The importance of trees for us all hardly needs to be elaborated. Our forefathers venerated them and cultures around the world have eaten fruits from their branches, and some have even used trees to build houses. In present times, with climate change writ large, the usefulness of trees to sequester carbon is invaluable. Trees also make cities more liveable by reducing the urban heat-island effect in times when the global temperatures are set to rise by 1.5 to 2 degrees C.

In spite of this, the pressures of urbanisation, and particularly high-density urbanisation in Indian cities where densities of FSI (Floor Space Index) 3.5 or more are being realised, has meant that trees by the hundreds are being cut to build real-estate and infrastructure.

Yet, in two of our large projects – one in Bengaluru and another in Vadodara – we have used the following design-strategies to protect a large number of old and many monumental trees, besides planting hundreds of new ones.

Analysis: In both of these projects the design work started with a thorough analysis of the trees on the site (quantity and quality) including the gradient on the site and the contours on which the trees had grown.

Creating Public Spaces: In the urban-design vision, the location of important trees was a major guiding factor in deciding where to locate the network of public spaces. By assigning the trees to such public spaces, the possibility of retaining them increased. The landscape design of these public spaces further highlighted the presence of these trees.

Locating Infrastructure: The vehicular infrastructure, which uses up large tracts of land and which with its rigid logic of efficient vehicular movement often leads to decimation of many trees, was inspected critically. The intent was not to create straight roads that would increase vehicular speeds (and then require speed-breakers), but to let the roads wiggle around existing trees and where the roads were multilane, split these up in to smaller lanes and let them snake their way around existing streets. This manoeuvre would help retain many more trees while at the same time reducing the speed of vehicular traffic and increasing the landscape quality of the built environment.

As far as possible, the buildings were placed in spaces between the trees

Locating the Buildings: The location of the individual buildings and their footprints too was often decided based on the location of existing trees and, as far as possible, the buildings were placed in spaces between the trees. In some cases, where the building is located next to a tree with a large canopy, building heights have been restricted, or buildings are stepped back to allow space for the tree-canopies. The urban design scheme is one of buildings which are placed not with a geometric order, but in an organic way around trees. The accompanying drawing on this page shows the intent, as the design evolves.

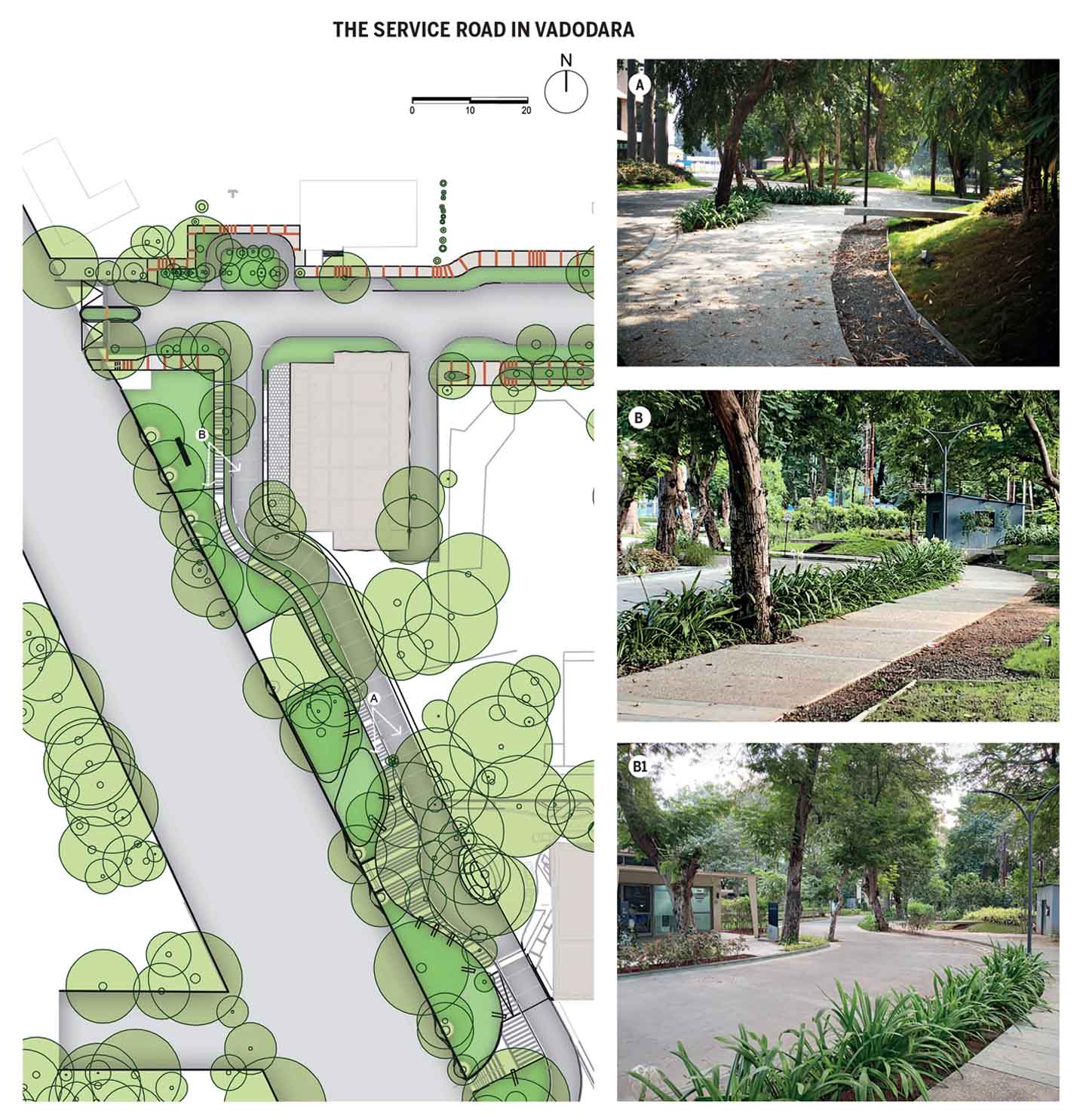

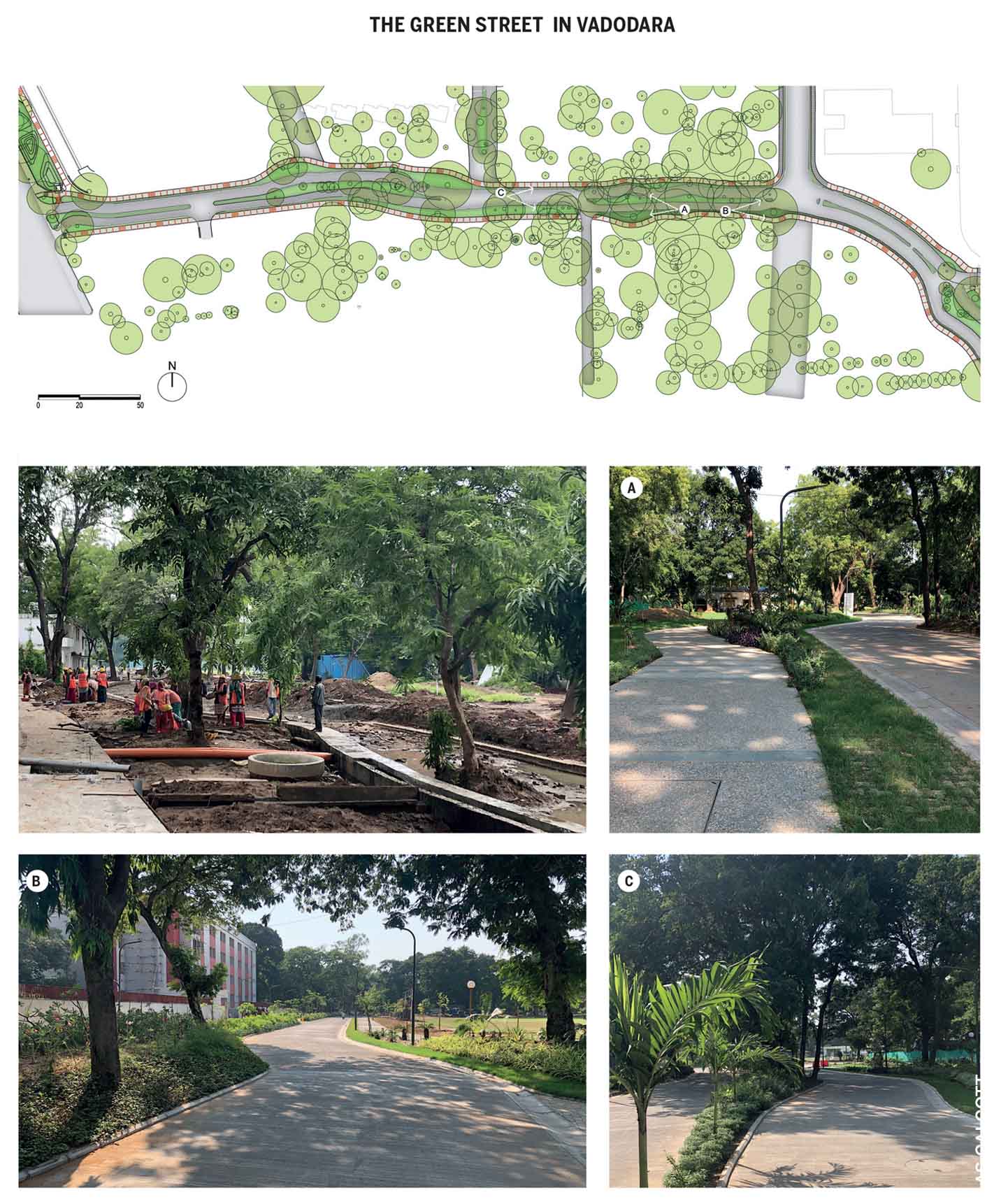

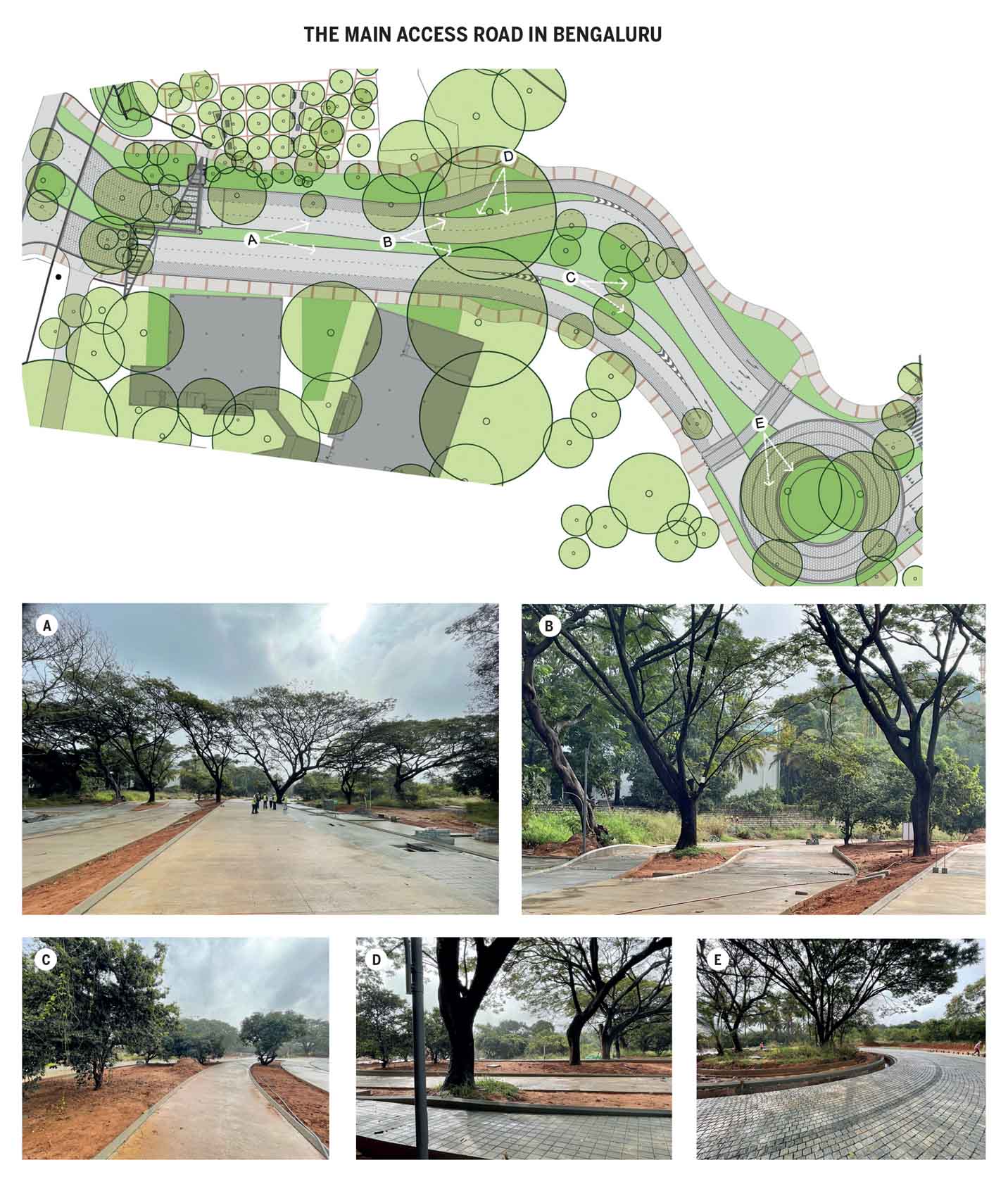

On the following pages the drawings and photos indicate how using these design strategies can help retain many trees on a site.

The illustrations and photos of parts of the site show how remarkable results have been achieved by using these strategies from narrow single-lane roads to broad multilane ones.

|

|

A small road only 250 metres long, giving access to a series of cafes and a large office building. The road snakes past existing trees and ends in a roundabout in front of the office building with a couple of large trees of the Ceiba family in the middle of the roundabout.

|

A major road of nearly 500-metre length had to be created through the site. Since this road not only had to cater to heavier traffic but also had to reserve space for underground services alongside it, we decided to create a median and thereby help accommodate some existing trees there. Locating the pedestrian path at some distance from the vehicular road helped us to retain more trees.

|

As the main vehicular access road from the west side, this road had to be dimensioned to carry heavy vehicular traffic with 2x3 lanes. However, by placing a median between the two directions of traffic and also at places splitting the three lanes, more trees could be retained. The biggest hurdle in this design was a magnificent row of rain-trees nearly 25 metres tall, which lay perpendicular to the access road. For this reason, the access road lanes were split up and laid at different grades, so that the road could cut across the row of trees without having to cut a single tree.

All Photos & Drawings: Lanarch Studio

Comments (0)