One very early summer morning, I stood in the midst of downtown Chicago, the area jam-packed with high-rise buildings. I could see neither a car nor a pedestrian on the streets around me. That calm moment with the wind whistling between concrete buildings and the light of dawn painting the tips of skyscrapers allowed me to experience a new Chicago. This was different from the typical rhythm of busy people and indistinct noises at high volume. It was that change of dynamic that gave me the unfamiliar feeling in the familiar city.

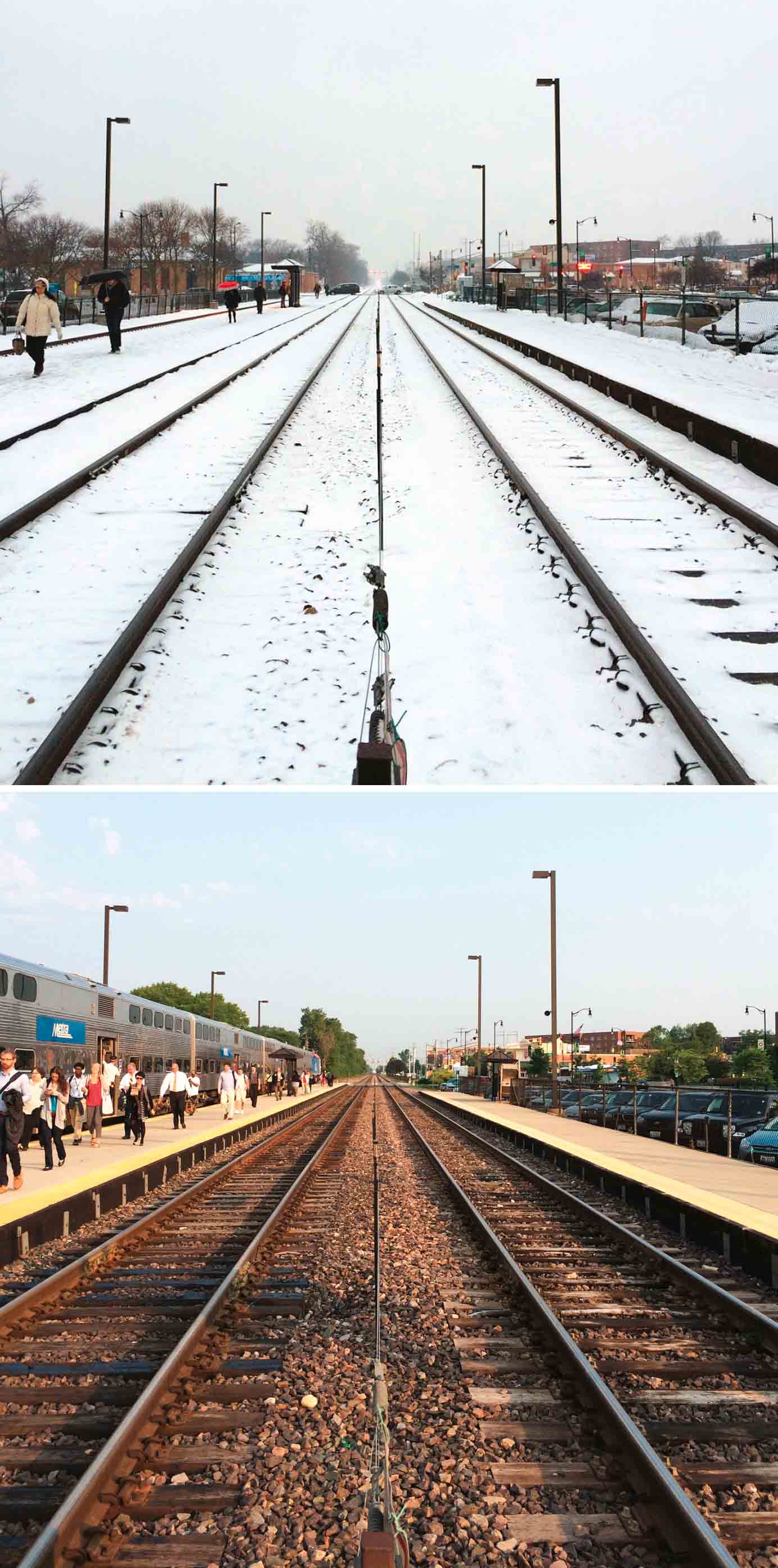

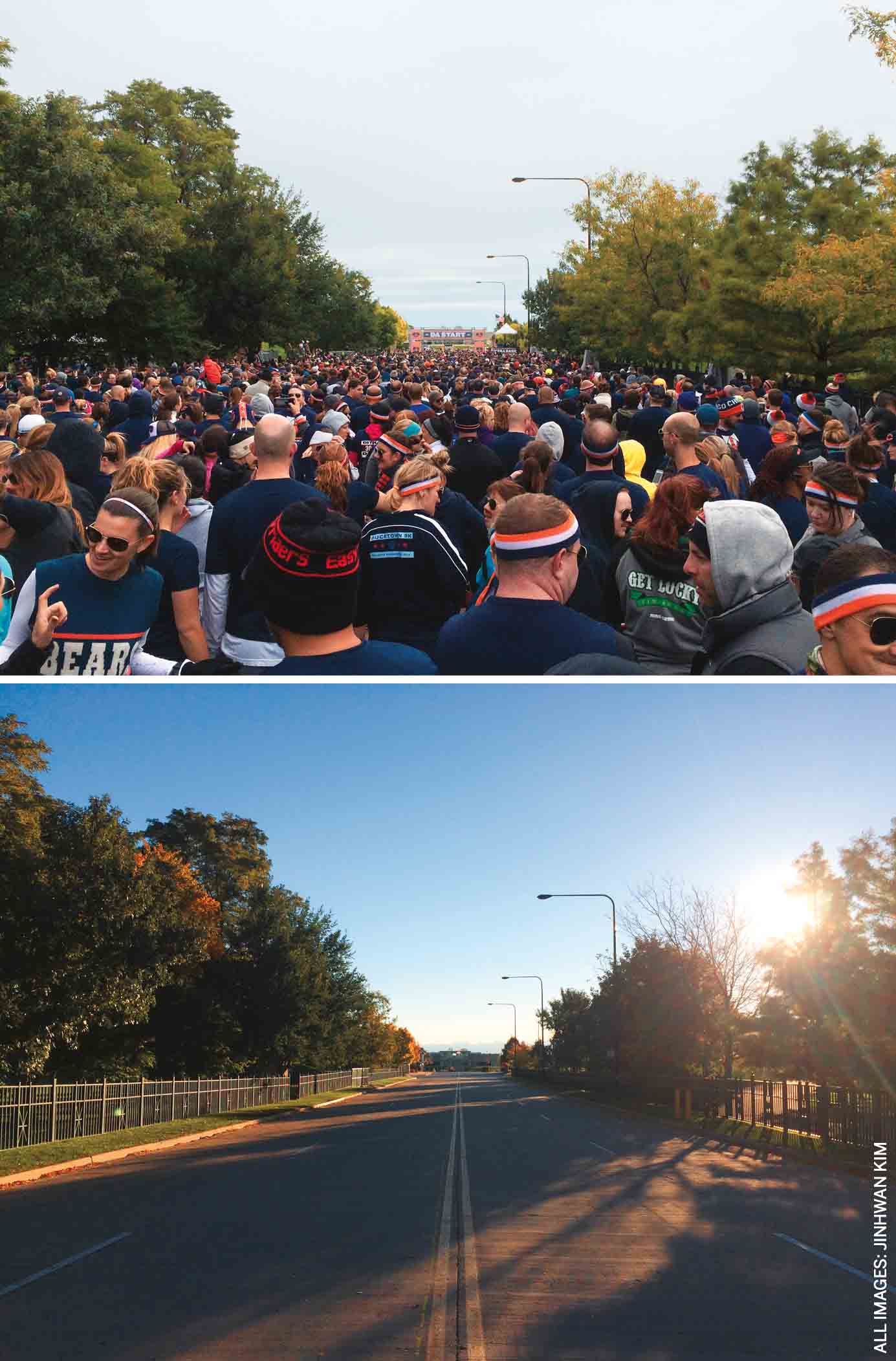

We often forget that people and their activities within the public realm of a city make it vivid, rather than the tall buildings or lights. Looking through public spaces with surprisingly diverse uses, I wanted to capture such contrasting scenes around Chicago. I found various city expressions in pairs with differing events, seasons and times.

|  |

- Text and images by Jinhwan Kim

Comments (0)