“We live in a moment of transit where space and time cross to produce complex figures of difference and identity, past and present, inside and outside, inclusion and exclusion.” – Homi K. Bhabha

Triggered by the economic reforms of 1991, India has witnessed a continuously accelerating wave of development. This, in turn, has catalysed a radical transformation of the Indian urban landscape. In its relentless pursuit of globalisation, highways, flyovers, skyscrapers, shopping malls and gated apartments now dominate the Indian city. However, in everyday life, there is quite a different reality than the generic images you see of the prescription global city. Social practices, deeply rooted in traditions, are not disposed of as easily as the physical fabric of the city. Social practices inter-punctuate the daily life of the city. So, while the built environment of the city is rapidly and radically transforming, normal life continues to move between adaptation and conservation.

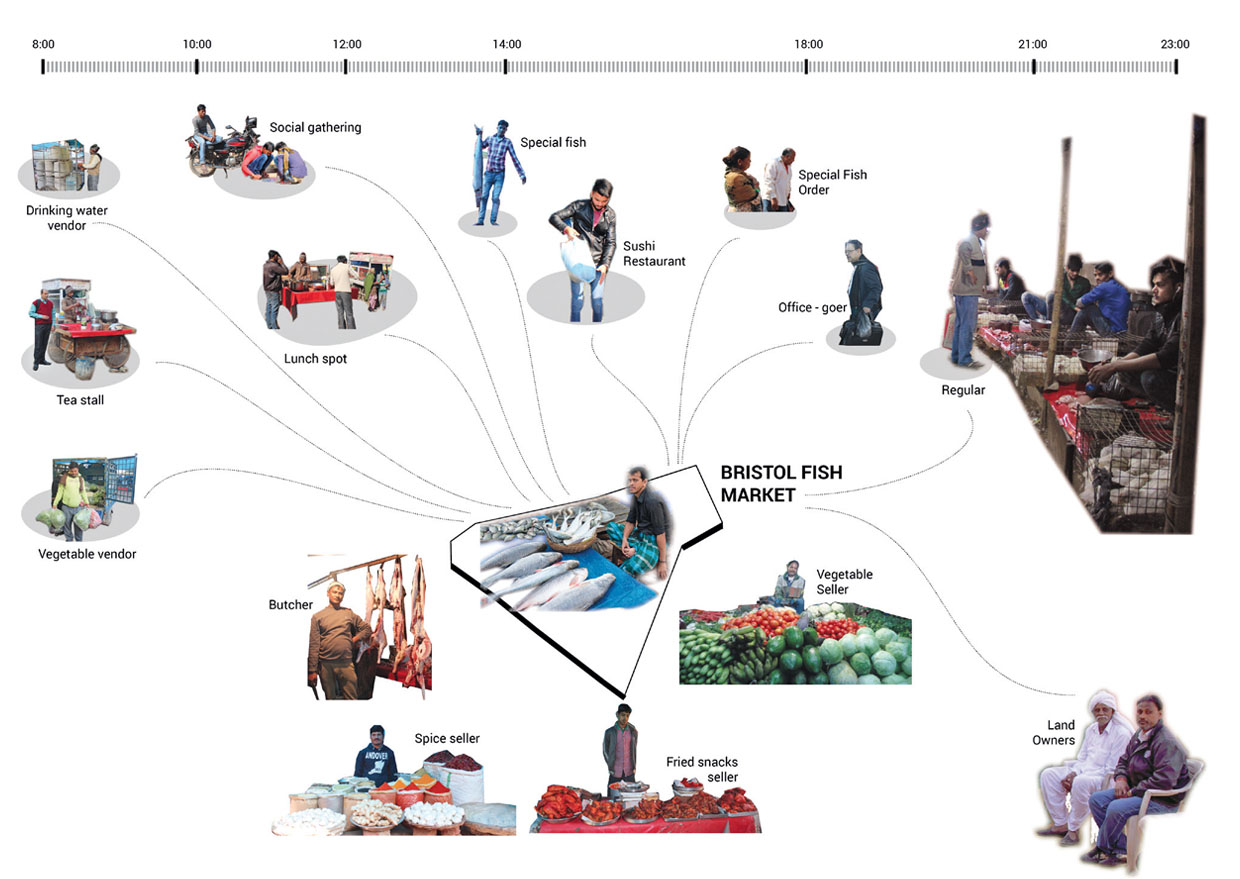

The Bristol Fish Market facilitates various social interactions and becomes a site of entanglement

All this is obvious in cities like Gurugram, which is a leading industrial and financial hub of India. Even physically, the city is caught in this dichotomy. The explosive development of the modern city goes hand-in-hand with remnant rural villages over which the city grew. Hence, Gurugram’s urbanity in the making already contains different worlds within it wherein different aspects of routine life interact and intertwine. This interaction is an essential aspect of the current urbanism of Gurugram. What follows is an attempt to unravel this intimate entanglement that transpires in the making of Gurugram: the enmeshed overlapping of urban lives.

Theatrics at the Bristol Fish Market

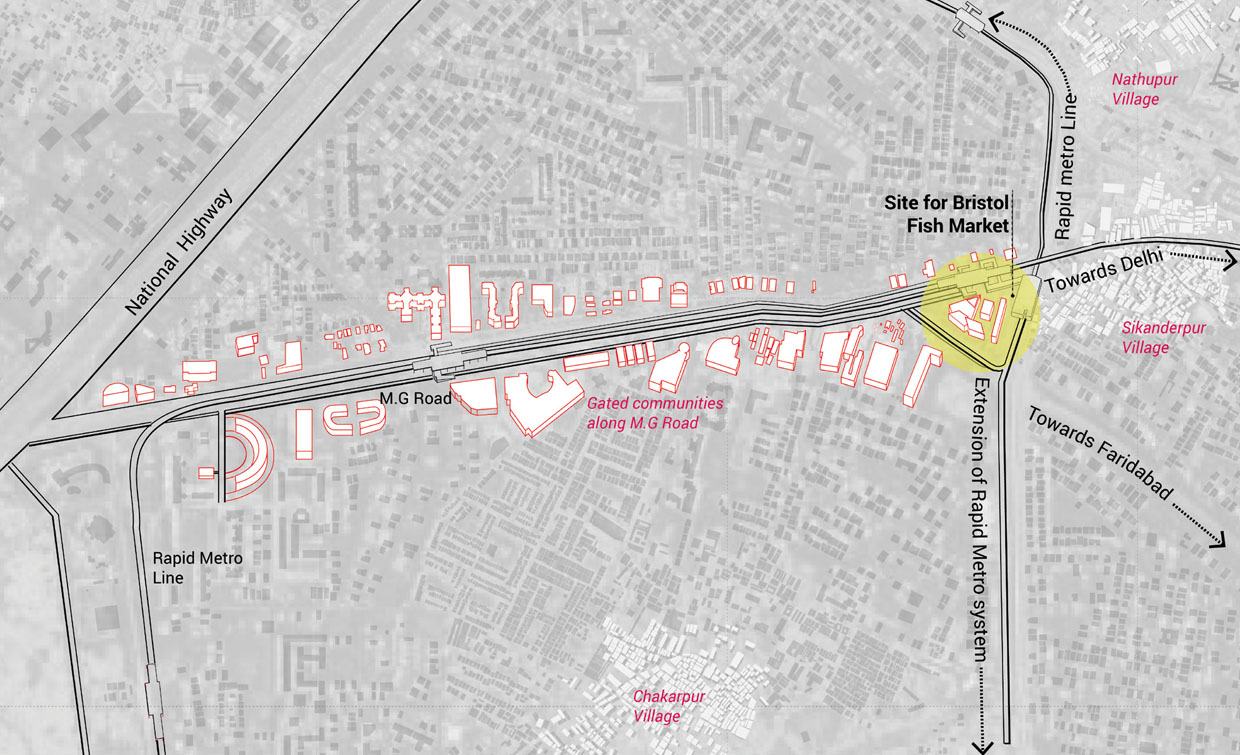

In this perspective, marketplaces are interesting spaces. Indian bazaars are already, by definition, pluralistic sites of exchange where different local identities come together. Bazaars almost always have particular locational assets and hold a specific place in the spatial configuration of the city. As opposed to shopping malls, which are enclosures with a fixed spatial organisation, marketplaces are extremely informal with strong relations to the city. In the same way, Gurugram’s Bristol Fish Market emerged from the inconsistencies in the city’s formal planning. It is an in-between space, a leftover splinter area, cut off by infrastructure, but still accessible. Hence, it generates a perfect setting for an informal market: off the grid yet central. It inevitably becomes the place where different social lives entangle, different urban modes, new and old, fast and slow, come together.

Located next to the Sikanderpur Metro Station, one must either take public transport or the auto rickshaw to access the area. Hence, the space is easily missed. It is supposedly a blind spot, a manufactured error: a narrow rarely used strip tucked amidst private buildings, state roads and the metro. Without strong formal claims by developers (because it is cut off), or from the management of public infrastructure, the site (still owned by the original village community) has been taken over by an informal market.

It generates rent without investment and provides opportunities for income generation, which are offered in the planned formal city-in-the-making. The eclectic nature of the Bristol Market directly brings to mind the indigenous ‘mandi’: a temporary market with the characteristics of a village setting that appears in the morning and disappears by the end of the day. It is easy to perceive it as such, something that comes and goes and therefore does not matter (in terms of fitting formally, obeying formal planning rules, etc.).

Social intertwining: Space as a stage

Bristol Fish Market, as all markets of course, is a place for coming and going. Day after day, a bustling theatre of urban life unfolds: people arriving and leaving, supplying and displaying of fish, greetings and nods, whirling around, examining and choosing fish, negotiating and finalising prices, exchanging goods for money, wrapping up, chit chat, gestures and the like. The built environment stages and frames all this. In the same way that the staging makes certain actions and interactions possible or impossible within a theatre play, the physical environment accommodates and frames social transformations.

Bristol Fish Market is no different: it facilitates various social interactions, forging relationships amongst various actors and becomes a site of entanglement, becoming an open invitation for activities that do not fit the regulated spaces of the planned city.

Synergy in the spatial constellation

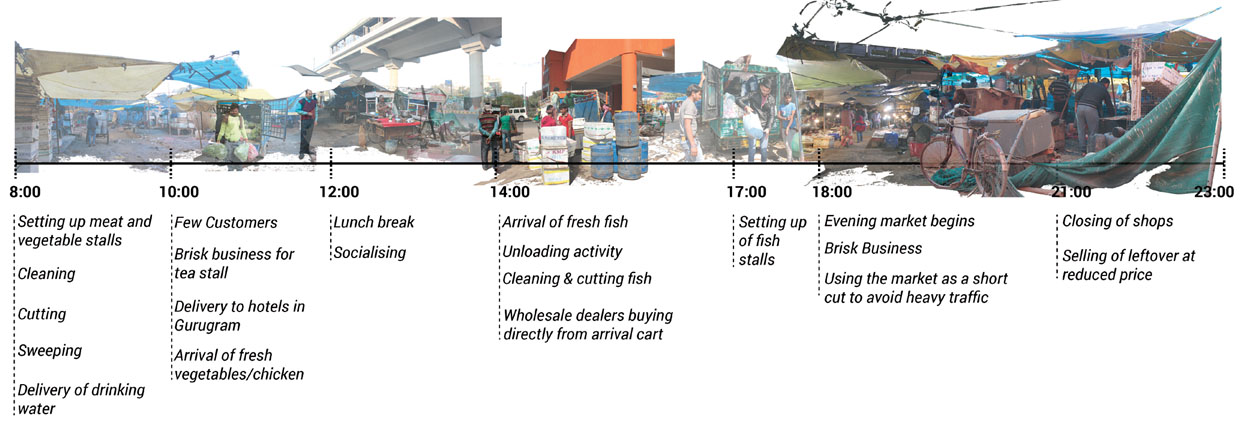

The different actors involved in various scenes of the space occupy different time zones. Looking at the daily life of the marketplace, an interesting schematic can be generated where the space comes to life at specific times. At other times, it seems to be preparing itself to absorb the chaos and the messiness that is so often associated with a fish market. As the different forms of ordinary life unfold in the market, it brings out individual tactics of space appropriation, transforming the site within the city’s formal planning. In the process, flexibility of space is revealed.

Gurugram’s hybrid sites

The generic supermarkets of the global city-in-the-making do not supply fresh fish. The Bristol marketplace fills this gap without too much pomp, organising itself with the original village community, whose land the market is installed upon. The site acts as a hybrid zone bringing together urban villagers as renters, fish sellers as tenants and fish lovers mainly from nearby gated complexes, as well as professional sushi restaurants. There is retail, wholesale and everything in-between associated with fish: vegetables, meat and spices. There is water or tea for a break in the activities.

Middle: Setting up the market

Right: Brisk business

Amidst the teeming all this generates, are the different entities of Gurugram: the elite lifestyles of the planned city, the servants of all sorts (drivers, porters, water suppliers, etc.), the transforming roles adopted by the urban villagers and the working class with various degrees of poverty (but all very poor). All contribute to fueling of the in-between sites. A complex ecology instantly emerges, bringing out the interdependencies between people, between goods, as well as people and goods. Sites such as the Bristol Fish Market, in return, fulfil different everyday needs of the city and act as flexible spaces that negotiate and house irregularities of the city: activities that formal planning, let alone the private market, do not provide. Hence, one fuels the other and neither can survive without the other, revealing an inherent truth of emerging cities such as Gurugram making it possible for such in-between sites to exist alongside the dominant image of the city.

The different actors involved in various scenes of the space occupy different time zones

Bristol Fish Market can be seen as a space of negotiation, functioning in a village-like setting where business works by word-of-mouth. Sellers spend a majority of their day on the site and hence, the space functions much more than a site of business. Because the city provides no public space to the blue-collar workers, the space opens up as a site of social interaction, building connections and leisure activities. In that sense, the social aspect of the site adds another dimension to the spatial configuration of Bristol. The existence of these interstitial spaces in the city act as overlapping layers that open up the fixed notions of the city: the aspiration of the city to be a part of the global world. It then reveals the temporal space that breaks up one single image of the city.

Comments (0)