The entire network of Indian Railways is undergoing a transformation as a part of a station modernisation programme by the Indian government. The approach to conserve the heritage of Indian Railways when the entire network and its component parts are undergoing planned upgradation is the point of enquiry in this article. Since its inception in the 1850s, this is the first organised upgradation to accommodate increased passenger footfall, diversify function, enhance multi-modal integration and direct growth over a 40-year period.

Till date, upgradation focused on operations, infrastructure and amenities within the station, with minimum interaction with the context. The approach now is comprehensive and focuses not only on improvements to operations, capacity, services and user-comfort but also in reintegrating stations within their context. The object is to regain the dominance of the railways as a self-sustaining transport facility and a major economic driver.

Therefore, changes may range from drastic to minor, may be irreversible and sometimes of shock value. The challenge here is to conserve railway heritage through an approach that harmonises the past with the future. Achieving this will require a departure from existing preservation and control bias to one that is adaptive and defines how conservation enables growth. Such an approach is pragmatic and the need of the hour if the potential of industrial heritage is to be harnessed.

There are two primary shortcomings in the existing framework which necessitate separate codes for development in and around railway heritage. Firstly, the existing norms do not facilitate the incremental changes that are normal for a railway station. Secondly, its binary bias excludes unprotected heritage from any form of preservation or acknowledgement.

This is a cause for concern for railway heritage because when the value of 400 randomly selected unprotected stations were compared to 24 protected ones, more than 70% were found of equal value, worthy of protection. Should the same attributes be extrapolated to 8,000 stations, the number that deserves protection would increase exponentially. But, is legal protection enough? Is it the only way to take heritage forward? Can compatible and adaptive use be a solution? This article explores the latter possibility.

Globally, there is no consensus on how to use and visualise the future of heritage. Although adaptive (re)use has been a popular approach, a recent European Union report assessing adaptive reuse practices concluded that it is no silver-bullet. It is a case and context sensitive practice. Using lessons from one project to visualise another, is problematic. However, it conclusively points out that to retain the essence and value of heritage, at least 60% of the original function (or its closest form), should continue. Which means, functionality is important and use is a thread of continuity and retaining both, conveys their value and the importance of physical space. Also, when functional, heritage makes the past palpable, our identities real and instils a sense of responsibility.

The Indian Railways is an international and shared heritage. According to the Railway charter, its heritage includes historic and preserved railways, tourist railways, tramways and railway museums, historic fixed and rolling stock, fixed and moving structures and equipment currently in use or otherwise, archival material, drawings, photographs, publicity material, (films, posters, pamphlets) estimates, journals, designs and prototype models, industries, housing, commercial and administrative establishments and all other types of uses that have enabled the railways to perform and achieve its intended goal. It encompasses all associated features that aided its functioning either in its original or intended or designed form, or may have been modified or discontinued or relocated or assigned a new function. Irrespective of their present state, all such component parts are integral to railway history.

The existing norms do not facilitate the incremental changes that are normal for a railway station

Since initiation of operation, this multidimensional entity created a push-pull factor and pervaded all spheres of sub-continental life, dichotomously. From globalising the hinterland, to stimulating trade and technology, creating industries, cities, laying infrastructure and to initiating a cosmopolitan and consumer culture, the railways have significantly contributed to nation-building. Simultaneously, it also disconnected landscapes, created social (and economic) disparity, divided cities and denuded resources.

Railways are an ensemble of built and open spaces, with operational infrastructure and non-operational functions like residences, schools, colleges, clubs, hospitals et al. The interface between stations and a city had two transition zones: first a city-level public space and then a commercial area crossfading into residential, economic or industrial zones. In metropolises, stations led to banks, hotels, warehouses and business hubs through a network of public transport. In fact, railways were first-generation Transit Oriented Development where local, regional and international interests converged.

Railway heritage is more intangible and widespread than its built footprints. It pervaded all sectors and sections of society, lowered barriers, which reinforced our freedom of movement. From upward socio-economic mobility to fostering aspirations, the railways embodied the spirit of possibilities. Ironically, it also acted as a mnemonic prompt of a colonial past, perpetuated some unfavourable practices and spelt doom for others. Therefore, addressing this fact is as important as protecting the railways in their entirety as national heritage.

Stations were planned with provisions for expansion, which is an attribute of railway heritage. Therefore, equating an operational station to a monument and preserving it would be counterproductive. Archaeological heritage being the most popular typology of protected heritage, its technical standards, norms and approach are a common reference nationwide even for non-archaeological types, including the railways. Most works are therefore preservation-oriented to control change. Very few projects involve upgradation and maintenance, which is undertaken by the public works department and urban local bodies.

Railway heritage is more intangible and widespread than its built footprints

Indian Railways has developed a set of codes that envisage the future of railway stations and mainstream response to its heritage as an inherent part of the planning process. It ensures that the evolution of the site responds appropriately to heritage and adds value to it. These codes qualify heritage through its values, integrity and authenticity and then set limits of change. These codes were prepared by reconstructing the evolution of the station precincts through archival records and extensive field work, which were analysed in the context of the present requirements of passenger movements, multi-modal integration and other area planning measures.

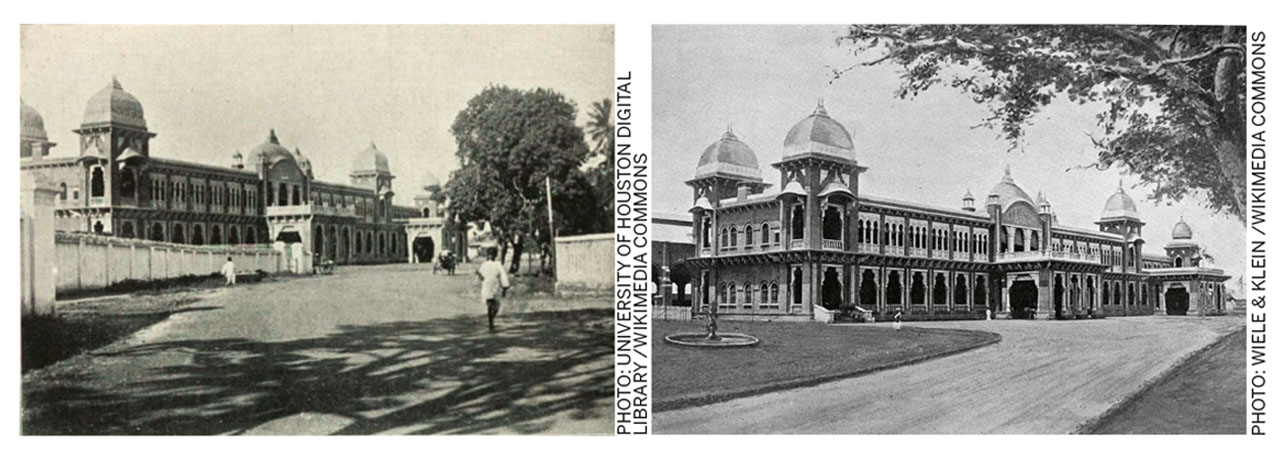

Different types of station areas were studied to generate, standardise and codify parameters and tools. These stations were selected based on their operational function, nature of ridership, geo-climatic conditions and era of construction. Based on these factors, stations can be classified as port, junction, terminal and halt stations. The most complex and elaborate variant were stations attached to international sea-ports. Following it in scale and complexity were junctions, terminals and then halt stations. Interestingly, several terminals were also converted to halts (like Egmore in Tamil Nadu) and port stations were often terminals and junctions (like Howrah). These were trade hubs, with road and canal ways, and with administrative and defence headquarters, large hospitals and sanatoriums, jails and courts. Most port stations, especially those of the presidencies, were built in classical European styles like the Italianate and Gothic with selected Indian royal symbols.

At capitals of princely states and provinces, junctions and terminals showed a hybrid of provincial features built on a European form. And, unless purely for defence functions, such stations always had a city-level public space leading to a sadar (large wholesale market) bazaar.

To intervene, retrofit or regenerate station areas will require addressing the interrelation of built and open spaces, with synchronised networks of mobility and public spaces during perspective or layout planning. The effective volume and form of development must respond to the context, be compatible with the socio-economic aspirations and encourage creative risk-averse solutions. Aesthetics also form an important determinant as stations were marker elements of a city and an embodiment of high design taste. Such details will specify the form and limits of developments and special consideration at the onset of project formulation.

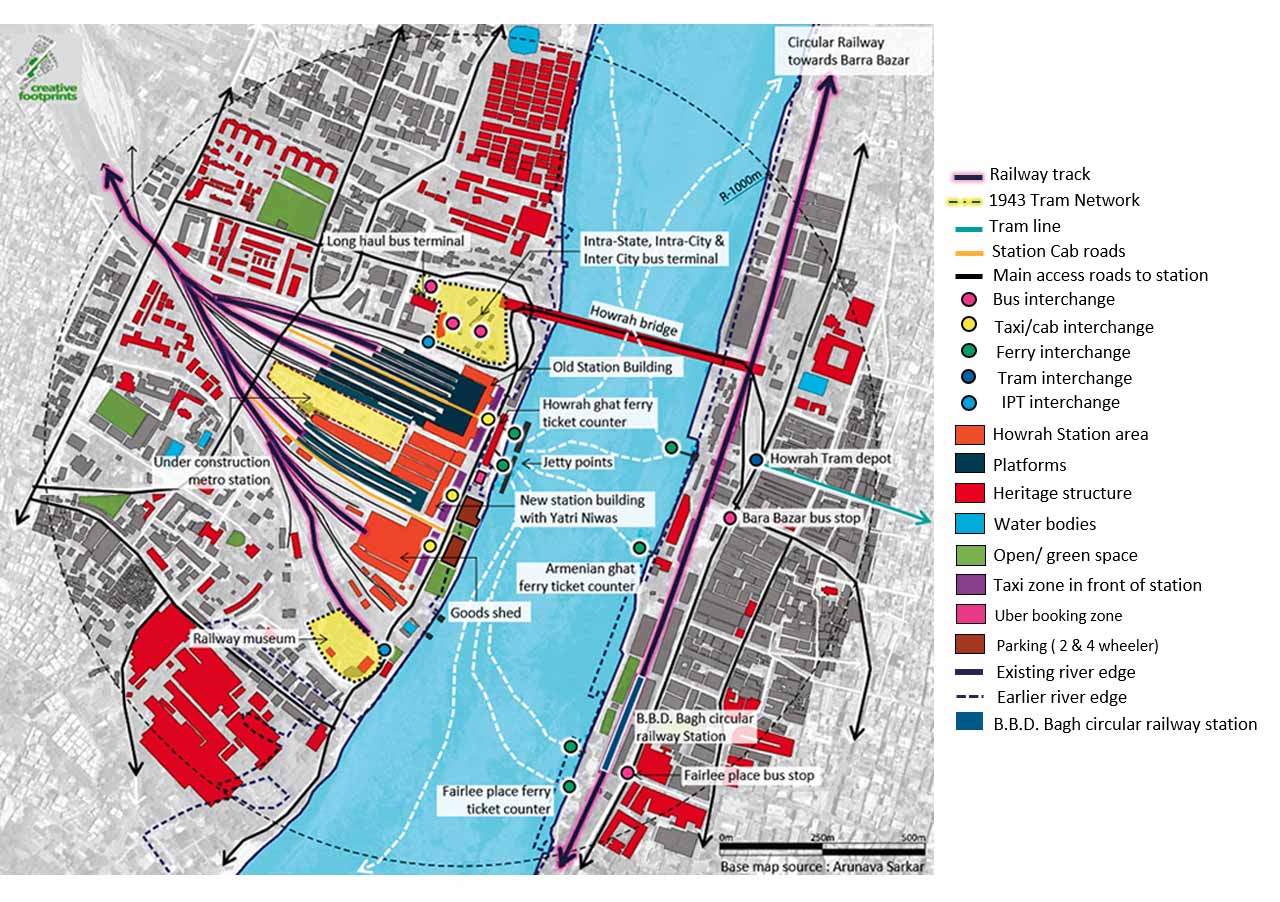

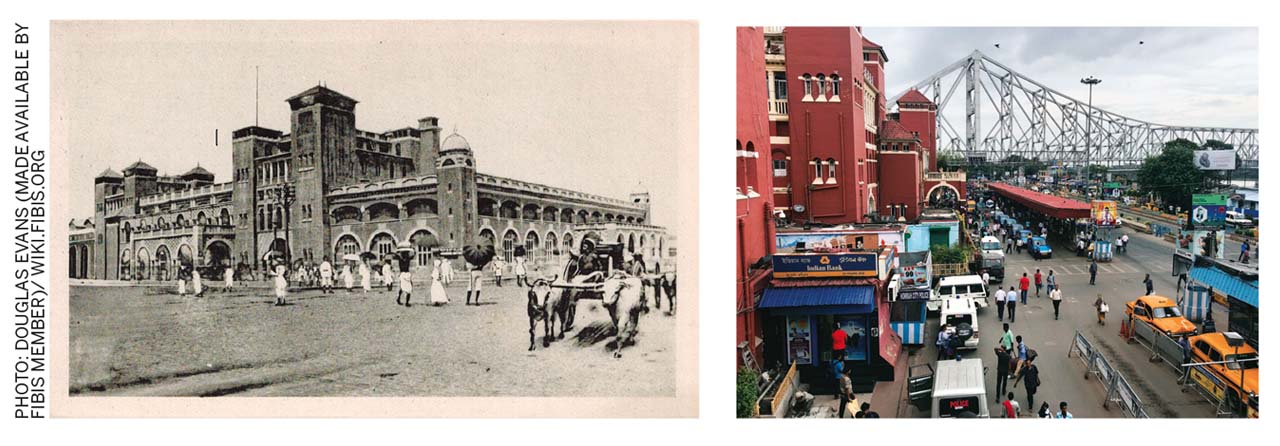

For example, any proposal for the Howrah terminal and junction port station should capture the value of the linkages between the station and its precinct that evolved in the early 1900s and the fact that it is eastern India’s busiest inter-change facility today. The change in movement patterns and growth in surface and sub-surface infrastructure show how an international network of trading ports, custom houses and corporate offices and industrial facilities like jute and cotton mills, factories for industrial machine parts, salt pans and producer areas in the hinterland interacted at the station area.

The station building is a marker element and functioned like an interface between platforms inside and the precinct outside. This created a symbiotic relationship, where the station building only hosts basic amenities to facilitate rail travel and is dependent on and instrumental in boosting business of the surrounding area.

A range of transport modes, commercial facilities, hospitality, healthcare and recreational services of different price-points are within walking distance. Over time, uses have intensified, diversified and sometimes atrophied. This is reflected in the movement and fluctuations of footfall. Hence, layout planning will incorporate these as determinants to project the future.

This is very different from opportunities offered by the Kalka-Shimla Mountain Railway line. Operational since 1903, it mainly ferried British officers to the summer capital Shimla, and its stations were mere pitstops. Today, it is a World Heritage Site and its riders are mainly tourists. Any upgradation of the station or its rolling stock must comply with World Heritage protocols and a typical expansion is unlikely as there is no space.

For instance, the layout of Shimla station was designed to direct passengers towards the army cantonment, the Ridge and the bazaar. Conventional financial modelling considers this a loss to the exchequer. If it had been adapted as urban-hill-transport, it would on one hand save the heritage and on the other, put it to a more viable use. This idea when proposed for Gwalior’s light railway services yielded encouraging results.

At a component level, a survey of the Dehradun terminus provided interesting information on how station buildings and their infrastructure were modified due to changing purpose and technology. Though a terminal today, this station was designed as a halt station with a small-sized public space mainly for the army and those traveling to Mussoorie. When its extension failed, the station was expanded to host functions and the city engulfed it from three sides. Today, at peak hours, the station area gets congested, decreasing prospects of value-capture.

Considering the above, compatible and adaptive continued use of stations is crucial and should:

- Not compel permanent alteration of existing layouts, built volume or that which defines its character. For example, the ‘public’ face of a station is sacrosanct and extensions and new constructions must ensure its visual dominance. This is achieved through planed view corridors, contextual architectural design and manipulations of new volumes at the layout planning level. This will also indicate the scope for value-capture.

- Not require irreversible transformation of structural, spatial, architectural and ornamental systems or that which comprises a character-defining feature.

It is to protect the inherent diversity and significance of built heritage characteristic of the railways through high quality design application of technology. And, as such projects offer increased visibility, they should encourage competency and industry participation.

- Keep in the forefront the spirit of independence and the ability of the railways to steer growth. This makes it imperative to select a function and subsequent use that are socially relevant and integrative, linking the railway with its context. Uses that are exclusive and non-circular are against the spirit of the railways.

- Capture all revenue streams and accentuate the multiplier effect inherent to the railways. This would require proposals to be light-footed and flexible to account for the gap in time between project planning and implementation. The project horizon being 40 years, conservation plans must provide indicators to assess relevance of proposals.

- Not compromise the degree of adaptability of the whole or part of the heritage. This restores the right of the future generation to access heritage in its true form.

- Conveying original function and use or its intent is fundamental to communicate its importance. It also sanctifies the effort to safeguard its future.

Acknowledgement: This article is based on codes for station redevelopment including commercial development published by the Indian Railway Stations Development Corporation Limited. The codes are funded by the Shakti Sustainable Energy Foundation and prepared by Creative Footprints, New Delhi.

Comments (0)