One of the most thrilling places to visit in Indonesia today is Jakarta’s M-Bloc. Here, a young generation meets, not only to enjoy leisure time, but to create a new culture and work for social renewal. Where did these dynamics suddenly come from, and where are they headed? These were the central questions addressed during the Workshop ‘Reuse, Redevelop and Design’ jointly held in February 2020 by Jakarta’s Trisakti University and Tarumanagara University, the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands and the Dutch based developer Schipper Bosch. The workshop was part of a larger cooperation programme, aiming for knowledge exchange in heritage management. The challenges of adapting historic structures to current needs is, after all, not restricted by country borders, but is a global topic. For that reason, both countries joined forces to find common solutions. Another article in this issue further elaborates on this cooperation programme.

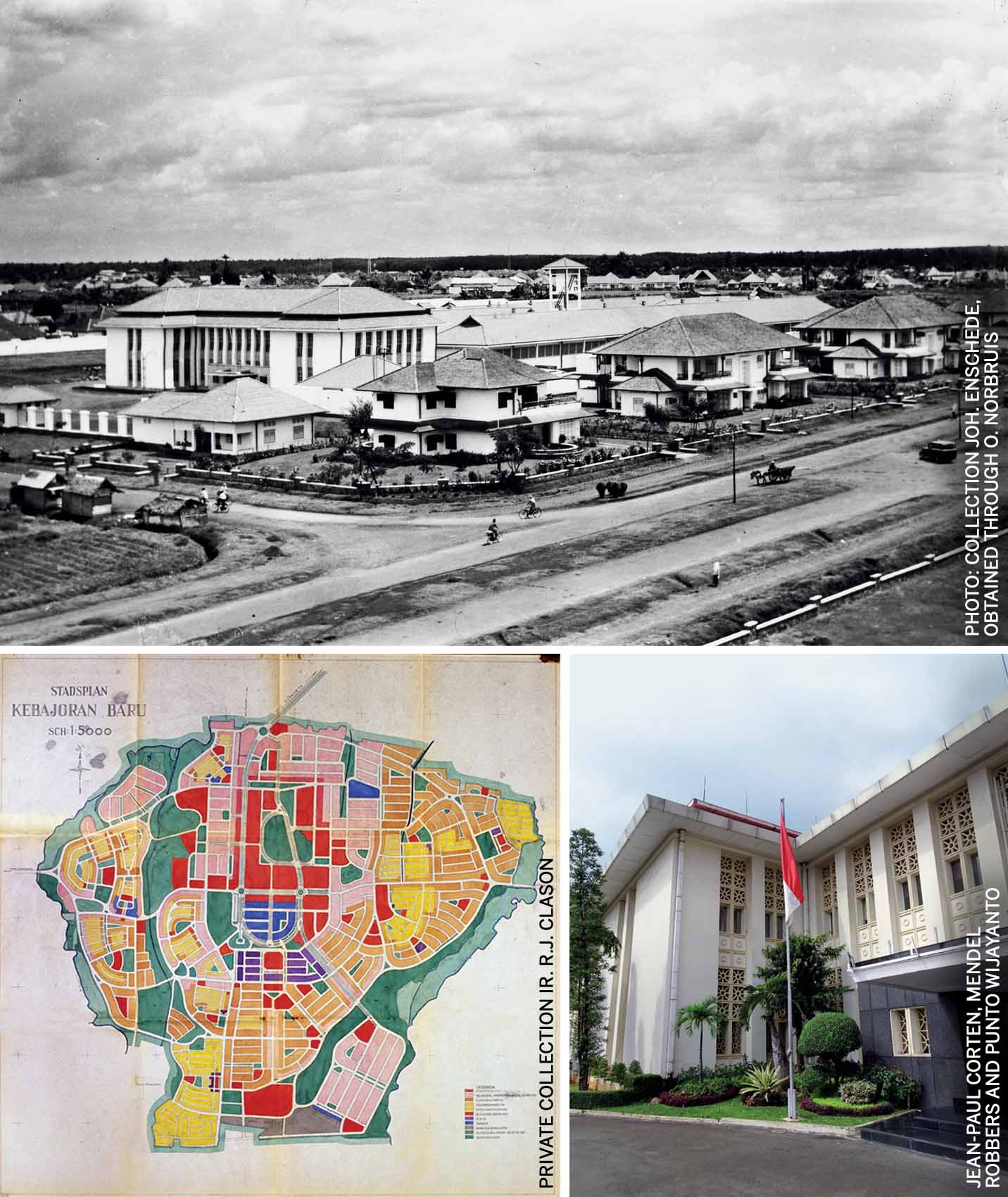

Left: Development Plan for Kebayoran Baru as designed under the leadership of ir. Soesilo in 1948

Right: Current façade of Peruri’s headquarters

Past developments

When on August 11, 1955 Mrs. Rachmi Hatta, wife of Indonesia’s vice-president, conducted the opening ceremony of the Pertjetakan Printworks, the young nation found itself at the forefront of modernity. The new plant was the largest and most up-to-date printworks in the world. Finally, Indonesia had the facility to print its currency on its own soil. The Printworks was located at the very heart of Kebayoran Baru, the latest extension of Jakarta, planned and designed according to current trends.

The modern plant consisted of two parallel assembly halls of some 100 metres each, preceded by a rectangular, two-storey office building with an overhanging roof, in the typical Indonesian Art-Deco style. The design of the representative structures was by the Dutch-based architectural firm Fermont-Cuypers, which had been one of the leading architects in the country during colonial times. Other assembly halls and storage facilities would gradually fill the remaining compound in the coming decades as the company expanded. The entire compound was enclosed on all four sides, to form a safety zone, with dwellings for employees and staff. The two gatehouses flanking the entrance gate at jl. (jalan, or street) Sunan Kalijaga as well as the two-storey dwellings on jl. Trunoyo, were designed by the same architectural office. The remaining dwellings, all constructed in the so-called Yankee-style, were designed by Indonesian architect Moetalib Danoeningrat.

The design and construction of the buildings was strongly influenced by the former coloniser and the public limited company was run by the Dutch-based Joh. Enschede. This firm had already printed the currency used in the Dutch-Indies before independence and was well acquainted with the local situation. Therefore, it was logical to give them the assignment. However, this highlighted the ambiguous position of the self-conscious independent nation, aiming at modernity but depending on its former coloniser for the same.

The workshop was part of a larger cooperation programme, aiming for knowledge exchange in heritage management

This uncertainty was solved in 1958 when the Printworks were nationalised and became a state-owned enterprise. In 1971 the Printworks merged with the coin minting company to become the Percetakan Uang Republik Indonesia (PERURI), producing banknotes, coins and security papers. In 2005, production was relocated to Karawang, leaving only the administrative functions in the huge compound in Jakarta. Thus, large parts of the complex became redundant along with most of its staff dwellings. The once industrious heart of Kebayoran Baru now has to redefine its position, offering great opportunities to accommodate the current needs of a developing society.

The development of Kebayoran Baru was rooted in a colonial past. First plans for the extension of the fast-developing metropole date back to 1937. Execution of the plans started under Dutch rule, but only took off after transfer of sovereignty in 1949. The new country’s Ministry of Public Works took responsibility for conducting the strictly centralised works, under the leadership of ir. Soesilo, who had been involved in the planning since the 1940s. The design of the new extension was largely based on Dutch ideals of the garden city, following the example of Menteng. Large boulevards of green formed the backbone of the multifunctional city quarter, which would house both higher and lower income groups. At the same time, it had to accommodate work facilities, commercial functions and public services. This self-sufficiency of the new city quarter aimed at bringing relief to the overwhelmingly growing traffic in the capital city. The spacious plans offered opportunities for future adaptation, development or growth.

Soon after completion, adaptation became paramount. Jakarta’s population grew much faster than anticipated and Kebaroyan Baru was soon encircled by new city quarters. The once peripheral city quarter became the central hotspot of an ever-expanding metropole. Due to this newly acquired position, and its well-designed connection to the rest of the city, development pressure quickly increased. To bring relief to the pressing development needs, the former central planning principles of Soesilo were abandoned in the 1980s and public land was transferred to private developers. Many shopping malls and luxury apartment blocks came up, obstructing balanced development and flagging urban quality. On a planning level, the main challenge for the new development of the Peruri site was to restore balanced growth and the urban qualities of the modernist plan.

Bottom: The ‘Peruri 88’ proposal by MVRDV and Wijiya Karya

Current situation

In 2012, a first proposal for redevelopment of the Peruri site was drafted, named ‘Peruri 88’. The proposal, prepared with support from the reputable Dutch architectural firm MVRDV, presented a vertical city of 88 floors and

360,000 m2 consisting of mixed-use development including luxury housing, offices and commercial space as well as internal and external public spaces. The plan is in line with the privatisation which started in the 1980s and it takes full advantage of the strategic location. Already in Soesilo’s masterplan, Blok M, the central part of Kebayoran Baru where the Peruri site is located, was envisioned as the transportation and transfer hub. Today, with the first phase of the Mass Transit Rapid (MTR) Jakarta inaugurated in 2019, Blok M may be the most accessible location in the entire country. The Peruri site has two metro stations located within six-minutes walking distance.

Awaiting further debate and final decision on its future development, in 2019 Peruri offered an opportunity to a group of creative people to use their properties for cultural activities, as a means of placemaking. This creative community of artists, architects, branding consultants, etc. has taken on the ambitious task of supporting local products and local communities. They try to achieve this goal by re-programming the existing structures for cultural gatherings, social meetings and the purchase of local products. The new name for the place is ‘M-Bloc’, referring to Blok M in Soesilo’s Master Plan for Kebayoran Baru. In the 1980s, Blok M attracted youngsters; M-Bloc consequently targets millennials.

The challenges of adapting historic structures to current needs is not restricted by country borders

Peruri allowed the use of 6,500 m2 of land, which consists of 16 units of two-storey ex-residential dwellings along jl. Panglima Polim and a former printing warehouse. The front row of buildings is for food and beverage shops and for creative stores. The former printing warehouse is now used for music concerts and restaurants. People visiting M-Bloc can also enjoy outdoor activities in the so called ‘brandgang area’, the open space connecting the two parts. This popular place is always crowded, especially when a concert is on.

M-Bloc is an outstanding example of giving temporary use to old structures as a means of placemaking, which is currently a topical strategy in urban development. This is never a lasting solution, but it offers opportunities to debate a sustainable future. The four partners instrumental in establishing M-bloc jointly organised a workshop to analyse the future potential of the existing structures of the Peruri complex.

Middle: Participants of the workshop ‘Reuse, Redevelop and Design’ in front of the current Peruri headquarters

Bottom: Participants of the workshop doing fieldwork at the Peruri site

Future perspectives

The workshop ‘Reuse, Redevelop and Design’, held from February 3-7, 2020, aimed at defining alternatives for the Peruri 88 concept, building upon the historic features of the site and the city quarter, while maintaining its current use. Most of the 16 participants of the workshop were master students and some were young professionals. During the workshop, input was provided by experts like Jacob Gatot Surarjo, architect and co-founder of M Bloc Space, representative of the Ministry of Education and Culture, the Pusat Dokumentasi Arsitektur, PT MRT and also representative of Jakarta’s Human Settlement, Spatial Planning and Land Issue Agency. The results of the workshop were presented at the Erasmus Huis, the cultural centre of the Netherlands in Jakarta.

The first observation made at the workshop was the planning paradox in the recent history of the Peruri site. The planning of the eye-catching Peruri 88 in 2012 attracted the attention of the international architectural press. Following this planning brainstorming, M-Bloc was constructed on the site. The contrast could not have been more glaring. Peruri 88 had ignored the existing, while M-Bloc embraced what was already there. This is illustrative for the spatial planning discipline that currently stands at a crossroads: Tabula Rasa (starting afresh) versus Tabula Scripta (building upon the existing).

The fundamental question was: How to deal with divisive social segregation and developments that are increasingly vulnerable to gentrification?

Professionals have an understandable urge to exclude as many restrictive conditions and complexities as possible from their projects. The goal of the workshop was to build upon the existing and work with it’s complexity. The workshop stimulated the participants to be part of an interplay of a wildfire of forces that can only be controlled to a very limited extent. The participants were urged to better observe and better reflect, in order to tap into a different and more relevant form of creativity. One that goes beyond spatial, aesthetic solutions. The stratification-strategy included historic, spatial, programmatic and social dimensions, as well as understanding that the ultimate form of doing the right thing first and foremost lies in observation and reflection. The 16 participants of different professional backgrounds were divided into four groups to ensure the complexity of collaboration. Undoubtedly, the ability to join forces in many different settings defines the success of working with such a strategy as a professional.

Within a week, each group had to come up with a proposal that contained both thorough analysis of the site and a set of possible interventions in software and hardware. The participants of the workshop carefully worked around M-Bloc and spent much time working with the available information on the boundaries, the interfaces between them and how and where people fit in. New insights were incorporated into the programme and novel spatial solutions were introduced, carefully situated next to, in or on top of existing buildings. It is notable that none of the groups opposed the value of the existing buildings nor the position of M-Bloc, and perceived it as a permanent asset for the area. All efforts were made to turn the area into an even more successful hub of new businesses and public-used spaces with a vital, entrepreneurial and cultural character.

Bottom: New Section and Elevation of Peruri - One of the four student proposals for the redevelopment of the Peruri site

Professionals have an understandable urge to exclude as many restrictive conditions and complexities from their projects as possible

Towards a stratification strategy

The workshop proved that the efforts of M-Bloc to attract people back into the existing buildings on the site were appreciated and was seen as a motivating power for future plans. All groups agreed that the site should attract a more diverse group of people and posed the fundamental question: How to deal with divisive social segregation and developments that are increasingly vulnerable to gentrification?This proved that taking the broader view enriches the professionals and takes them beyond their spatial design expertise. It also proves that working with the existing doesn’t mean that it can’t be debated or adjusted.

During the final presentation at the Erasmus Huis, it was concluded that although the workshop did not come up with the ultimate re-development plan for the Peruri site, it does show a way forward in finding a sustainable future for the site. A stratification strategy, including a holistic analysis of interests and needs will tap into the potentials and qualities that already exist. Thus the site is no longer perceived as an empty sheet but as a written page, offering social and economic relevance and options for creativity.

Comments (0)