Bottom: Moore’s Law

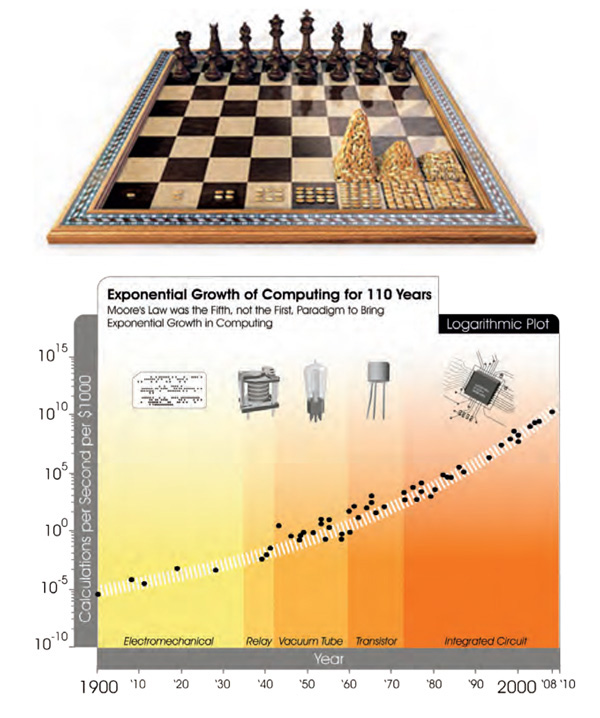

The story goes that long ago the inventor of Chess was invited by the king to sell his idea to him. The king was ready to reward the inventor richly. The inventor agreed to sell the game to the king on the following condition: the king would have to lay 1 grain of rice on the first square of the chess-board, 2 on the second square, 4 on the third square, 8 on the next and so forth till all the 64 squares were accounted for. The king was surprised by this modest request, little realizing that the multiplying effect would result in a gargantuan end result.

Exponential Growth

The fact is that the king suffered from a linear brain. His and our brains have evolved at a time when things hardly changed during one life span. In such times, a linear approach to numbers was effective enough. However, since some time now, technological developments are not changing linearly but exponentially. This exponential growth is most visible in the ICT (Information and Communications Technology) industry. Moore’s Law states that the power of a computer has been doubling every year (See illustration). Computers are getting smarter and in turn are making machines, which can make even more smarter computers.

In various sectors, this exponential growth has been fueled by ICT and results in the disruption of the traditional industry. The industry is being redefined by newcomers thus leading to plummeting prices and democratization of services. Examples abound in different sectors.

In the field of photography, traditional leader Kodak (with 140,000 employees) has made way for new players like Instagram, in the bargain making photography for the user virtually free.

Similar examples can be cited in the music industry, encyclopedias, translators, video stores and in journalism. All now dominated by new players such as Spotify, Wikipedia, Google Translate and Netflix. A true democratization of virtues previously available only to a privileged few.

ICT And Mobility

As ICT makes its way into the world of mobility, both the vehicle and the system that organizes mobility are undergoing turbulent changes. Packed with computers and ICT, the smartest cars of today produce more data than any other consumer product and have more computing power than a small passenger jet aircraft. And by sharing its information with other cars, new technical possibilities are being created with disruptive effects in the sector of mobility, which will be similar to those in other sectors described above.

This article tries to give an insight into the future of mobility when the disruption takes place.

Human Need for Mobility

In a study at MIT in 1998, Andreas Schafer and David Victor demonstrated that an average person spends 1.1 hours per day travelling. This, according to them, has been the pattern since prehistoric times. Regardless of the period in history and other societal conditions such as wealth or gross domestic product, this seems to be the amount of time we use for mobility.

Thus, mobility is not only a necessity and the means to a goal but a goal in itself.

Pros and Cons of Mobility

While mobility has brought prosperity and freedom and improved the quality of life, it has also certain built-in disadvantages. Worldwide, it is estimated that 3-5% of our Gross Domestic Product is lost due to accidents, environmental pollution, energy consumption and pressure on limited space. In other words, the economy would perform 3-5% better if traffic polluted less and caused fewer accidents and less congestion. This seems to be within our grasp in the future with the use of ICT in mobility.

Safety

Accidents are responsible for a major part of the total loss in mobility. In recent years there has been a sharp decline in the number of casualties and wounded in the Netherlands and while this has been due to various different measures, the safer car itself has played an important role.

Safety cages, airbags and other techniques have increased chances of surviving an accident. The car industry is focusing more and more on technology that significantly helps avoid accidents. This tech is called ADAS: Advanced Driver Assistance Systems. Complementary to the ‘Autonomous Vehicle’ (in simple terms, the driverless car), the development and use of ADAS will lead to a sharp fall in the number of accidents. In fact, Volvo has claimed that from 2020 a new Volvo will kill no one since all their new cars will be fitted with a variety of sensors and actuators. Other manufacturers too have similar goals. In fact, with the possibility of cars becoming inherently so safe, more attention will have to be paid to the safety of other road users such as cyclists and pedestrians.

Environmental Pollution

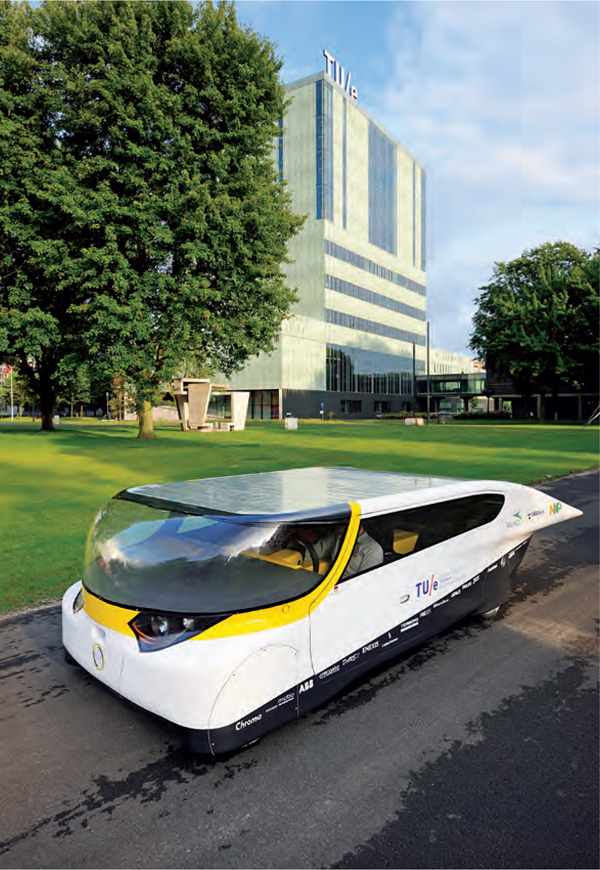

With great advances in more efficient machines and with scrapping programmes in effect for older polluting vehicles, it can be anticipated that environmental pollution due to vehicular mobility will decrease over time. The real challenge is in reducing CO2 emissions. As long as we continue to depend on fossil fuels for our total energy supply, the mobility sector will be among the last to switch over to other renewable fuels. The switch to renewable fuels in other industries is much easier. Total independence from fossil fuels will only come if we can tap the unlimited and renewable solar energy. The massive reduction in the cost of solar cells in the last few years is promising. The enormous power of solar cells has recently been demonstrated by Stella, a solar family car built by students from the Eindhoven University of Technology. On an average day Stella produces more energy than it would consume on an average daily drive.

As renewable energy in due course will most probably become available in the form of electricity, electric vehicles will play an important part in urban mobility.

Road Congestion

In cities it is the limited road space that leads to congestion. However, new developments in ICT- led solutions are on the way. By informing more and more drivers through peer-to-peer information on the status of traffic, road space will be optimally used and congestion reduced. The expectation is that in the near future almost all the new vehicles will be fitted with Tom Tom, Google or Apple information systems leading to more efficient use of the limited roads. This overview of the traffic situation available to all the participants will lead to more efficient usage of the infrastructure by better distribution of traffic geographically and in time (by participants adjusting the timing of their travel), the role of the government will change from managing traffic to facilitating it.

Traffic will effectively become a self-steering system of well-informed individuals. Seen in the context of the earlier conclusion that cars will neither crash nor pollute, traffic jams will become more manageable. The only constraint, which will remain, will be that of limited space in the urban context. But here too ICT and data-based services could provide a revolution by linking supply and demand more efficiently. Car-sharing and ride- sharing apps such as Blablacar, Snappcar and Uber are triggering the change.

By increasing the number of passengers per car, the mobility will increase and the cars will be used by more travelers over longer periods of time, thus decreasing the need for parking facilities.

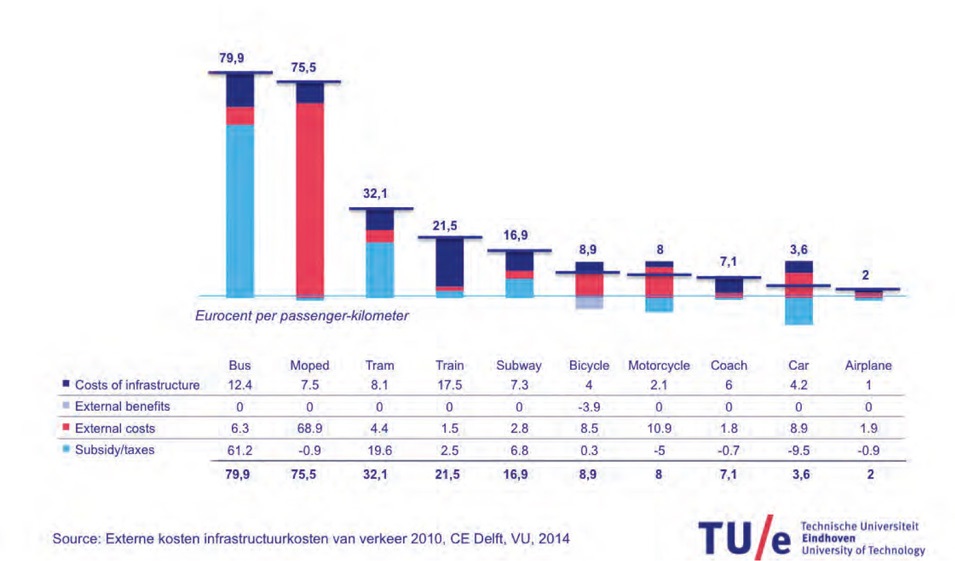

By optimally organizing the ICT-led supply- demand services, the cost of mobility will decrease and for door-to-door transport the car will, even more than now, prove to be unbeatable (see graph above).

It goes without saying that besides the improvements achievable in vehicular mobility, parallel improvements will have to be made for cyclists and pedestrians. But ease of mobility must have as its goal the creation of an urban context facilitating people to meet and interact with one another. Depending on the size of the city other forms of public transport will need to be offered such as buses, trams or metros.

Reduced Role for The Government

The future is likely to be one in which disruptive services for mobility will be offered by private players. These services will come in spite of or despite government interference. Examples are services such as transport company Uber, traffic information service Tom Tom and the multi-modal route-planner Google. Now even Twitter is being used to influence mobility. None of these resulted from a government initiative.

While predicting the future of urban mobility remains a difficult task, one thing is certain, the dawn of the exponential age suggests that changes will take place at a very fast pace. Triggered by ICT, whenever disruption does strike, the impact will come faster than expected.

Comments (0)