Ladakh is a cultural and climatic region in a remote part of North India. Located at the intersection of Central-Asia on the west, Tibet on the east and the Indian peninsula on the south, the region of Ladakh is historically significant for trade and cultural exchanges. Although Ladakh is a melting pot of cultures, the influence of Tibetan elements is more pronounced. Which is why it is also called a microcosm of Tibet in India.

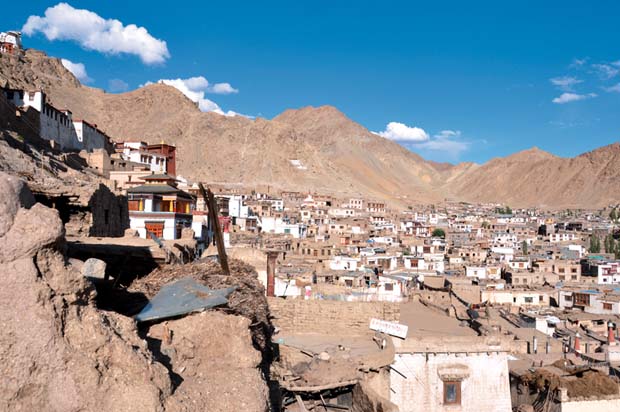

Unlike most Himalayan ranges that are green and receive significant precipitation, Ladakh is distinct for its cold and dry desert climate. The landscape of Ladakh is characterised by ranges of barren mountains punctuated by imposing monasteries strategically placed along the trade routes. These monasteries are located high on the hills and often accompany settlements located down the slope. This settlement pattern was primarily to provide protection against attacks from invaders and also to gain sunlight for an extended period of time. While the region is very arid, the streams bring water down the glaciers and create oases for the cultivation of paddy and vegetables. Apple and apricot are the main plantations among fruits. Also, the plantation of poplar trees – the main source of timber in the region – has increased in recent years. The sepia background is contrasted by the colourful Tibetan prayer flags and white painted mini stupas called chorten found all over. The general ensemble of landscape elements in Ladakh offers an exceptionally mystical, surreal and exotic scenery to the visitor.

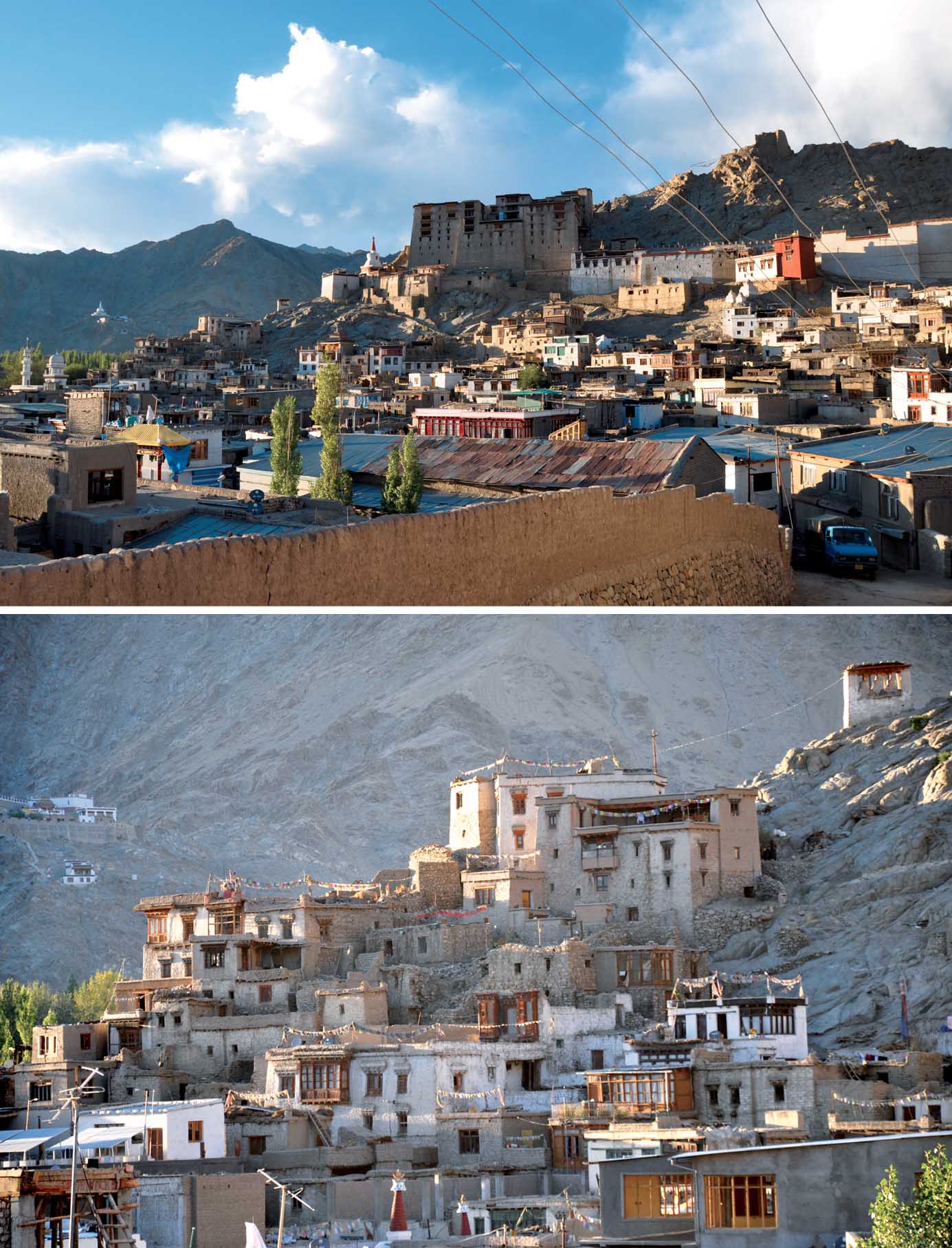

Bottom: Urbanscape showing exquisite mud architecture of Old Town Leh

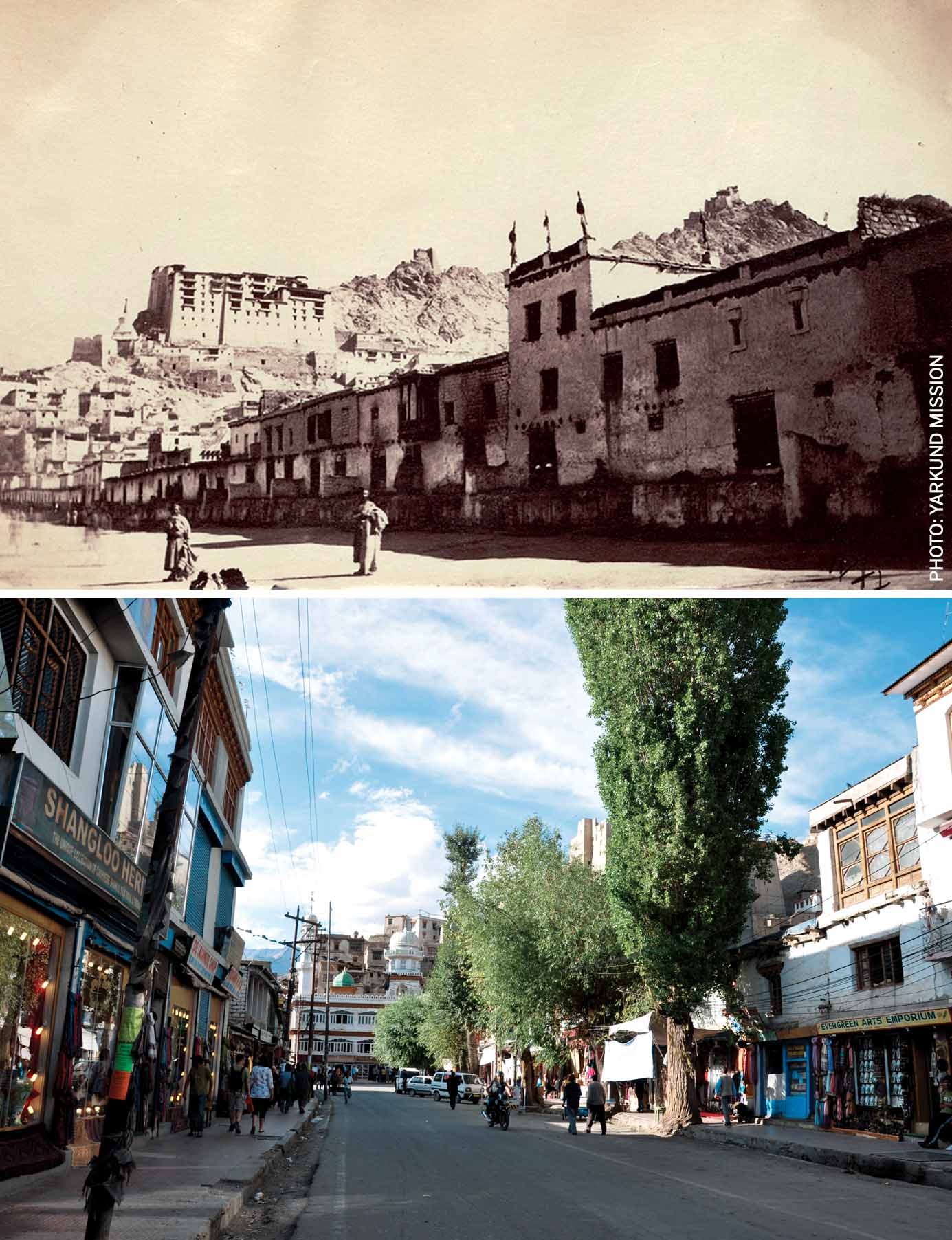

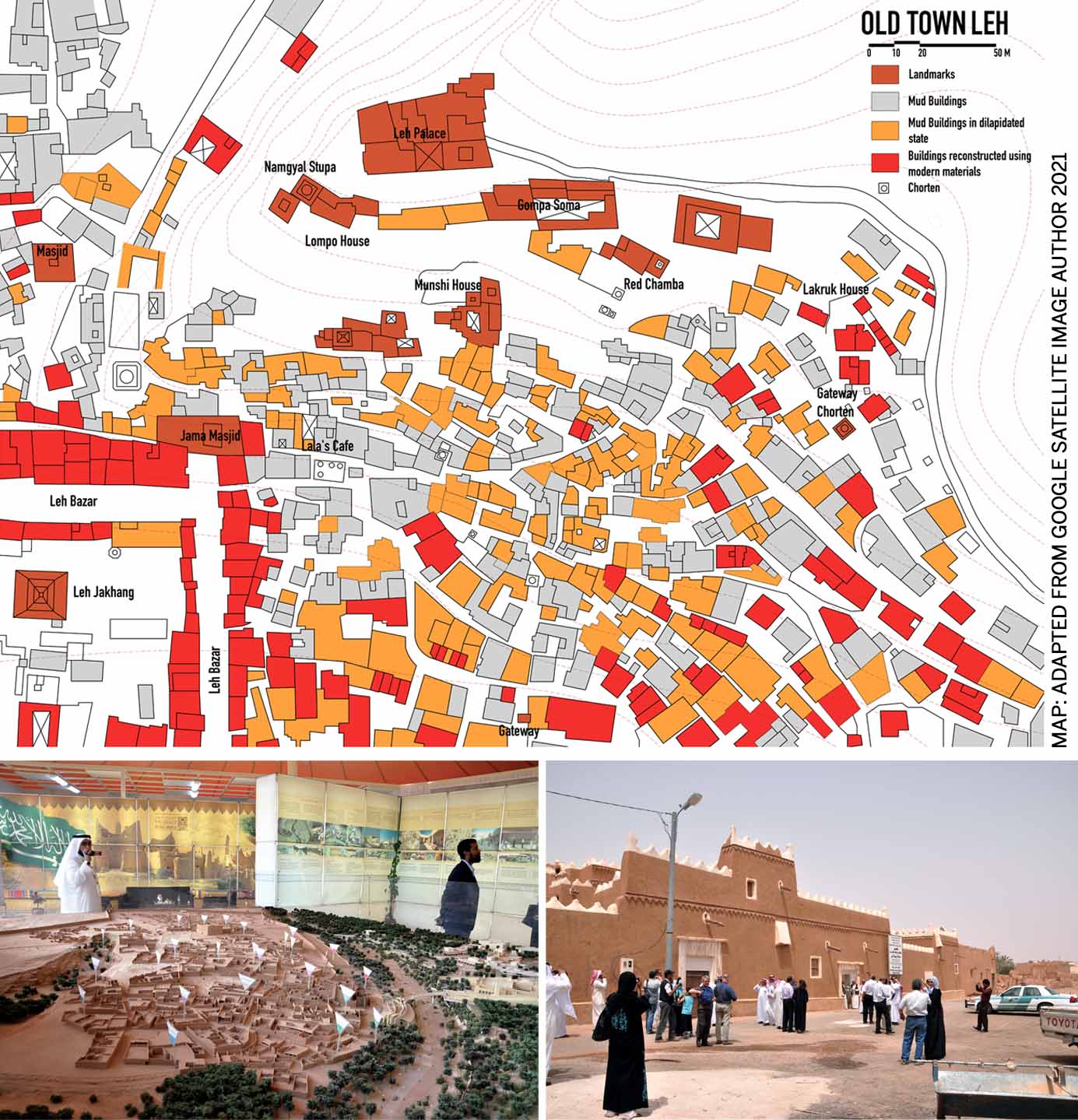

Leh is the principal town of Ladakh, located on the junction of major trade routes connecting Srinagar, Lhasa and Manali. Leh emerged as a major trade and cultural destination soon after King Senge Namgyal shifted his capital from the neighbouring Shey in the early 17th century. The king marked the new capital by building an imposing nine-storey palace, which was the tallest structure in Ladakh and Tibet until Potala Palace was built in Lhasa. The setting of the palace follows the spatial hierarchy as seen in the Ladakhi settlements. On the peak of the Namgyal Hill is Tsemo Gompa followed by the Leh Palace, which is located mid-way on the slopes. Below the palace are the monasteries and mansions of the important nobles while the houses of the common populace are located on the lower slopes. Since the town is built on the slope, the settlement pattern exhibits a compact arrangement of built fabric with meandering streets. The intersections of these streets function as public spaces and are marked by the presence of the chorten stupas, the most prominent being called Gateway Chorten due to its portal-like form.

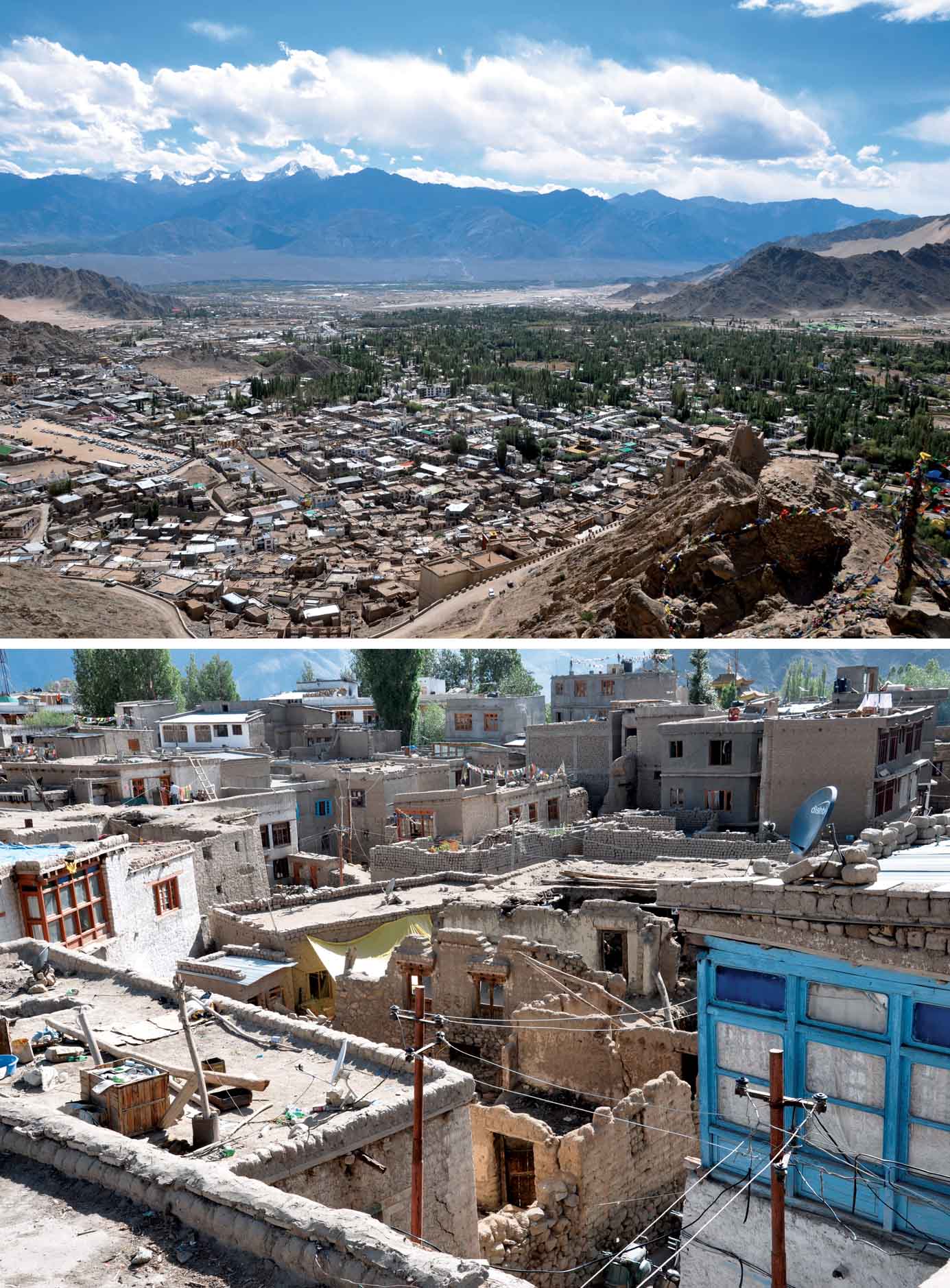

In the absence of any such formal initiative, the town is changing fast, over-tourism being the main catalyst

The core area of Leh constitutes the Leh Palace and the settlement down the Namgyal Hill as described above. The main commercial area, called Leh Bazar, adjoins the core area on the western side as wide and straight market streets meeting at the Jama Masjid junction. The form and arrangement of buildings and spaces in Old Town Leh were dictated by the principle to provide protection against invasions. Earlier, the old town was surrounded by a rammed earth fortification that can still be identified by the presence of gateway chortens. Buildings were spaced out allowing uninterrupted sunlight in cold climatic conditions.

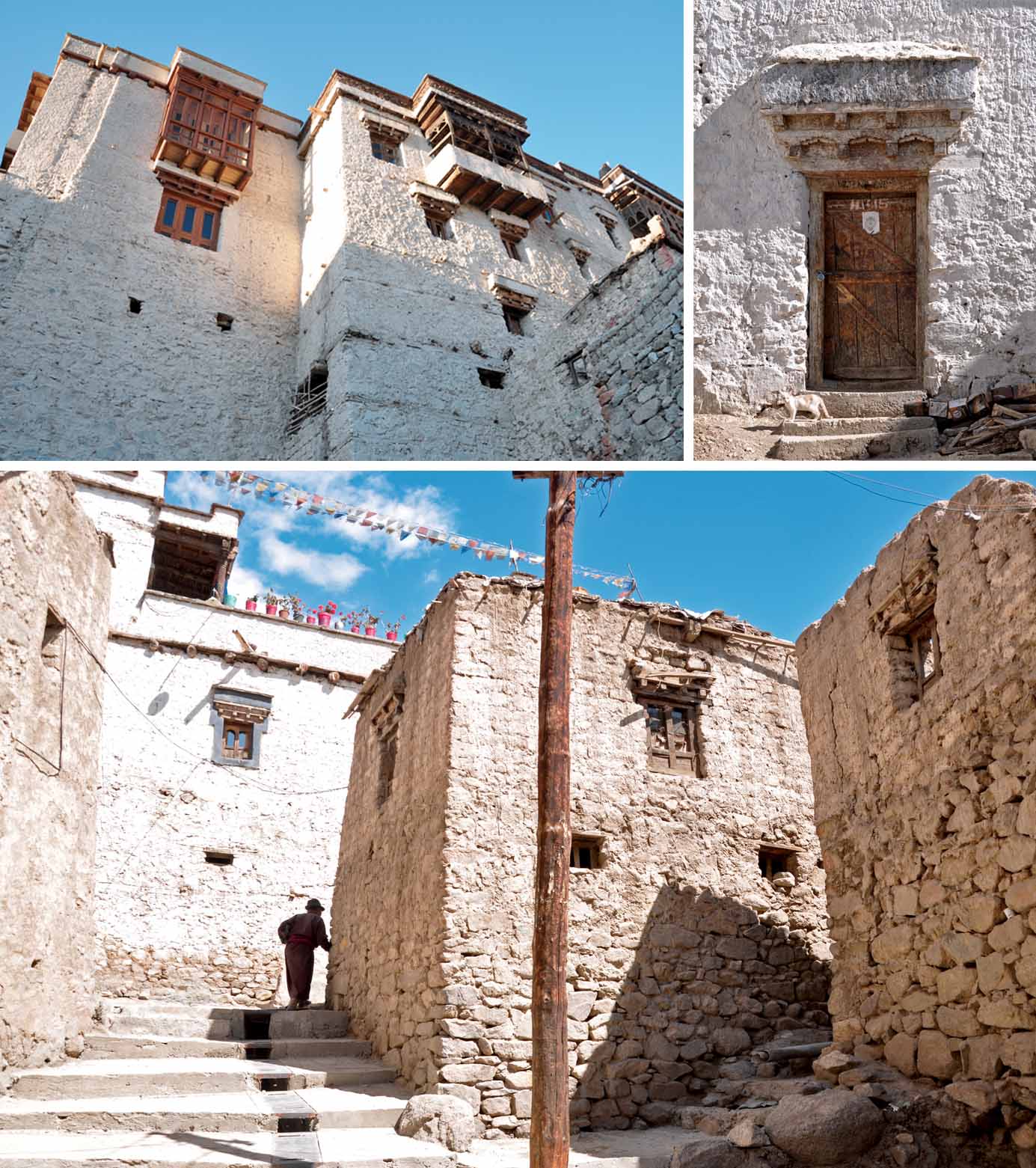

The architecture of Old Town Leh is characterised by remarkable mud construction employing Tibetan elements. The walls are constructed primarily using adobe bricks and rammed earth. Foundation and plinth levels are often constructed in rubble masonry using locally available stone. Timber is used for spanning the roofs and lintels. Window openings are accentuated by frames and projected lintels imparting Tibetan character to the town. Every building has one characteristic large window facing the sun and identifying the living space. Spatially, living room and kitchen are combined in a single large space, which is located on the upper floor, while the lower floor is used for keeping animals and storage. Courtyards are also present in larger houses. Temples are painted in a distinct red colour, monasteries are painted in white and ordinary residential buildings are plastered in mud or painted white.

Top Right: Entrance to an ordinary house in Leh with typical Tibetan lintel

Below: An ordinary house in Leh showing stone masonry at lower level and adobe bricks at upper level

The architecture of Leh is an illustration of extremely refined Ladakhi traditions, which evolved over many centuries using local materials imparting exceptional climatic comfort, durability and a distinct character to the town. Moreover, this is the only instance of multi-storeyed mud architecture in India which is comparable to the World Heritage Sites of Shibam in Yemen, Bam in Iran and Diriyah in Saudi Arabia in scale and architectural richness. Needless to say, these attributes make Leh an ideal case for urban conservation. However, in the absence of any such formal initiative, the town is changing fast, over-tourism being the main catalyst.

Due to its proximity to the border, the entry into Ladakh was restricted until 1974. Even now, the region remains disconnected from the rest of the country during the entire winter season. This inaccessibility, in fact, helped in preserving the tradition and culture until circa 2000. After that, tourism in Ladakh started to witness an exponential rise. This was due to its depiction in the popular movie 3 Idiots as well as by the Government of India’s special LTC package for its employees. Presently, the tourists in the peak season outnumber the native population by three to four times.

Many old mud houses were demolished to construct guest houses and hotels using modern materials and amenities

While this rise in the tourism industry brought economic growth to the region, it adversely impacted the architecture of Leh. Because of poor infrastructure and water scarcity, the population from Leh started shifting to the agricultural fields on the western fringe. As there were no more threats from invaders, the dwellers of the old town preferred living in houses built in the open agricultural fields with streams of water flowing nearby. This rendered the old town irrelevant to the people and the mud buildings started to crumble over time.

The market area of the old town continued to function, but saw transformations in the buildings. The characteristic mud and timber structures were replaced with two- to three-storey brick and concrete buildings housing cafes, restaurants, emporiums, souvenir shops etc. for the tourists. At the same time, guest houses and hotels started to emerge on the outskirts of the town and many in the agricultural fields where the people have already shifted. The owners of the agricultural fields found running guest houses a lucrative and easy business, though they continued growing vegetables and paddy in the open portions. These guest houses and hotels are built using concrete with modern amenities to suit tourists.

Bottom: Abandoned buildings of Old Town Leh

Bottom: Main Bazaar in Leh showing modern transformations

During the same period, the parts of the core area of the old town continued to remain abandoned with mud houses turning into ruins due to neglect. Many of these houses were demolished to function as godowns and tenements to rent out to the migrant labourers who come every year in the summer months to work mainly in the construction industry. Overall, the phase after the year 2000 marked the beginning of the loss of historic fabric in the old town.

Around 2005, the arrival of tourists encouraged some local inhabitants to start tourism-related businesses. This brought about positive changes in the area. The biggest contribution has been by an international organisation called Tibetan Heritage Fund (THF), which carried out conservation of some houses under the Leh Old Town Initiative (LOTI). One of the prominent examples is Lala’s Cafe that is run in a restored house and serves local delicacies. Another example is the restoration of Munshi House by Ladakh Arts and Media Organisation (LAMO) into a gallery and interpretation centre.

The adaptive reuse model is commonly seen in the historic cities of Europe and is considered an effective urban regeneration strategy

However, these projects remained prototypical and the conservation initiatives did not spread to the rest of the old town. With further increase in tourism after 2010, extreme transformations were witnessed. Many old mud houses were demolished to construct guest houses and hotels using modern materials and amenities. They are typically three- to four-storeyed high and look alien to the urbanscape of the old town.

Until the year 2010, THF listed around 200 buildings in the old town that illustrate mud architecture. Out of those only 25% of the buildings were in a habitable state while around 50% were in various stages of decay. Given the situation, in 2008 the World Monument Fund (WMF) declared Old Town Leh among the 100 most endangered sites. The loss of mud buildings in the old town is a permanent loss of Ladakhi architectural and urban heritage. It is also counterproductive to tourism as the old town in itself has the potential to act as the main tourism resource.

Top Right: Lala’s Cafe. An example of community-led reuse of a mud house in Old Town Leh

Bottom Left: Munshi House after Adaptive Reuse by LAMO

Bottom Right: Restoration of Sofi House by THF under architect Andre Alexander

While it is clear that Old Town Leh is an important and irreplaceable urban heritage asset, it can also be seen from the discussion so far that piecemeal projects of restorative conservation are not adequate for the regeneration of the entire old town, which will require formulation of a comprehensive plan. While funding for the infrastructure upgradation like street paving, water supply and sanitation is usually available through various national and local sources, there are very limited funding provisions for the houses because they are privately owned.

One of the urban regeneration models commonly used in such a situation is Adaptive Reuse, which goes beyond the idea of restoration and works on the principles of circular economy and urban recycling. Since these houses are abandoned, they have lost their relevance as residential property resulting in their demolition and construction of new buildings that generate income. In adaptive reuse, the same houses can be repurposed by restoring their architectural characteristics, upgrading them with modern amenities and even expanding the space using compatible architecture. While the new function introduced to these houses generates revenue to compensate for the restoration costs, it also facilitates the regular maintenance unlike vanity restoration projects. Successful similar examples of adaptive reuse of mud towns are Diriyah, Al Majmaah in Saudi Arabia and Bastakia in Dubai. In India, Fort Kochi and Fontainhas in Panjim are examples of settlement-level adaptive reuse.

Bottom Left: Diriyah mud town regeneration plan

Bottom Right: Al Majmaah town in Saudi Arabia restored and adaptively reused as a tourist site

For the entire scale of Old Town Leh, a comprehensive plan will need to be prepared starting with inventorying the abandoned houses, which will have to be earmarked for new functions based on their locations and spatial layouts. The essence of adaptive reuse at settlement scale lies in providing wide-ranging functions like cafes, restaurants, guesthouses, hotels, galleries, souvenir shops, emporiums, craft workshops, museums etc. This variation in the function breaks the monotony in the tourist experience and results in inter-related economic activities complementing one another.

The adaptive reuse model is commonly seen in the historic cities of Europe and is considered an effective urban regeneration strategy. In India, urban regeneration is in its infancy and adaptive reuse is carried out as solitary projects. However, Old Town Leh being the last example of a Tibetan town, after Lhasa has been heavily redeveloped, needs to be salvaged immediately and regenerated by employing the adaptive reuse model. In the case of Leh, adaptive reuse is the only model that holds the potential of dovetailing the regeneration of the old town with tourism and economic development.

All photos: Author

Comments (0)