PHOTO: AUTHOR

Cities are places of exchange where different worlds, both natural and man-made, meet, merge or even collide. Although intrinsic to cities, such exchanges often present urban designers, policy and decision makers with challenges. One such test today is social inequity particularly when it is concentrated spatially.

Social inequity is symbolised by the stark disparity in the quality of the living environment. Within cities, it manifests itself as a patchwork of ‘contrasting urban forms’: on one end of the scale are the exclusive-luxury neighbourhoods while on the other impoverished-informal neighbourhoods. Such an urban ‘contrast’ is not just a physical expression of income inequalities, but a representation of more innate social conditions such as patterns of segregation and exclusion, distribution of power and public-participation and, more importantly, the access to and availability of choices and opportunities to gain full benefits of city life.

Urban inequities that limit certain segments of society from fulfilling their basic needs and development potentials, create fractures within the society, leading to social unrest. This in turn threatens the national security and hinders economic growth.

Increasing insecurity and fear among the citizens further shape the sprawling city through the growth of defensive (i.e., high security, gated luxury) neighbourhoods leading to, what the authors van Ham and Clark call a ‘spiral of decline’, which is a combination of both, physical and social problems that reinforce each other. Described as political and policy concern, inequity can also be seen as an important structurally threatening cost to governments including social security, health, education, law and order and housing and environment disbursements.

Urban inequities therefore, not only pose a danger to a nation’s social stability and sustained economic growth but also make growth itself destabilising. Equity in the built environment, today and perhaps even more importantly in the years to come, remains an important facet of ‘just and sustainable’ development especially for rapidly urbanising nations like India whose massive population rise and high migration rates cause concerns about effective and equitable urban service delivery to meet citizens’ basic needs.

Equity has received general recognition and has been a recurring theme in the government’s policies and urban reforms right from the 7th Five Year Plan. Yet, the topic–how it can be tackled within the realm of built environment–has been less adequately addressed. This article attempts to explore the concept of social equity, its constructs and implications within the built environment.

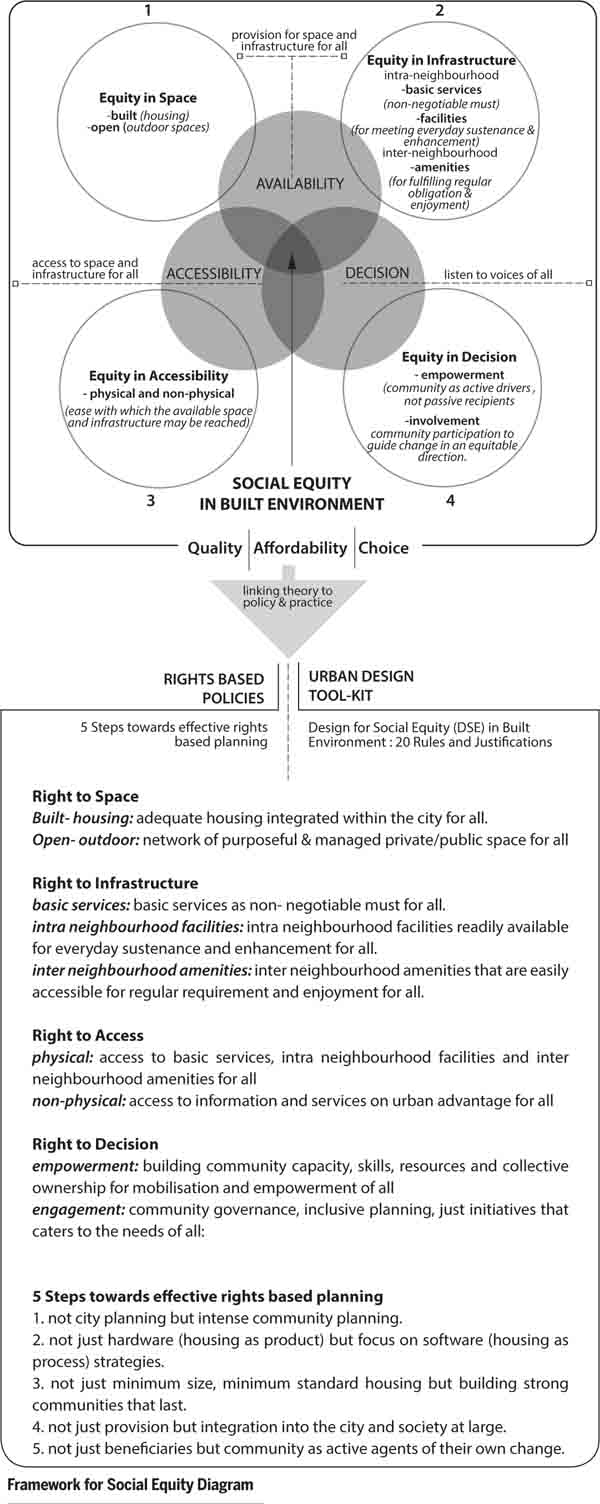

It uses the context of an informal neighbourhood (slum) and affordable housing provisions in India as a laboratory to ask questions like: How can social equity be more effectively integrated in urban development plans, in particular affordable housing? What are the opportunities for action? To this, our understanding is finally translated into a social equity framework focusing on Right to Space, Infrastructure, Access and Decisions in the built environment. Once we have the answers, we will understand the social equity framework.

What is social equity and what are its constructs?

The concept of equity, strongly associated with the notion of social justice, implies that the basic needs of all the people, to both survive and fulfil their development potentials, should be fulfilled and that economic, environmental and social benefits, damages and costs including participation in governance need not be spread unevenly but be shared with fairness and justice across communities and neighbourhoods within a city.

Within the urban built environment, it suggests a requisite for minimum (preferably an optimum) level or benchmarks for satisfying basic urban needs (spatial, social, economic, environmental and political dimensions) so that everyone can enjoy all the benefits the city has to offer.

Social equity in discourses on sustainable growth and pro-poor policies has received immense recognition. Several authors have identified it as an integral component of the social dimension of sustainability and individuals and organisations have made various attempts to operationalise the concept in practice. Yet the meaning and construct of social equity in the built environment remains vague due to several reasons: 1. The concept lacks an agreed definition 2. It is interpreted variously from different disciplinary backgrounds 3. Its measurement is difficult and 4. It is context dependent.

Although inequitable outcomes and exclusionary processes operate along and interact across several dimensions (economic, political, social, cultural and physical) and work at different levels, equity within the built environment can be seen to have three major constructs:

1. Availability: Provision for space and infrastructure for all

This refers to: a) Equity in space, both built (housing) and open (outdoor spaces) and b) Equity in Infrastructure, intra-neighbourhood basic services (non-negotiable must-haves like cooking gas and electricity, drinking water and sanitation, waste management) and facilities for meeting everyday sustenance and enhancement like medical, banking, educational and open recreational facilities as well as ‘daily domestic dos’ such as food and groceries, fresh vegetables and fruit ‘haats/mandis’ (multiple stalls), laundry and newspaper/tea stalls as well as inter-neighbourhood amenities for fulfilling regular obligations as well as leisure, shopping and restaurants, clubs and sports centres, community centres and places of worship/faith, cultural centres as well as libraries.

2. Accessibility: Access to space and infrastructure for all

This refers to equity in access, both physical and non-physical, actual or perceived. The ease with which the available space and infrastructure i.e., services, facilities and amenities may be reached. (Although essential, the non-physical and perceived access is not considered here)

3. Affectability: Listen to the voices of all

This refers to equity in decision-making through community empowerment and involvement in development and planning processes so as to make both approaches – top-down and bottom- up – effective in design and functioning of built environments.

Further to the above three, Security (tenure), Affordability and Habitability can also be seen as other associated constructs.

How does the built environment affect social equity and what are the challenges India faces?

Design of urban built environments and policy decisions have far-reaching social equity impacts as it can either enable or restrict certain segments of the society from access to resources and opportunities offered by the city. This can influence individual, community and the country’s well-being. Dempsey and her colleagues from the UK have emphasised that equity and inclusion are also critical on the local or neighbourhood scale where they relate to everyday experience of the built environment and play a more important role especially for, but not limited to, ethnic minorities, low-income residents, persons with special needs and the elderly.

Further, my research at IIT Guwahati (2012- 2016) on the influence of the built environment (defined by five urban form components: density, land-use, open spatial-network, urban-blocks and built-components) on six aspects of social sustainability, clearly proves that built environment influences the level of social equity amongst its residents. ‘Availability’ and ‘accessibility’ to basic services and facilities as measures of social equity strongly influences residents’ attachment to a place, which further affects their length of stay in a particular locality or neighbourhood. Length of stay, in turn, has the potential to influence all the other aspects of social sustainability such as residents’ level of social interaction and networks, trust and reciprocity, social participation and the feeling of safety and satisfaction in an area. Locational advantage of people’s place of residence is also perceived important, which includes not only convenient access to local facilities but also availability of choices and access to city-level attractions.

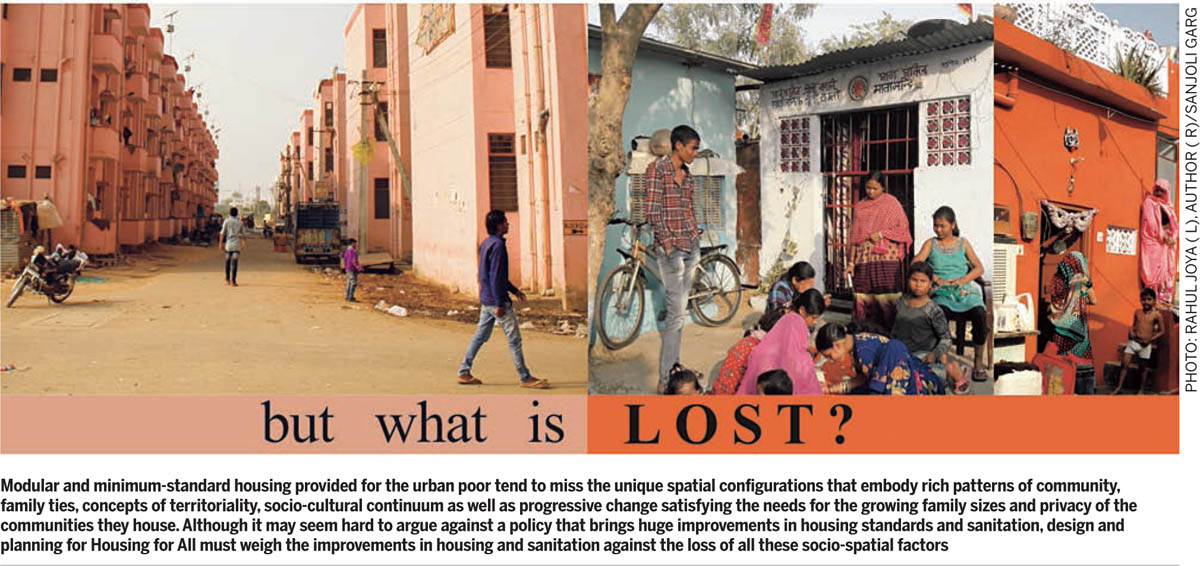

These theoretical investigations brought us in close proximity to the understanding of the concept of social equity, its meaning, construct and the influence of the built environment. However, our understanding concerning the social equity outputs, ‘What does an equitable neighbourhood look like?’ or ‘How do we ensure equitable neighbourhood change?’ is found to be non-existent. As a result of this, the concept currently suffers in India’s development policy and practice, where it either becomes a meaningless label generally added-on to promote the message of other disciplines (such as environmental concerns) or, in some cases, ousted altogether largely on the basis of its intangible and context-dependent nature that causes difficulty in clearly defining and more so, quantifying it. While this indispensable concept is used intuitively in urban development agendas, its implications in the urban built environment, particularly design for urban poor, continues to be fuzzy. Social equity goals are usually not translated into clearly specified objectives and appropriate measures for assessing their achievement in a meaningful, disaggregated manner. Hence, social equity issues are likely to get further reinforced or recreated elsewhere. Housing for the urban poor, therefore, continues to remain the obvious physical manifestation of economic inequity in the form of strikingly distinct neighbourhoods despite several policies and initiatives to reduce the poverty and social inequity in health, education and housing.

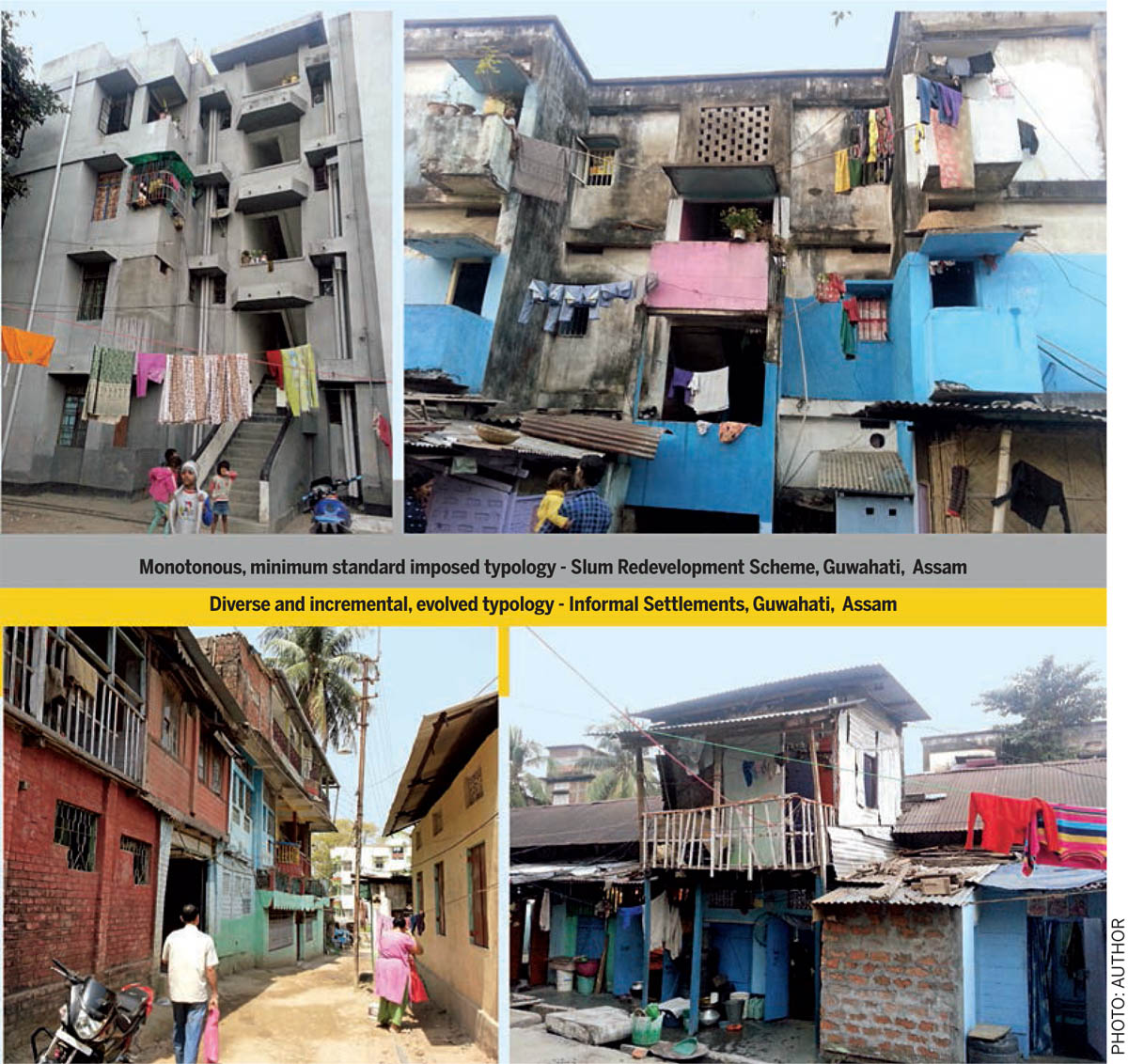

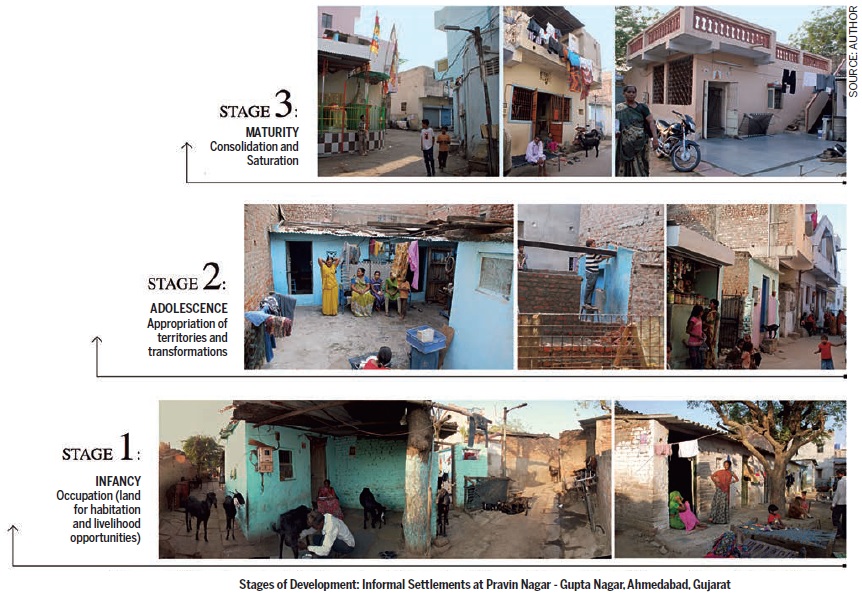

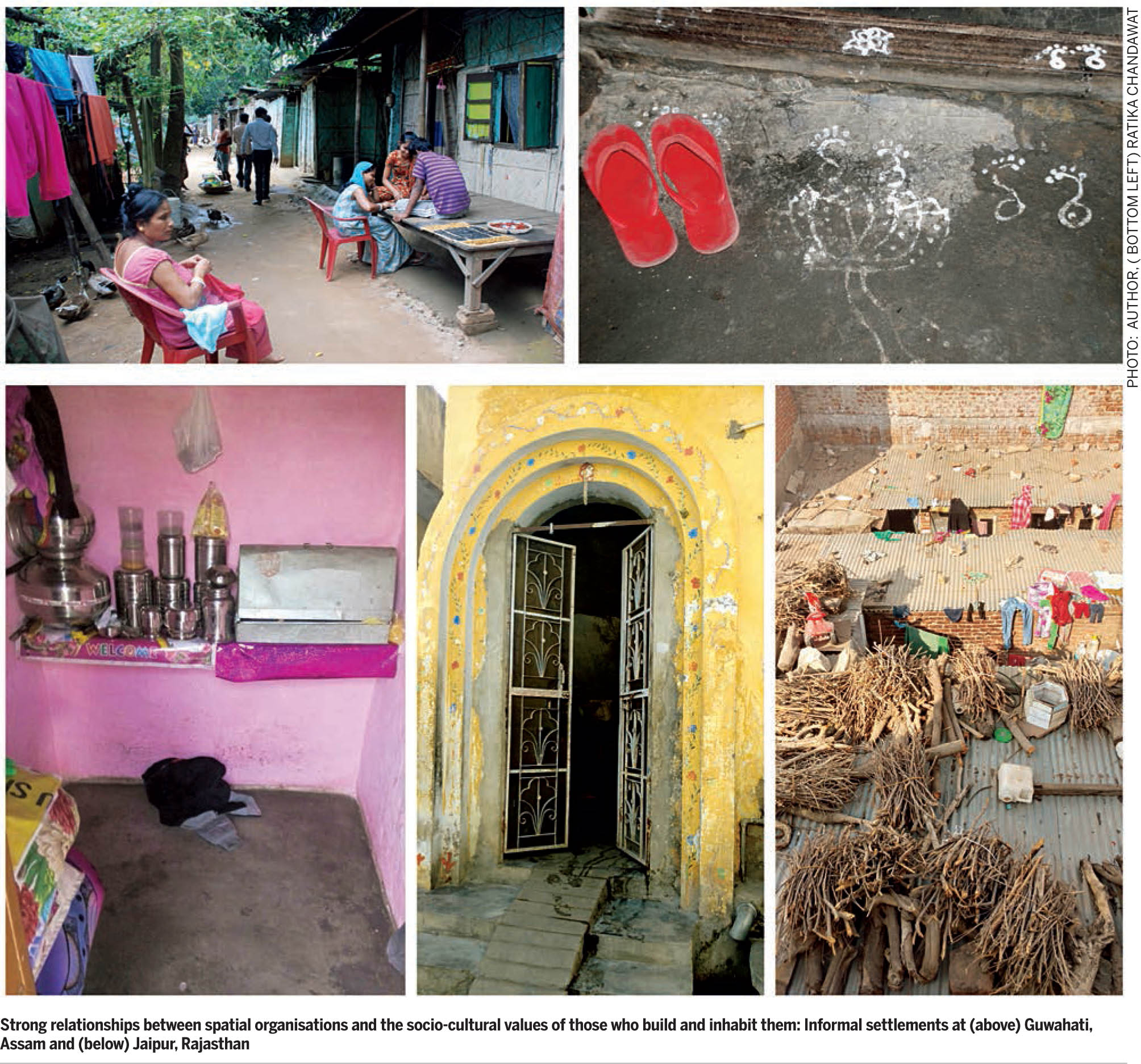

To add to this gap, providing a decent living environment for the urban poor remains a complex undertaking of multifaceted nature, where informal neighbourhood redevelopment has historically meant imposition of new typology of developments (high rise, minimum-size, minimum-standard apartment blocks), that rarely takes into account the economic potential and socio-cultural values of its resident community. The situation is further complicated by lack of finance, issues with respect to access to land and security of tenure, as well as pressures of scaling up to meet the heavy infrastructure and housing demands. Together, these deficiencies allow for only limited success in efficient and equitable built-environment for the urban poor and induce a vicious cycle of poverty as well as slum formation.

As India prepares for the influx of another 350 million people by developing a number of new greenfield cities whilst improving the condition of its existing urban population, there is clearly a pressing need to develop a stronger link between the conceptual/theoretical constructs for social equity and its implications in urban design, policies and practices, particularly in relation to informal neighbourhoods or slums.

How can we link the Social Equity concept to policy and practice and what is the way forward?

Planning and designing for social equity requires imagination. It requires a sound assessment of the ground issues allowing ‘just and sustainable’ growth of a city within the bound constraints of its demographic, physical, socio-economic, jurisdictional and financial aspects. An exploratory article like this calls upon further research based on a comprehensive social equity index or benchmark, which can effectively guide India’s future growth and design of new cities particularly the ‘smart’ ones. Such evidence-based policy and design guidance can help designers, planners and decision makers in their efforts towards reducing the divide between smart growth and social justice. Emphasis on equitable processes and outcomes can foster real change that benefits local communities over time.

A framework for social equity, with two key components: planning policies and a design tool-kit, can be seen as the first attempt to initiate thinking and discourses on linking the indispensable but hard-to-materialise concept of social equity to urban design policies and practices. Responsive to the present socio-spatial context, such a framework may evolve or change in tandem with transformations in the society and its relevance may vary with time and context thus requiring regular evaluation of its implementation. A ‘Social Equity Design Tool-Kit’ is beyond the scope of this article.

However, five steps towards effective rights- based planning can certainly be discussed here (See the Framework for Social Equity Diagram).

The present contrasting urban forms and socio-spatial shifts threaten the country’s commitment towards inclusive, sustainable urban development by 2030 and its efforts towards becoming a smart, global player. Amidst the rapid expansion of India’s urban areas alongside intense growth of informal neighbourhoods (slums), a framework for social equity in built environment that not only informs the urban practices through micro-level interventions but, also becomes integral to development policies, can be seen as essential to make the country’s urban growth and transition more just and sustainable.

This article advocates urgent and sincere efforts to first contain and then reduce the rising levels of extreme social inequity in the built environment, to make the dream of ‘acchhe din’ (good days) for the 300 million Indians – nearly a quarter of whose population live in informal neighbourhoods in extreme poverty and vulnerability – a reality.

Comments (0)