In the past decade, discussion about pedestrian comfort in public spaces has centered largely on safety. There is another aspect that is often seen as secondary: beauty. The provision of narrower streets, street trees, adequate sidewalk width and street-side amenities do create a pleasant experience for pedestrians, but there is a deeper aesthetic to public space that should be part of the designer’s palate. If we study urban design at the time when motorised vehicles were just beginning to enter the picture, we come across the debate for the preservation of civic beauty expressed through tactility, texture and enclosure and the need to accommodate vehicles.

There was a great discussion between Camillo Sitte and Joseph Stübben around this issue in the late 20th Century. Sitte was largely concerned with the beauty of the built environment while Stübben believed that the oncoming wave of vehicular traffic must also be considered. Sitte didn’t warm up to the idea and felt that civic art was compromised by vehicular interventions. An architect and civil engineer, Stübben was keenly aware of the needs for infrastructure in urban planning, both for the purposes of sanitation and multi-modal accommodation. He believed that beautiful public spaces could coexist with more mundane needs.

At the time, and for about 150 years beforehand, it was recognised that enclosure was a fundamentally important consideration in framing the public realm. Building height to building separation was most pleasing for the pedestrian at a 1:1 ratio. 1:2 and 1:3 were best for the appreciation of architectural detailing and the enjoyment of the ensemble of buildings. 1:4 and 1:5 were appropriate for squares and plazas. The perception of spatial enclosure evaporated at 1:6 and greater. In addition, narrow lanes, vista formation and landscaping enhanced the experience.

These elements, said Stübben, allowed an appropriate mix of multi-modality while preserving those important aspects of civic art one has seen for millennia.

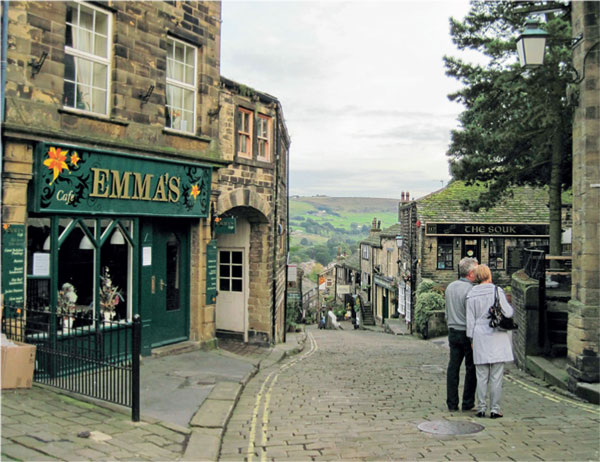

Modern urban design practice for walkable, diverse and mixed-use projects rarely include sidewalks and pavements made of stone or brick, sidewalks at or slightly above street grade, bollards to prevent random parking, narrow lanes in a yield condition, a variety of visual termini (concave, convex, terminal vistas, etc.), buildings or trees encroaching into the street and so on. Part of the reason for this is expense, emergency vehicle and service vehicle access or the provision of utilities. All of these, however, can be overcome with thoughtful design. As illustrated below, those who are enjoying an espresso less than a couple of feet (60 cm) from the street will not be bothered by annoying traffic and the noise. Notice that all the elements described above are present here. This is actually a pedestrian dominant environment.

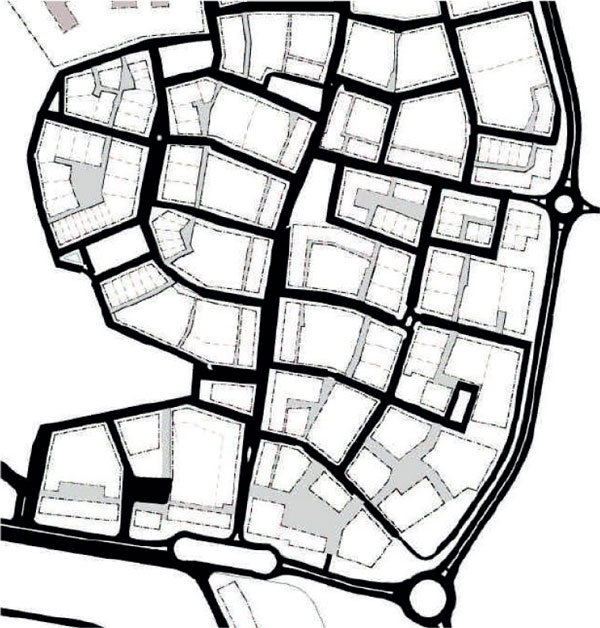

I’ve had the good fortune to work on several projects that incorporate medieval techniques. In fact, one of the first was being tasked to design the thoroughfares for a project in Guatemala called Cayala, designed by Leon Krier. He established the general block layout and I went from street to street trying to introduce unique characteristics for each one.

The plan above represents the area I concentrated on. One of the first things I noticed was that the alignments of the streets were fairly regular and not like a squirrelly goat path. I was a bit alarmed because I knew that I had to figure out how to become deeply nuanced in the treatment of the design to make this work and not have Leon look at me as if I was a moron. Having studied 18th and 19th Century urbanism, however, I felt confident that I could remember details of those great streets and apply that knowledge to this project.

Not only did the design come together nicely, I wrote a chapter in my forthcoming book about how I formulated taxonomy of medieval types to present the reader with the more common configurations. They are itemized as follows:

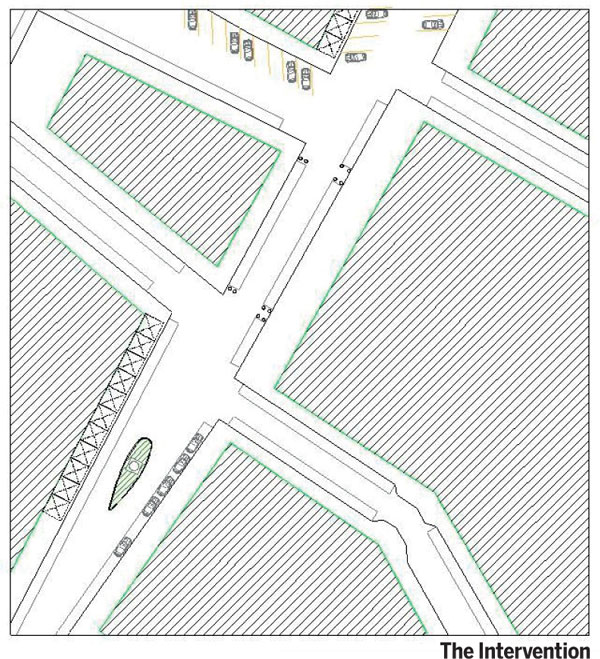

The Intervention:

Intervention is the extension of a building into street space. This is a device used for particularly important civic buildings. A town hall, church and museum are examples of buildings occupying and intervening into the street. This is also an opportunity for the use of a higher level of architectural elements and order.

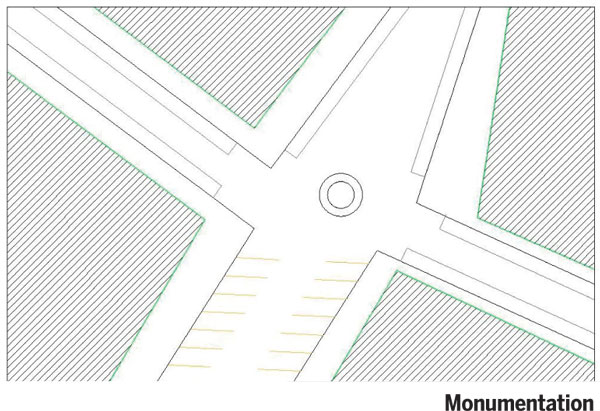

This example also includes monumentation shown in the small island in the street below the intervening building. The monument was placed so that the front of the civic building was visible in almost all of the street space. Vehicles and pedestrians would not have an obstructed view of the front of the building (see Monumentation, below).

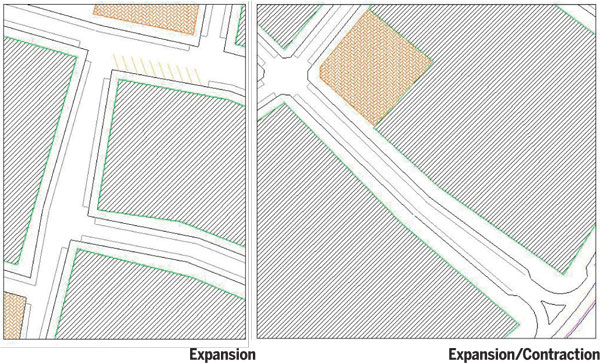

Expansion/contraction: This type of street has a kind of diaphragmatic breathing of the public space as it expands and contracts. It is useful in a number of ways including the provision of distorting and exaggerating the perception of a vanishing point. The play of sunlight and shadow on the street creates visual interest in its subtle variety. The asymmetry of the building placement affords the observer a variety of perspectives and an appreciation of mass, scale, articulation and ornament as the width-to-height ratio changes along the block.

The Jog: Notice how the break points in the adjacent blocks are offset. The street can be designed in one of two ways: parallel to the block face at a uniform oset with varying street width or designed with a consistent curb face width. The former creates interest within the street and the latter creates interest along the sidewalk.

Depending on the width of the sidewalk, there could, in this case, be opportunities for sidewalk restaurant seating, building frontage variation or placement of street furniture such as kiosks, bench clusters, planter boxes or other such devices.

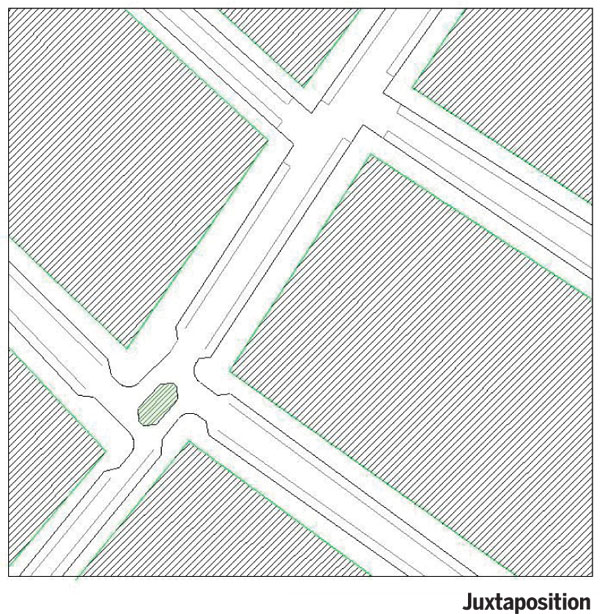

Juxtaposition: The close oset of two streets forms a terminated vista for both streets. These types of intersections may exist within a portion of the neighbourhood that does not need a direct connection to the centre. They exist closer to the edge. The intersection with fairly low traffic volumes may simply be designed as shown in the upper right portion of the exhibit. If traffic volumes are such that peak hour gaps are reduced to four seconds or less, then the traffic must be controlled in a manner shown as a small turbine square. Design vehicle turning movements must be analysed for this type of intersection. It may also serve as a visual terminus from a more travelled thoroughfare indicating that there may be a place of varying building use or interest.

Monumentation: Monumentation is a celebration of a communities’ love of art, aspirations for the future or respect for its history. It commonly takes the form of a statue, obelisk, small fountain, flower garden or other traditional complements to the civic realm. It may be placed directly in the street without an excessive use of traffic control measures like bollards or islands. It should be robust enough to indicate to the driver that it is a formidable object and caution must be employed in negotiating the intersection. It should be placed so that it provides visual terminus from several streets or paths. A statue or work of art in such an important place should not be a manifestation of an artist’s personal expression or private exploration; it should express respect for the community in a dignified manner.

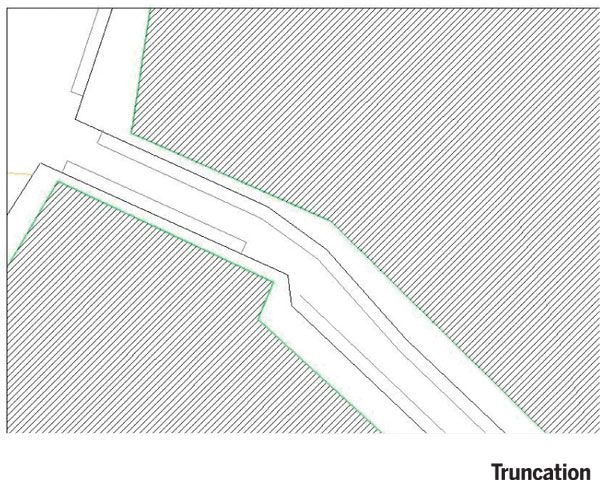

Truncation: A radical intervention of a building into the street space creates a remarkable opportunity to observe a special architectural feature of the building. The street loses its parking at that juncture as the space is pinched. This is a place that becomes almost pedestrian dominant and may become a gathering place depending on the adjacent building use. Perhaps this will become a great location for a café, newspaper store or a place that is delightfully discovered by a visitor.

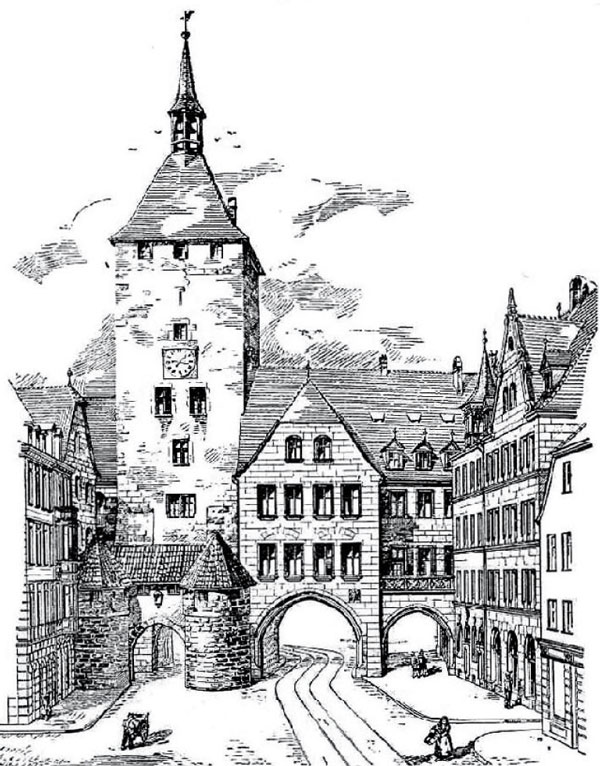

Occupation: The occupation of the street by a building is an extremely powerful device. This is an entry to a high street, neighbourhood, town or city. It can also be a landmark that provides a clear demarcation of an urban centre. A powerful addition to this ‘frame’ is having something of great interest terminate the view through the occupied arch. This can be another building, a park, a statue or monument or some other piece of civic art. This technique can be understood more thoroughly by examining the Tragic Scene of the three theatrical sets drawn by Sebastiano Serlio in his Books of Architecture (1530). The view framed by the arch is as important as the intervention of the buildings themselves.

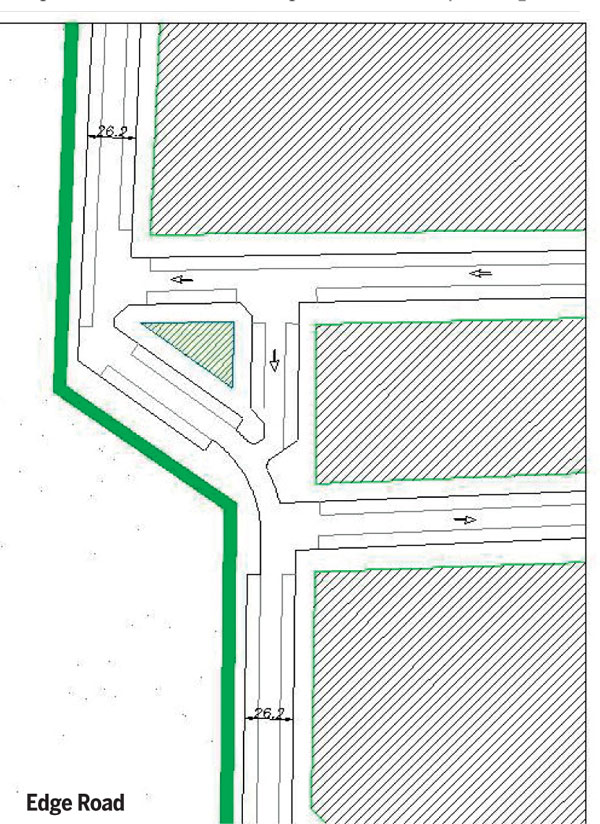

Edge Road: An edge of a medieval town is typically well defined and somewhat abrupt. It frames and abuts an agricultural or natural landscape. It provides an opportunity for people to stand on the boundary between the works of man and nature. It is similar to an esplanade in that sense. A walk of adequate width should follow the edge and provide places to sit. The street should be calmed to a point where design speeds fall closely to 15 miles per hour [24 kph]. This helps ensure that vehicular noise does not interfere with the experience. This is also a good location for the extension of small urban parks that lead the eye from the interior of the neighbourhood to its edge. Conversely, the park brings the natural landscape through a finger of green formality into the neighbourhood.

The above examples are intentionally simple. They do not include a gallery of photographic evidence for precedence. This is an attempt to develop a lexicon of street types that may be introduced into the engineers’ vocabulary. There are a significant number of examples of medieval street types in the United States from New England villages to mountain villages in the Sierras. These streets work quite well as multi-modal environments, traffic calming devices and aesthetic configurations of the public realm. By simply observing these places, it becomes evident that traffic moves slowly and deliberately thereby allowing somewhat constrained geometries.

The biggest problem we encounter with having these types approved and built lies with the fire department. There are a number of ways that these obstacles can be overcome, but two things need to be agreed upon:

1) The fire department operations people must be trained to deal with a constrained environment. Urban departments in large cities have firefighters that are more flexible and resilient. Suburban types will outright reject the proposal and have a good laugh that you even thought of this. Volunteer fire departments in small towns could be agreeable.

2) There must be a strong City Council, City Manager and support sta. Without political determination this will never get done. Also, if the fire department is independent of the city, they will never approve of this.

In conclusion, it is important for us to refocus on comfort and beauty in street types that are not only attractive, safe and encourage non-motorist activity, but evoke heartfelt mental imagery of places that fully accommodate our highest aspirations, history and sensory awareness. They should be streets that create a ‘place’ and are wed intimately to their status alongside plazas and squares of classical and timeless beauty.

Comments (0)