Urban parks are located within a city to offer recreation and green space to residents and visitors to the city. Today, there is a tremendous flowering of artistic and cultural activity in urban parks and people value the time they spend in parks, whether walking a dog, playing basketball or having a picnic. Along with these leisure facilities, parks can also provide measurable health benefits, from providing direct contact with nature and a cleaner environment, to opportunities for physical activity and social interaction. Vegetation in cities also reduces the higher temperature effects of urban heat and trees help improve air quality by removing pollutants from the atmosphere. Since urban neighbourhoods have high concentrations of pollutants, urban parks are especially important to filter the air.

Additionally, urban parks create a sense of place by connecting residents to one another and to their larger environment. Today’s best urban parks are multi-use destinations and catalysts for community development. One can find a variety of great urban parks all over the world. All of these parks provide a green oasis in an urban setting either as a place to understand and relate to nature or as a place for social and cultural exchange.

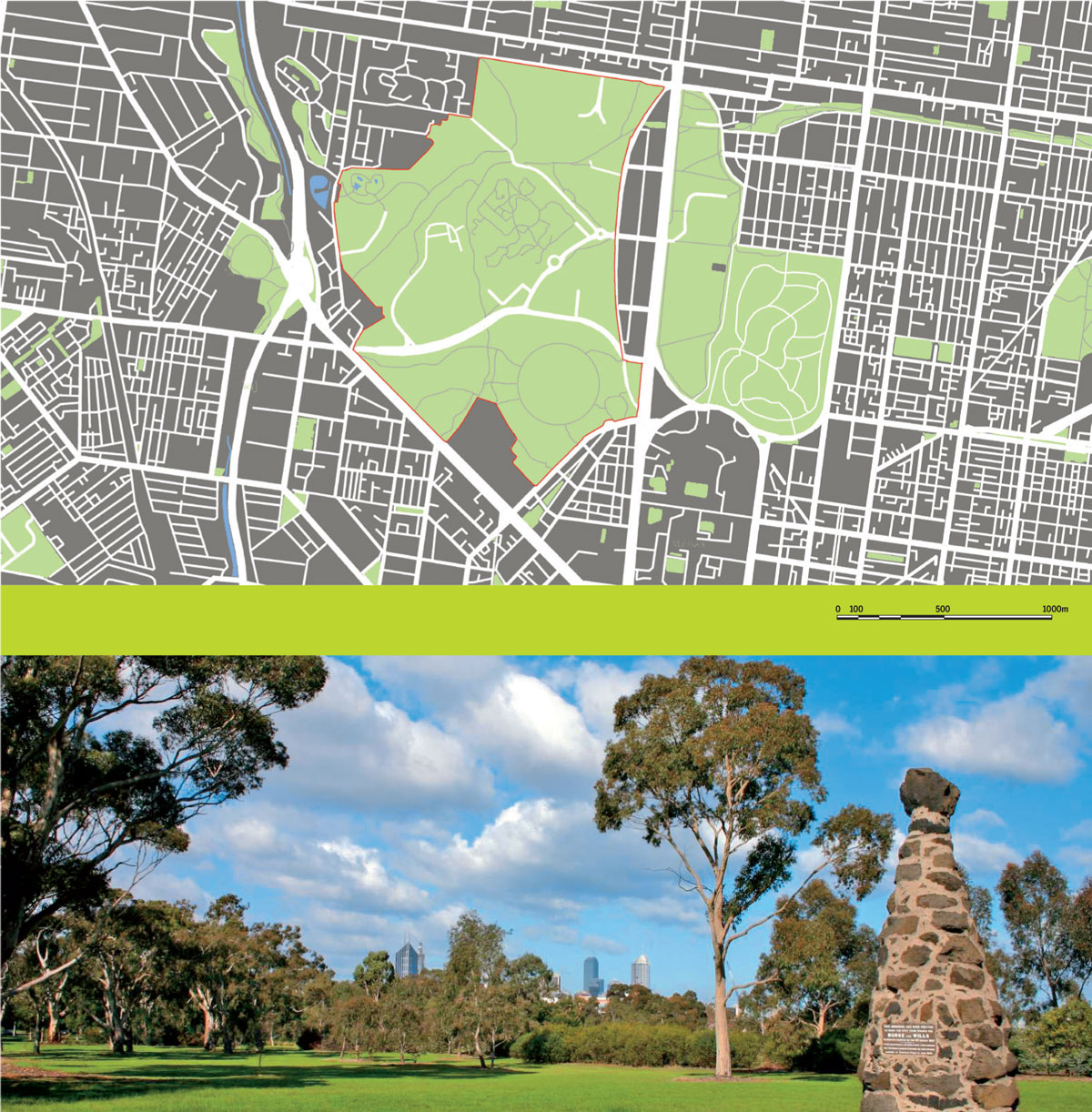

MELBOURNE, ROYAL PARK. 181 HA

Royal Park is the largest of Melbourne’s inner city parks and its wide open spaces make it hard to believe you are still in the city. It is located four kilometers north of the Melbourne Central Business District. Since its earliest days as designated parkland, Royal Park has had a strong tradition as a place for relaxation and sport, which continues today. Choose your sport and you’ll find the facilities, whether tennis, golf, football, baseball, cricket, netball, hockey, cycling or walking. Stretches of open grass alternate with areas of lightly timbered eucalyptus forest, home to possums and a huge variety of birdlife, including rosellas, wrens, robins and birds of prey.

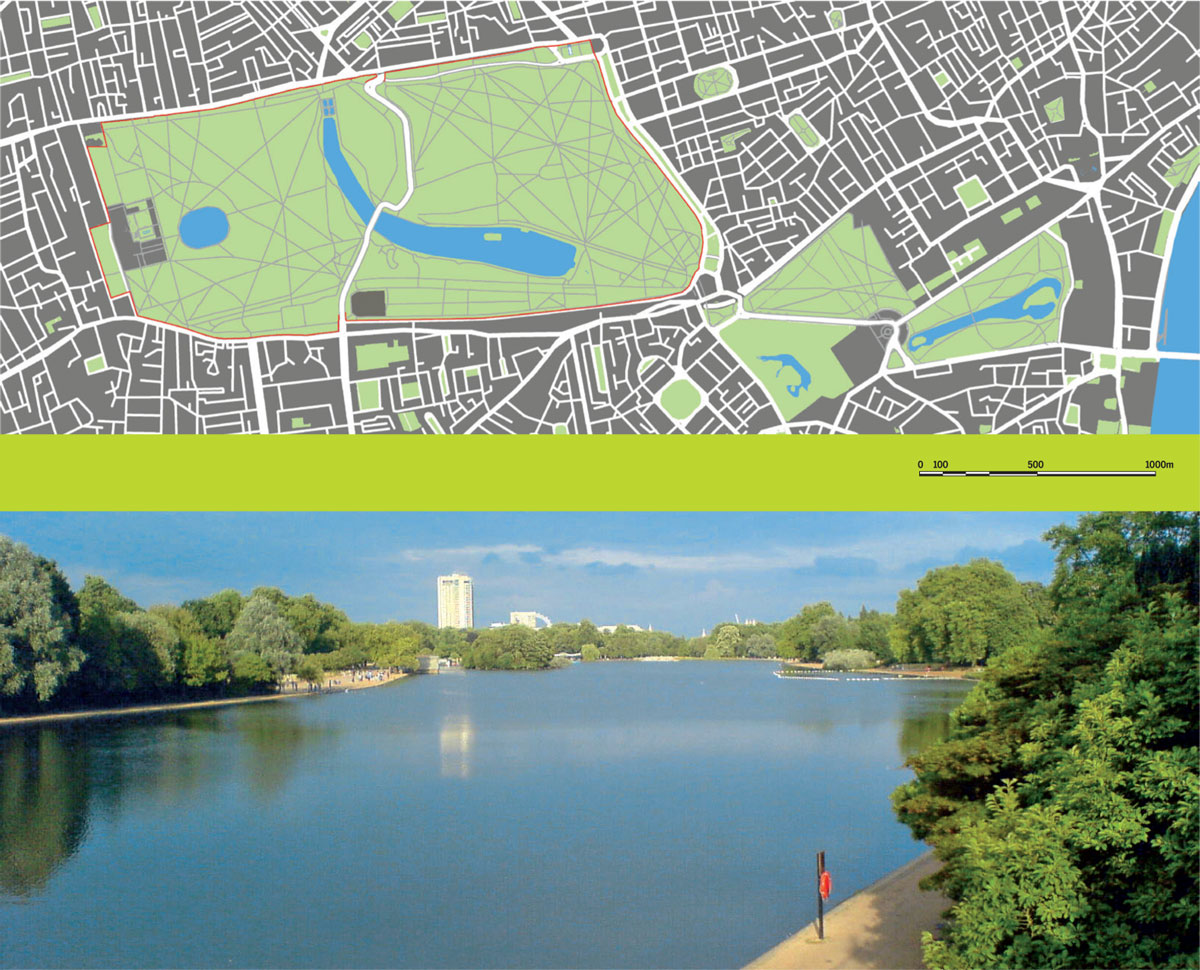

LONDON, HYDE PARK (140HA) + KENSINGTON GARDENS (111 HA) = 251 HA

Kensington Gardens are generally regarded as being the western extent of the neighbouring Hyde Park from which they were originally taken, with West Carriage Drive forming the boundary between them. Kensington Gardens are fenced and more formal than Hyde Park. Hyde Park is famous for its Speakers’ Corner, which has acquired an international reputation for demonstrations and other protests due to its tolerance of free speech.

BENGALURU, CUBBON PARK. 76 HA

Cubbon Park is a landmark ‘green lung’ area in Bengaluru contributing to various historical monuments and government buildings, cultural, scientific institutions besides being a park with flowering plants, towering trees, shaded groves and a vast expanse of green.

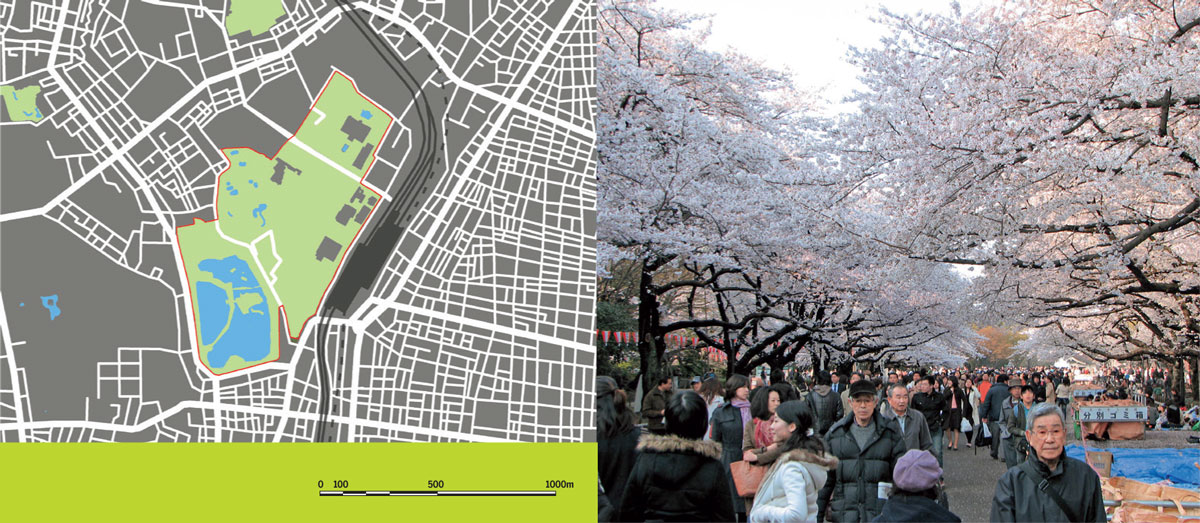

TOKYO, UENO PARK. 68 HA

Ueno Park is a large public park next to Ueno Station in central Tokyo, famous for the many museums found on its grounds. The park is one of Tokyo’s most popular and lively cherry blossom spots with more than 1000 cherry trees lining its central pathway.

SINGAPORE, GARDENS BY THE BAY. 63 HA

18 eye-catching tree-like structures dominate the Gardens’ landscape with heights between 25 and 50 meters. They are vertical gardens that perform a multitude of functions, which include planting, shading and working as environmental engines for the gardens.

NEW YORK, CENTRAL PARK. 341 HA

Central Park is located in the centre of Manhattan. Especially during the weekends, when cars are not allowed into the park, Central Park is a welcome oasis in this hectic city. In 1857, designer Frederic Law Olmstead’s goal was to create a place where people could relax and meditate. After the appointment of Robert Moses as New York City Parks Commissioner (1934-1960), the focus of the park shifted from relaxation to recreation. Today, Central Park is the most visited urban park in the United States with around 37 million visitors annually.

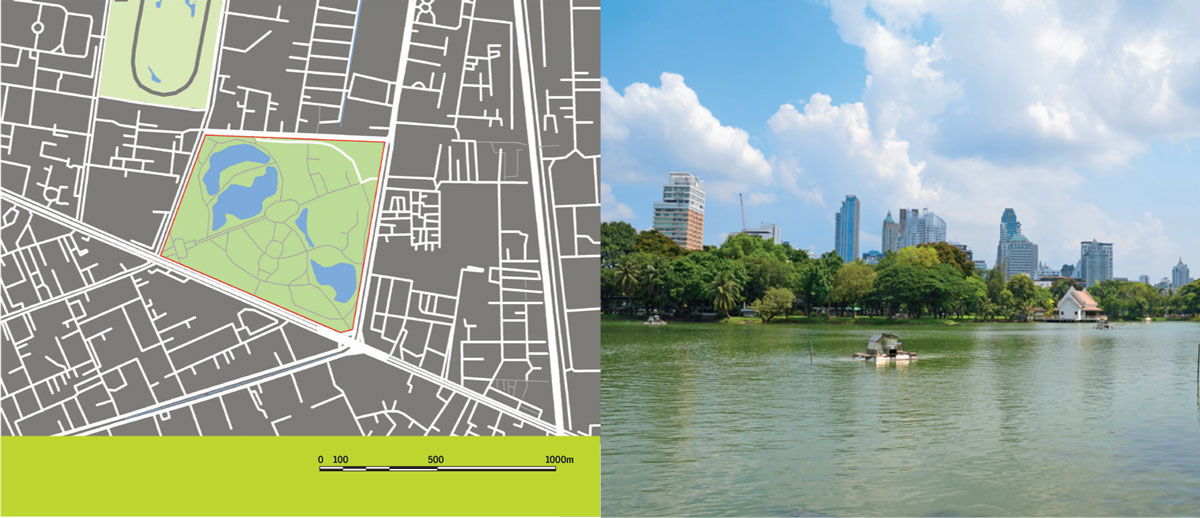

BANGKOK, LUMPHINI PARK. 58 HA

This park offers rare open public space with a lot of trees, beautiful flowers, large lakes, playgrounds and various types of animals in the Thai capital. Lumphini Park is a multi-purpose park, providing many activities for citizens and tourists.

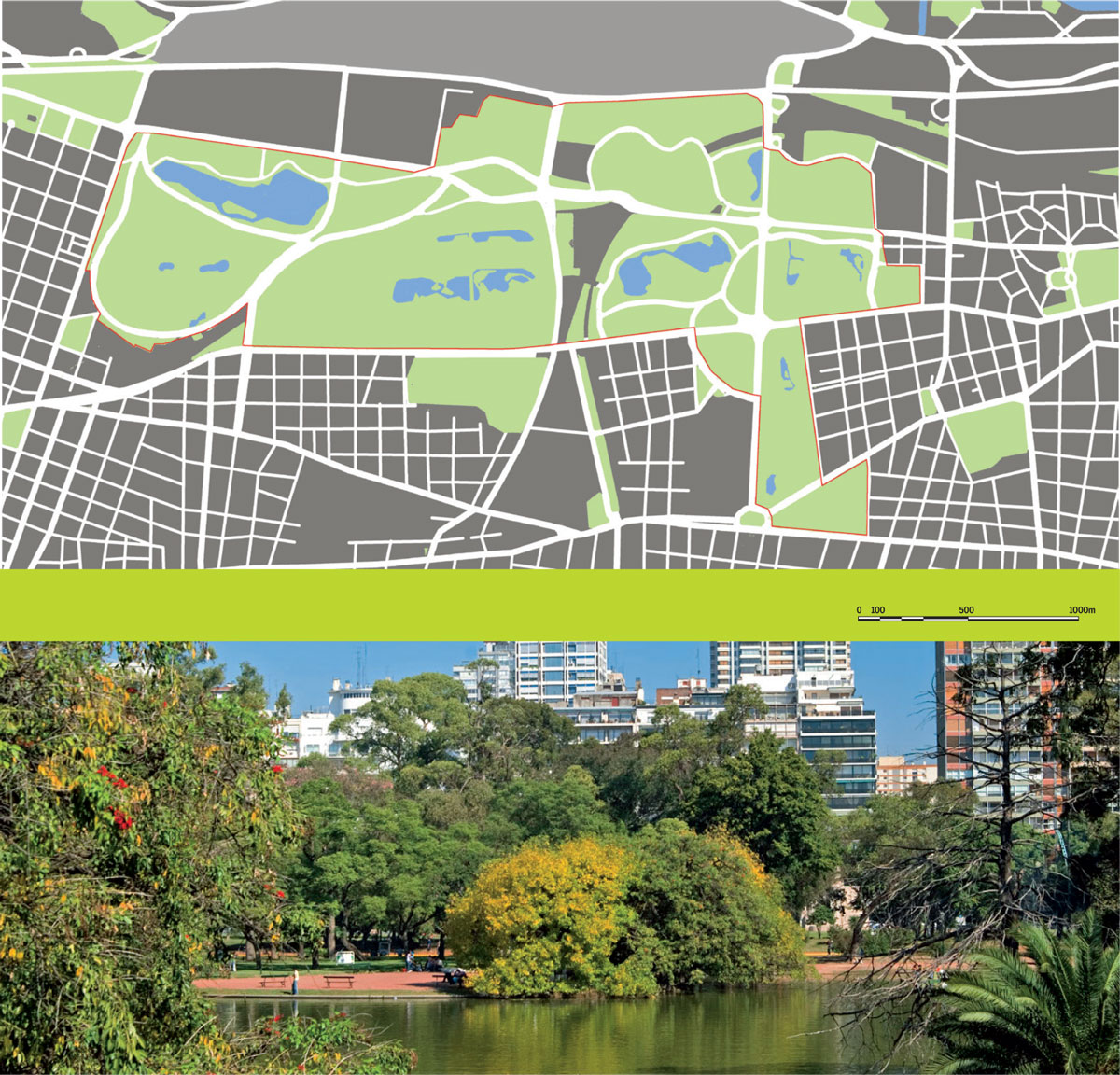

BUENOS AIRES BOSQUES DE PALERMO. 400 HA

The Bosques de Palermo, also known as Parque Tres de Febrero, is located in the neighbourhood of Palermo in Buenos Aires. The park has been in existence in a variety of forms since 1875 and over the years it has undergone additions including a zoo, a botanical garden and an exquisite rose garden, as well as the world’s largest Japanese garden outside of Japan. The park is popularly used by pedestrians and cyclists and is busiest on the weekends as this is where families come to play and for picnics. The park is also known for its Poets’ Garden, with stone and bronze busts of renowned poets.

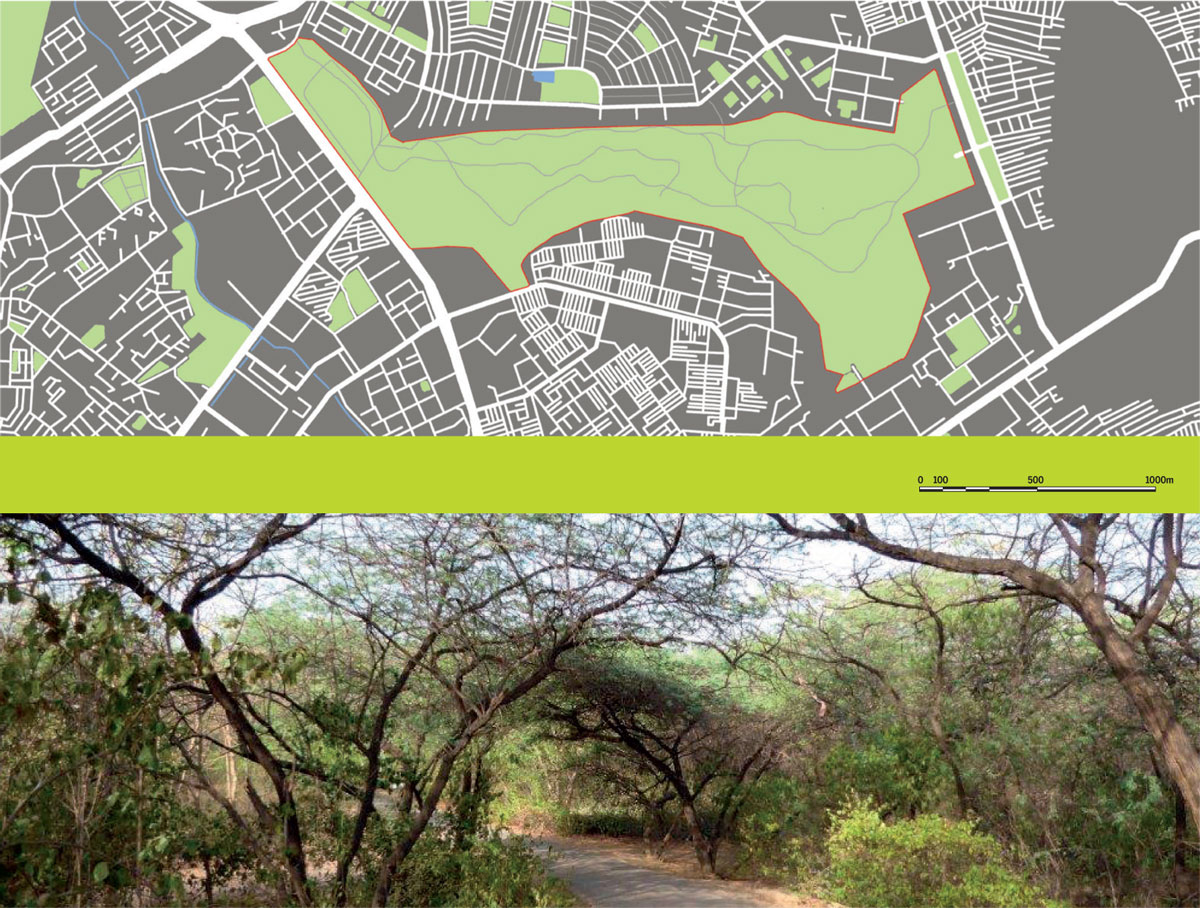

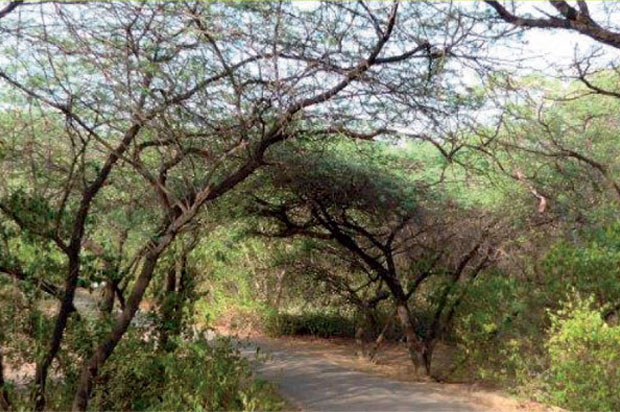

DELHI, JAHANPA NAH CITY FOREST. 175 HA

Revered as the green lung of the city, Jahanpanah City Forest is sprawling and lush green with huge trees, natural trails and chirping birds in the middle of South Delhi’s hustle and bustle. It’s considered to be a great running location, with a 6.6 km paved trail through the park. Most of the trail is covered in thick foliage that provides a good respite from the heat. Besides running, one can cycle as well, along with playing in the little parks all over Jahanpanah Forest.

Comments (0)