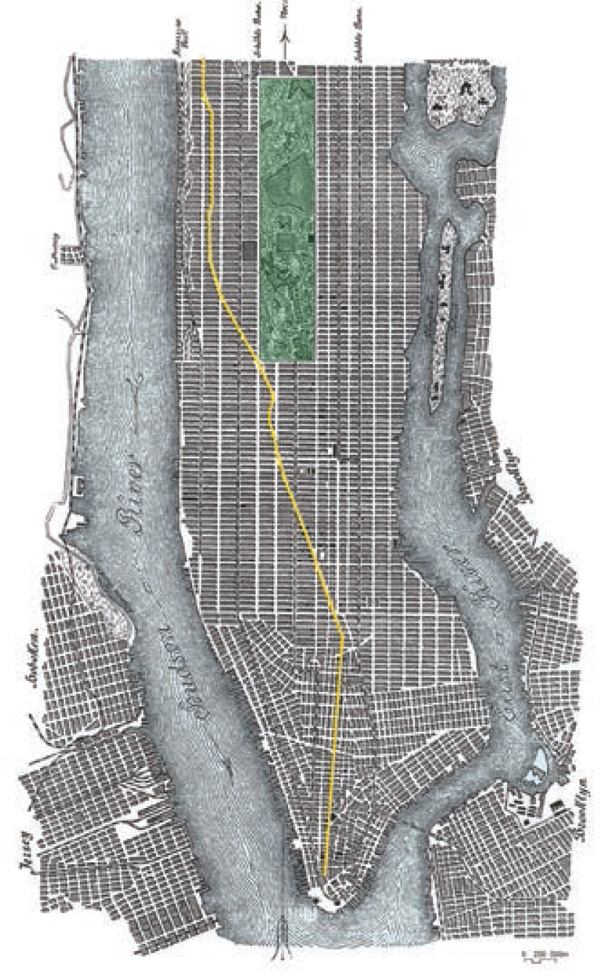

An interesting example of this is the city plan of Manhattan that was conceived in 1811. The orthogonal grid pattern of streets drawn to take care of the urban infrastructure is, after 200 years, in principle unchanged. However, the city has evolved dramatically from a low-density town to a high-density metropolis. The volume of the built-form is several times larger than conceived in the original plan; vehicular traffic of enormous magnitude now races through its orthogonal grid network and shipping on the rivers has decreased in importance.

In the cities of America and Europe, in the 19th century, the emigration of large populations to urban centers fueled by industrialization and the rise of new modes of vehicular transport formed the main impulse for transformation and growth of existing cities. Then again, at the beginning of the 20th century, the second industrial revolution had a direct and indirect effect on the development of infrastructure in urban centers.

The orthogonal grid pattern of streets in Manhattan was created for optimal east-west movement between the two waterfronts. The harbors and piers on the Hudson River on the west and the East River on the east were seen as extensions of the east-west streets, whereby the ideal distance of 75 meters between the piers was extended to create the streets. Because of the regular (150 times) repetition of these streets, they could be kept small in their size with a width of 25 meters.

In the north-south direction a limited number of 12 avenues were created with a greater width of 40 meters. This pattern of streets resulted in building blocks of roughly 75 meters by 250 meters. The street pattern of east-west streets and north-south avenues was projected on the landscape without any differentiation.

It was only in the second half of the 19th century that space was created for the Central Park. Broadway, which was an old road that existed before the grid was imposed on it, was retained for financial reasons since the expropriation of the then existing properties would have been just too expensive.

It was much later that the exceptional position of Broadway in the otherwise neutral orthogonal grid elicited praise as an interesting design element. Then in 1927 the ‘master- builder’ of mid-20th century New York, Robert Moses, proposed the improvement of the basic street pattern on the West Side, including the building of the Henry Hudson Highway, the creation of the Riverside Park and the erection of a bridge over the Harlem River.

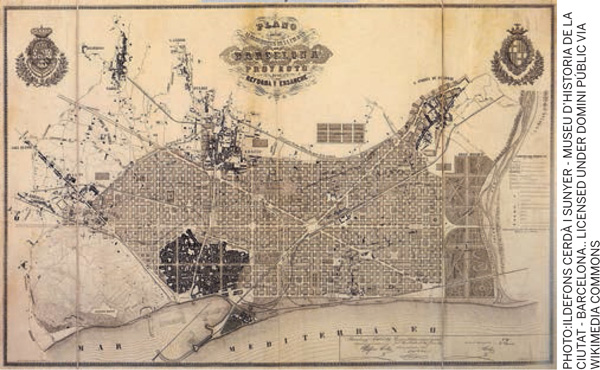

In contrast, designer Ildefons Cerda based the plan for the extension of Barcelona (1859) as an antidote to the congested medieval city. In his design of the pattern, he tried to take into account the east-west layout of many creeks on the site. Also, because of this, many of the older roads in the area could be accommodated in the new pattern of the urban infrastructure. The final dimensions of the urban block of 113 by 113 meters was the result of Cerda’s intent to create an urban mix of different groups and functions, besides allowing for ease of urban movement. In deciding the dimensions of the streets, Cerda was guided by technical as well as aesthetic considerations, such as the planting of trees.

In the early part of the 20th century, the economy of Barcelona was poised to grow but all this came to an abrupt halt due to the Spanish Civil War. It was only when Barcelona was chosen as the venue for the Olympic Games in 1992, that the city got an enormous impetus for growth and transformation. The Metro network was modernized, new peripheral roads created, the airport extended and the city transformed to create a dynamic new waterfront.

What the examples of Manhattan and Barcelona both show is that the pattern of urban infrastructure needs to adjust and reinvent itself as the city grapples with new technological and societal demands.0 By not looking at these changes simply as a necessity, but as a chance to renew and create better cities, they can become more liveable.

In their response to these changes lies the difference between cities that fail to see the opportunities and those that pioneer and succeed.

In the last decades some of the cities have grabbed this chance to give more space for landscape and environment by creating green spaces for their citizens to use, make their cities more environmentally friendly, water-resilient and reduce noise and air pollution. Three examples illustrate this point:

|  |

| |

The Madrid Rio Project – Madrid, Spain

With the building of the M30 motorway in 1970-1979 along the river Manzanares, the historic relationship of the city of Madrid with the river was lost. Not only was the motorway a great physical barrier between the city and the river but it was also responsible for many environmental problems.

Then at the beginning of the 21st century the city of Madrid took the unprecedented step to ‘under tunnel’ the motorway along the river for a stretch of nearly 20 kms and create a fantastic urban park on top of the motorway.

With this urban intervention the Spanish capital was freed from air and noise pollution of 200,000 cars per day and the physical relationship between the historic inner city and the western quarters was achieved. This intervention in the urban infrastructure created a great landscape element by linking all the existing parks and gardens along the river Manzanares and creating a vast urban park.

In the design of this new landscape element, the footpaths, cycle paths, boulevards, squares, sports facilities and playing fields have been connected to the existing urban areas, thus giving the citizens of Madrid access to sport and recreation in the neighborhood of their homes.

The different elements of the newly designed landscape are mutually connected by the ‘Salon de Pinos’ (literally, the Pine Tree Ballroom) which owes its name to the thousands of Pine trees that have been planted there. Since these Pine trees grow in the hills outside of Madrid, their use in the center of Madrid, as it were, literally brings the outside landscape into the city. In the warm Spanish summers, they offer ample shade to the park users. The unique quality of the Pine trees is that they can flourish on rocky, dry subsoil and that is why they were utilized on large parts of the park, which is built on top of the concrete of the underground tunnel.

The Cheonggyecheon River Restoration – Seoul, South Korea

The Cheonggyecheon stream flowed over a length of nearly six kms through the center of Seoul in the middle of the last century. After the Korean War (1950-1953), many uprooted civilians settled in improvised houses along this stream. This resulted in the pollution of the stream, which finally led to it being covered up by concrete in 1958 to make space for a road. A decade later, an elevated highway was created over this space. Yet again after a few decades, by the turn of the century, this area had become a major urban eyesore because of its environmental pollution. A new set of goals to discourage private cars in the center, promote public transport and increase the amount of green landscape spaces in the city resulted in the drastic decision to remove the elevated highway and bring back the river into the city.

Within a period of three years, the area was converted into a modern linear urban park. A couple of old traditional bridges were reconstructed, pedestrian and cycle paths created, which have resulted in the revival of some of the old cultural events in this urban park in the center of the city. While the bus and metro networks have improved, the use of private cars in the central part of the city has been discouraged.

|

|

The Cheonggyecheon river project is an excellent example of how a decisive urban intervention has led to the reutilization of the urban infrastructure space to create an element of urban landscape that has greatly increased the liveability of the city. The restoration of water and green landscape has increased the quality of air, connected the northern and southern parts of the city and given a marked impulse to the urban economy. Additionally, the urban ecology has been enriched and the city has become more water-resilient.

High Line Park – New York, USA

It was in 1860 that a rail track to carry freight was established in the less densely populated western part of Manhattan. By the 1930s the vehicular traffic of cars on roads had reached such intensity that it was decided to raise a nearly two km long section of the rail track nearly nine meters above the street level to avoid traffic hazards, giving it the name The High Line. It was mainly used to carry freight from the many industrial warehouses in the area.

By the early 1980s the rail track had however lost its function and the disused raised section of the track started to deteriorate.

Then by the end of the 1990s, when the city administration had decided to tear down this remnant of Manhattan’s industrial past, a group of citizens started an initiative to convert this raised stretch of old infrastructure into a linear park. After years of discussions, the work of repurposing an old railway track into an urban park began in 2006.

PHOTO: BEYOND MY KEN - OWN WORK. LICENSED UNDER GFDL VIA WIKIPEDIA

The new design of this urban park refers regularly to its industrial history, while acknowledging its present day setting in 21st century Manhattan. The High Line Park runs even today through and alongside industrial buildings where it brought and collected freight, and the elements of the industrial past have been retained and reused in the new design of landscape and public domain. Old linear elements of cast iron have been combined creatively with new wood and concrete elements. Plants and trees, which had grown naturally in the period of disuse of the rail track, have been ingeniously incorporated in the new landscape.

The creation of this new urban landscape on top of the old line of urban infrastructure has given a great economic impetus to the buildings and areas abutting it. Many commercial and cultural projects have been initiated and developed around the High Line Park, which have not only been of great use to the citizens of Manhattan, but are also being thronged by tourists.

The increased income due to property taxes as a result of higher property values due to this redevelopment was calculated in the development plan of the High Line. The transformation process has been helped by liberalization of the zoning from the originally purely industrial use to commercial and residential functions.

The examples of the projects in Madrid, Seoul and Manhattan are inspiring examples of reusing old lines of infrastructure by converting them into landscape elements of great quality and making the cities more liveable for their citizens.

Comments (0)