On May 14, 2017, several thousand Muscovites protested a new law aimed at demolishing Soviet-era housing dating back to the 1950s and ’60s. The majority of the buildings targeted for demolition are the so-called ‘Khrushchevki’ that were rapidly constructed in a massive building boom shortly after Khrushchev ascended to power. The law is entitled ‘On the Status of the Capital of the Russian Federation’, but colloquially referred to as the Law for Renovation. The intent, however, is not to renovate. In exchange for demolishing their existing homes, residents are promised a new apartment of similar size, generally within the same rayon (city region).

On the surface, this programme seems like a positive development for the residents of these apartments, which are often cramped and severely deteriorated. Nevertheless, the law ignores several of the peculiarities of Moscow land use and housing practices that could leave a significant minority of homeowners worse off than they were before.

One of the participants in the May 14th protest was Anna Sorokina. Anna, a former professor at the Russian State University for the Humanities, had never attended a protest rally of this nature before. She decided to attend because her five-storey home had appeared on a list of houses to be demolished. According to Anna, the pronouncements of the Moscow city government that everyone will be made better off once they have been transferred to a new apartment misses an essential point: “It’s a neighbourhood. We don’t just live in the apartments themselves, we live in the neighbourhood as well.”

In Soviet/Russian planning jargon the term ‘neighbourhood’ typically refers to a micro-rayon or micro-region. A rayon or region, is an assemblage of micro-rayons. The legislation, as currently drafted, promises that residents would be resettled within the same region or the neighbouring region. It is important to note, however, that each Moscow region (rayon) can house more than 100,000 persons. Therefore, the promise of relocation within the rayon is not analogous to relocation within the neighbourhood. Many of the residents protesting this action fear that through resettlement they will lose access to social networks that have been built over the course of decades. In addition, a traditional Soviet micro-rayon was designed to provide residents with equivalent access to green space, schools and transit. Major roads did not enter the micro-rayon in order to provide safe refuge for children walking to school. It is unclear whether or not the replacement buildings would adhere to these standards, given the lack of appropriate building sites within Moscow.

“We don’t just live in the apartments themselves, we live in the neighbourhood as well”

Evolution of the Khrushchevki

Russians are fond of the proverb “there is nothing more permanent than the temporary,” and the Khrushchevki epitomise this concept. They were originally built as temporary structures to address an acute housing crisis that had long festered absent dissent during Stalin’s rule. Khrushchevki were, for many Muscovites, the first modern home they had ever occupied after leaving the village. For others, they meant the first apartment that was not shared with one or more other families. Yet, while the political intent of the Khrushchevki may have been as temporary structures, their engineering suggested otherwise. Many were built of pre-stressed concrete panels. They have no elevators or other moving parts. These features have allowed the Khrushchevki to deliver a habitable – if somewhat uncomfortable – existence to their residents for half a century. Khrushchev himself admitted as much during his famous 1959 ‘Kitchen Debate’ with Richard Nixon on the comparison of Soviet and American housing models, bragging, “We build firmly. We build for our children and grandchildren,” as opposed to American homes that he claimed were only designed to last for 20 years. In the 1970s, the Soviet Union began to transition away from standard five-storey to nine-16 storey buildings with larger floor plans, however the lowest cost option remained five-storeys, which required less costly materials and less intensive capital utilisation.

Bottom: Aerial view of a Moscow micro-rayon

The most common Khruschevka was a two-bedroom apartment with a living space of 55 sq. m.. The kitchens were approximately 5-6 sq. m., and ceilings were 2.5 m. high. The early buildings were, in many cases, not merely utilitarian but inadequate as single-family housing. To begin with, the breakneck pace of construction often rendered the ‘completed structures’ unfinished. A Russian professor of architectural history noted his personal experience that “snow would blow in between the panels” that had not been properly sealed. Perhaps an even greater insult to Russian sentimentalities, the new structures possessed small kitchens, thereby depriving families of their traditional gathering place. They were nevertheless a significant upgrade from a communal apartment that provided no common space for family gatherings. New residents were left to their own ingenuity to complete their apartments. Not knowing if and when they would ever be able to move into a larger apartment, families labored to extract the maximum amount of liveability out of every square metre.

This process of incremental improvement only accelerated after Russia’s independence. Many Khrushchevkis today are Soviet on the outside, IKEA on the inside. While some families took advantage of privatisation to upgrade to larger, more modern apartments, those who remained in their original government-issued flats often had significant disposable income to reinvest in interior renovation. Ironically, the fact that Soviet apartments required such active intervention to make them habitable is one reason the idea of abandoning these apartments to the wrecking ball is at best a bittersweet experience.

Micro-rayons

Plans to demolish Soviet-era housing were evaluated in the Moscow General Plan (GenPlan2025), published during Moscow’s housing bubble prior to the global economic recession. With the price of new modern housing hovering at $7000/sq. m., builders salivated at the possibilities of replacing the five-storey buildings with towers of 20 or more floors. Many individual structures were demolished on an ad hoc basis. The plan indicated that the government would demolish approximately 10% of the total housing in the city, equivalent to 25 million sq. m., while constructing approximately 100 million sq. m. of new housing. This would have been a dramatic shift for a city that is already densely developed. One of the most controversial strategies was to develop new spaces on vacant land in existing neighbourhoods despite the fact that these areas were deliberately left vacant by Soviet planners to maintain a sustainable density. Significant protests and opposition arose in response to these plans.

Three concurrent events helped to put the plan on hold for a period of time. The first event was the recession, which greatly dampened enthusiasm for new construction. The second was the annexation of regions to the south of Moscow with plans to build a second downtown, dubbed ‘New Moscow’, to relieve the need for additional density within the city. Finally, Moscow’s longtime pro-construction mayor was replaced in 2010 robbing the GenPlan of its most powerful backer.

Now it appears that the GenPlan has risen from the dead in another form. Densification is no longer the principal goal of the plan given the continued falloff in demand due to the weak economy. Rather, the plan is being promoted as economic stimulus for the building industry that will help the local economy as well as the individuals living within Khrushchevki.

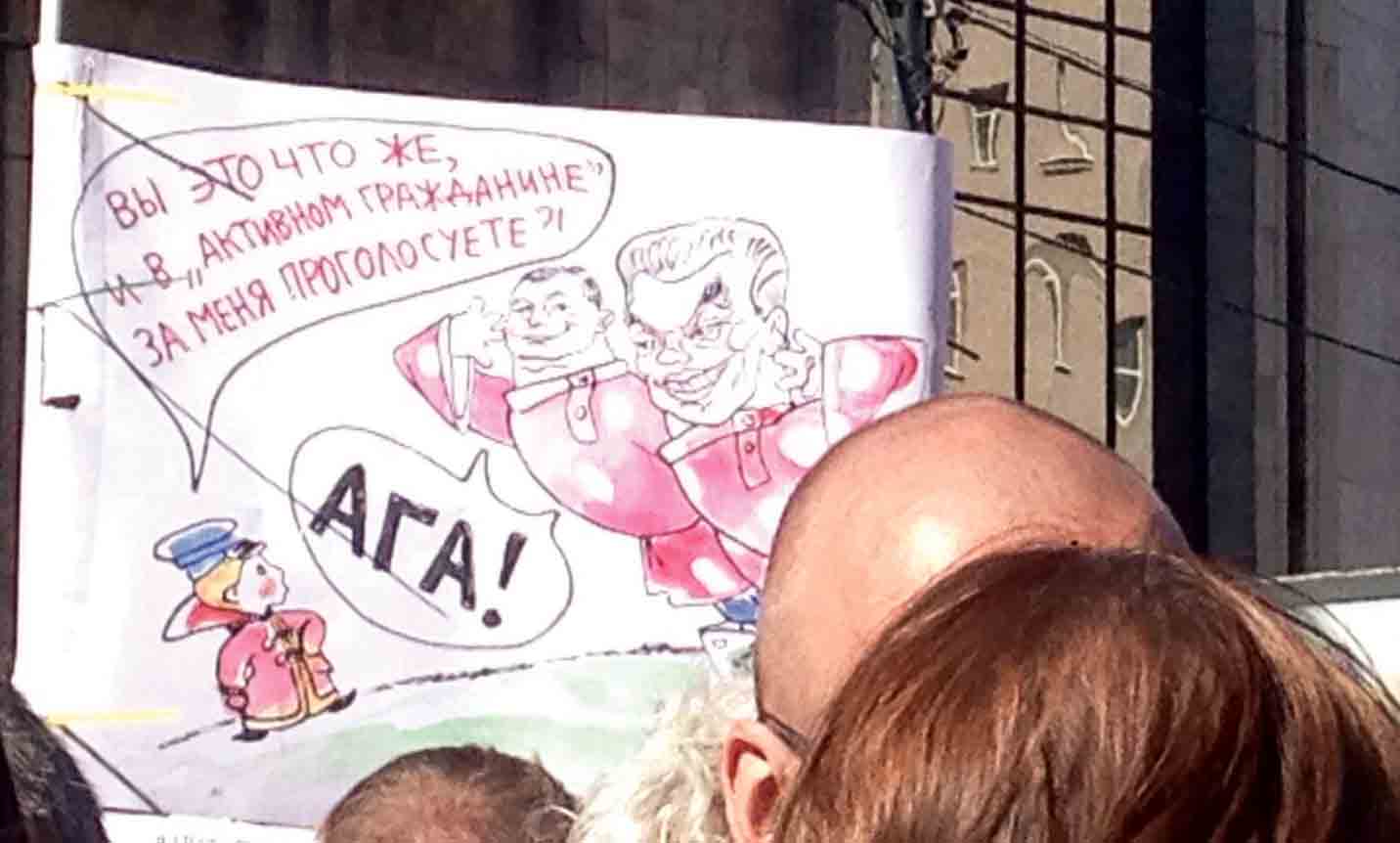

The Moscow City government is attempting to make the process of determining which buildings will be demolished more responsive to citizen concerns. As part of the process, the government is soliciting votes from residents of Khrushchevki to determine whether or not the impacted population supports the initiative. To participate, voters use an online forum established by Mayor Sobyanin’s office called Active Citizen. They must first register and affirm that they are owners and residents of a five-storey house slated for demolition. This otherwise laudable effort to directly engage citizens is significantly undermined by a decision of the Moscow government to automatically count anyone who does not vote in the forum as a supporter, as summarised by the Russian television station NTV: “If you want to vote for the demolition of your five-storey building, you can do nothing at all.” Even if a high percentage of apartment owners participated and voted against, it would be unlikely that this number would outweigh the number of non-participants counted as supporters by default. While the website is entitled Active Citizen, it is likely that the passive citizens will carry this election.

Another problematic element with the online voting system is that it adds even greater uncertainty to the market. Several conflicting official and unofficial lists of houses slated for demolition have circulated. This uncertainty may significantly suppress the value of houses, whether or not they have appeared on an official list. While almost all of the media reports have thus far focused on Khrushchevki, the language of the legislation is sufficiently broad that it could justify demolitions of newer, higher quality Soviet-era apartments constructed during the 1970s and 1980s, or older brick structures that emerged from the pre-Stalin constructivist era.

Many Khrushchevkis today are Soviet on the outside, IKEA on the inside

A society’s desire to preserve architecture reflects its faith in the future intentions of developers, particularly in countries where the rule of law is selectively applied. For example, even when a society is not enamoured by its current cityscape, it may seek to conserve existing structures and/or green space out of fear that what would come in its place would be worse. This is the essential disconnect between supporters of the plan, who are understandably eager to receive a potentially upgraded living situation after so many years spent in a crammed, hastily constructed flat and opponents who believe that the government will not make good on its promises. Reticence to embrace new construction is enhanced by the fact that many residents have witnessed illegal demolitions and blatant zoning code violations in order to accommodate elite new housing that upends the integrity of existing neighbourhoods and strains municipal services.

Meanwhile, the Russian Duma has concluded that any solution to the Khruschev-era housing situation aside from demolition is futile. There are strategies under development elsewhere in the post-Communist world for improving the facades and the overall habitability of existing structures in a way that is far less expensive and socially disruptive than demolishing and rebuilding them. Riga, Latvia, is an example of a city that is currently trying to modify the layout of the micro-rayon to better serve modern conditions.

A joint Dutch-Russian project entitled SVESMI has examined strategies for reinvestment that would be based on demolishing the oldest and lowest quality buildings within the micro-rayon and selling the development rights to build a handful of modern buildings. The new revenue would be used not to demolish the remaining buildings, but rather to rehabilitate the buildings and improve the landscaping, as can be seen in the above before and after artist renderings.

The Ironic Fate of the Khrushchevki

It is a great irony that the Soviet-era apartment, which had long been lampooned by critics as symbolic of the communist government’s attempt to remove individuality and human aesthetics from society, is now defended as a symbol of individual rights and the right to private property. A half century ago, the City of Moscow cleared traditional wooden housing on the city’s outskirts to make space for a sea of grey boxes now known as Khrushchevki. This was the future, Soviet citizens were told. Now the government is eager to erase what it feels are embarrassing remnants of an inglorious past. Despite flaws in the approach, the Russian government should be credited for voicing a principle that all citizens have a right to decent housing. From all indications, the protesters of this action are not on the street based on a shared animus towards the federal or city government. They clearly have an interest in improved housing conditions and aspire to more than 60 sq. m. of living space. Rather, their message to the government this time seems to be: don’t adopt the same one-size-fits-all mentality that led to the original Khrushchevki. Don’t assume that the only thing citizens seek from their neighbourhood is four walls and a nice kitchen. There are ways to systematically improve living conditions; however, for something as intimate as a living space, the burden of supermajority should be on those who seek to demolish rather than those who wish to remain.

(The background for this article is taken from ‘Social Housing with a Human Face: Conserving Moscow’s Soviet Era Housing Legacy,’ in the Routledge Handbook of Global Heritage Conservation, Routledge, 2018.)

Comments (0)