Auroville is a self-governing, international township located 5 kms off the coast of the Bay of Bengal. Recognised by UNESCO as an ‘international cultural township’, it is known for being a work-in-progress social experiment, and a full scale town planning model that places ecological urbanism at the forefront. While it falls under the jurisdiction of the central government of India, it has been given a degree of autonomy, such that anyone from around the world can apply to be a part of it. Its 3,300 residents, who hail from 60 different nationalities, describe themselves as being committed to working towards the utopian dream of “divine consciousness for all”, which was set in place by Auroville’s founder Mirra Alfassa (better known to her followers as The Mother), the French disciple of the Indian nationalist and spiritual guru Sri Aurobindo. Yet alongside this spiritual mission, the township is noted for its experiments in education, green building technology and economics, attracting students and volunteers from within India, as well as Europe, Russia and America. People come here to participate in hands-on sustainability workshops, study spiritual teachings or simply to get a feel of the place.

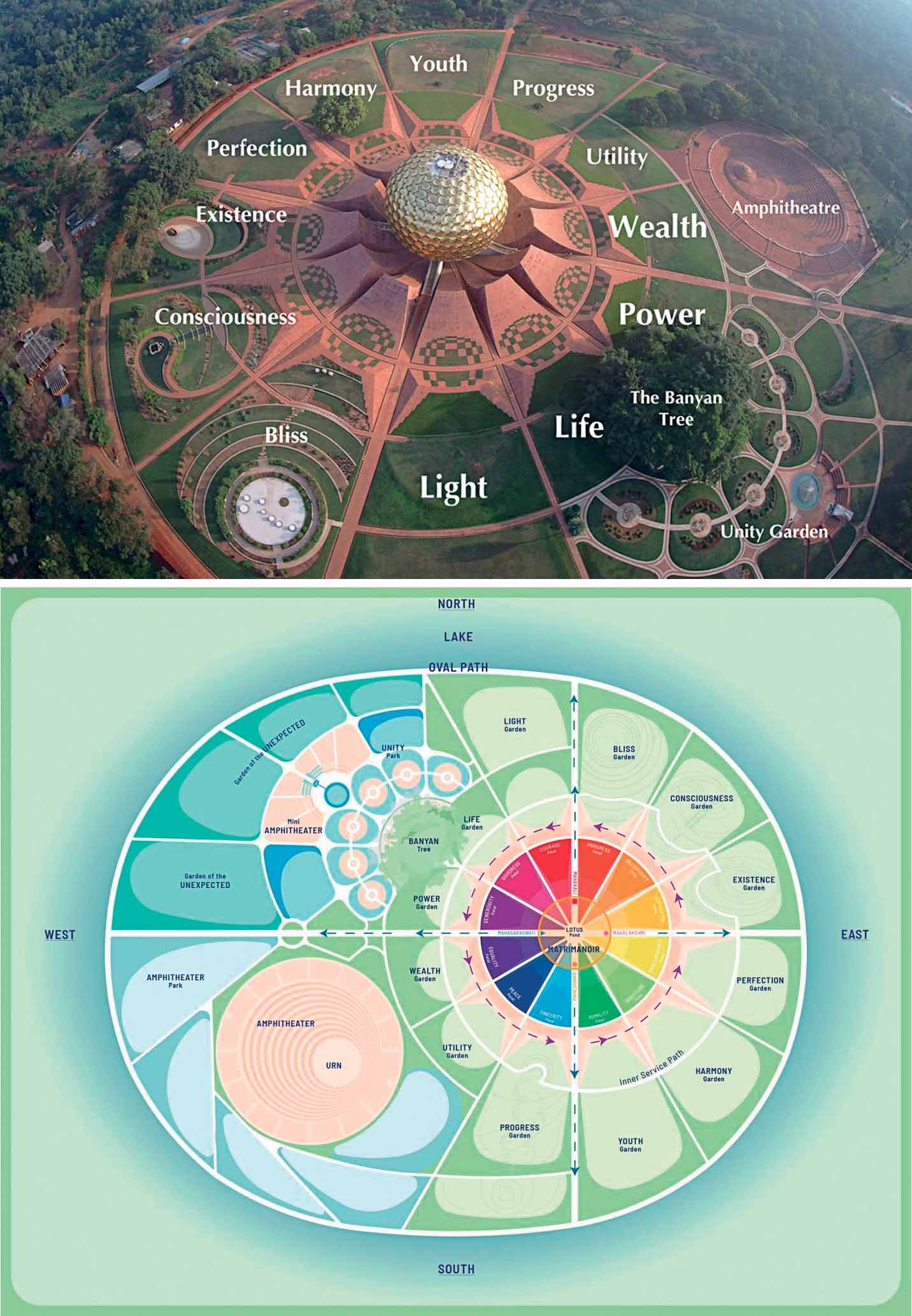

“Auroville will be the place of an unending education, of constant progress, and a youth that never ages.” These words were read out on February 28, 1968 as representatives of 124 nations and all states of India placed handfuls of earth from their homelands into a marble-clad urn to symbolise human unity – the stated purpose behind the birth of Auroville. More than 5,000 people gathered on inauguration day at the amphitheatre that had been built along with Matrimandir (the Temple of The Mother) in what was to become the central core of the township, now known as the Peace Area. The Peace Area also contains 12 main gardens around Matrimandir (which are in varying stages of completion), peripheral green spaces and a surrounding lake, all planned by the late French architect Roger Anger, who had been appointed by The Mother to oversee the physical development of Auroville.

More than 50 years later, the identity of what it means to be an Aurovillian continues to develop. Most people who have decided to become a part of this community, or are born into it, willingly offer their expertise and services in the hope of the brighter future that The Mother and Sri Aurobindo foresaw, embracing new technology for innovations in sustainable living. In this respect, some Aurovillians remain committed to continuing building the township as per Anger’s Galaxy Plan for a projected population of 50,000 people. Recently, however, Auroville has reached a crossroads, with some residents starting to challenge whether the faithful completion of the masterplan should be prioritised above all else. At the centre of this debate is the construction of Crown Road, a second circular road around Matrimandir that would link the four main zones in the masterplan. For the past two years, discussions over its implementation have prompted a prolonged period of indecision about a defining element in the township’s future development.

With mounting tension within the community, and pressure from the central government of India (which partially funds Auroville’s development along with NGOs and private donors) to go forward with the approved masterplan, Auroville stands on the brink of change. Some residents hold the view that The Mother’s vision of spiritual consciousness for all cannot be realised without building the township, exactly as she had instructed. Others, who are sometimes labelled as ‘anti-Galaxy’, are of the opinion that Anger’s masterplan is only a broader scheme for Auroville’s incremental growth and need not be followed to the last letter. They believe that it should be adapted to the present ground realities and actual usage.

“Auroville will be the place of an unending education, of constant progress and a youth that never ages”

My first trip to Aurvoille in March 2021 was the result of an open design call to create four out of the 12 main gardens in the Peace Area. Announced by the Matrimandir executives in 2019, the open call aimed to shortlist conceptual entries after a two-stage process. Along with my colleague Vir Shah and two other selected teams, I was invited for a 15-day stay in Auroville as part of the process. Personally, the thrill of our designs going forward was quickly surpassed by the chance to tour the township accompanied by Aurovillians, which covered everything from public buildings and schools, to forest walks and waste management systems.

Our visit was largely aimed at addressing one of the major drawbacks of the anonymous design selection process for the project (the first design call opened to people outside of the community), which resulted in inviting designers with a limited understanding of the place, its ecology and social structure. The selected teams had also been brought together to Auroville in the hope that our designs could be integrated over a period of two weeks, and that the outcome would be superior to what the individual teams had proposed. Ultimately, since one team did not show up, Vir and I joined hands with the third selected designer, Anandit Sachdev, to present a collective proposal to the community for all four gardens.

“We worked with the agenda of restoring peace in the Peace Area while formulating the selection process,” says Hemant Shekhar, a Matrimandir executive at the time, and our primary host during the first visit. “The gardens had not progressed for six years due to the internal conflicts in Auroville.” The Matrimandir gardens are part of Anger’s Galaxy Plan and were each assigned a spiritual theme by The Mother, along with a list of flowers that she had chosen for them. They are the embodiment of the spiritual teachings of Sri Aurobindo and The Mother, and together with Matrimandir symbolise the spirit of unity that gave birth to Auroville. In essence, the 12 gardens aspire to reveal specific spiritual qualities to those walking through them before entering Matrimandir for silent meditation. However, the detailed designs for the gardens by Anger, and subsequent proposals given by other creatives, had not been implemented due to disagreements in the community over the designs not physically translating The Mother’s concepts to a satisfactory level.

With mounting tension within the community, and pressure from the central government… Auroville stands on the brink of change

After reaching a dead end, the executive committee was reshuffled in 2018 to start the process afresh. “The only way ahead was to come up with a fair procedure to invite new ideas for the four gardens of Light, Life, Power and Wealth,” says Shekhar. The selection process included two rounds of community feedback, as well as suggestions from a neutral international panel of landscape architects. While the manifestation of all 12 gardens will certainly help inch closer to The Mother’s original vision for Auroville, there is mounting frustration in the community at the slow pace of reaching consensus, as well as the lack of unified support that is required from within the township to make bigger things happen.

“Fifty-three years have passed by without much progress in the physical manifestation of the township,” the TDC (Town Development Council), a planning body made up of Aurovillians, stated in the October 2021 issue of Auroville Today. “The Crown being a fundamental component of the Galaxy, without manifesting it, the township cannot be manifested. This is imperative to protect Auroville from outside suburban sprawl and tackle the threats to our natural resources.”

Auroville’s proximity to Chennai and Puducherry, as well as its growing popularity amongst tourists, has resulted in numerous commercial investments and unregistered settlements in the area in and around Auroville – land that has already been designated to the township for the development of its masterplan. These developments have particularly cropped up in the 1.25 km-wide Green Belt of forest cover around the township as per the Galaxy Plan. In addition to this, there are also farmlands and houses owned by Tamil locals, legally registered with the state government, that lie within the 2000 ha. of Aurovillian land allocated to the township by the central government of India. It is estimated that the Auroville Foundation has only managed to acquire 850 ha. of that land so far.

Various committees have been formed in Auroville to study the situation and negotiate with local villagers who have ancestral connections with the same land and whose families have been living here even before Auroville was established. Technically, all the land required to develop the 5-km diametre township is already collectively owned by Auroville and none of it needs to be acquired. However, the community has refrained from taking the extreme measure of forced eviction.

Right: Auroville invites people from all countries to join their spiritual community. Twelve main gardens surround Matrimandir — the meditation pavilion

“The big mistake we made in 1999 was to go to the central government to get approval for our masterplan, when land matters are a state subject in India,” notes Paul Vincent, in an interview given to Auroville Today in August 2019. “Even if the state government constitutes a new Town Development Authority (for Auroville) and accepts our masterplan, a Detailed Development Plan still needs to be created, which defines what will happen on each plot of land.”

Today, Aurovillians still have to defend their claim on the land assigned to them by the central government, because locals have competing approvals issued by the Tamil Nadu Government. Vincent, who has been involved with trying to protect Auroville’s physical integrity since 1975, explains that the land threats began around 1994 after many permanent structures had already been erected, prompting villagers to realise that land could be sold off at higher prices to the Aurovillians, who seemed to be serious about building a township. Where negotiations have not worked, land litigation cases are being heard in court.

To add to the complexity of the situation, some Aurovillians themselves have purchased land in the Green Belt to develop commercial property or private residences. Some of them claim that these private deals are one way of securing land for Auroville, although they have continued to keep the property under their own names instead of donating it to the Foundation. Some of these same people also oppose the development of the Crown Road, which would eventually be followed by the implementation of the rest of the Galaxy Plan and the loss of their private land. Many Auroville residents who have knowingly erected their houses in the way of the Crown Road have been accused of usurping land meant for the growth of the township.

Architects and planners in Auroville have taken an ecology-sensitive stand on the matter. They believe that the masterplan should be tweaked and adjusted to accommodate fully grown trees, water catchment areas and paths that have organically developed over time. One of them is Prashant Hedao, a landscape architect and urban planner who has been active in the bio-regional planning of Auroville. “For a circular township like ours, a road connecting the four zones is needed,” he says. “I don’t think many people have a problem with the Crown; it is how and when it is to be implemented that needs to be discussed.” It is a debate that Hedao knows well, having been a member of the TDC from 2007 to 2009. “This is not a township we should build in a hurry,” he told the local press in Auroville in 2021. “Where we should be putting our energies is in supporting activities and building institutions, which would attract the right kind of people.”

Right: The physical core of Auroville, with Matrimandir at its centre, is called the Peace Area

Hedao, however, feels these inputs are not being incorporated in Auroville’s current planning approach because the TDC is fixated on the symbolism of the Galaxy Plan and its specific geometry, such as the Crown Road, which is designed to be a perfect circle and 16.7 metres wide. Since Auroville is envisioned to primarily be a cycling and pedestrian township, it is argued that the proposed road width will not add to its functionality, but will instead only invite more vehicles and thereby increase traffic rather than reduce it. Hedao asserts that all the sections of the proposed road need to be studied and treated differently, based on context and need. Some part of the Crown Road goes through the Darkali forest area, with close proximity to a village settlement that is infamous for anti-social activities such as alcohol abuse, as well as incidents of sexual assault. Adding a road through Darkali, which would likely be used by a limited number of Aurovillians, may pose a safety threat. Since the Galaxy Plan was developed for a total capacity of 50,000 people, Hedao argues, it should be executed in a phased manner as resident numbers grow.

To some extent, the community is now coming together to discuss some of these pressing issues concerning the township and are striving to resolve them amicably. To bridge the increasing gap in opinions and review things more critically, Aurovillian architects, planning experts and other residents are conducting studies on the Crown Road proposal and documenting the actualities on site. They have also engaged Vastu Shilpa Consultants, the architecture firm led by Pritzker Prize winner B.V. Doshi, to prepare a Detailed Project Report for the same stretch. The ‘dream-weaving’ sessions, which have been happening since late January 2022, are a collaborative effort to bring different ideas together on one table and to decide on a common direction to follow. The participants are now listing some short-term goals to be worked upon, and presenting an alternate proposal for the Crown Road to the Foundation.

“Here’s a township which can present an alternative model to the world since our mega cities are not proving to be the most sustainable”

“It is important to understand Auroville in totality, with its environmental setting and social impact on the surrounding villages,” says Hedao. “Here’s a township which can present an alternative model to the world since our mega cities are not proving to be the most sustainable.” Auroville has tested many eco-friendly methods of constructing buildings, roads and dams, and is working with the agenda of using solar energy as its prime source of generating electricity. The township is also revitalising natural sources of water and biodiversity, preserving indigenous seeds, and documenting local wisdom around the use of different trees and shrubs, as well as running outreach programmes for health and education in the surrounding villages.

While the Crown Road controversy may have exposed the limitations and challenges of a community-driven governance, it is also proving to be a tool to fine-tune Auroville’s methods and clear the path for inevitable change. Aurovillians are now engaged in an internal dialogue to decide on the best way ahead. With added pressure from both the state and central governments, and other external factors of increasing tourist flow and land encroachments, the road to utopia is not smooth. Some residents are even considering going back to their home countries until harmony is restored and Auroville’s future is secured. While people are feeling forces close in from all directions, with predictions of a government takeover or the township becoming engulfed in suburban sprawl, many prefer to remain optimistic. There is an increasing awareness in the community of the need to “take our time to work together and not hurt each other in the process of reaching our goal”, observes Elvira from Germany, who works as a change management consultant in Auroville. “I’m trying to listen to the different bubbles in this participatory movement, and to initiate that we talk to each other so we can create synergy,” she says. “But we are a bunch of individualists, and there are too many leaders,” she laughs. “However, by letting myself get involved in this, I see new connections emerging around me. It’s magical; there is a feeling of belonging here.”

(This is a shorter version of the article “The Road to Utopia is not Smooth” published in Disegno Journal (Issue 34), August 2022.)

All Photos: Alessandra Silver

Comments (0)