|  |

PHOTOGRAPHS: IMAGEBANK/CORBIS, MEETESH TANEJA | |

Introduction & Historical context

Hyderabad is more than 500 years old. The original settlement established under the Kakatiya Dynasty underwent change of control from the Qutb Shahis who developed and consolidated the famed Golconda Fort to the Mughals whose Viceroys ruled under the title of Nizam.

From the earliest engineering marvels, pre- dating the modern city of Hyderabad, like the Hussain Sagar Lake (1562) that provides water to the city to the landmark Charminar (1591), symbolizing the end of the dreaded plague and the creation of a new city, Hyderabad is undoubtedly a city of landmarks.

Through the centuries, Hyderabad grew as a prominent center for trade, art and culture. By the end of the 18th century, Hyderabad State had come under subsidiary alliance when the British added its cantonments creating a unique character with large green spaces and colonial-style bungalows that influenced the architecture and city shape of Hyderabad tremendously.

After 1948 Hyderabad State became part of the Indian Union and Hyderabad city was retained as the capital when the state of Andhra Pradesh was carved out.

Post-Independence and between the 1950s and 1990s the city saw a steady growth of public sector undertakings, central government agencies and armed forces establishments. During this period, Hyderabad was a laid back, relaxed town still offering the qualities of a big city until the Indian economy was liberalized and brought about the IT boom.

By the end of the 20th century, Hyderabad was again positioned to take center stage as the global economy energized the citizens to lay the foundation of the new growth surge.

Transformation of Hyderabad into a Metropolitan Region

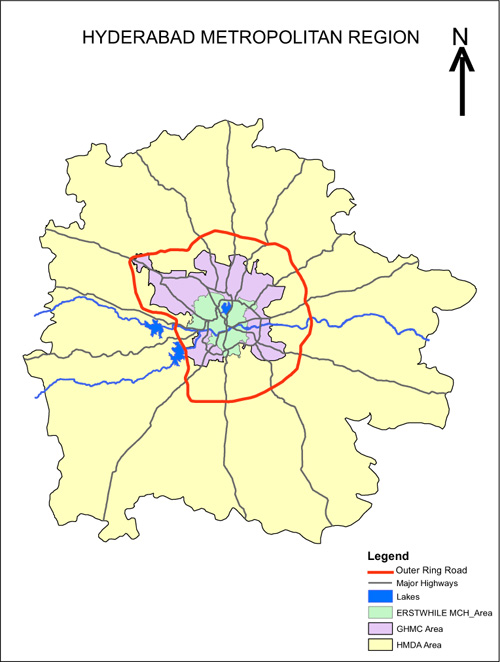

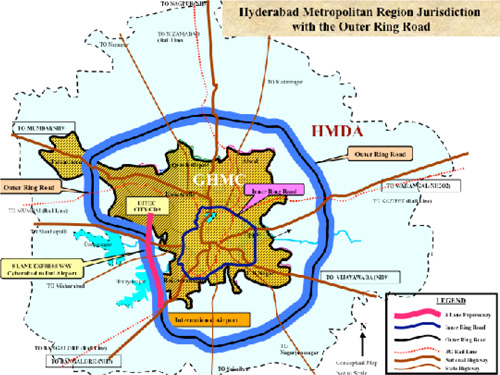

The spatial pattern of Hyderabad is a radially-outward urban area. The core city area (erstwhile Municipal Corporation of Hyderabad, MCH) of around 172 sq kms with a total population of around 4.1 Million (2011) was merged with the surrounding municipalities into one single entity called the GHMC (Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation) admeasuring around 650 sq kms. The radiating roads (33 arms including national highways and state highways) connect the core of the city with the outer development areas and with the Outer Ring Road (ORR) that encircles the city.

PHOTOGRAPHS: HYDERABAD METROPOLITAN DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY (HDMA)

Most of this GHMC is urbanized and the peripheries on the inside are witnessing green field development as well as infilling at a rapid rate.

This spatial pattern offers the opportunity for planners and implementers to develop a hub-and-spoke model of development, which works on the concepts of multiple nuclei, nodal development and will channelize more energy and investment into the infrastructure and implementation plans.

Keeping in view the rapid urbanization and spatial impact of this growth potential in the future, the Government of Andhra Pradesh created the Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority (HMDA) formed by an Act of the Andhra Pradesh Legislature in the year 2008, with an area of around 7,200 sq km under its purview. Keeping aside the unique case of the National Capital Region (NCR) Delhi, this is the second largest urban development area of its kind in India, after the Bangalore Metropolitan Region Development Area (8,005 sq km) and has an estimated population of around 10 million already (2011).

•Metropolitan governance now becomes one of the foremost challenges policy makers face in urban India today.

•Measures to regulate the fast-growing urban sprawl and crumbling infrastructure of cities need to be tackled now with more innovation, use of appropriate technology and much more increased participation from the citizens of India.

The growth story: Public Private Partnerships (PPP)

Spurred by private sector entrepreneurs and supported by dynamic political leadership under its erstwhile Chief Minister Nara Chandrababu Naidu, the city harnessed the tremendous demand for IT and IT-related services in time to ride the global IT wave.

Policy reform along with market economics led to the inflow of huge investments and fresh population who wanted to make Hyderabad their home as it offered good employment opportunities and a comfortable and affordable urban lifestyle.

Successive governments took up the challenge and undertook bold policy initiatives, planning and implementing critical projects related to urban development and infrastructure upgradation.

A large part of this surge has been through public private partnerships (PPP). The Government of Andhra Pradesh entered into a PPP with leading development and construction companies to create Cyberabad, the new IT precinct of Hyderabad. This area, along with the new Financial District at Gachibowli, now provides more than a million direct and indirect jobs.

Some of the other notable PPP projects that have become global icons are the Hyderabad International Airport, which is the first airport in Asia to be awarded the LEED NC, Silver Rating by US Green Building Council and the Hyderabad International Convention Centre (HICC), which is a purpose-built and state-of-the-art convention facility, the first of its kind in South Asia making it a sought after international destination.

Increased role of Public Participation in the Development Process

In 2010, the Government of Andhra Pradesh revised and notified the Master Plan for the Core City area (172 sq kms) after a gap of 35 years. The process was supported by rapid assessment of the existing situation, use and leverage of appropriate technology and emphasis on public participation. The overall objective to put forward a plan for better quality of urban living, as well as the health and wellbeing of the citizens was central to this concept.

PHOTOGRAPHS: IMAGEBANK/CORBIS & HARSHA Vadlamani

For the first time extensive and widespread public consultations and stakeholder workshops were undertaken with various government departments and civic agencies, municipal councilors, civil society groups and NGOs. This set a good precedent.

Emergence of Resident Welfare Associations

On the public participation front Hyderabad has witnessed the growth of Resident Welfare Associations (RWAs), which is a result of the citizens’ response to urban management at the local level. Numerous RWAs have now come under the common umbrella organization of the United Federation of Resident Welfare Associations (U-FERWAS) and have numerous activities reaching scores of citizens and various government officials updating them about activities at the locality level regarding improvement of basic services.

So much so that the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC) now formally interacts with the civil society groups and works under a unique semi-formal partnership with them.

Hussain Sagar Catchment Area Improvement Project

One of the important projects being implemented is the JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency) assisted HCIP Project (Hussain Sagar Catchment Area Improvement Project).

To ensure more public participation the HMDA facilitated ‘The Forum for a Clean Hussain Sagar’, an open platform for all concerned citizens to share, discuss, ideate, initiate and execute programmes that will help clean Hussain Sagar Lake. The main objectives of this effort are to establish a people’s movement to clean and protect the lake and, ultimately, to change people’s domestic and public sanitation habits.

Transportation issues in the city and new experiments in the Indian context

Bicycle tracks

As part of a combined initiative, various government organizations are coordinating and developing a bicycle movement plan for Hyderabad.

The Andhra Pradesh Industrial Infrastructure Corporation (APIIC) has built a bicycle track in the IT precinct of Cyberabad and actively promotes cycle rallies and walk to work concepts. The Hyderabad Metropolitan Development Authority (HMDA) is undertaking a Comprehensive Transportation Study (CTS) to identify four major stretches for implementation of Non-Motorized Transport (NMT) having continuous sidewalks (footpaths) and bicycle tracks. The Hyderabad bicycling club is one of the fastest growing associations of its kind in the world and undertakes activities at regular intervals.

Transit Oriented Development

The 162-kilometer Outer Ring Road (ORR) encircles and encompasses the existing urban area and will be seamlessly connected to the core city by radial roads. From the public transportation point of view, the highlights of ORR include providing a linkage to the proposed Mass Rapid Transit System (MRTS) and Existing Multi-Modal Transport System (MMTS) and bus system and having an exclusive Right of Way reserved for a future rail line for mass transportation.

With the intent to provide a MRTS within the urbanized area of Hyderabad, the government of Andhra Pradesh has embarked upon the Hyderabad Metro Rail Project.

The US $ 2.5 billion project is now the largest metro rail project of its kind in the PPP format to be taken up anywhere in the world. The project covering 72 kms along with 66 stations is expected to transport around 1.5 million within a few years of being commissioned and is under brisk implementation by Larsen & Toubro, one of the largest and most respected construction companies in India. Efforts are being made to integrate the Metro Rail with other public transport systems such as the rail based MMTS and bus-based systems.

Path Breaking Initiatives taken by the Government of Andhra Pradesh

Removal of FSI Restriction: Liberalized development regulations

In a paradigm-changing leap, the Government of Andhra Pradesh simplified the building byelaws of Hyderabad in 2006 by identifying the fact that “earlier building stipulations were cumbersome with too many parameters for regulating and controlling development and building activities.”

A new set of rules with minimal parameters and in sync with the principles of encouragement, facilitation and regulation created a liberalized regulatory framework for all development activities. A key highlight was the removal of the concept of FSI as a restricting mechanism but with checks and balances.

E-governance Initiatives

The Government of Andhra Pradesh launched the Mee-Seva project in 2011 (an advancement from the earlier E-Seva), a faster web based, transparent and secured citizen-centric service facility to provide convenient access to the citizens without any need for them to go to multiple government offices for getting their work done. More than 100 new G2C services pertaining to revenue, registration, municipal departments, police, civil supplies, school education and RTA have been added by providing a very friendly interface to the citizens transacting their activities and saving millions of man hours every year.

Solid Waste Management

GHMC has been recognized and awarded for its improvement in Solid Waste Management under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission supported by the Government of India. The Offsite Real Time Monitoring system (OSRTS) launched by GHMC leverages information and communication technologies to streamline and monitor progress of waste management. The GPRS technology allows cell phones to track various activities such as attendance, working hours, clearance of dumper bins and street lighting. The information transferred to the central server is available online to everyone, including citizens. From the management point of view, the key highlight was that 1005 dustbins and 2384 workers are being monitored with mobile technology. This has led to include increased transparency and accountability, as the information is available for anyone to verify without the scope of public officials manipulating the data.

Conclusions

It is said that Quli Qutb Shah (the founder of Modern Hyderabad) sang the following couplet at the city’s inauguration: “Fill up my city with people, my God, just as you have filled the river with fish.”

The prayer seems to be coming true in some sense as even at today’s truly challenging cross roads Hyderabad is teeming with millions and competing with other major cities of India.

The resurgence of Hyderabad has transpired within a span of two decades thanks to proactive government policies and undoubtedly a substantial role being played by the private sector.

What was known to be a historic city with an amenable climate, Paleolithic rock formations, numerous lakes, cantonments and delectable cuisine has become a hub of economic activity.

The influx of lakhs of skilled workers has added a new flavour to the already colourful city. Today, Hyderabad is the sixth largest city in India in terms of population (8 million), and exports around 15% of the total IT/ITES exports from India and has a GDP of around 11 billion USD.

Despite this huge transformation it offers a composite economic, physical, cultural and affordable urban environment to its citizens.

Comments (0)