This spread is a series of mappings that helped me understand the morphology of San Francisco, one of the most prominent cities along the west coast of North America, which is known worldwide as a centre for innovation in business, technology and digital culture, as well as a place where art intersects with all three.

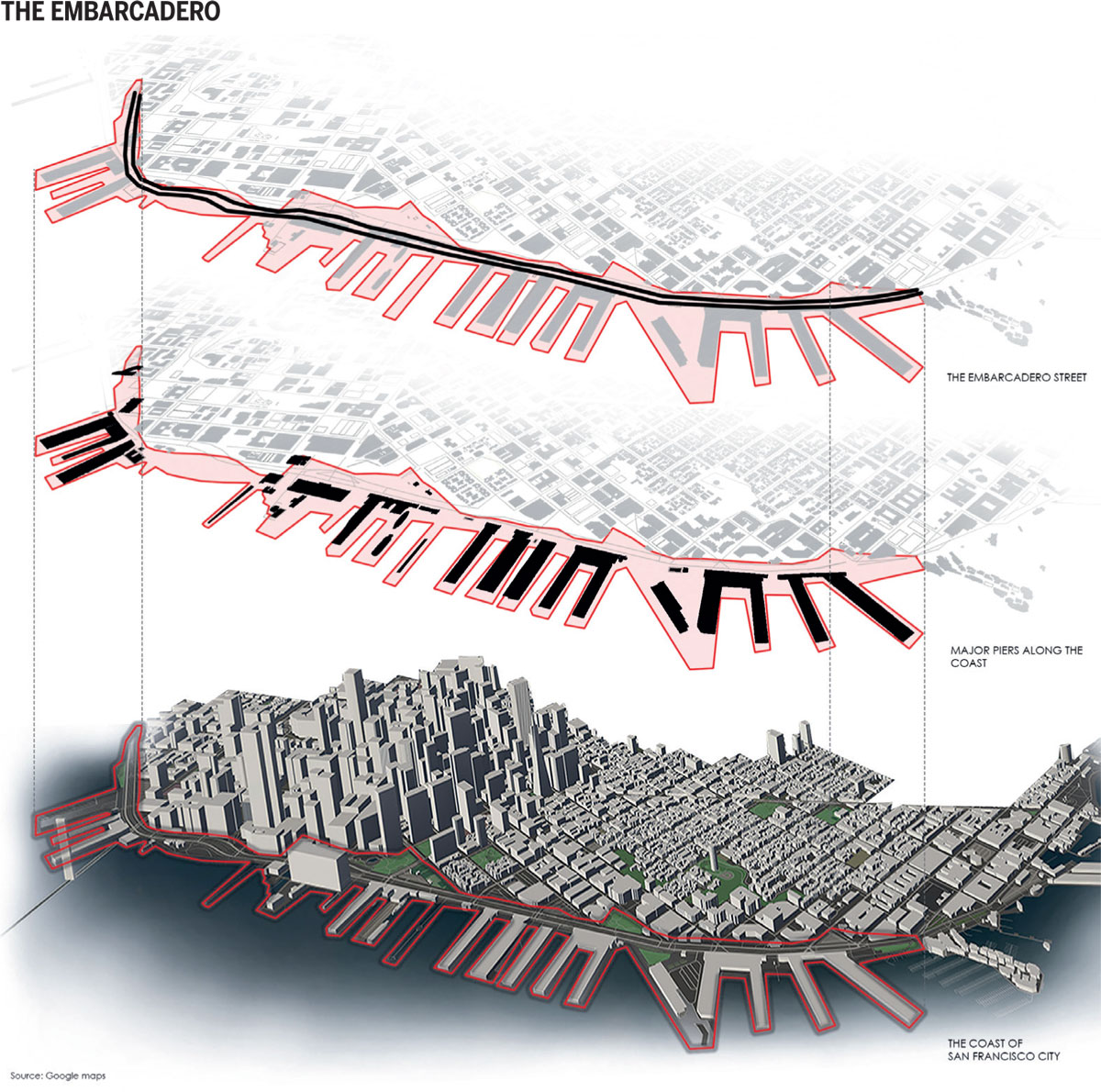

Within San Francisco’s 49 square miles, visitors will find a wide range of film festivals, art, architecture and design events, comedy, literary and music festivals, dance festivals and a myriad of theatre, ballet and other opera productions. The Pier 24 at Embarcadero Street houses various exhibitions including the Pilara Foundation’s jaw-dropping collection in addition to exhibiting ambitious but accessible shows of historical and contemporary photography. The area, stretching roughly half a mile north of Market Street and bounded by the 101 to the west and Montgomery to the east, includes some of the most established as well as a few of the hippest and most innovative galleries in San Francisco; it also has some of the best venues for viewing Asian art. As a contrast to these areas, the city also has an area where the homeless and the drug users find refuge: The Tenderloin. It is described as ‘hopeless’ and ‘lost’ and a place that must be avoided at all costs.

The footprints of the Gay Rights Movement line its streets and so do the footprints of mid-century jazz legends, rock and roll hall-of-famers and boxing greats. The Tenderloin, with its mural covered walls on one side and dingy sidewalks on the other, remains an area of irreconcilable contrasts and confounding mysteries. The Civic Center or the Central Market area of San Francisco houses professional opera, symphony and ballet companies. These are located in historic venues opposite the City Hall; the artfound here is as resplendent as the area’s Beaux Arts architecture.

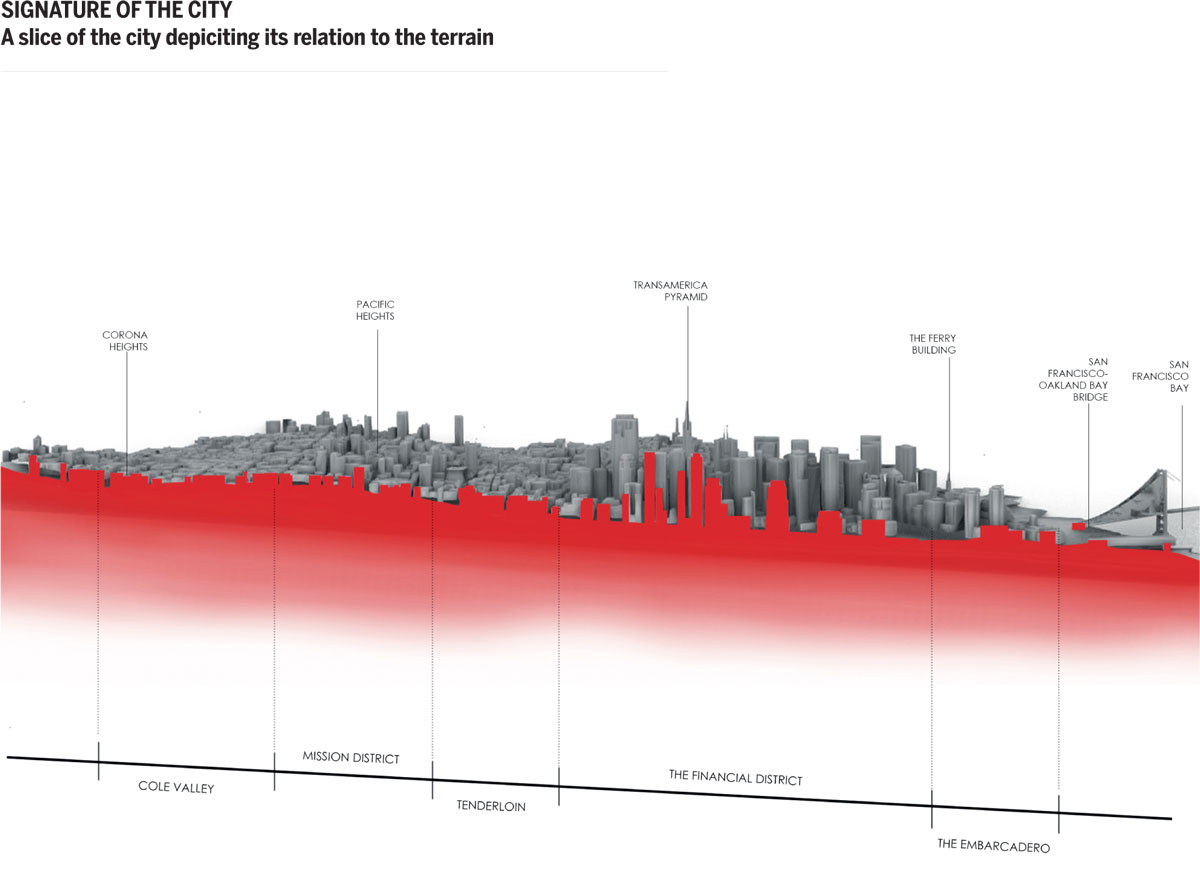

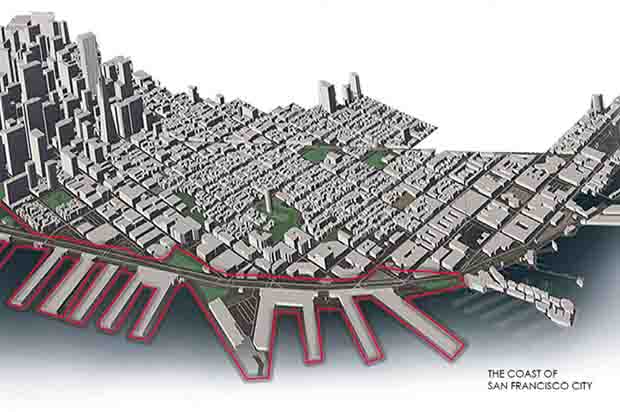

A slice of the city depiciting its relation to the terrain

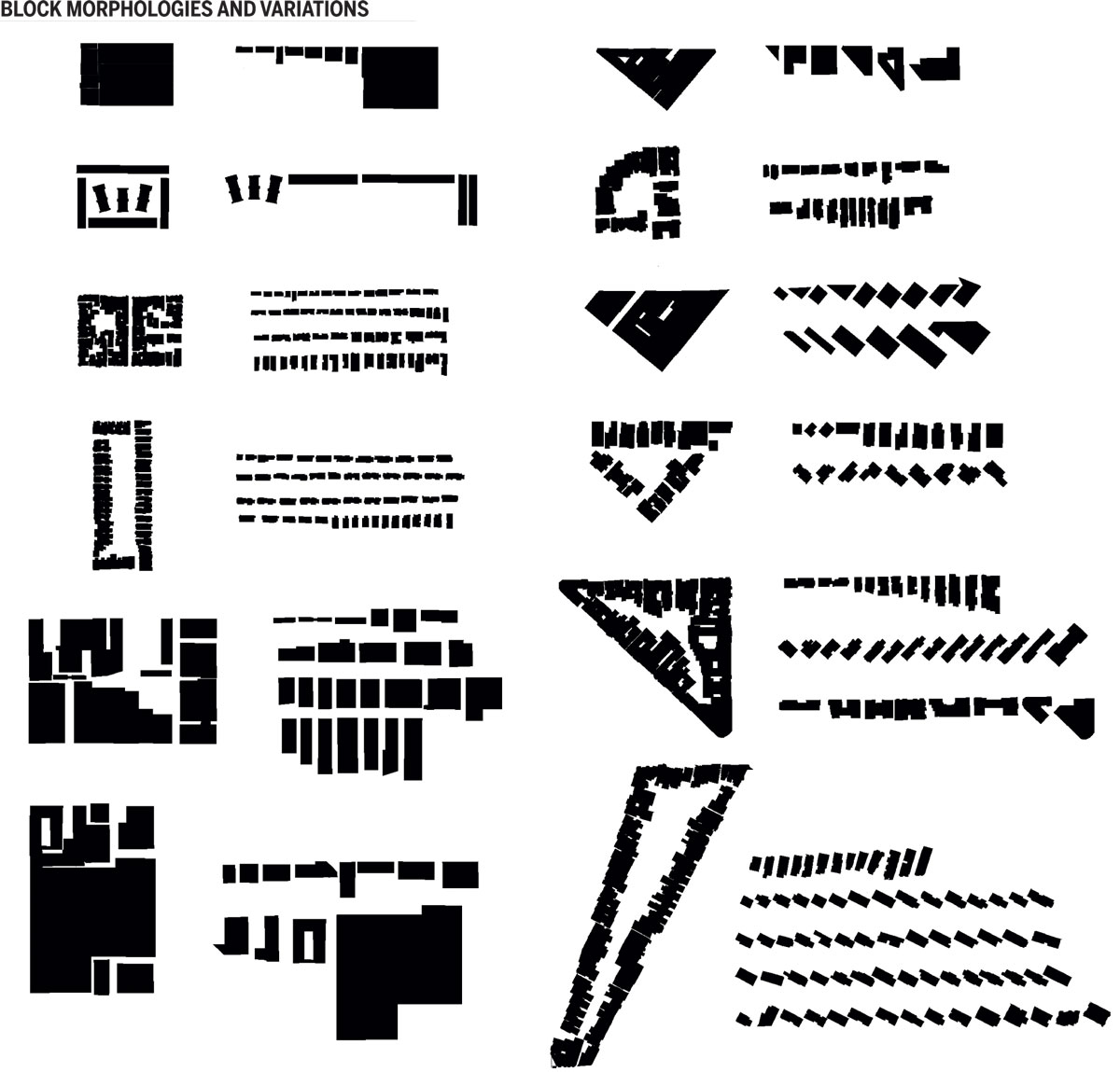

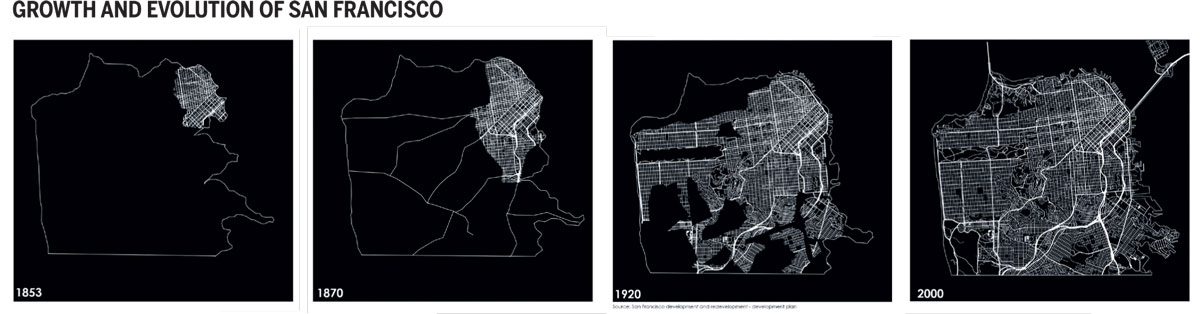

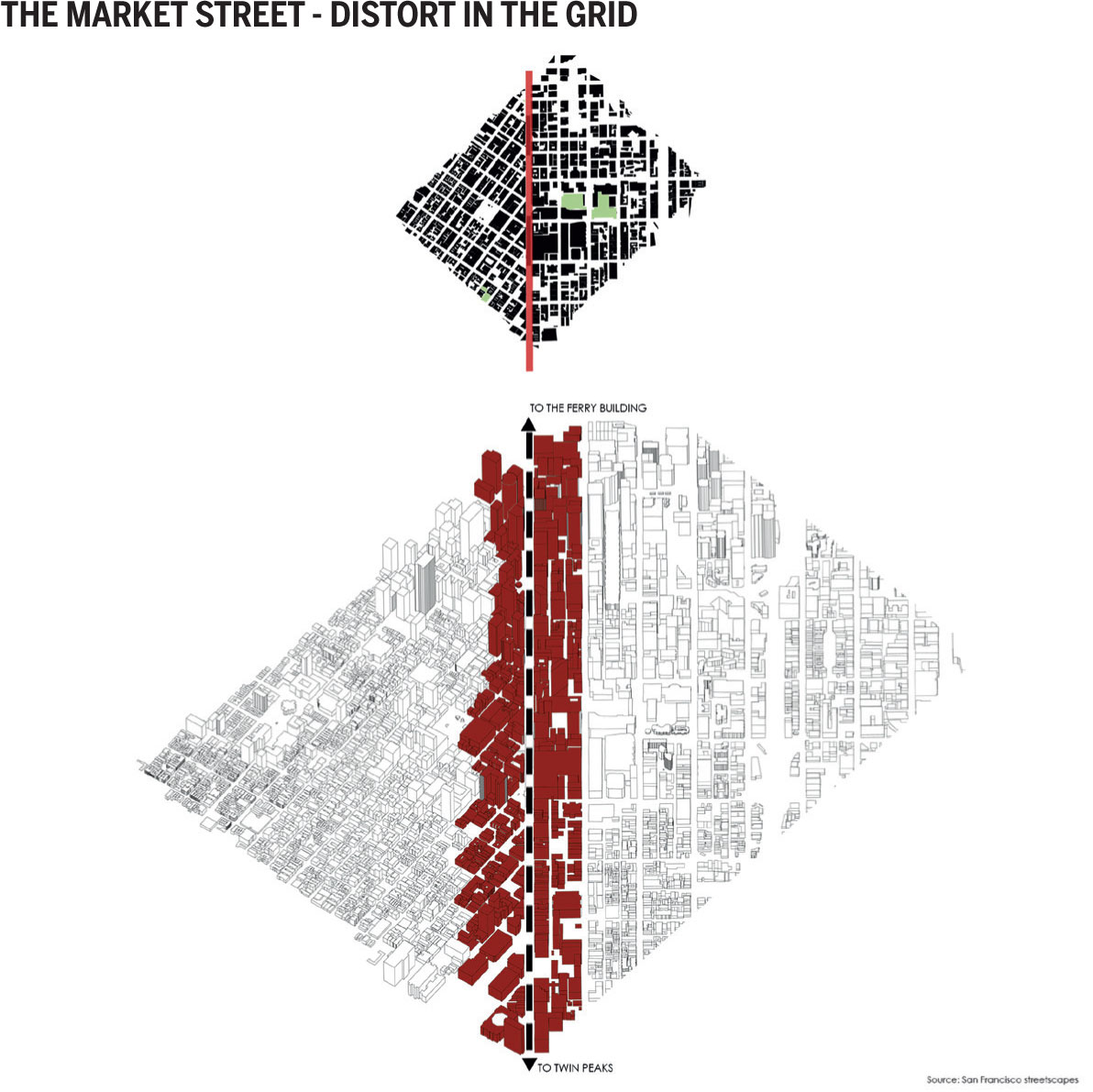

San Francisco’s varied urban form and neighbourhoods may be attributed to features like geography, changing housing patterns, transit lines and the major earthquakes and fires that hit it back in 1906. Its grid pattern, which seems to be imposed on a city of hills at the end of a peninsula, generates streets and neighbourhoods that are divided from one another in separate valleys across its small area. These streets and roadways add to the overall character of the city by means of providing vistas and open spaces and also determine the character of growth and development across the neighbourhoods. Some of its most famous structures include the Golden Gate Bridge, Coit Tower and Ferry Building, which stand as important symbols to the community from the otherwise dominant pattern of a gridded fabric stretched across its undulating landscape.

Comments (0)