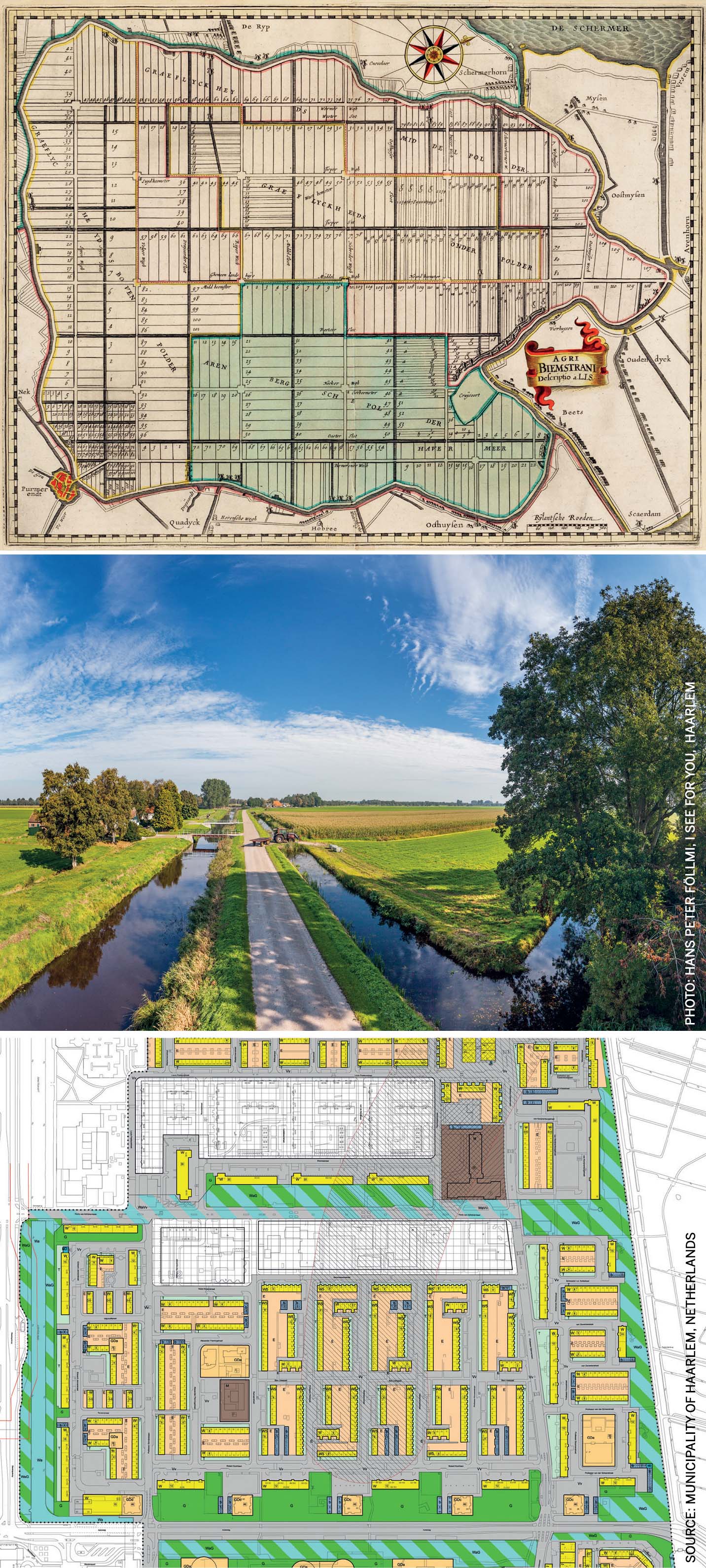

The Netherlands is a small, densely populated river delta along the North Sea coast of Europe, with large areas that lie below sea level. Polders – reclaimed areas surrounded by dikes and drainage canals – allow for intensive use of the rich soil. For ages, water has been a relentless enemy that has been fought with combined and ongoing efforts. From the 13th century onwards this continuing struggle was organised through the so-called Hoogheemraadschappen (high polder boards), the oldest known governing bodies in the Netherlands still in existence. The Hoogheemraadschap was tasked, on behalf of the inhabitants, to make and enforce rules for the water management of the area under its jurisdiction, draining off excess water from the polders being its obvious main responsibilities. This tradition of shared responsibility for proper management of the area has given rise to a comprehensive system of laws, rules and instructions.

One of the consequences of this development is that today virtually every square metre of land has designated and permitted uses laid down for it. Departures are possible, but only after an often long and painstaking process. There are, of course, areas that have evolved in a more or less organic way, but these days there is hardly any room left for spontaneous new uses. Particularly clear examples of this can be found in new housing developments in the Netherlands, where every type of activity has its own place. Even activities that by their very nature are spontaneous and unrestrained can only take place at designated spots. Among the examples are playing areas in public spaces, stretches of grass for walking the dog and zones where outdoor cafés are allowed. In the Netherlands, therefore, there is little room for urban informality, which makes it all the more attractive if, through a fortuitous concurrence of circumstances, it unexpectedly pops up. Let me give you some examples.

Middle: Polder landscape with canal and dike

Bottom: Map of housing development in which every type of activity has its own location

Informality through loopholes in the law

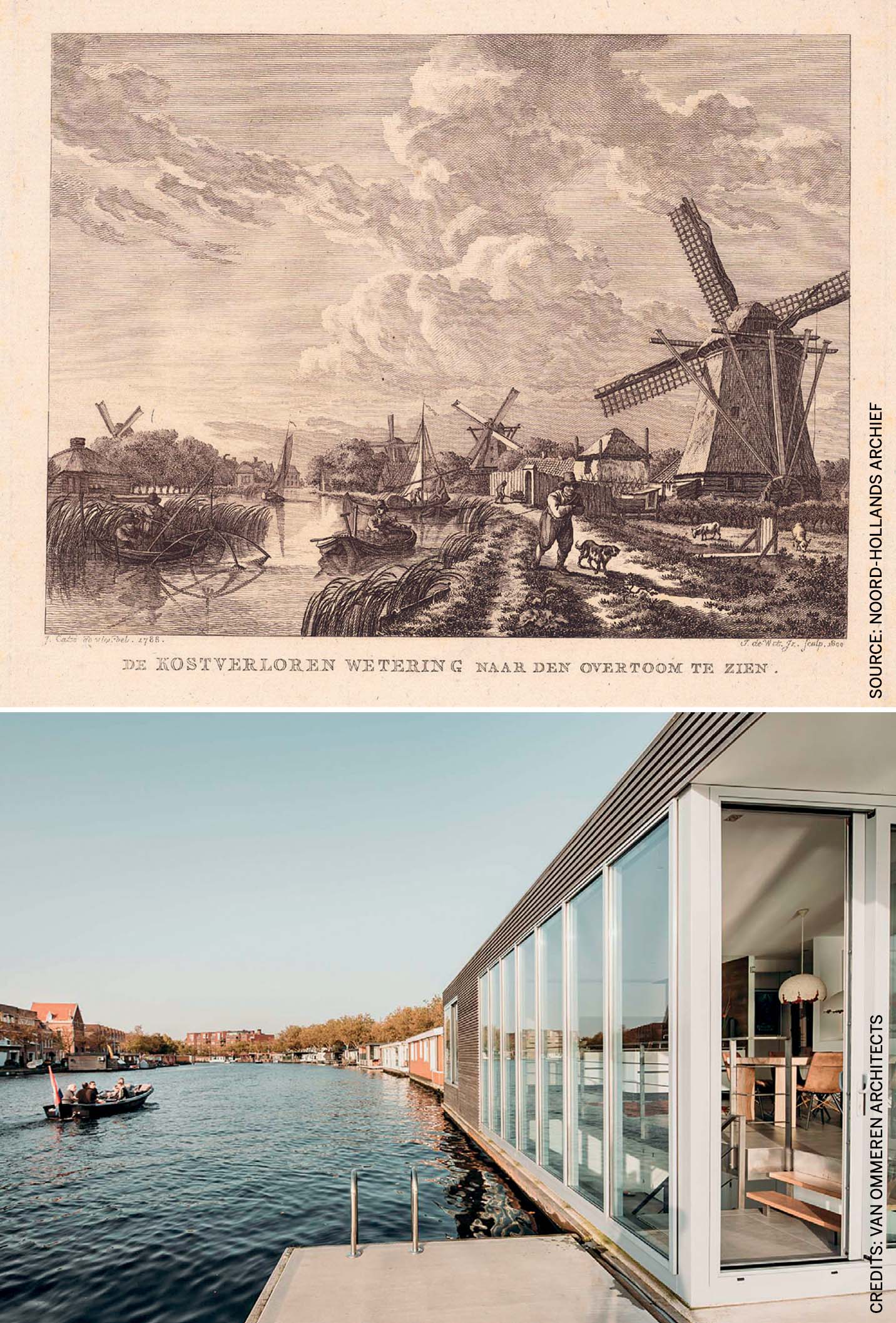

Any truly new and unforeseen development is, at least temporarily, characterised by an absence of rules pertaining to it. A good example is the Jaagpad (towpath) along the calmly meandering river Spaarne in Haarlem. Until the early 20th century, boatmen as well as women who wore a special harness to tow barges and other vessels used these towpaths. Halfway through the century, with road transport becoming more dominant and motorisation of commercial vessels for regular barge service unstoppably on the rise, the path became redundant.

Smaller barges for which motorisation made no economic sense were in many cases laid up or found an informal mooring place where they served as a dwelling place for bargemen and their families or other occupants. The farmer working the adjoining land provided them with drinking water and electricity. It was an arrangement and a situation that was totally unforeseen by regulators. Was the vessel a ship or a house, or both, or neither? In the absence of clear rules, the barge people were intangible to the law and could more or less do as they pleased. Over a number of years the Haarlem city council, out of its responsibility for the wellbeing and safety of all of its inhabitants, and with the intention to put end to the illegal or semi-legal status of this type of housing, came to grips with the situation. In the end, the houseboats were legalised and provided with electricity, natural gas and a connection to the municipal sewage system.

There is little room for urban informality, which makes it all the more attractive if, through a fortuitous concurrence of circumstances, it unexpectedly pops up

Half a century onwards, these mooring places where the barges are gradually giving way to luxurious floating homes, change hands for increasingly large sums of money. What remains is the informal atmosphere, in part because motorised vehicles are still not allowed along the Jaagpad and adjoining agricultural land has not been sold to property developers, but is instead used as a garden by townspeople. Especially in a country like the Netherlands, a seemingly unregulated, idyllic and undesignated strip of land like this is cherished and defended strongly.

A recent example of a new development not yet covered by laws and regulations is the advent of tiny houses. In a time of high prosperity and materialism, many people increasingly feel drawn towards the exact opposite: scaling down to a simpler lifestyle. In the Netherlands, tiny houses have grown into a symbol for minimal, modern and environmentally aware living in unexpected/crazy spots. The Dutch media are rife with images of this ideal concept for living. Local authorities approve of this sustainable concept and announce their willingness to clear the way for tiny houses. In the absence of regulations for this type of small home (smaller than the official minimum for permanent residences), developers have to improvise and come up with charming, more or less spontaneous solutions. Among the first tiny housing sites are industrial estates and yet-to-be-developed building lots.

Meanwhile, work has begun to close regulatory loopholes and bring regulation for tiny houses on par with existing regulations. Which in characteristically thorough Dutch fashion could well result in a mandatory parking slot for each and every newly built tiny house, even if its occupants are bicycle adepts who don’t own or even use a motorised vehicle. Time will tell if the tiny houses ‘movement’ in the Netherlands will really take off. For the time being, it is a freebooter’s dream and a challenge for architects. The predicted boom has so far failed to occur: in the Netherlands, the number of people with a tiny house as their permanent residence has not yet passed the one hundred mark.

Middle: Tiny Tim, an autarkic tiny house

Bottom: Tiny houses as a symbol for minimal, modern and environmentally aware living

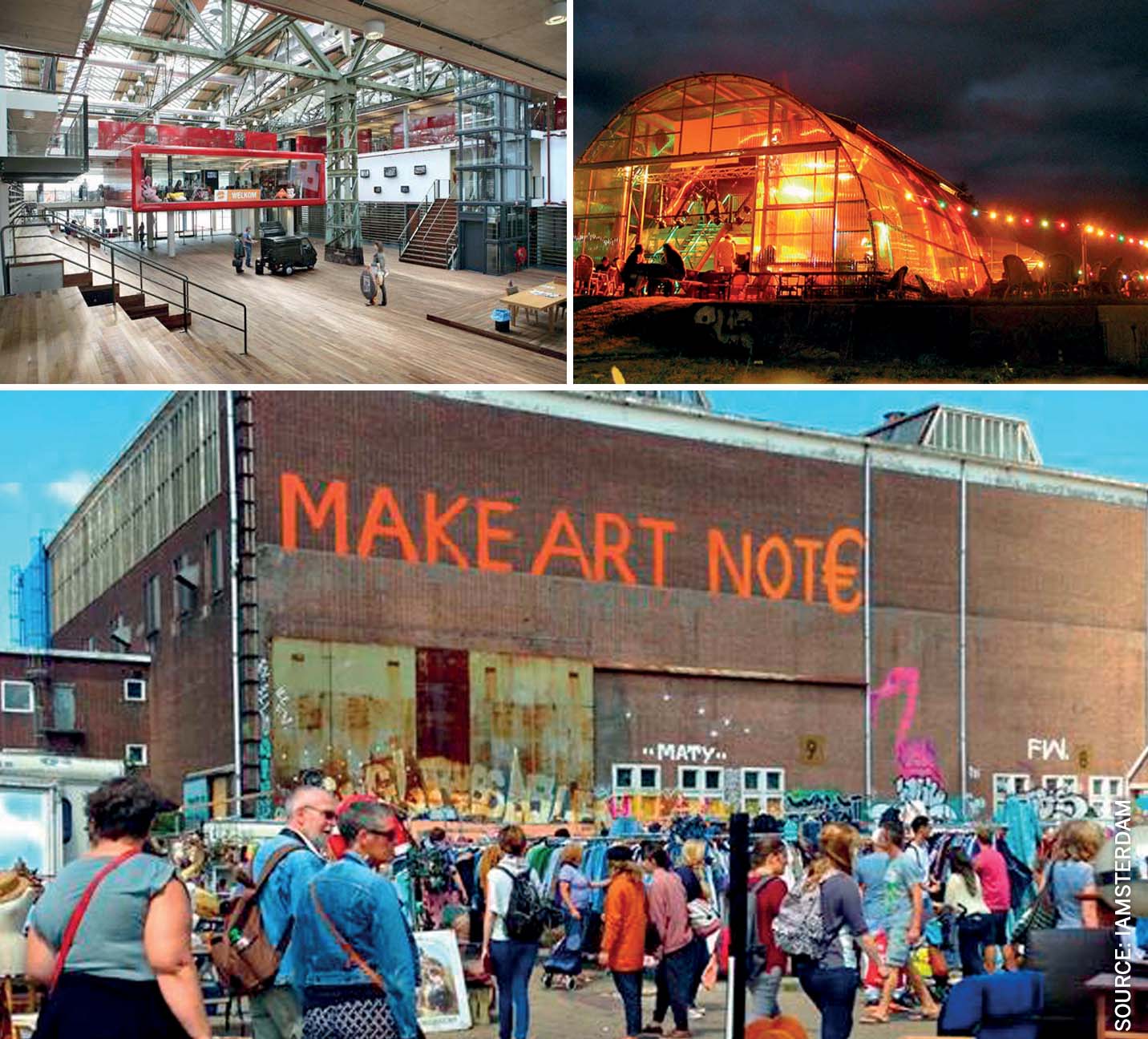

Value creation through informality

Informality is more often seen in interim situations where a temporary relaxation of rules and regulations is more easily accomplished. In adverse times, with low occupancy rates and designated development sites lying unused, there is room for spontaneous actions like urban gardening and horticultural projects, temporary functions and participation projects. If done right, there is limited inconvenience to the owner(s), who may even be better off with property that is in active use, however financially unrewarding it may be. The temporary nature of the situation will mean that investments, and thereby the risk of hard to reverse changes, will stay low.

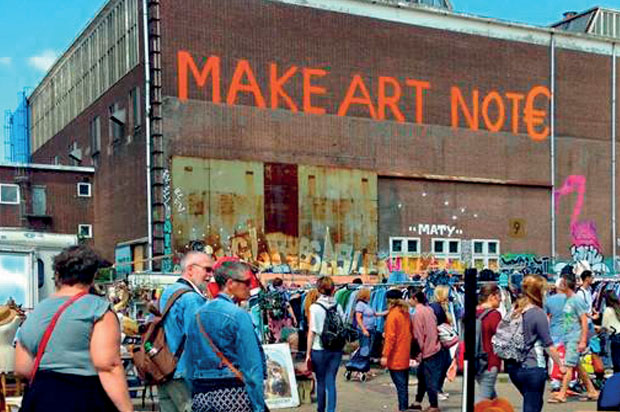

Prime examples are the grounds of shipbuilders NDSM (Nederlandse Dok en Scheepsbouw Maatschappij) in Amsterdam, once home to Amsterdam’s largest shipyard. After the compulsory liquidation of the once thriving company, in the 1980s, the grounds lay largely unused. Virtually from day one, the Amsterdam city council turned a blind eye whenever citizens broke into the unused NDSM-buildings with the intention of squatting and taking residence or setting up shop. These days, the former shipyard is home to a vibrant community of creatives, catering establishments and cultural organisations displaying activities that would otherwise be impossible to unfold in this informal fashion within city boundaries. Once the creation and domain of pioneers, the area has become a powerful attraction not only for tourists, young professionals, start-ups, partygoers and people on a night out, but also for large commercial enterprises eager to create a foothold here.

Tiny houses have grown into a symbol for minimal, modern and environmentally aware living

Meanwhile, a plan has been drafted for high density, mixed use development. Existing factory buildings and squares will be preserved in the design, which seeks to combine the unique informal atmosphere of today with modern, expensive new apartments. The pioneers have, perhaps unwittingly, played their part in the value creation at this post-industrial location. It is not the only example in the Netherlands of a spot where, consciously or not, this effect is being put to use. Allow artists and creatives free rein for a while and the first seeds will be sown. The hard-to-avoid downside is that the newly-built houses on locations such as NDSM are often way too expensive for the erstwhile pioneers themselves, whose only option is to leave in search of the next fringe and the freedom that hopefully comes with it.

A Danish example is Freetown Christiania in Copenhagen. In 1971, hippies moved in to take over and set up home or a shop in barracks and other buildings of this former military enclave. After a period of skirmishes and fruitless attempts by the government to evict the squatters, it was decided to leave the area alone and tolerate the self-proclaimed, more or less anarchist free state as a kind of ongoing social experiment. Entirely without rules and regulations it was not to remain, however, as some forms of entrepreneurship (i.e. the trade in illicit substances and concomitant gang warfare) threatened to run out of control. The enclosed area is now one of the must-see highlights for city trippers from all over the world and can even be called a commercial success.

Bottom: Freetown Christiania in Copenhagen, one of the must-see highlights for citytrippers from all over the world

Leaving more to the inhabitants

The Dutch government shows an increasing interest in urban developments initiated by the city dwellers themselves: the so-called ‘bottom-up’ projects. One of the reasons is that changes conceived by the people will, from the outset, have more support than plans wheeled in by government representatives armed with USB-sticks with tons of slides. This kind of grassroots initiative is often accompanied by a relaxation or suspension of rules and restrictions, thereby making the people involved feel more empowered. Relaxation of regulations for the exterior of houses and other buildings, for example, is becoming increasingly common practice. Future owners and occupants are given more room to choose their own style, according to their own taste, with an increased sense of freedom and ownership as a result.

A concrete example of bottom-up area development is the newly laid out suburban area Oosterwold in Almere. Almere is a new town with over 200,000 inhabitants, situated on Zuidelijk Flevoland, one of the expansive polders in the former Zuyder Zee. The basic concept for Oosterwold is that anyone can purchase a parcel of land and, alone or with others, build their dream house, disco or any other project there. If all goes well, government interference will be close to zero. The Netherlands being the Netherlands, however, some basic rules do apply, such as the restriction that at the most 20% of the plot can be built over, 50% must remain green and environmental regulations have to be met. Already, a wide range of initiatives is under way, turning dreams into reality.

By Dutch standards, Oosterwold is special in the way the local authorities have let go of much of the traditional control and do not know in advance what the end result will be. In a traditionally tightly regulated country, the lure of urban informality is a powerful one. It is therefore expected that more projects of this kind will follow. All this is within the paradox of the recurring wish to regulate the unregulated.

Comments (0)