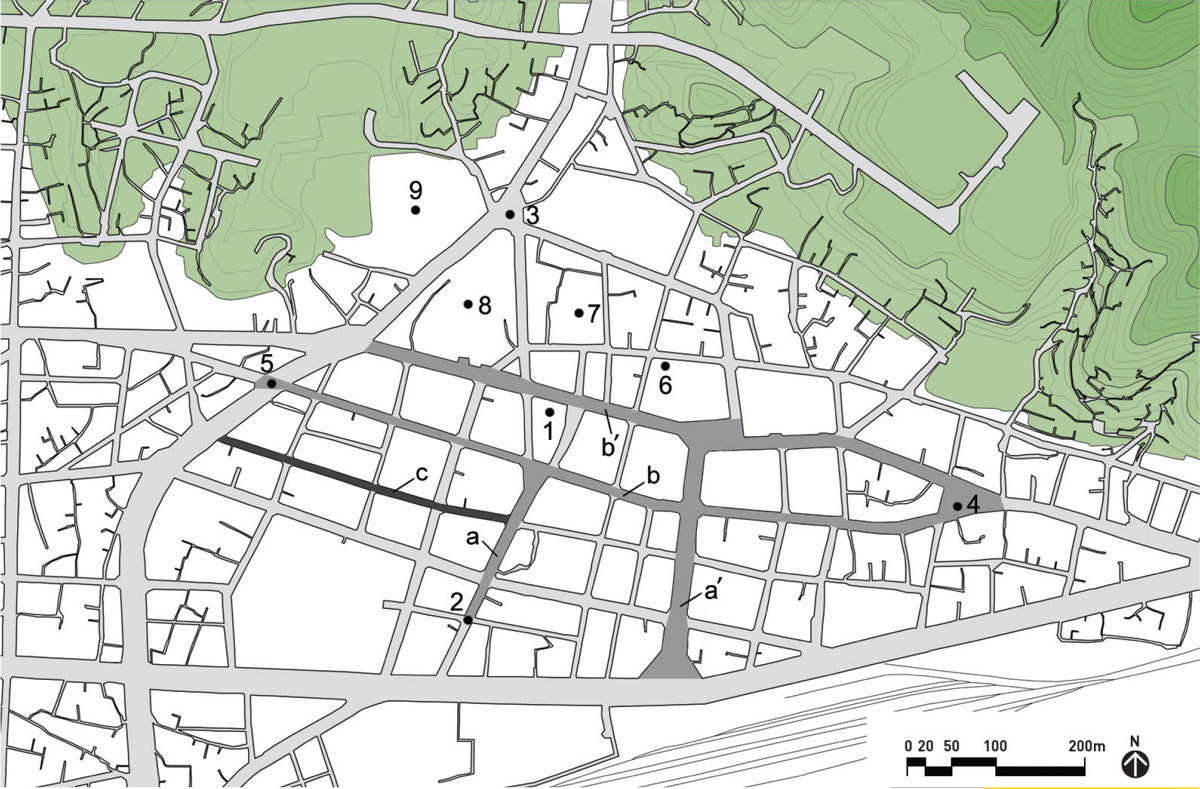

Two Axes

Historic Korean cities, including the capital city of Seoul as well as the city of Andong (one of the representative historic provincial cities located in Gyeongsangbuk-do province), typically have two main axes: the longitudinal axis, a main street usually running approximately north-south (hereinafter called the south-north street) and the transverse one, another main street usually running approximately east-west (hereinafter called the east-west street). The south-north street connects the south gate, the main entrance of the walled city as in Seoul and Andong, and the symbolic institution of the ruling power, Gyeongbokgung, the main royal palace in Seoul, or the Gaeksa, the official guesthouse where the Royal Tablet, the symbol of the king, was enshrined in other provincial cities. Many of the government office buildings were located in front of or beside the symbolic institution.

As the Joseon Dynasty ended in 1910, the modernisation of many provincial cities was heralded by the change of the Gaeksa into a modern public facility. In most cases, the Gaeksa was reused or demolished to be rebuilt as an elementary school, which was an institution for the Japanese colonial education, though in Andong the city’s first bank was built in 1920 on the site of the Gaeksa. In the case of Seoul, the Blue House, the Korean presidential office and residence, was built behind the Gyeongbokgung.

In historic provincial cities like Andong, the transformation of the Gaeksa was followed by the construction of a new bigger set of main streets parallel to the existing ones, that is, the duplication of the two old main streets instead of widening them. These two newly constructed main streets echo the meanings of the existing ones respectively, which will be addressed below.

1. Gaeksa

2. South gate

3. North gate

4. East gate

5. West gate

6. Symbol tree

7. Shrine of meritorious retainers

8. City health centre

9. City hall (old site of Public Confucian Academy)

a. South-north street

a’. New south-north street

b. East-west street

b’. New east-west street

c. Market street

Right: Fig. 3: Old marketplace of Andong (c in Fig. 1) at night

That construction was necessary because of the increasing traffic in the modernising city, which could not be accommodated in the narrow existing main streets. However, in Seoul, there was no duplication of the main streets. This is because in the beginning of the 15th century, the two main streets of Seoul were planned and constructed as wide as possible to potentially accommodate the traffic of a modernising Seoul.

By duplicating a set of main streets rather than widening existing ones, the old main streets, especially the east-west street, could sustain intimate human scale that makes the street function as an integrating element rather than just a path or an edge of a district.

In Andong, the width of the old east-west street, named Jungang-ro, meaning the central road, is eight metres, which allows all audio-visual perception and smell, as well as verbal and non-verbal communication between the spaces along both sides of the street. This pattern of urban growth, duplicating the main streets, has led to the special quality of old provincial cities in Korea, where a street does more than concentrate specific activities along it, being itself an urban setting for diverse activities. (Fig. 1-3)

The south-north street has been a ceremonial or political axis; in the past it was a setting for official events such as the local governor’s inaugural parade. The parade – in which the local governor was accompanied by a colour guard, petty officials, servants and a brass band – would end with the newly posted governor bowing to the Royal Tablet at the central space of the Gaeksa located at the end of the street. Through these kinds of ceremonies, the royal power was exhibited on the south-north street. The ordinary citizens walked along this street only when they were carrying the bier (a moveable con). In many historic Korean cities including Andong, the south-north street, old or new, is still often used for political campaigns for the election of the president and members of the National Assembly. Thus, the character of the south-north street can be said to remain rather public and symbolic or political.

The east-west street connects between the east and the west city gates. It has been a daily or commercial axis accommodating ordinary people and their everyday lives. The marketplace that was formed along this street could be a venue for citizens to congregate and to have social contacts.

Since the 18th century, when trade began to flourish within Korean cities, this street has become densely populated with commercial buildings. With its transformation into a busy commercial street, the difference in character between the two axes, the south-north and east-west ones, was reflected in their shape and length. In many historic Korean cities, the south-north street, the ceremonial or political axis, is straighter and shorter while the east-west street, the daily or commercial axis, is often subtly curved following the flow of topography and is much longer. In Andong, the length of the latter is about four times that of the former. Both citizens and visitors would gather around the city gates, especially at marketplaces near them and move along the east-west street lined with shops. So, the east-west street has always been lively in contrast to the south-north street. In most Korean cities, it is still the east-west street, old or new, that is busiest and most commercial. The east-west streets usually sleep very late, because they support the lively night life in Korean cities. (Fig. 1-3)

Intersection of the Two Axes

The two axes, the south-north and the east-west streets, typically intersect in front of the symbolic institution, the place of ruling power, which was the main royal palace in Seoul or the Gaeksa in other cities, until the end of the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910). In the past, the subjugated citizens would avoid bumping into the rulers who resided nearby. The intersection offered the most open space in the city but was not a place of gathering.

The story has now changed as political power has shifted from the royal authority to the public. Korean citizens are free to recognize and express their political viewpoints and now the intersection of the ordinary and political axes is regarded in a new light by citizens. It is interpreted as a meeting point of everyday life and politics, where they can gather to share their thoughts with the government.

The open space at the intersection also supports diverse cultural activities such as outdoor exhibitions and performances including busking.

In Andong, it was the venue for folk games until the beginning of the 20th century and it is now frequently used for citizens’ cultural activities. Accordingly, a small open space at the intersection evolves into a plaza that accommodates more people and their political or cultural activities. Given that, historically, Korean cities, unlike Western ones, did not have a physically defined plaza as a public open space, this can be regarded as a new type of open public space in the Korean city.

Most of the big political gatherings and mass protests in Seoul happen at Gwanghwamun Plaza, which has evolved from the intersection of the two main axes. It was originally a wide street, flanked by the offices of six ministries of Joseon, from Gwanghwamun Gate to Gyeongbokgung Palace, to the intersection of the south-north and the east-west streets. The plaza was opened on August 1, 2009 after a renovation that downsized lanes of traffic, from 16 to 10 lanes, to make a wider open public space. Since the renovation, it functions as a national centre for participatory democracy in that most of the national-level political issues are debated and demonstrated here. In fact, the recent political turmoil and change in Korea with the impeachment of the former president Park Geun-hye and election of the new president Moon Jae-in in 2017 was driven by continuous candlelight vigils that happened at Gwanghwamun Plaza from October 29, 2016. There were political demonstrations or events almost every day. (Fig. 4)

As described above, the open public space at the intersection of the south-north and the east-west streets has become a hub that keeps the city vibrant. The extent of the linear spread of urban vitality from the intersection along the south-north and the east-west streets can be regarded as a barometer of the political and economic power of the city. Thus, the city governments of Korea are eager to encourage the power of city and they often take up a challenge: to make the main streets pedestrian-friendly, considering Koreans are highly dependent on their vehicles.

Golmok Fabric and Liveability

The observations in this article lead us to the conclusion that a network of main streets and linear spaces, rather than districts and planar spaces delineated by streets, make Korean cities vital and dynamic.

The main streets and the districts behind them are different from one another in terms of use, atmosphere and meaning. The districts are basically residential areas that are finely interwoven by alleyways or golmoks, which are diverse in shape and length. The golmok, narrower than four metres, sometimes as narrow as 80 centimetres, is enclosed by a series of neighbouring houses that are accessible directly through it. And the dwellers of the houses, who have social contacts daily by sharing the same golmok as a common space, make up a small community.

There are two types of golmok in Korean cities: the through golmok and the dead-end or cul-de-sac golmok. A cul-de-sac, denoting a street closed at one end, is originally a French term meaning bottom (cul) of the bag (sac). In contrast to its frequent use in modern residential planning to limit through traffic, the cul-de-sac has not been historically dominant in many cultures.

It is not generally found in historic Chinese cities. It was, however, developed in the early stages of Korea’s urbanisation, as part of a dominant pedestrian network for individual houses making up the fabric of urban settlement. Cul-de-sacs remain well sustained in many historic Korean cities such as Seoul and Andong (Fig. 5). They tend to follow existing contour lines with their specific forms closely related to topography (Fig. 1). In many historic Korean cities, one can easily identify cul-de-sacs of diverse widths, lengths and shapes, some so narrow that two people can barely pass by, creating an intimate human scaled space lined with single story houses.

Today, residential golmok fabrics do not conflict with the network of the main streets that have gradually taken on a clearer geometrical form in modernising Korean cities. In fact, golmok fabrics provide individual access to houses often sited irregularly on the natural terrain, creating tranquil and safe residential enclaves that exclude through traffic, either pedestrian or vehicular. They bear a strong social meaning, structuring the urban settlement into groups of smaller communities, each with several households. Residents around the same golmok share a strong sense of community. The golmok itself is a kind of outdoor multi-purpose room for the community members, an informal neighbourhood meeting and play space for children, a semi-private communal space mediating private houses and public streets and avoiding the abrupt shift between public and private spaces so common in contemporary cities. It is deemed to be a key element that makes Korean cities liveable.

Comments (0)