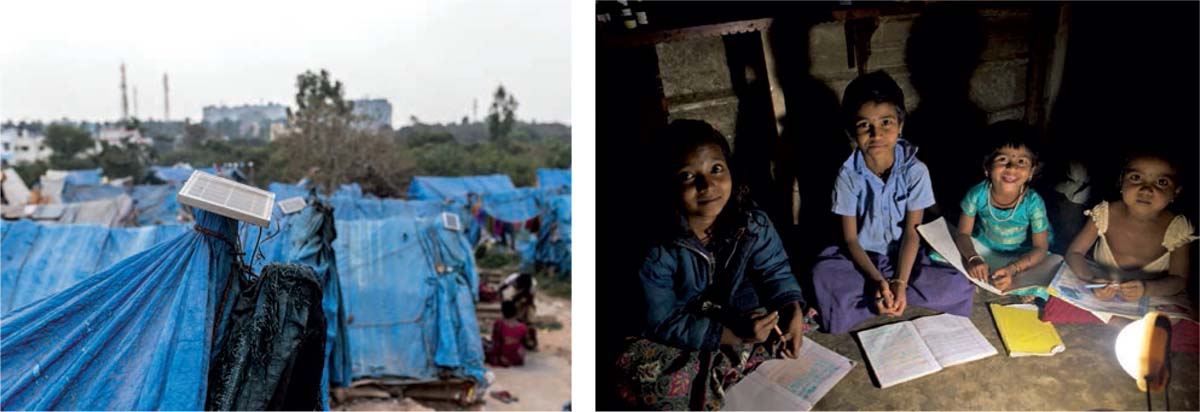

For the last 20 years, Pushpa has lived in the same shanty in a slum in Bengaluru without electrification or sufficient illumination from kerosene lamps. About five years ago, Pushpa attended a financial literacy programme organised by the Parinaam Foundation, where she was also taught to sew. Purchasing her own sewing machine and also two solar lights from a Pollinator that worked with Pollinate Energy, she started a business making and repairing clothes for women in the community. Now, during the day, she works in a canteen and in the night, the solar lights enable her to work on her tailoring business while her children use the lights to study. By saving about Rs 200 per week on kerosene expenses and making an additional Rs 200 a week from sewing at night, she uses this extra money to pay for her daughter’s after-school tuitions.

Pollinate Energy is a young social business headquartered in Bengaluru that is currently focused on giving India’s urban poor access to basic, sustainable products that better their lives. Burning kerosene lamps in the poorly ventilated shanties is extremely toxic, with adverse effects on health besides large amounts of CO2 emissions and poor light quality. The use of high-quality solar lights changes this. Pollinate Energy sells solar lights to slum dwellers who have no access to electricity and so use kerosene. They sell through ‘Pollinators’: locals drawn from low income, disadvantaged backgrounds, thereby offering a dual benefit - a source of income to the Pollinator and a better source of light to the community.

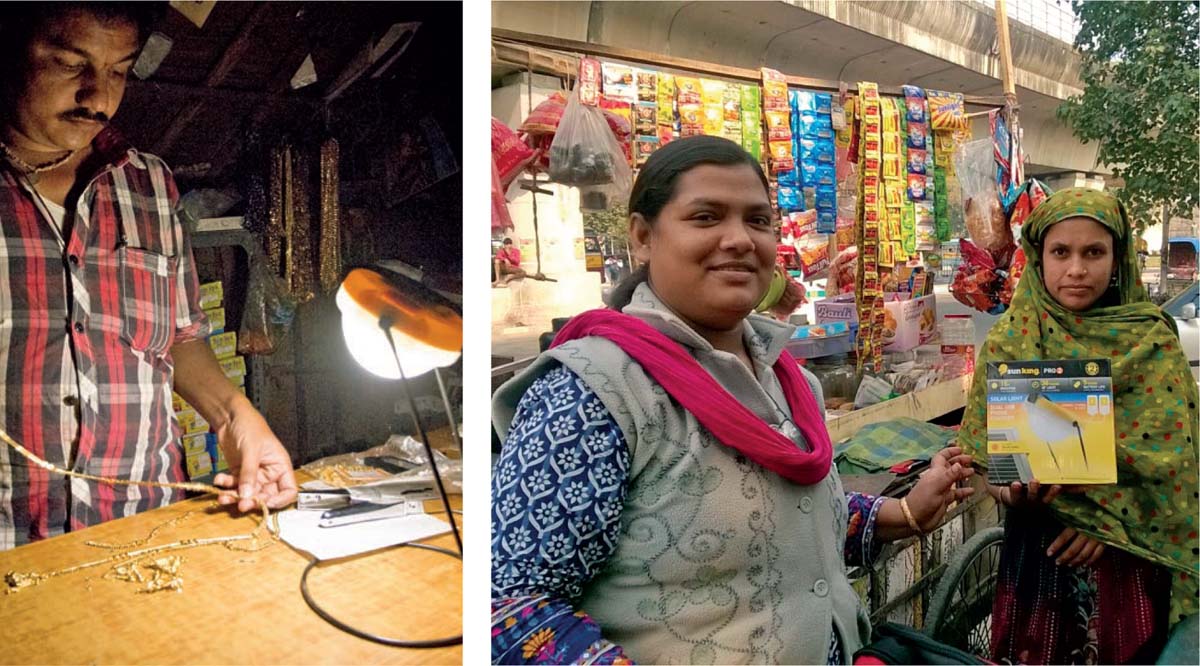

Some of the Pollinators come from challenging backgrounds, but are keen learners and independent workers. Soma, a Pollinator in Kolkata, went from being married at age 16, to becoming a widow a few years later. Now, at 29, she’s a small businesswoman with an 11-year-old son and supports her widowed mother. Her son now helps her sell lights in his spare time; his school wants to buy a light from him too.

Right: Soma selling a light to another businesswoman in Kolkata

Pollinate Energy was started by a group of six Australians in 2012. It was, in essence, co-founder Katerina Kimmorley’s thesis project in Environmental Economics and Climate Change, coming to life. Her husband, Jamie Chivers and his colleague Monique Alfris, also co-founders, were then working with an NGO in Bengaluru involved with educating local children living in slums. When they discovered that the kids were returning home to darkness, they formed some ideas as to how they could improve the lives of these communities.

This then became the subject of Katerina’s thesis. “If we can provide sustainable energy solutions across the world and sustainable energy products to people at the bottom of the pyramid everywhere, that is a world I would like to live in. We basically decided that if we wanted to solve this huge problem, it had to be a business solution. You just can’t give away 400 million lights,” says Katerina.

The three other co-founders, Emma Colenbrander, Alexie Seller and Ben Merven, later joined the team.

Initially, the co-founders were not looking to form a new company. Emma, co-founder and Chief Sales Officer, explained that they were looking to work with existing organisations to take their products into the slums. But there was plenty of resistance to this idea, as slum dwellers were perceived to be too poor to have the capacity to repay loans. They were also told that going into the slums wasn’t very safe. “But we proved everyone wrong,” she said. “These people are very trustworthy and are capable of purchasing these products, if provided with a payment plan.” The organisation, now headquartered in Bengaluru, has also expanded to Hyderabad and Kolkata.

Setting up was a legal nightmare. Unable to speak the local language and looking for preliminary funding made things tough. Pollinate Energy runs a fellowship programme, which was a significant part of their funding, at first. It brings together people from all over the world and exposes them to the work, involving them with mapping new regions for Pollinators, collecting customer data through interviews, testing and trialing new products in communities, and other work integral to the running of the organisation.

Right: Children studying in a shanty

HOW POLLINATE ENERGY WORKS

An initial model of having a shop cart that would be set up at local markets was not viable. They realised they had to go to their customers, rather than expect their customers to come to them. This is where the idea of ‘Pollinators’ came in: locals who would sell the products in the slums.

Pollinate Energy HQ finds the most affordable products that are made available to the Pollinators to sell to slum dwellers. The Pollinators sometimes seek the help of a ‘Worker Bee’: a member of the community the Pollinator serves, who helps the Pollinator generate trust and, in turn, sales within the community. They earn a commission for all sales they assist with. The customers, who are the end users, typically have no bank accounts and take no loans. The solar lights cost them roughly Rs 2500 and can be paid for with a 5-week plan and lasts them 5 years. These work out to be more economical than a kerosene lamp, which would cost about Rs 3640 a year with a recurring cost each year.

The Pollinators are key to the organization and come from economically weaker sections of society. They range between the ages of 19 and 47, with varied educational qualifications: some have college degrees, while others are school dropouts.

Pollinators get stock on consignment and are franchisees of the company. Their success depends on the trust they can build with the slum inhabitants and how hard they work. With flexible work hours, they can pursue other jobs in their free time or attend to their families. Their work empowers them with skills for selling, IT and customer relationship management. The company’s staff trained the first few Pollinators, but now, the Pollinators themselves train new Pollinators. They all use smart phones with a sales force cloud management system to track their sales.

Because slum dwellers are in illegal, vulnerable situations, they are very suspicious of outsiders and fear that they might be exploited or evicted.

So, when Pollinators begin working with them, they face two challenges: educating the people about sustainable products and gaining their trust.

A Pollinator first goes door-to-door to find a family they can talk to and once a slum dweller shows interest, many other people circle around, out of curiosity. The Pollinators then display a demo light, show how it works and use it to educate them about sustainable energy. Arjun Bolangdy, Head of Operations at Pollinate Energy, explained that the key is to convince one person to buy it: that person usually becomes the Worker Bee. “There is consumerism after one person buys it,” he says.

The Pollinator installs the light and allows the potential customer to use it for a week, after paying Rs. 500. If the family is not satisfied with the product, they can return it and get their money back. Almost always, the family keeps the light and other families quickly follow suit.

Krishna and Amreen are two of the most successful Pollinators in Bengaluru. Krishna used to be an artist, painting boards and hoardings. With the flexibility of being a Pollinator, he now does painting jobs in his free time and teaches ‘Michael Jackson’ and ‘Bollywood’ dance.

He has been a Pollinator for two years, serves 18 slum communities and his customers refer to him fondly as ‘Solar Man’. When asked how his experience has been, he says, “My heart is full of happiness!” He is very proud of what he does and that he is able to help people in need, while earning a livelihood at the same time.

Amreen has been a Pollinator for over two years now. Married, with two school-going children, she looks after her family and works in her spare time. Her husband and kids are very supportive and often pick her up from the bus stand when she returns late. When asked whether she faces any challenges being a woman and working with slum communities, she said she hadn’t had any bad experiences so far and that all her customers greatly respect her and refer to her as ‘Light Woman’. She describes her experience as ‘superb’.

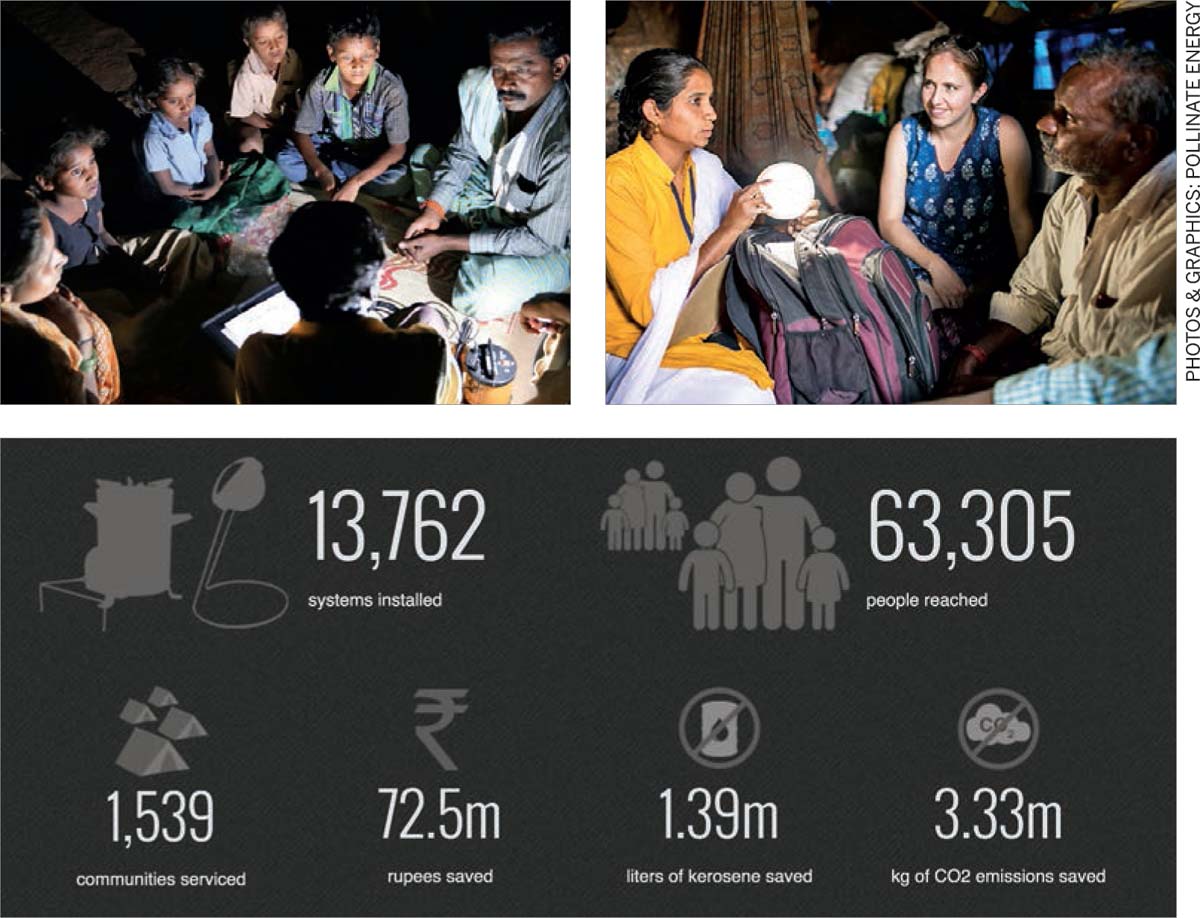

Pollinate Energy, along with their Pollinators, have affected 1539 communities, conserved 1.39 million litres of kerosene and saved Rs. 72.5 million. They were one of the winners of the United Nations Momentum for Change Awards - Lighthouse Activity in 2013. Katerina and Manjunath, the organisation’s first Pollinator, received the award at the UN’s Climate Change Conference in Warsaw, Poland. They have begun selling water filters to further improve the health of their customers and have also started selling mobile phones. They’re testing a new product now: solar fans. By 2020, they want to be in 20 cities and another country.

For more information, visit www.pollinateenergy.org, or contact Arjun Bolangdy, Head of Operations at arjun.b@pollinateenergy.org

Comments (0)