I spent a few years of my childhood in Zampa Bazaar in Surat, India, after my parents migrated from Kolkata. We lived adjacent to the Masjid Al-Moazzam, which is part of the Dawoodi Bohra congregation. Like many neighbourhoods in the immediate area, a private backyard was nonexistent. Children were forced to interact with the public spaces in front of their residences, often sharing them with an inflow of people. These spaces also coincided with access roads teeming with rickshaws and bicycles and crates of export goods transported by livestock. Together, everyone shared a common public space. Another dimension to this shared space was the proximity between residential, retail and religious uses.

As I grew up, my father often evoked memories of my early childhood when I would jump back-and-forth within the Masjid’s courtyard and the adjacent Machhiwad Khari Road. The side yard space of our residence spilled into the courtyard of the Masjid Al-Moazzam where rows of ‘mom-and-pop’ shops lined the entrance to the Masjid. While these buildings had different uses, during special festivities such as weddings, processions or the call to prayer, the secular and nonsecular spaces became a unified public space. The throng of Dawoodi Bohras merged the public roads into sacred grounds to conduct prayer in every available space (Figure 1). Like Surat, many other cities in India exemplify the utilisation of public space with a religious interface. But on a broader scale, this phenomenon is not that different from those in many other cities across the world.

Cultural and religious groups have given a timeless quality to spaces

One of the most intriguing facets of public spaces is the way they are defined among cross- cultural influences and their reconstruction from secular definitions. For instance, Buddhists meditate at shrines that are tucked away in the alleys of Japan’s metropolitan areas, Muslims can be seen prostrating in prayer on America’s suburban sidewalks and Catholics can be heard hymning at church courtyards in South America’s city centres. These manifestations of religion and their conceptions of space embedded through the built environment reflect theological and cultural understandings that shape the public sphere and give meaning to social cohesion.

After leaving Surat, I have been living in California for more than 20 years now and as a member of the Dawoodi Bohra community, I have often observed the differences between sacred versus non-sacred spaces in the ‘western’ city. Let’s examines the values held by the Dawoodi Bohra community and the purpose of their physical structures and the way they perceive, use and attempt to regulate public spaces in an ever- changing landscape between the mundane and the spiritual worlds.

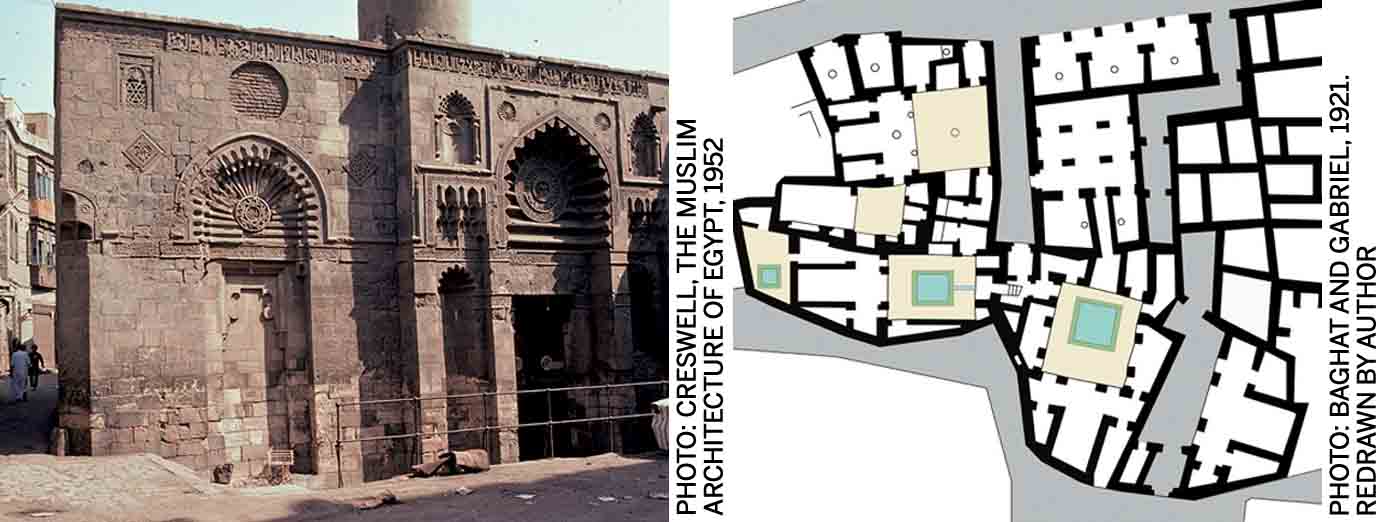

Figure 3: Fatimid courtyard gardens and pools in the city of Fustat, Egypt

Perceptions of the Public Realm

Religious spaces may be built on the premise of divine understandings, traditions and rituals, language, archetypes, phenomenology or emotions and memory. The Dawoodi Bohra community has held long-established meanings to their public spaces. Their vestiges can be traced from the Fãtïmid Dynasty during the reign of the 11th Imam, Abdullah al-Mahdi, who founded the City of al-Mahdiyya on January 6, 910 A.D. along the northeastern coast of Tunisia (Haji 2012).

The first Fãtïmid city was built in Cairo on July 6, 969 A.D. by the 14th Imam, Maad al-Moiz li-Dinillah (Zahran 1989). Cairo was built as a new Fãtïmid city from the old City of Fustãt. The areas between Cairo and Fustãt became a ‘green belt’, where abandoned areas were converted into parks and gardens (Raymond, 2000). Inside the city walls of Fãtïmid, Cairo, gardens with water features and open spaces, the establishment of new palaces, mosques and residences were symbolic of a new world order as they were the first Shi’ite Dynasty to have political and territorial gains after the 1st Imam, Ali Ibn Abu Talib (AS). Their spaces were an exertion of dominance for rulers to create new and meaningful places (Figure 2). Scholars have said that gardens in medieval Cairo served as spaces for meditation and theological studies and were valued for their aesthetic appeal and they also served as ceremonial courts for the Imam to participate in cultural festivities (Figure 3). By 971 A.D., Cairo’s cityscape served as a microcosm that nurtured a diverse community with many ethnic groups which, at the same time, interacted as a single community (Bloom 1980).

Like many Muslim schools of thought, an Imam is a central and prominent figure in their faith. Similarly, the Dawoodi Bohra community believes in an appointed leader, the al-Dai al- Mutlaq (Summoner of Faith) after the seclusion of their 21st Imam in 1132 A.D. As an extension of the prominent aspects of Fãtïmid urban planning, His Holiness, Dr. Syedna Mohammed Burhanuddin (RA) has prescribed four institutions for community design: The Masjid (mosque) caters to religious activities, the Manzil or residence, upholds traditional and cultural beliefs, the Madrasa is the centre for cultivating Islamic pedagogy and the Mujtama, or the public realm, connects all the three elements within the Dawoodi Bohra community.

Today, the Bohras have become a global urban phenomenon whose prominent migration patterns have clustered in the town where their al-Dai al-Mutlaq lives or often migrate to places near the vicinity of a masjid. Their urbanism continues to develop with major geographic concentrations in Southeast Asia: Mumbai, Surat, Ahmedabad, Dahod, Ujjain, Nagpur, Pune and Kolkata in India and Karachi in Pakistan. Other parts of the world include the Middle East, East Asia and various parts of the western world, which have grown to an approximate 1.2 million Shi’ite Muslims (Fleet et al., 2013).

The public domain in the Bohra community can be understood on two scales. On a global scale, the community has developed a system of Anjumans or ‘sanctioned committees,’ which operate as complete administrative, judicial and religious systems in all public a airs of the community. Its purpose serves as a network of community-building from global to national and the community level, thereby uniting every Dawoodi Bohra worldwide. On the community scale, their public spaces articulate an ethos of spiritual habitation (Figure 4). In the heart of the complex is the great masjid surrounded by its courtyard and garden spaces that define ancient living traditions and ceremonies with prescribed rituals. Their architectural identity plus their salutations and acts of homage convey a clearly-defined lifestyle that changes the space within and around them (Sanders, 1994). These extraordinary spaces serve as ‘doorways to another world, reminding us that life is more mysterious and wonderful than we can ever imagine. They evoke awe and reverence in us’ (Carr-Gomm, 2008). Although these spaces are concocted by religious significance, they also evoke ‘a sense of wonder’ and imagination.

Meanings of Public Spaces in the American City

In the book, The City: A Global History, author Joel Kotkin chronicles the idea of urban areas to serve three functions: the development of sacred space, space as a means of security and spaces that function as commercial markets. Sacred spaces are places where unique activities occur and invite individuals to explore their own meanings. Secular nations are often challenged to achieve social cohesion in the face of surmounting religious and spiritual diversity.

American cities have become the recipients of multi-ethnic enclaves due to shifts of global migration. They have been shaped in myriad ways with their architecture, idioms and cultural identity. Evidently, much of modernity illustrates people damaging their environments, from small spaces to entire continents (Gandelsonas et al, 2002). “Americans experience modernity as a birthright; America does not strive for modernity, it defines modernity.” (Feenberg, 1995). It is important to distinguish how American cityscapes define their public spaces. From colonial America to contemporary American cities, we witness American public spaces as a mass of city or town centres with commercial hubs, parks and open spaces and civic engagements that are merely driven by economic and political forces. Numerous studies have also been undertaken by urban theorists, including Walt Whitman who was preoccupied by the idea of public spaces for collective and individual participation. Jane Jacobs has also described public spaces with a ‘sense of loss’ and recovering the idea of a ‘sense of place’.

As these spaces continue to develop, they cultivate connections with the rest of the community

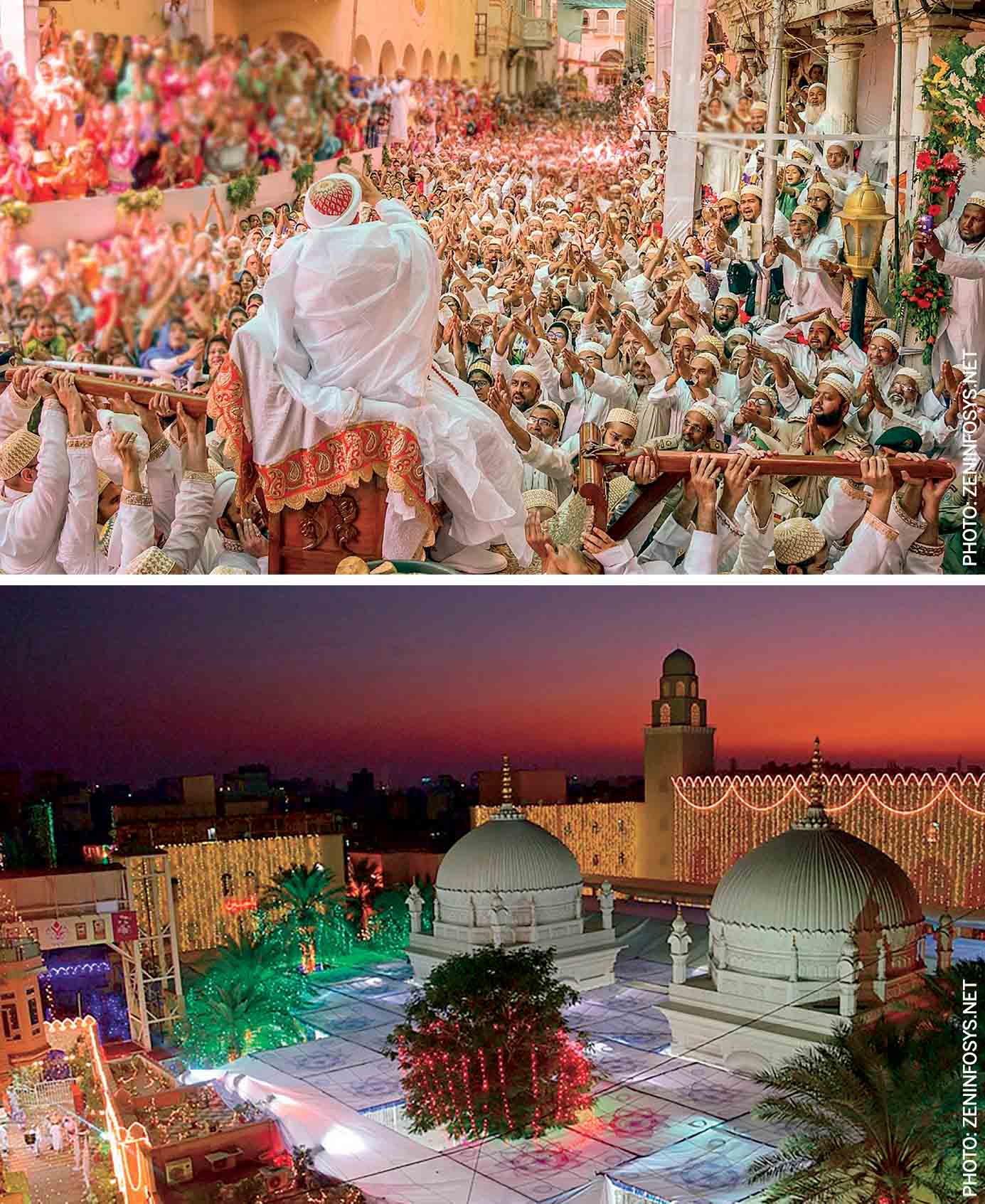

Evidently, cultural and religious groups have given a timeless quality to spaces with a phenomenon that articulates a way of life that transcends the past, present and the future dialogue of urban formation. For the Dawoodi Bohras, they redesign spaces to accommodate daily and annual rituals and, when there are limitations to their spaces, they effectively recreate the spaces around them. For instance, they manage to pray in any place during the time of prayer, including sidewalks, streets or communal areas. Other example are the processions on streets and roads during special occasions or weddings where Dawoodi Bohras congregate and chant as they walk toward the masjid for the primary ceremony (Figure 5).

The Ashara occasion is an annual pilgrimage where thousands of Dawoodi Bohras travel to different parts of the world with the al-Dai al-Mutlaq who delivers sermons for nine days during the first month of the Islamic calendar, Moharram al-Haraam. The event commemorates Ashura or the 10th day of mourning for the Prophet’s grandson and 3rd Imam, Hussain, (AS) who was martyred. To make this a successful event, strategic planning and development is undertaken to accommodate a number of visiting Bohras. The masjid is transformed by creating mezzanines on the first storey to accommodate people during the sermons.

Bottom - Figure 7: Masjid Al-Moazzam during the Milad celebration of the al-Dai al-Mutlaq

Furthermore, special routes and programmes throughout the day are prepared to regulate the traffic for men, women and children in and around the masjid complex, and accommodations and travel itineraries are prepared for Bohras coming from different countries. The idea is built on the premise of their global and community scale; the Anjumans work collectively to prepare accommodations for Bohras travelling from various places and the local community prepares the necessary programmes for the hosts. As part of the local community, their mujtama or public spaces are extensively redefined to accommodate the number of Bohras, including spaces for prayer and congregation (Figure 6). Similarly, the Milad or celebration of the birthdate of the Da’i is also celebrated at all masjid complexes throughout the world and their spaces are adorned with lights, banners and gardens to commemorate its significance (Figure 7).

The celebration occurs in Surat and Mumbai, where streets and alleys become procession routes led by high-stepping equestrian units, flower- covered mobile floats and spirited marching bands chanting prayers and hymns. These occasions become an inclusive association by inviting guests and residents to partake in the event or locals are invited to observe from their residential balconies (Figures 8 and 9). This promotes a remarkable civic pride that transforms and adapts within the constraints of the built environment.

Sacred spaces do not only open the internal possibilities to their world, but transform other worlds surrounding them

In American cities, these occasions can bring additional inconveniences such as heightened traffic and security and many cities require a Conditional Use Permit or Events Permit that allow events with an extraordinary number of attending individuals by the City’s consent. These permits are discretionary and these processes force religious groups to revise and remake themselves according to a menu of choices. For example, they may be subjected to limit their activity due to the increased noise pollution or disturbance in the neighbourhood or may require security measures by involving law enforcement officers to regulate pedestrian and automobile traffic.

In this way, religious groups and neighbourhoods work together with local leaders becoming part of a greater public sphere by connecting with different ethnic groups and uniquely adapting to the bylaws of the local environment.

Bottom - Figure 9: The Burhani Marching Band during festivals held in Surat, India

Redefining the Public Realm with Sacred Meanings

In an age of urban sprawl, sacred spaces have the latency to reflect the character and focus of a neighbourhood and city. Although sometimes resulting in conflict, at other times it provokes a significant aspect that pertains to the divine, Godlike or higher power that takes form in social and material spaces. Several intriguing developments emerge as we come to terms with the design of the public sphere with new ethnic experiences. The most significant aspect of the Dawoodi Bohras’ perception and development of public spaces is the collective association of weaving history, faith and belief systems that make up much more than the sum of its neighbourhood and grand buildings. They have challenged – as much as modernity has challenged – land-use schemes to produce environments with a distinct sense of place. The ‘sacred versus non-sacred’ and the ‘seen versus the unseen’ form a spatial reconsideration that marks the role and expression of religion. The Dawoodi Bohras express a rich vocabulary underpinned by their rasam, meaning ‘protocol’, to act in accordance to public spaces prescribed in their courts (Sanders, 1994). Such protocols, including the removal of shoes or performing ablution before conducting prayer on the grounds are the spiritual manifestations of their practices that shape the public realm.

To understand the contemporary city, sacred spaces embody the mundane in a profound transformation that produces dynamic socio- spatial characteristics and new modes of city building. Consequently, the design of the public sphere is reshaped to foster social cohesion and develop meaningful dialogue with the existence of multiple identities. As these spaces continue to develop, they cultivate connections with the rest of the community. Like the Dawoodi Bohra community, sacred spaces do not only open the internal possibilities to their world, but transform other worlds surrounding them in a place that is constantly re-making itself.

Comments (0)