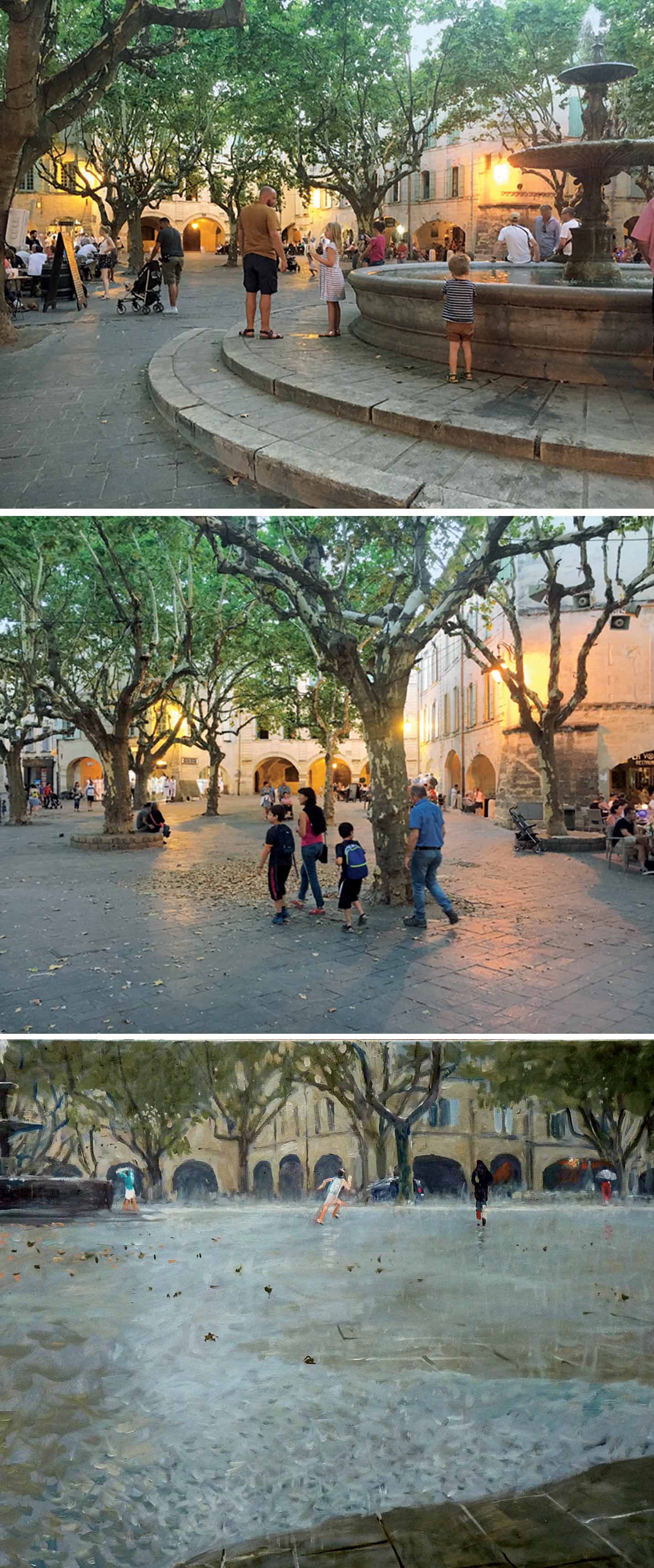

In July 2017 I spent an entire week exploring Uzès, a delightful French town with Roman origins and a beautiful medieval structure. Built around the Duché d’Uzès, the town has small-scale, random, narrow medieval streets interspersed with interesting public spaces. The largest and most central is the main market place called the Place aux Herbes, where a canopy of plane trees provide welcome shade in the hot southern French summers.

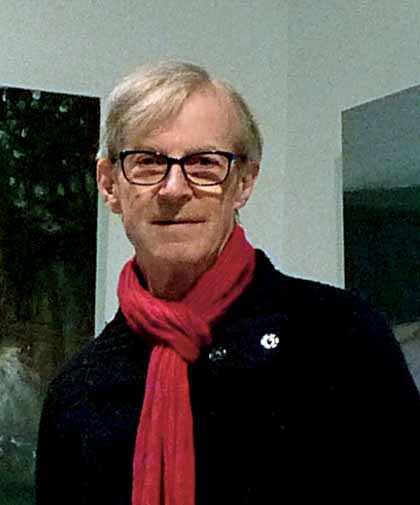

Oliver Bevan has been investigating Uzès for years, as a phase in his almost half a century of ‘exploring the city’, which has taken him from London to Saskatoon, Canada, and then via London to Uzès, France. He has visited, but more importantly, painted cities like Venice, Paris and Barcelona and also smaller cities like Montpellier, Siena, Florence Casole d’Elsa (a village in Tuscany) as well as many, many others, giving each creation his own interpretation.

During his five decades of urban explorations through the medium of painting, Oliver Bevan’s works have evolved from abstract geometric images, via more spontaneous forms of abstraction, on to a more impressionistic urban realism.

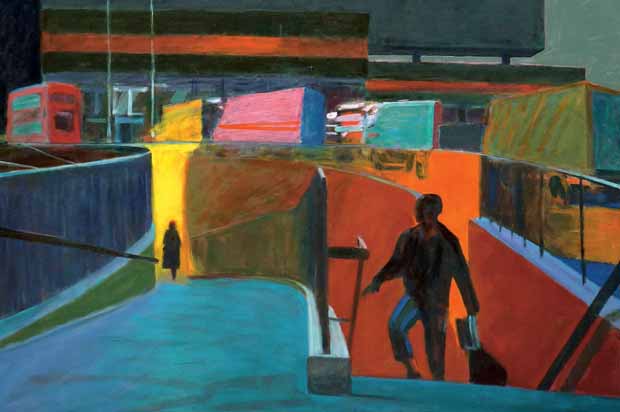

What is constant, however, in all of his work is his understanding of city life as it takes place in urban spaces. For Oliver Bevan understands the city and its public spaces. And like few artists, his paintings interpret these on vastly different scales: From the scale of silhouette and urban structure via squares and streets, to details of public spaces, including unusually cropped sections of a fountain, a colonnade or a tree. Some of his work is totally devoid of any human figures, so the object of study is the ephemeral spatial quality of that city, while some depict human figures as they interact with these urban public spaces.

The painter is partly a witness to the city he paints, but he is also a dreamer

Oliver Bevan’s approach to painting cityscapes can best be described by quoting a few sentences from his introduction to an exhibition he participated in and created in 1993 in the UK called ‘Witnesses and Dreamers’: “The city is a particularly apt analogy for the human mind, because it too is a system of pathways and connections in which certain areas have specialised functions; attractive facades may hide sordid and secretive interiors. In making the city the subject of our paintings, we are making images uniquely expressive of ourselves.” He went on to explain “… for some artists, these autobiographical aspects are dominant, while for others a passionate objectivity is crucial.”

According to Oliver, the painter is partly a witness to the city he paints, but he is also a dreamer giving form to his own thoughts and emotions in his paintings.

It is in this unique combination of these two roles that a painter produces each painting.

I met Oliver Bevan at his studio to discuss his love of cities and their spaces.

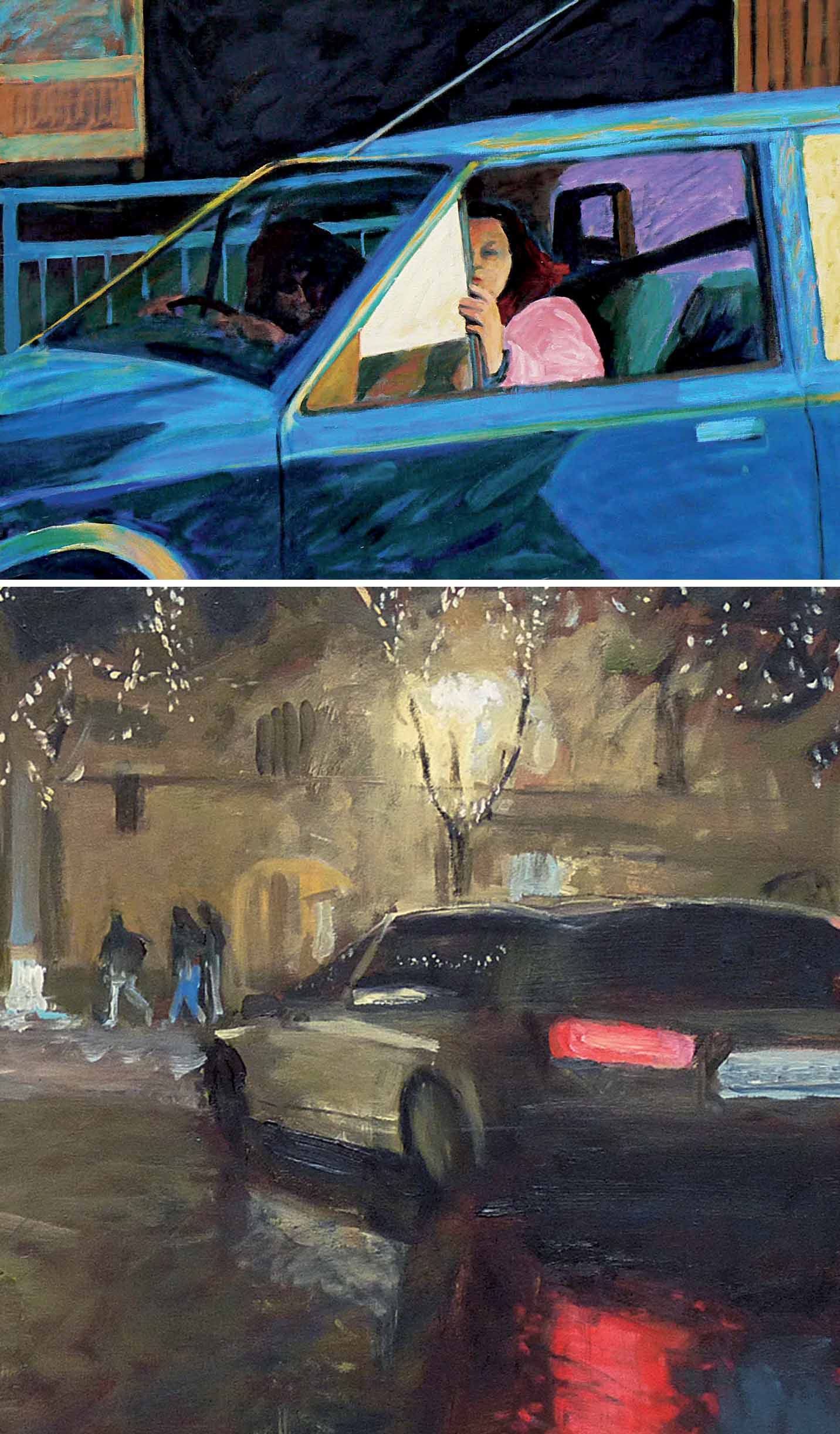

Bottom: Car Night

As an urban designer I look at urban spaces and how they work 24x7. In your paintings you capture the ephemeral city. Which moments do you really choose to portray? What triggers your emotion?

As I wander through a new city, sometimes, to my complete surprise, I come across spaces that give me a sense of exultation. It is these moments, which I try to capture in my work. For instance in Venice, when coming out of a narrow street, I suddenly found myself in front of the wide expanse of the Piazza San Marco. This is how the city reveals itself dramatically and demands to be painted! The Paris canvas happened purely by accident. On my way back into the city the train stopped at La Défense and I decided to get off and explore. Once I had taken the lift to the top of the magnificent ‘Arche’ there was a certain mistiness in the air, nothing beautiful about it, probably just smog, but the view along that axis towards the Arc de Triomphe with the Eiffel Tower just visible above the lower buildings to the right, was completely mind-blowing. Again, I had this strong urge to record that moment.

The idea of painting the rain in Uzès came after a particularly hot spell; a thunderstorm exploded over de Place aux Herbes. The suddenness and ferocity of the rain sent everybody scurrying for shelter. The unexpected storm had animated an urban space in a way I had not seen before. These are the sort of moments I need to depict.

The unexpected storm had animated an urban space in a way I had not seen before

What is so special about water that it inspires you in so many ways?

I’ll answer that in a roundabout way if you will allow me. Everyone must have seen photographs of figures walking past advertisement hoardings. If we were on the spot we would have no difficulty disentangling the reality of the figures from the flat expanse of the advertisement, but in the photo the two levels of illusion become equal and almost unified, creating a delightful confusion. Water acts in the same sort of way. In the painting, the illusions caused by reflections are integrated into the image and given equal value. Our brains, or at least mine, seem to be delighted by this ambiguity, which fuses two levels of reality. Even the sheen on a humid floor surface works the same magic. Cropping the image in a certain way can considerably enhance this effect. There is nothing quite like water to play with and modify the fall of light, whether in the form of puddles, fountains, rivers or the sea. From time to time an expanse of glass like the Pyramid in Paris almost rivals water in this respect.

Top Right: Towards Me

Bottom: Flooded Terrace, oil on canvas

Bottom: Artist’s interpretation of its ephemeral moments

My next question is about how people and human activity occupies public spaces. While some of your paintings are devoid of people, there are others where the human participation is the focus of your interest. The public space is almost a backdrop for human activity. What sort of human activities trigger you to paint?

With certain exceptions I tend to paint people enjoying the public spaces they occupy and use. It is a kind of happiness mirroring my own that inspires me. Even people in a traffic jam, sitting in their cars, don’t seem to be particularly miserable. They willingly take part in a kind of colourful pageant.

But in certain paintings the human actors seem oppressed or resistant to the architectural context in which they find themselves. The large canvas ‘Looking Back’ for instance shows two people, one is static and the other in movement on ramps leading to a pedestrian subway. I used strong contrast and intense colour to amplify the dramatic atmosphere around these two characters that remind me of Orpheus and Euridice (Orpheus has the right to lead Euridice back from the Underworld, but he must not turn round to look at or speak to her or she will die.)

The illusions caused by reflections are integrated into the image and given equal value

In your interview with Will Self, you contend that just as the rail termini are now considered monuments, so too in due time the motorway infrastructure will be promoted to heritage status. So this question is about cars in public spaces. As designers we often want to wish the cars away, while what we should be doing is always looking for a right balance between pedestrians and cars. In your paintings, not only do you include cars, you also exploit them in your urban cityscape compositions.

This is an interesting topic. Unlike most painters I accept them. Up until the 19th century, the horse and horse-drawn vehicles were major subjects for painters. When the cars arrived in large numbers in the city, the photographers and filmmakers delighted in including them in their creative work, but somehow most of the painters decided that it was not for them. They are willing to put pretty boats in their compositions, but no cars!

I guess I have accepted cars as being part of our public spaces. Some time back, I did a few paintings of London buses and curiously the paintings with the iconic London buses were very popular while the paintings with just cars failed to sell. There are plenty of cars in Pop Art, but that jokey advert-like quality is very much what I want to avoid.

All photographs: Oliver Bevan

Comments (0)