The historic core of Guangzhou (formerly Canton), China’s third largest city, is rapidly transforming due to housing and development pressures. Over the past decade, many of its narrow traditional lots, originally occupied by modest two- and three-storey dwellings, now have buildings more than four times as tall. These are typically mid- and high-rise apartments arranged around a central circulation core, with units getting light and air from one or, in the case of a corner, two sides. The open space between these tall new buildings blatantly contradicts the scale and experience of its traditional predecessors.

Some parts of this historic core designated as conservation areas, however, continue to be a living repository of traditional Cantonese urbanism, housing and community space. Guangzhou’s traditional urban elements and patterns are clearly evident here in an intricate network of waterways, lanes and streets. The space between buildings continues to nurture multi-generational rhythms of urban life and Old Guangzhou’s traditional street-urbanism thrives in these places through distinct and identifiable street types and their components.

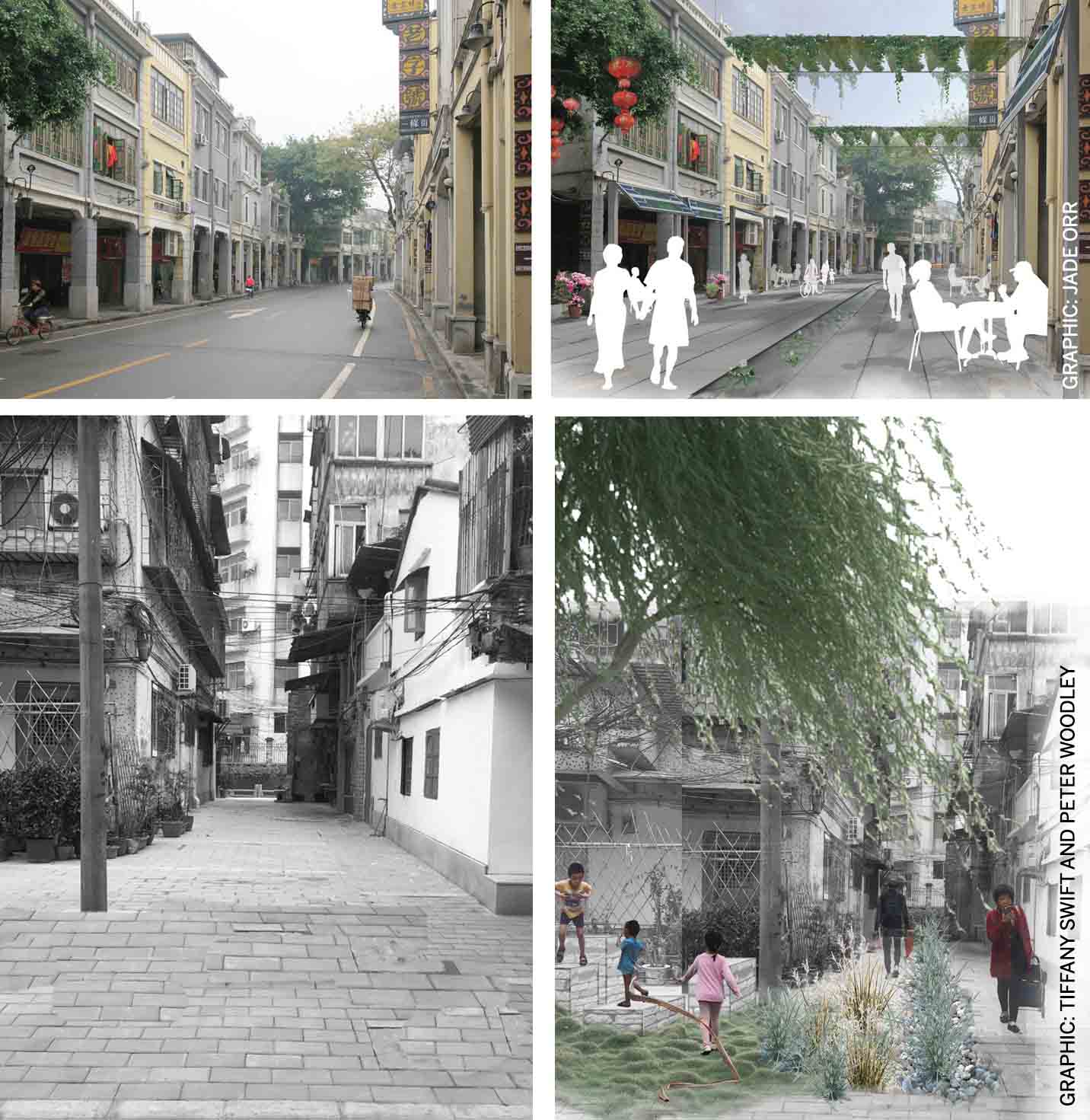

This essay looks at the formal and behavioural aspects of two such types: Qilou – arcaded streets lined with shop-houses, and Hong – intimate lanes that serve as circulation paths and community spaces. These two elements supplement the generic street grid of the district adding to the diversity and rituals of diurnal and seasonal urban life. As such, these elements offer distinct, culture-specific ideas on street design, housing, urban development, climate-conscious urbanism and community life that can find potent applications in contemporary urbanism for Guangzhou, China, and beyond. Our study focuses on the Qilou and Hong within the Liwan District area of Old Guangzhou, around the recently completed Museum of Cantonese Opera, an ambitious attempt by the Guangzhou government to revitalise this historic area of the city.

|

Bottom: (From left to right) Qilou in Guangzhou in the 1940s; Qilou in 2014; Completely intact Qilou streets today |

Qilou

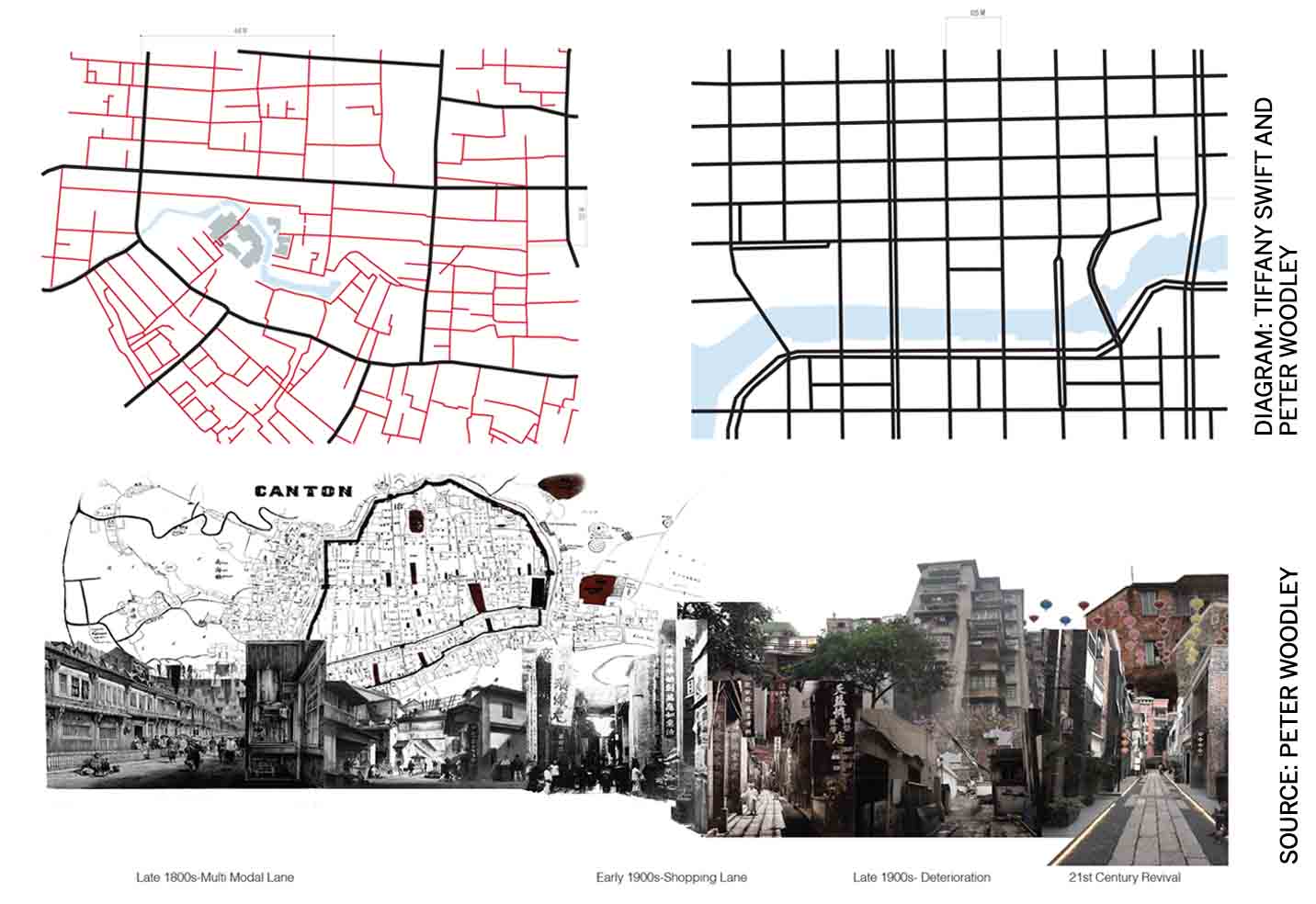

It is speculated that Guangzhou’s Qilou streets originated from the shop-house prototype introduced to Southern China during trade exchanges with Singapore. The popularity of the shop-house increased as it allowed people to both live and conduct commercial activity near Guangzhou’s ports. During the 20th century, with automobile increase, the government began widening Guangzhou’s streets and the shop-house model was designed with multiple Cantonese architectural styles creating the Qilou streets seen in Guangzhou today. Most appeared in Southern China in the early 1900s, proliferating in the city between 1910 and 1930. They were built as arcaded streets to separate pedestrians from vehicular traffic and also to create a sheltered zone in the rainy climate. Qilou development continued until around 1949 when the Communist Party came to power in China. Qilou were now seen as symbols of capitalism due to their Western-style facades. Some were destroyed while others were kept intact due to a looming housing shortage. These remaining Qilou were subdivided into multiple ownerships, leading to dense living conditions and the arcaded spaces originally meant as largely pedestrian space began to get appropriated as a place for everyday community activity.

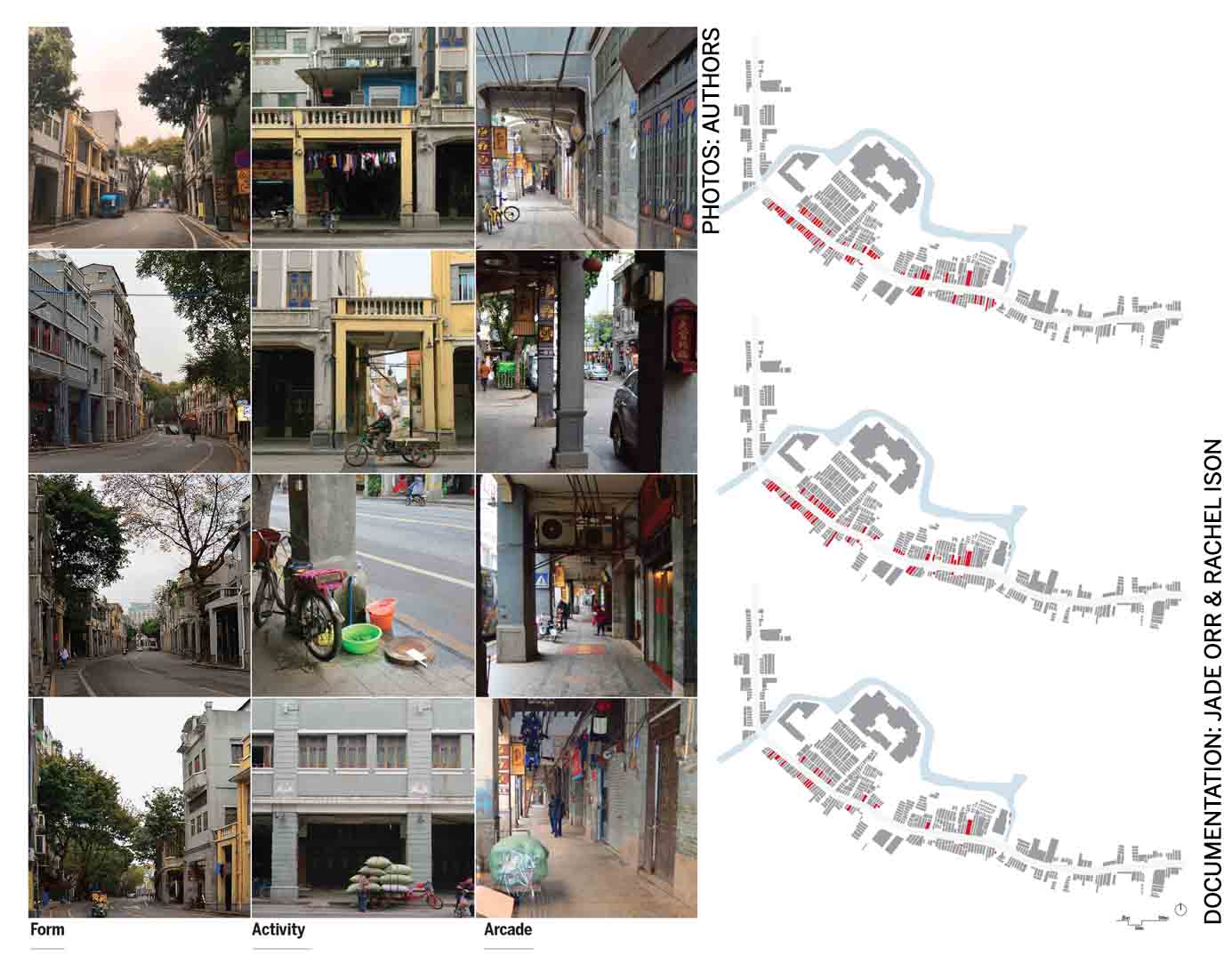

Enning Road is the most conspicuous Qilou in Guangzhou’s historic core, topping the Qilou preservation list in the 2008 redevelopment plan for the district. This plan would have turned Enning Road into a shopping mall with retail and office buildings, but the residents of Enning Road came out in protest and succeeded in changing the plan’s intentions. Today, Enning Road remains intact in its original form and architecture, markedly different from its surrounding streets. It is nine metres wide from building face to building face, accommodating two vehicular lanes and two small bike lanes. The sidewalks beyond the building face are almost entirely covered with arcades that typically extend about three metres to the street edge. The arcades are continuous, except where lanes meet the road and where occasional trees break the rhythm of the columns.The buildings typically range from two to four storeys. Enning Road’s distinct form as a sparsely planted, curved, arcaded ensemble of continuous narrow buildings gives it a unique character within the district’s surrounding verdant streets.

Qilou were now seen as symbols of capitalism due to their Western-style facades

But Enning Road is a semi-vacant street. Our study of the Enning Road section between Duabao Road and Baohua Road, in front of the recently completed Museum of Cantonese Opera, indicated that among a total of 125 shop-houses on individual lots, 51 were vacant on the street level, 49 were vacant on the upper levels and 21 were completely vacant on both levels. While the Enning Road redevelopment plan – that threatened the displacement of its residents – was ultimately stopped, it caused many to preemptively move out, fearing their homes would be destroyed. This left a large amount of vacancies. Today, a predominantly low-income population inhabits Enning Road, with a dominant elderly demographic and others who work along or frequent Enning Road largely reside along proximate streets and lanes.

Left column – Form, Middle column – Activity, Right column – Arcades Top, Right: Enning Road vacancies. Top: Street/Shop level vacancies with active residences above; Middle: Upper/Residential level vacancies with active shops below; Bottom: Buildings vacant on all levels |

Yet, Enning Road is a distinct community with daily and seasonal rhythms. In the absence of heavy pedestrian activity, food preparation, informal seating and communal tea-drinking occur in the arcades. Clothes are hung to dry between the arcade columns, while laundry and bike deliveries happen at the sidewalk edges. In the evening, entire families come down from the residences above to their shops below and children are seen doing homework and playing games within the shop itself. Such patterns are vivid reminders of the rhythms these shop-house streets traditionally sustained: In the hotGuangzhou summers, the windows and shutters of the residences above and the arcades below would all remain open to ease air flow.

Early morning activity would begin in the residences, and flow downward to the shop area making it ready for the day. The arcades would team with customers, gathering in numerous eateries and snack bars. By late evening, family members and children would come down to the shop area that would now transform into a social space extending into the street. Temporary furniture and game chairs would be set up within and beyond the arcade for meetings and tea, until the late night hours. In the rainy season, the arcade would become the primary social space, shielding residents from Guangzhou’s ample rain. Many such rhythms are still evident today in sporadic forms and the dense afternoon and evening commercial activity in the surrounding streets continues to remind one of the rich urban life that must have occupied this street not long ago.

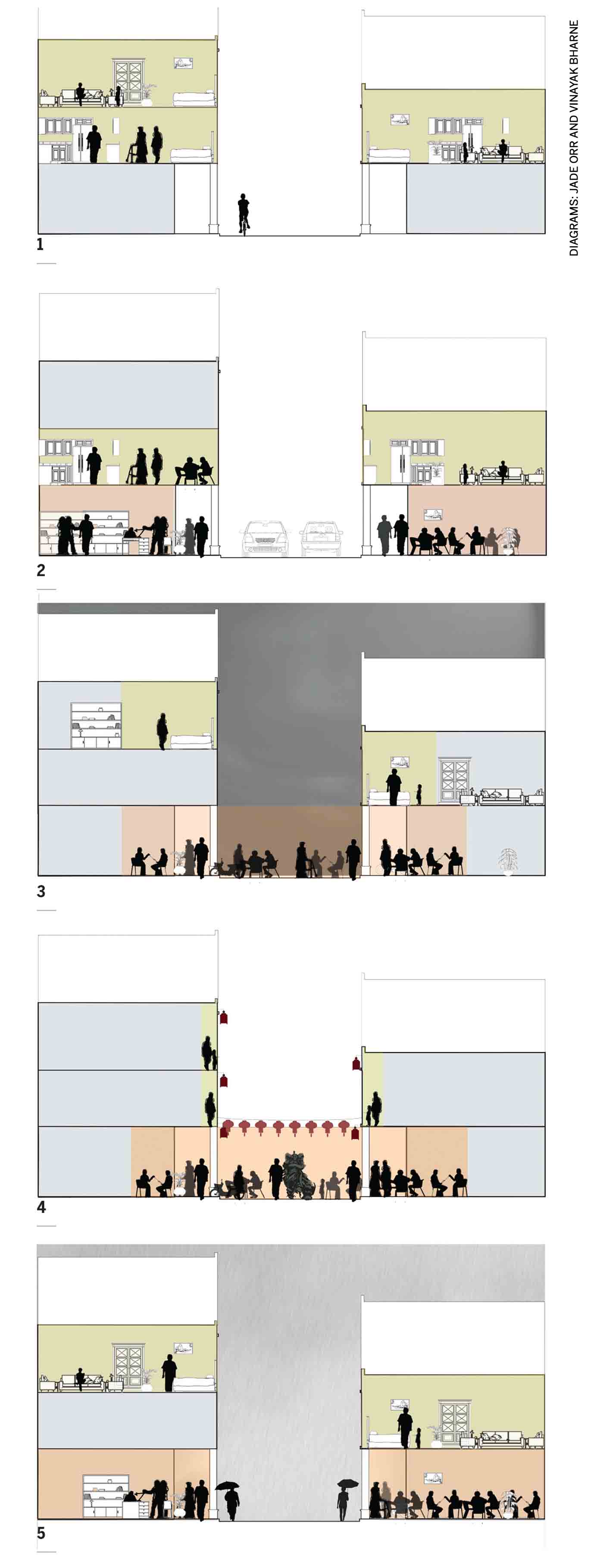

From top to bottom: 1) Early morning activity in the residences above while the shop remains closed. 2) Mid-day activity in the shop area and residences above. 3) Late evening activity in the shop, arcade and street. 4) Street space as setting for festival. 5) Late evening activity in the arcade area during rains. |

Hong

If the Qilou represent distinct places within old Guangzhou’s generic street network, then the Hong are its most ubiquitous structuring urban element. These narrow lanes were developed before the presence of vehicular roads in the city. They were originally circulation thorough fares, developing gradually into a variety of social spaces. With increasing traffic demands, new arterials were built segregating the continuous lane network into large identifiable neighbourhood precincts, each with an internal network of lanes. Today, principal lanes run perpendicular to arterials, each marked by a walled gate, clearly identifying the precinct’s boundaries. These principal lanes are intersected by secondary and tertiary lanes. Together, they form the district’s main circulation routes for pedestrians as well as bicycles that prefer the lanes over the arterials as safer and shorter routes between various points.

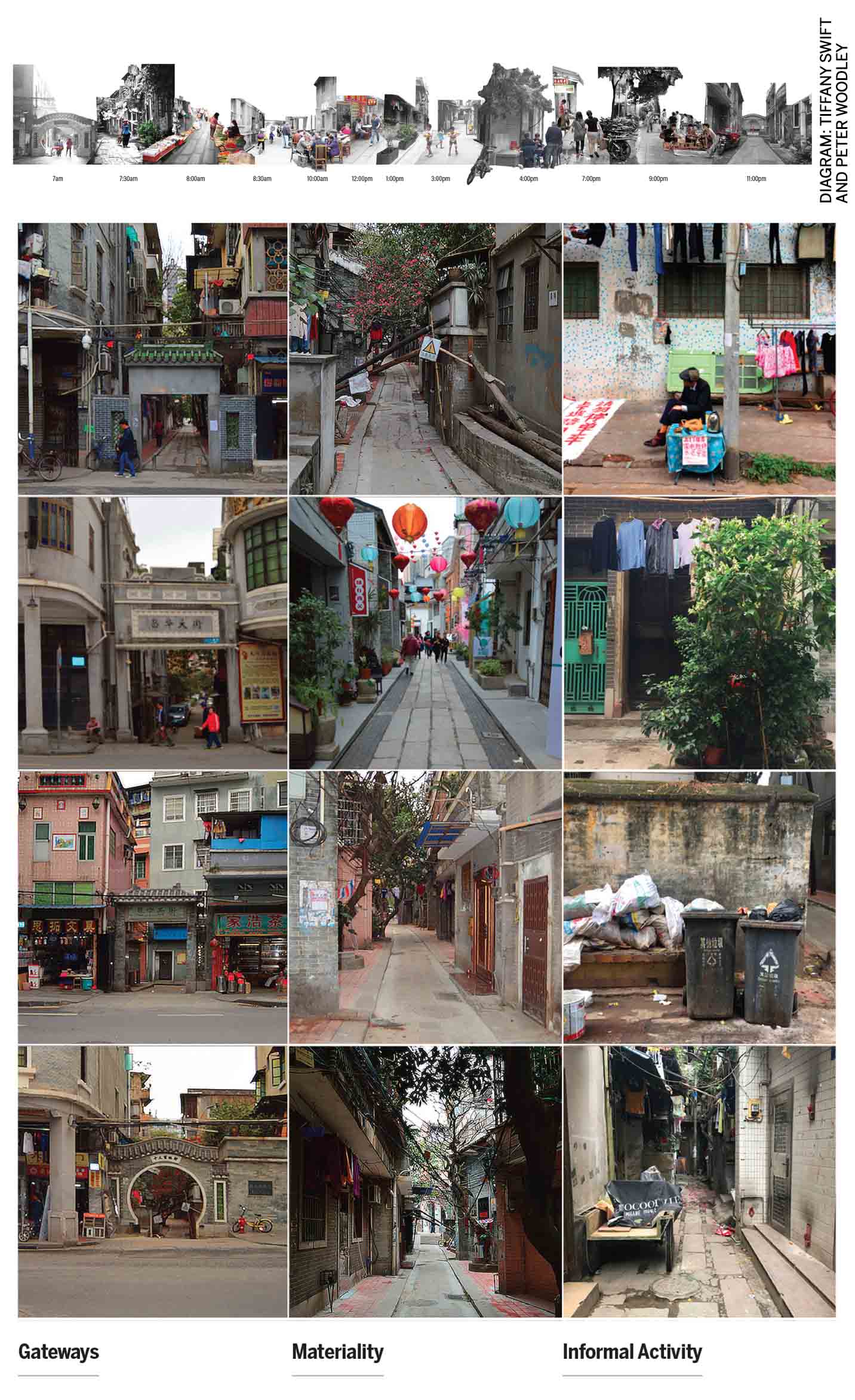

The Hong range from around 2 to 4 metres in width. They were historically paved with mostly pebble stones and mud with no formal sewage system and this contributed to significant flooding and water accumulation during the heavy rains. Today, most are paved with large stone pavers and some also have underground utilities. Many Hong have succumbed to development pressures, with mid and high-rise buildings filling their narrow traditional lots, significantly changing the spatial proportions and sunlight in these narrow spaces. Some Hong have become service alleys for the tall, dense buildings, occupying post boxes and spaces for drying clothes. Some in turn have become social spaces for the vertical community, planted with occasional trees and shrubs. Others that connect to major arterials have become informal neighbourhood street markets lined with temporary shops selling fish, groceries and daily needs. They may not be in the best of physical condition, but these Hong still remain active as rich micro-communities separated and sheltered from the bustle ofOld Guangzhou’s commercial arterials.

Bottom: Collage overviewing the development and deterioration of lanes in Guangzhou |

Challenge

Guangzhou’s traditional urbanism was a rich street-urbanism. Unlike the European model where plazas and squares of all shapes and sizes were the primary spaces for social life, in Guangzhou, as in most of China, it was the street and its variations that became the fundamental prototype of civic and community life. That these elements and patterns have survived the onslaught of modernisation is evidence of their cultural resilience. The Qilou and Hong discussed above thus represent significant cultural artifacts worthy of care and conservation.

The challenges to achieving this are not insignificant. While residents of Old Guangzhou continue to retain traditional patterns of life, ongoing modernisation within the core, even with the best intentions, can land up being disruptive. For example, several lanes between Enning Road and the Museum of Cantonese Opera were recently revitalised into a creative artist’s community and workshop space that was meant to serve the community. While this new development has taken cues from the traditional aesthetic and is designed by a sensitive and skilled architect, the newness of the restored and reused buildings has changed its reception for the low-income residents of Enning Road.The space is utilised by younger residents of the surrounding community, but it was met with contention by much of the Enning Road community, that felt it strayed too far from the historic character of the traditional street. Another challenge is the vacancy within Enning Road’s shop houses. How does one bring new residents to this place without gentrification or current community displacement? This is as much an issue of public policy as social justice. On the one hand, Enning Road’s historic shop houses need urgent care, occupancy and attention. On the other, their restoration can come at the price of changing its economic status.

The Hong in turn have their challenges.In neighbourhoods dominated by a senior demographic, residents do not like to walk too far from their apartments and the spontaneous and ad hoc takeover of Hong spaces has not always resulted in the best outcomes. Some Hong have become primary social spaces for the elders but others – as seen in the neighbourhood east of the Cantonese Opera Museum – have been appropriated as areas for garbage and refuse. In this neighbourhood, several of the four- and five-storey buildings are also not in very good condition and some are half empty. The Hong between such buildings have remained relatively neglected and deserted for years.

Bottom: Hong, the contemporary condition. The first column details the gateways that mark the entries to the lanes leading from Enning Road. The second column looks at the different forms and materiality of lanes in this area and the third looks at the informal activity that takes place in the lanes currently |

Bottom: Potential enhancement of Hong to create a bioswale, filtering water from the lanes before it enters the overall water system in the canals, while increasing green space for the community

Prospect

The Qilou and Hong are not isolated urban elements. They are, combined with the district’s streets and waterways, a continuous open space network that is simultaneously ecological, social and cultural. If they can be read as such, then their possibilities can far exceed their linear understanding as social spaces alone. Streets and lanes located close to the waterways, for instance, can be designed to regulate storm water into the channels. The district’s verdant streets with mature trees – thanks to the heavy annual rain – can be understood as a continuous ‘forested’ landscape separating individual neighbourhoods. Within the neighbourhoods, select Hong themselves can be strategically planted to generate temperature and humidity variations as required. And within this ecological network, the Qilou can serve as unique destinations characterised by their eclectic buildings and arcades. Amidst Guangzhou’s ongoing development pressures and within the realisms of China’s administrative and real estate workings, it might not be entirely possible to conserve OldGuangzhou’s historic fabric to a degree that might adequately celebrate its past. Old dwellings will continue to be replaced by bigger and taller buildings and economic and demographic shifts will also perhaps transform the experience of the district over time. But within the trajectory of such changes, conserving and reclaiming the district’s traditional open spaces as a continuous network of multifarious ecological and urban elements will not only have transformative positive effects on the environmental and social dimensions of the city, but also open a far more pragmatic means to mediate conservation and new development. It will re-establish the diminishing links between Guangzhou’s past, present and future. Old Guangzhou needs to reclaim its Qilou and Hong as parts of larger open space ecology, as well as an enduring heritage.

This paper emerged from findings from a graduate landscape architecture studio in Spring 2017 at theUniversity of Southern California in collaboration withSouth China Agricultural University. We would like to thank all the students and faculty from both universities for their participation in this effort.

Comments (0)