Drive 33 kilometres south west of Delhi and you hit Gurgaon, a city that has witnessed rapid urbanisation. Much like Vashi was intended for Mumbai, Gurgaon promised to be a vibrant adjunct to the bustling metro of Delhi and is now a part of the National Capital Region. The early years saw young families, professionals and business people from other parts of India migrate to Gurgaon in search of careers and a better quality of life.

Before long, and not surprisingly, the city was grappling with lack of proper infrastructure and utilities, frequent power outages and rising crime. The ‘millennium city’ moniker didn’t seem to ring true anymore.

Then Swanzal Kak Kapoor, Ambika Agarwal and Latika Thukral decided to do something about it. ‘I Am Gurgaon’, an NGO started and run on a voluntary basis by a bunch of professionals was set up five years ago. It set into motion a residents’ movement to improve the quality of life in Gurgaon.

“We first moved to Gurgaon 17 years ago from New Delhi and it was wonderful to come to a quiet, small city. I used to live here and commute to Delhi for work. Nowadays our life is only Gurgaon, with the kids’ school and my husband’s office in close proximity. It is a haphazard new city but has its own character,” explains Latika Thukral.

She adds, “Most residents are migrants from other cities of India. We have tried to make this our home and build a life around it. ‘I Am Gurgaon’ was started by the three of us. Suddenly we were all caught in this explosion of the city and we felt the need to save it. It’s easy to crib but today we feel fortunate that we were able to do something to change the situation.”

The NGO is involved in many projects at the local level: cleaning markets, beautifying round-abouts, monitoring cleaning agencies etc. Volunteers in the group are drawn from a talent pool of architects, accountants, urban designers, bankers and media people besides school kids, employees and home-makers. Initially they had no specific agenda except to make Gurgaon more liveable and worked with the civic bodies and the RWA (Residents Welfare Association). They were able to proactively identify projects and a major success story in the initial days was the cleaning up of garbage on the streets.

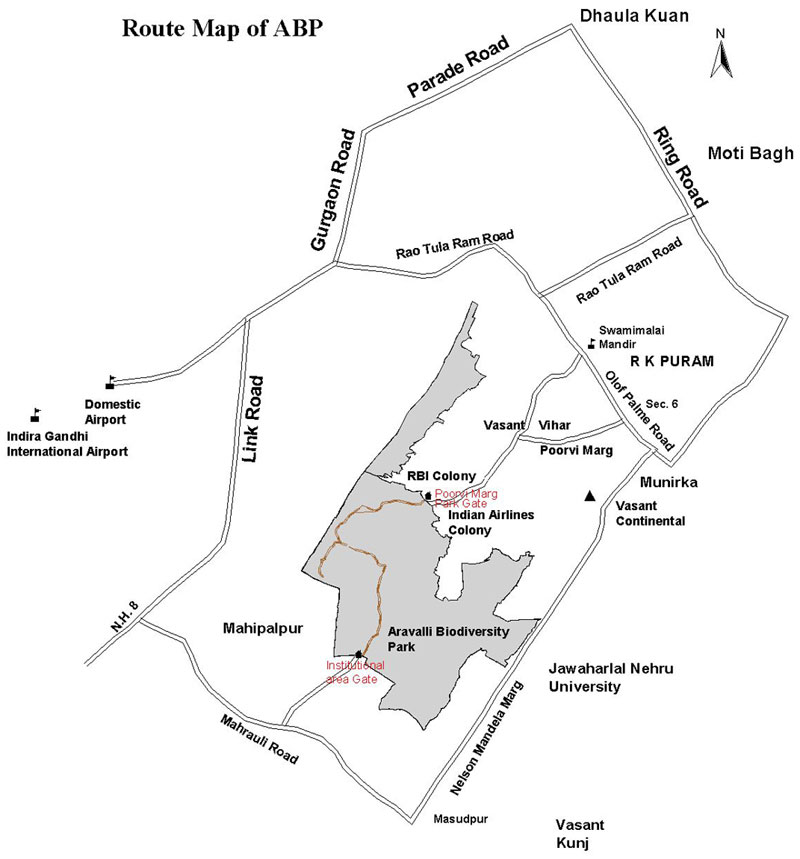

The next big idea was the recovery of parkland at the foothills of the Aravallis. Thukral says, “We were already working with MCG (Municipal Corporation Gurgaon) on the Aravalli Biodiversity Park, when we came up with an idea to plant a million trees in Gurgaon. We needed space to plant saplings and started with this forest.

Gurgaon is a concrete jungle and we felt there was a need to create green spaces.

We reached out to corporates and with their help we started planting saplings. The journey has been a struggle but today it is worth it all when you see the energy and involvement of people, corporates and citizens alike, and all because they want more green space in Gurgaon.”

So what does it really take to convert 600 acres of barren and misused land into a vibrant, lush and eco-friendly environment that is home to over 4000 varieties of flora and fauna?

In 2009, the NGO took over the park from the Haryana Forest Department. The challenge was to restore the park with flora and fauna that is indigenous to the Aravallis.

“We owe Aravalli Biodiversity Park to bureaucrats like Mr Rajesh Khullar (Commissioner, 2010), who understood the benefits of creating a space like this in Gurgaon and helped start the project. Later, Mr Sudhir Rajpal (the next Commissioner) also supported our vision on the revival of the forest,” volunteers Thukral.

Each day poses a challenge: Fences being cut, cattle grazing, organising water and sometimes coping with vandalism. However, dealing with encroachments is the biggest problem in a country where people believe public land is their own. Contrary to popular belief, the ‘grabbing’ mindset is not limited to villagers. Even educated and rich people encroach. For example, the forest touches DLF Phase 3 of Gurgaon where house owners cut the fence and encroach on bio-diversity land to make their private gardens.

“Why would you even touch a piece of land that does not belong to you?” asks Thukral, annoyed. The Gurgaon administration has helped fence the entire park and solve the many encroachment issues with the bordering villages. While the struggle continues each day, the Aravalli Biodiversity Park has been re-forested thanks to the leadership of Latika and her mates.

With a strong network of people who are collecting seeds from the forests of Udaipur, Satpura, Rajaji and Kumbhalgarh National Parks, the Biodiversity Park can proudly say that it is the biggest nursery in the country for Aravalli species. There are two nurseries working with corporate funding and the saplings are planted at the park. The Aravalli Biodiversity Park is also hopeful of becoming one of the largest bird sanctuaries in the state.

So how does a successful banker turn her back on a career to work for the benefit of her community?

The frustrations are plentiful. Says Thukral, “I don’t know how many times I’ve wanted to just run away. But we are at a stage where we cannot leave this project. We still have a lot to prove to the administration and people to show them that this kind of public-private partnership works. We are answerable to every corporate for the funds collected. We don’t like being called activists as we believe we are all part of the system and have to work together for things to change.”

For her, the inspiration is the people who reach out in support: corporates who have continued to commit to the cause over the last five years, older people who stop and confer blessings, residents who start taking ownership for the project, school children who visit the park as part of their curriculum and, in fact, all the spouses and kids who volunteer, support and enable the process of change. It motivates them to see the huge expanse of land and the saplings growing, knowing that it’s only a matter of time before Gurgaon has a forest.

Comments (0)