“There is nothing in all of India to match this long and pleasantest of promenades that runs by the side of the foam-crested surf from the southern extremity of the Fort to Santhome. The Marina is certainly a cap of this ‘city of magnificent distances.” Lavish in her praise, this is what the Irish theosophist Dr. Annie Besant had to say about the Madras Marina.

The Marina Beach is undoubtedly a symbol of the city of Chennai (formerly Madras).Situated on the Coromandel coast, along the Bay of Bengal, it is the longest natural urban beach in India. It stretches over a distance of 6.5 km from Fort St. George in the north to Foreshore Estate in the south. Primarily sandy in terrain, it has an average width of about 300 meters. It attracts about 30,000 visitors daily on a weekday and over the weekends that number could well cross 50,000.

The formation of this beach is an interesting geological phenomenon. Before the 16th century, after the inundations of the land, when the sea retreated, ridges and lagoons would be left behind. When Fort St. George was built in 1640, the sea would wash its ramparts. But when the Madras harbor was being constructed in 1881, the presence of wave breakers laid to facilitate its construction resulted in sand accretion south of the fort on one long muddy ridge, which then was only full of mudskippers. This led to the sea moving 2.5 km away from the fort and the formation of this vast sandy beach.

Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff, Governor of Madras from 1881-1886, was captivated by this pristine beach and built the promenade in 1884 by extensively modifying the terrain and layering it with soft sand. He christened it the Madras Marina, which since then has been the most extensively used public leisure space in Madras.

The social significance of this space for the citizens of this city has been immense: from public rallies during the freedom struggle, to national and state celebrations, from religious festivities to leisure and recreation, from marathons to state funerals.

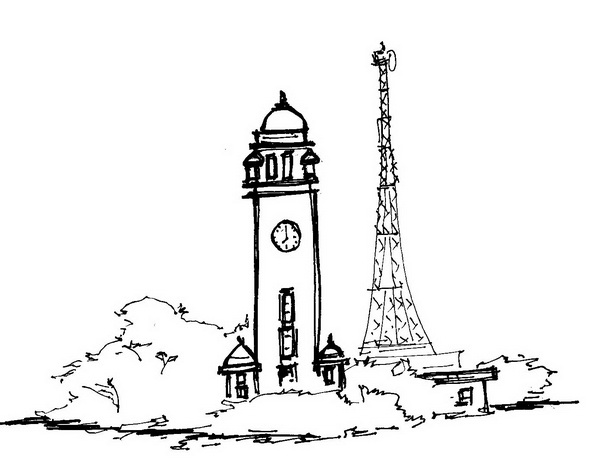

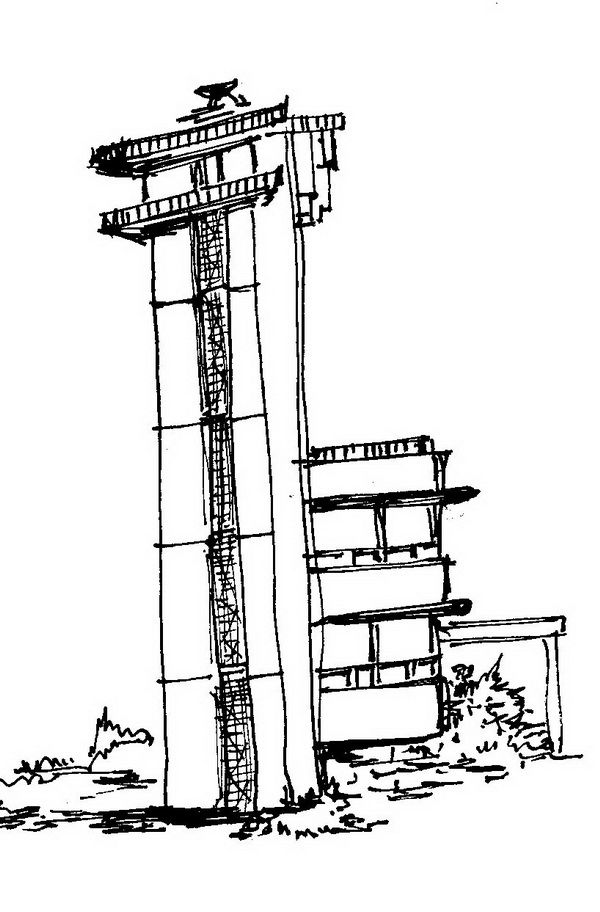

From the end of the 19th century, stately institutional buildings, examples of Indo-British architecture like the University of Madras, Presidency College and Queen Mary’s College were built along the road facing the Marina, each enjoying a breathtaking view of the sea. This enhanced the character of the seafront. In 1909, the country’s first aquarium was built here. After Independence, the first public swimming pool was built opposite the Presidency College, which was bigger than a standard Olympic-sized pool. Another came up later opposite the clock tower of the University. Both provide coaching to the children of the city.

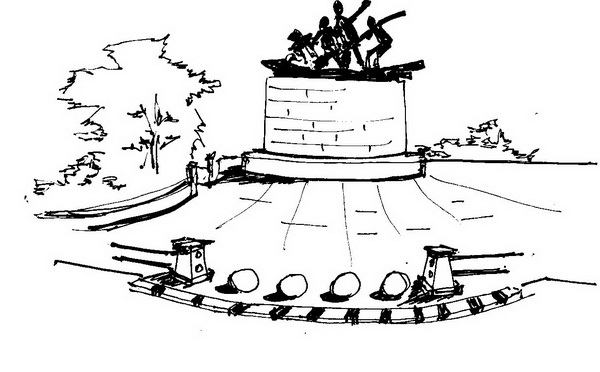

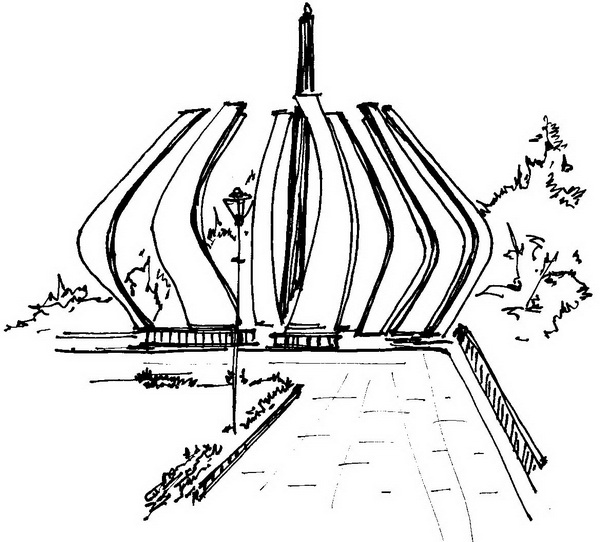

The promenade has an impressive array of statues of luminaries that reflect the sentiment of the city during the period it was built. After Independence, a statue of the ‘Triumph of Labor’ and one of Mahatma Gandhi in a ‘march to Dandi’ stride were amongst the first to be installed. In 1968, the greats of Tamil and English literature were added, reflecting respect for literature in the Tamil tradition. The Anna Memorial came up in 1970 and the one for MG Ramachandran in 1988.

|  |

|  |

The beach has, for a long time, provided the citizens with basic infrastructure like a jogging track, an area for food stalls, a joy ride zone and a cozy lovers’ spot. Kite flying and beach cricket have been the informal sports practiced by many young people of the city. Swimming is prohibited due to dangerous underwater currents. But mishaps do happen, which is why a police patrol has been provided for the beach.

The infrastructure development got a boost when the Chennai Corporation took up major refurbishment of the promenade in 2008. Non-slippery walkways with organized seating, landscape features like plazas, gazebos, pergolas and high mast lighting transformed the 3 km. stretch into 14 galleries each with an element of theatre to it, with stages allowing people to just sit or perform. Architectural elements of the heritage buildings across have been borrowed to maintain homogeneity. An oval skating rink with a protective railing and a dedicated spectator zone has been a recent addition to the sports facilities at the Marina.

A giant chess board and an interactive fountain in the children’s play zone are popular attractions. The ‘Chennai Forever’ initiative set up a 34-feet tall artificial waterfall. Public conveniences include bus shelters, watch towers, rest rooms and five reverse osmosis plants to provide more than 30,000 liters of safe drinking water to the public. The zone has also been declared plastic free.

The Marina Beach has been a source of livelihood to many over the years: for the fishing community, which is present at the two ends of the beach and, in modern times, the vendors who occupy hundreds of stalls for food, merchandise and games. But unfortunately, this once pristine, highly eco-sensitive region has been abused by the public, which has had serious implications on the marine flora and fauna unique to this coast. This nesting site for the migratory Olive Ridley turtle between November and February too has been adversely affected. Fortunately, many voluntary and state organizations have taken up this cause and are working towards waste management and general maintenance of this space.

The tsunami of 2004 destroyed the beach and hundreds of lives were lost. After the tragedy, it took a while for the beach to come back to life. But it did. A space that was conceived about 130 years ago, is still the main getaway spot for millions of residents of a congested Indian metropolis to catch an early morning glimpse of the rising sun, to walk and take in a breath of fresh air, to spend time with family and friends or to just be with oneself.

The city has ambitious plans for the Marina, which include setting up of a world class visitors’ center. A strong political will by the city Corporation and a sense of ownership by the citizens in maintaining the cleanliness of the space can revive the glory of this geographical marvel. The city of Chennai and its people owe it to the Marina.

DRAWINGS: PRITHA SARDESSAI

Comments (0)