The urbanisation of agricultural land located on the peripheral/peri-urban boundaries of cities has been identified as one of the key State strategies to undertake planned development in metropolitan areas. There has been a considerable change over time in the land development and planning model – shifting from State-led land acquisition and comprehensive planning towards adopting a more market-led private sector planning approach. As a result, the speculation around real estate and farm lands, has tremendously influenced the new relations around land.

Master Programme: Urban Policy and Governance

Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, India

Most stakeholders associated with land are encouraged to speculate based on various factors as well as their social, economic, spatial and political positions in society. Gururani and Rajarshi (2018) argue that it is the changing agrarian dynamics that set South Asian urbanisation apart from the dominant modes of suburbanisms and suburbanisation in the Global North. This article briefly discusses the shifting role of the State in the development of peri-urban areas by examining the land pooling policy introduced by the Delhi Development Authority (DDA). Focusing on one peri-urban village in Delhi, this write-up examines the manifestation of the policy on ground and assesses how local agrarian relations and equations have a large bearing on the development pattern that emerges in response to State-led land development.

Land development approach in Delhi

The DDA, in its Master Plan of Delhi (MPD) 1962, followed a regionalist model and acquired about 35,000 acres of land all around Delhi through a large-scale land acquisition policy under the Land Acquisition Act of 1857 to ‘reduce land speculation and provide enough housing facilities for the Government and for other purposes.’ As Bhan (2013) writes, though DDA kept acquiring the land, it was not followed by corresponding large-scale housing development. The poor and Economically Weaker Sections (EWS) continued to struggle to access affordable housing and the pressure was on peripheral areas where most of the unauthorised colonies had sprung up. And the infrastructural services failed to develop at the same rate.

Owing to the dissatisfaction of the landowners with the amount of compensation offered by DDA leading to disputes and litigations, delay in allotment and increase in the cost of land and challenges in the implementation of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (LARR) Act, 2013, DDA pushed to look for an alternative model that could provide a more feasible mode of land development. The land pooling model introduced in 2013, provided one such strategy to develop areas on Delhi’s periphery. However, due to a change in the political regime at the Central and State levels, and objections to various provisions of the policy, DDA took five years to revise and notify the new land pooling policy, which came into effect in 2018.

Due to a change in the political regime at the Central and State levels… DDA took five years to revise and notify the new land pooling policy, which came into effect in 2018

The revised policy exclusively mentions ‘private sector’ as an active player in the development of Delhi, starkly different from earlier land acquisition policies of the government. The policy portrays the outcome to be ‘world class, smart and sustainable neighbourhoods’, using words such as ‘world class’, ‘smart’, and ‘increase in value of land’. What is different in this new approach is the function of these private developers and large landowners in the planning, design and regulation of urban spaces on a much larger scale, which was previously confined to the scale of a building or at the most a block. As also discussed by Roy and Ong (2011), this marks a larger shift in the role of states from imposing modernist visions, to a more entrepreneurial role in facilitating private-sector development as a means of capitalising on the economic opportunities presented by globalisation.

The question of emerging spaces within the peri-urban areas

The villages located in peri-urban areas provide a unique intersection of social, spatial, economic and environmental mechanisms of a place. With the focus shifting to centrality of land, the urbanisation in South Asian cities revolves around these spaces of peri-urban areas. These peri-urban areas are characterised by messy and highly contested processes of conversion, acquisition and privatisation of agricultural land. In the context of Gurgaon, Shubhra Gururani discusses how in agrarian societies like India, only by understanding how rural and urban are coproduced, can we begin to understand the complex process of suburbanisation and recognise that the urban question is indeed also the ‘agrarian question’. Thus, the shift in the State’s planning approach to encourage speculation by a host of private actors becomes important to analyse in the context of peri-urban areas as they are the next set of spaces that would be subsumed within the course of urbanisation.

Establishing correlation between land ownership and pooled land

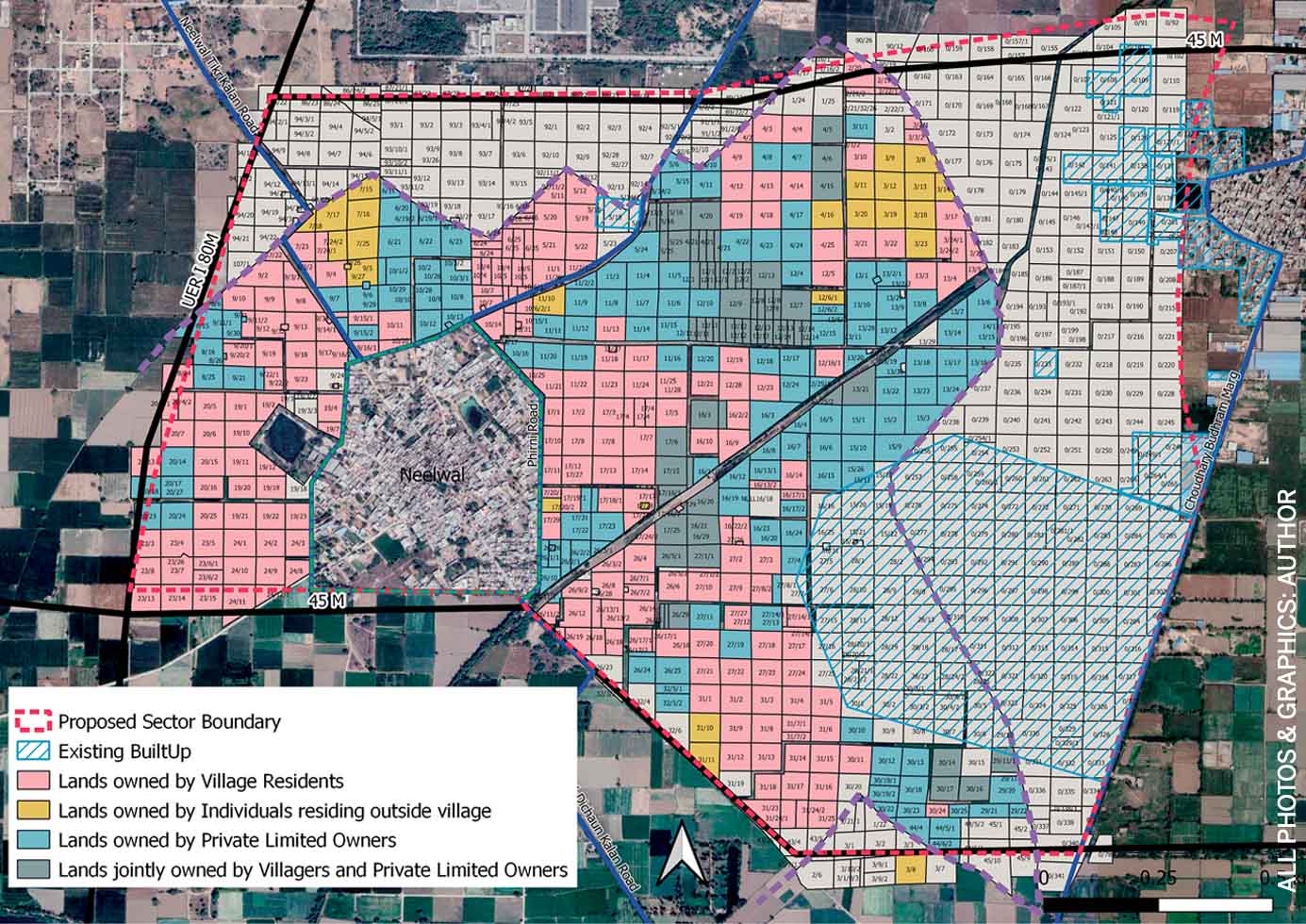

The qualitative case study approach that relied on mapping analysis was used to focus on one village i.e., Neelwal Village located in Zone L and proposed Sector 03 of the land pooling policy. As per Census 2011, the area of the village is 340.60 Ha. and has a population of 2637. The houses constructed inside the village reveal a mixture of both urban and rural characteristics with people still engaged in cattle or agriculturally based livelihood activities.

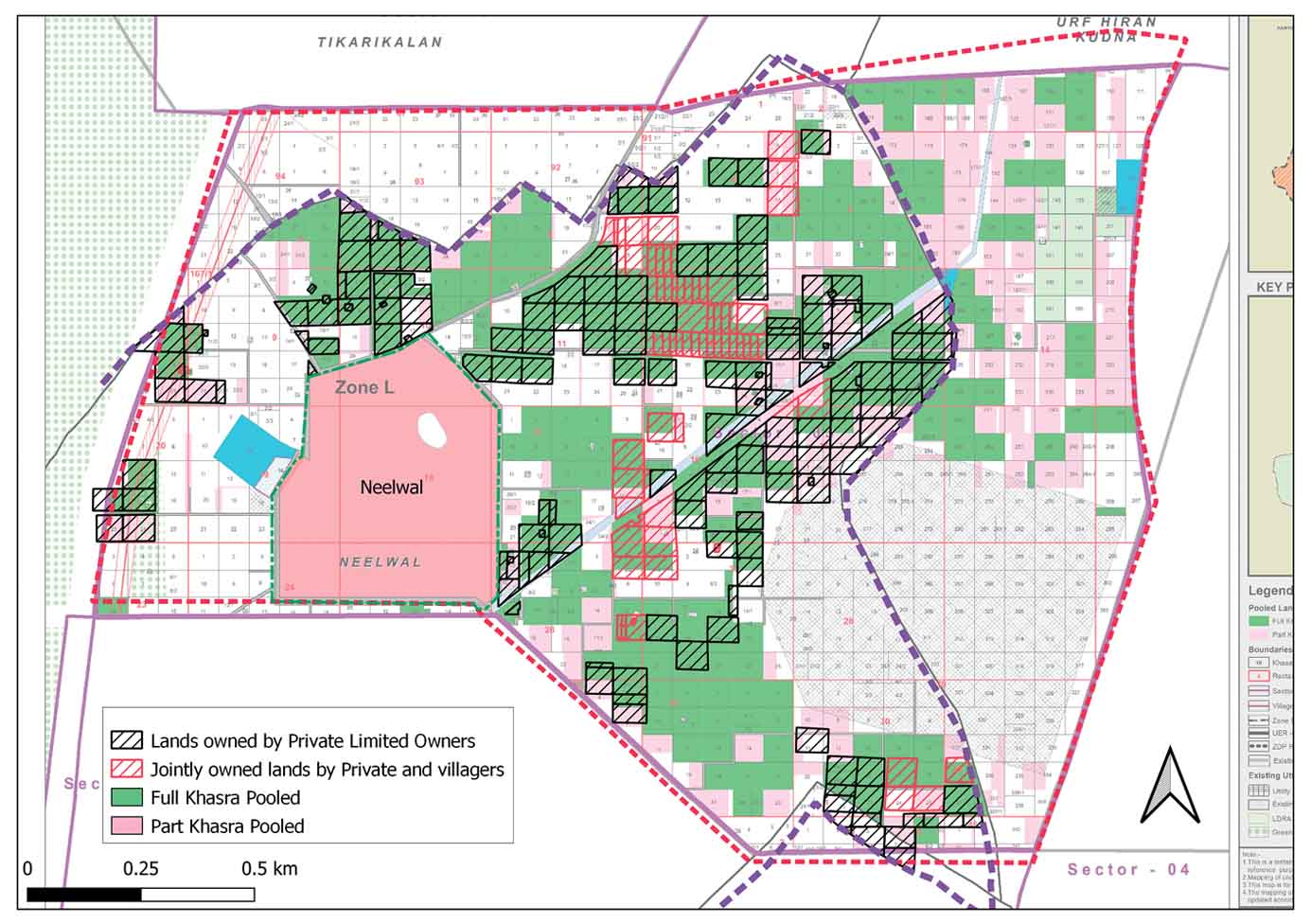

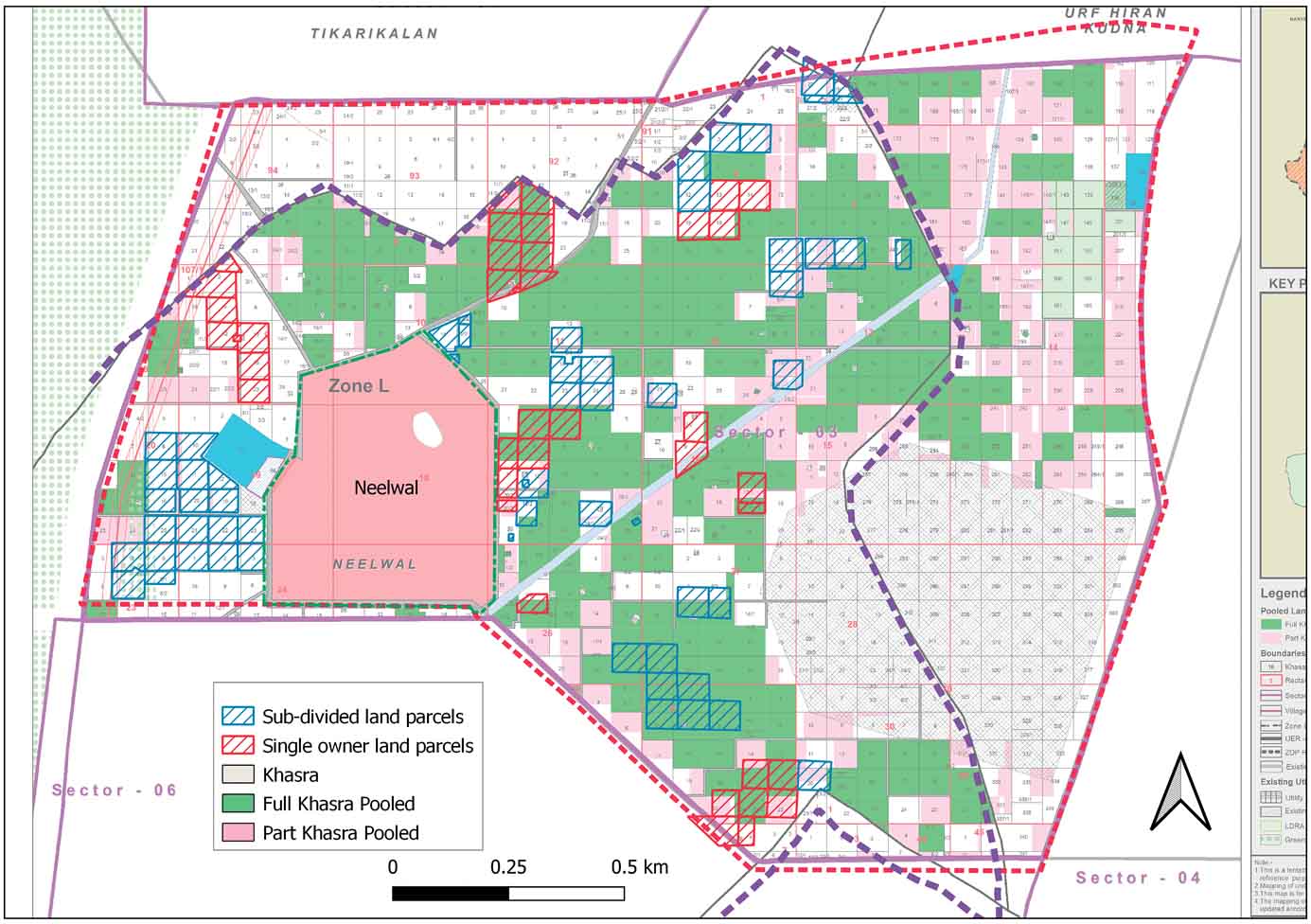

Spatial mapping exercise using Geographic Information System (GIS), coupled with land ownership data revealed interesting insights into the land pooling process. Four types of land ownership details could be found i.e., land parcels owned by residents of the village, land parcels owned by individuals not residing in the village, land parcels owned by registered private limited companies/builders/developers and land parcels jointly owned by village residents and private developers.

Private players versus village landowners

The lands owned by private players are continuous land parcels consolidated on a large area that would provide an advantage when the consortium is formed and redistribution of land takes place. It is observed that those who own most of the land belonging to private builders and developers independently or jointly with villagers, have shown willingness to register their land under the land pooling policy. Further, a significant amount of these lands is owned by a single real estate developer group, purchased over a period of time when the policy was first announced in 2013. Thus, private builders and developers are major stakeholders who drive the land pooling process in the village.

Lands owned by private limited owners and pooled land

The lands owned by villagers are divided into two types: small and marginal lands i.e., land parcels subdivided and owned by multiple owners and large lands i.e., land parcels owned by a single owner. With the subdivision of land into small land parcels of less than 2 hectares, these land owners cannot individually be part of the consortium and are thus excluded from the formal process of sector planning. The land owned by villagers whether fragmented or consolidated lies mostly in different parts of the proposed sector unlike the land owned by private developers, which is mostly continuous. This might put villagers at a significant disadvantage at the time of redistribution of land because the policy is silent on the redistribution process.

Lands owned by villagers and pooled land

With the participation of private players in the land pooling policy, the village landowners constantly referred to the competition between them and developers and how the latter will be benefitted in the long run. Village landowners said: “A landowner who owns land between one and two acres will either have to collude with a developer or form a group with other small landowners to be part of the consortium. Developers will first develop their land rather than ours.” The policy does not allow landowners who own less than 2 hectares of land to be part of the consortium, therefore making the process unfair for smaller landowners because they have no say in the land distribution process.

The policy does not allow landowners who own less than 2 hectares of land to be part of the consortium, therefore making the process unfair

Highlighting the monetary comparison between a farmer and a private developer, one village elder said, “We will not be able to sell flats, but the developer will be able to do so because they have good contacts. We neither have contacts nor the money and we might have to consult a builder to sell our flat and he will charge a huge amount of money.” Bose (1980), has studied that the advantage from the appreciation and selling of land benefitted only a few. A.K. Mehra highlighted in his study that barring a few people who could strike a better deal because of their social, economic and political situation, the people of urbanised villages fell prey to speculative private builders and developers who cheated them.

Uncertainty about policy provisions

The ambiguity over the implementation of the land pooling policy remains a cause of concern for landowners to register their land under the policy. The issue was highlighted by villagers in Neelwal who said, “There is an apprehension among the villagers that, if the land is directly registered under DDA, we don’t know when the development will take place and it could be the same for many years. How will we feed our children, what will we eat?” Since the policy has already been delayed by DDA for about nine years, and amendments are still being made, landowners believe that the policy will take years to be implemented for them to get their pooled lands back.

Conclusion

The land pooling policy has emerged as one of the prominent land reorganisation and development tools in India. With the State acting only as a facilitator, the economic, social and spatial situations around land reveal that everything cannot be left for the consortium to decide. While speculation around land continues, and is further expected to increase, with each stakeholder expecting to benefit and make a profit in the long run, the study raises a question on inclusive, affordable and accessible housing for the poor income groups including the small land owners inside the village. Half of the EWS housing is left for the consortium to build; it would be critical to evaluate the affordability and even the availability of such a category of housing. The State has to play a pro-active role in ensuring transparency, availability, accessibility and delivering of information to all the stakeholders to achieve an equitable form of development.

Mentor: Dr. Lalitha Kamath

Comments (0)