For over 50,000 years, mostly nomadic aboriginal tribes inhabited Australia. These tribes lived in such harmony with their local landscape that they managed and understood its subtle ways. The arrival of Europeans, just over 200 years ago, saw rapid changes with all the existing major Australian cities being developed around the coastline where ports were important, water was available and the land was generally fertile and the climate more moderate.

Towns and cities away from the coast have been created on transport routes or to serve agriculture and mining from the gold rushes of the 1950s to the resources boom of recent decades. Inland Australia is largely hot and dry with limited water and ancient soils that are not suitable for agriculture except for grazing of livestock at low densities. Climate change will create pressures on inland and coastal Australian cities in different ways. Canberra is a relatively young city, just a century old. It is Australia’s largest inland city but it is still small in population.

Climate change will create pressures on inland and coastal Australian cities in different ways

Canberra is a new capital city in the mold of Washington, Chandigarh and Brasilia. It is also a city in the spirit of the garden city movement designed to sit within its landscape setting while also containing the symbols and institutions of a national capital.

The site was selected as a compromise between established rival cities Sydney, New South Wales and Melbourne, Victoria, Australia’s two biggest cities then and now. It is situated in the Australian Capital Territory, in southeast New South Wales. One of the reasons that the government wanted an inland capital city was that Sydney and Melbourne are both susceptible to sea attacks. The name Canberra was derived from a word meaning ‘meeting place’ in the language of the local aboriginal tribe.

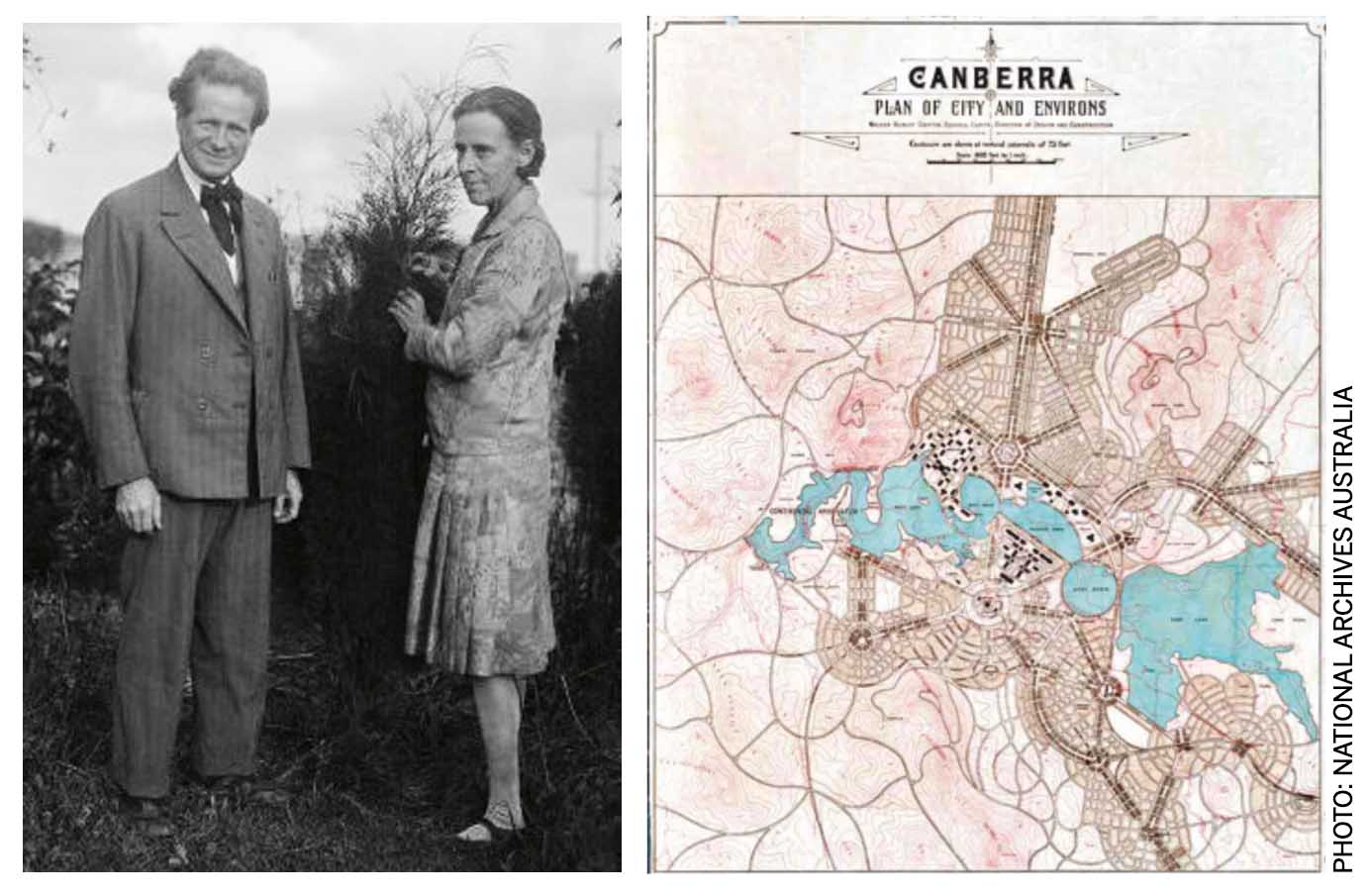

A design prepared by 35-year-old Chicago landscape architect Walter Burley Griffin and his architect wife Marion Mahony Griffin was selected from 137 entries to an international competition in 1912. The second prize was awarded to Eliel Saarinen of Finland.

Burley Griffin’s design for the new city was carefully conceived to fit and respond to the natural landscape

Right: The Burley Griffin plan proposed a formal triangle of axes between three hills with the Molongolo River in the valley being dammed to create a lake

The brief required the development of a city for 25,000 people from open farmland. Burley Griffin’s design for the new city was carefully conceived to fit and respond to the natural landscape with three hills becoming the focus of triangular axes and with the valley to be reshaped to form a lake. Symbolic elements of this city plan included the parliament, the city and a military college. Griffin and his wife moved to Australia in 1913 and had a design advisory role as well as the right to practice. They stayed in Australia until 1935 when they moved to Lucknow, India, where he had been commissioned to design a university library and other buildings. Burley Griffin died in India in 1937 and Marion returned to the United States.

The Griffins left a legacy of great buildings and landscapes in Australia but difficult politics and the Great Depression limited their influence over the development of their plan for Canberra.

The key ideas of a city that respects, and is subservient to, its landscape setting, has lived on in the development of the city to this day. Its design and development were also greatly influenced by the garden city movement and it can be seen as a fine example of suburban car-based planning. After 100 years of development it is now just starting to manifest more urban qualities familiar in larger cities.

Today, Canberra remains the centre of government in Australia and is its eighth largest city with a population of over 400,000 people. All land remains in public ownership with a leasehold system giving the government greater planning control than anywhere in Australia.

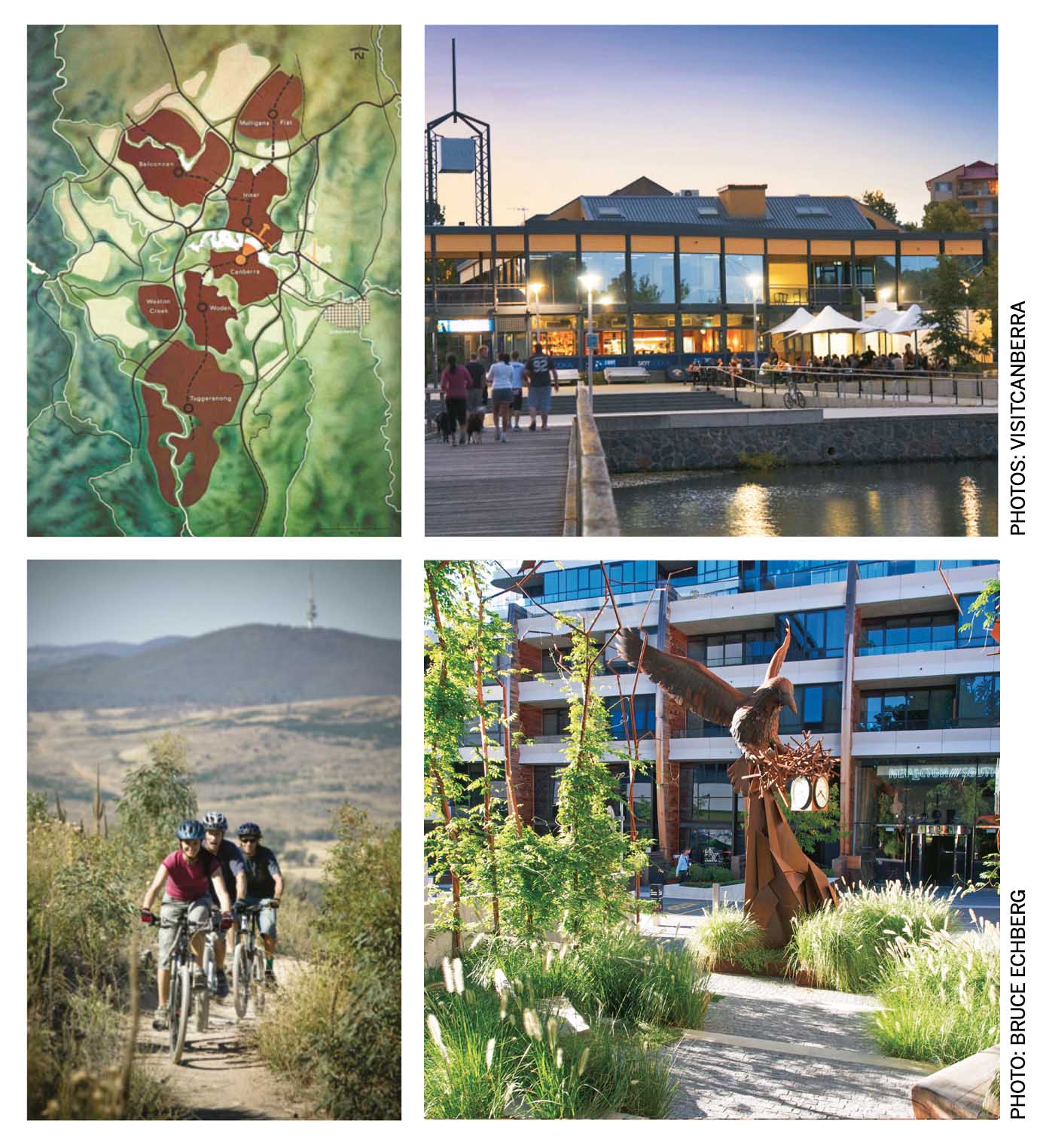

During the 1970s, the Y plan for expansion of the city was conceived and its development began. This was a linear plan for the development of new towns to the northwest and southwest of the existing urban area linked by a generous system of landscaped roads or American inspired ‘parkways’.

Open space systems are carefully planned to enable safe walking and cycling to schools and local facilities

These new towns have developed as self-sufficient town centres surrounded by open space and a network of neighbourhood centres with their own local schools, services community and open space. This linear Y plan concept plans the growth of Canberra to beyond 500,000 people without sacrificing the spatial qualities and design of the original Burley Griffin city at the centre of the Y. Open space systems are carefully planned to enable safe walking and cycling to schools and local facilities. There is even a network of horse riding trails through parts of the city.

Bottom Left: Canberra sits within protected natural landscape with hills and ridgelines kept free of development giving residents good access to nature but also making urban areas vulnerable to bushfires. Canberra is close to national parks within alpine areas that become ski fields in winter

Top Right: Belconnen is one of the new towns with its own lake, commercial centre and a university.

Bottom Right: New Acton- A high-density mixed-use redevelopment within the original Civic Commercial Area that has sustainable buildings and revitalised public space between old and new buildings

In the 1970s, the growth of Canberra coincided with the establishment of the landscape architecture profession in Australia and it is here that the influence of the British profession was greatest with Sylvia Crowe designing Commonwealth Park on the north edge of Lake Burley Griffin. Most planning and design of the new towns and neighbourhoods involved landscape architects from inception, setting an example for the rest of the country.

While development of these new towns is very well planned by Australian standards, the density achieved is similar to most other Australian urban growth areas at 15 dwellings per hectare, which is generally regarded as well below the density that is sustainable without the use of the car as the dominant mode of transport.

THE PARLIAMENT HOUSES

A temporary parliament building was developed early on and opened in 1927 to enable the National Parliament to move from Melbourne where it had been since the federation of the states combined to create the nation of Australia in 1901.

Bottom: The Australian War Memorial - Developed to commemorate Australian soldiers who lost their lives in the First World War. It was not opened until 1941 at the outset of the Second World War

An international competition was held in 1979 to design the permanent building on Burley Griffin’s Capital Hill site. Mitchell Giurgolo Thorp, who was selected from 329 entries, won the competition. The new parliament was completed and opened in 1988. It is essentially a 4500-room building set down into the landscape with a grass roof surmounted by a symbolic flagpole. Like Canberra itself, the building is fully integrated into the landscape-inspired city design in the spirit of the Burley Griffin plan. The public can walk on grass lawns over the parliamentary chambers and the entire building and car parking is subservient to, and fully integrated with, the site landscape.

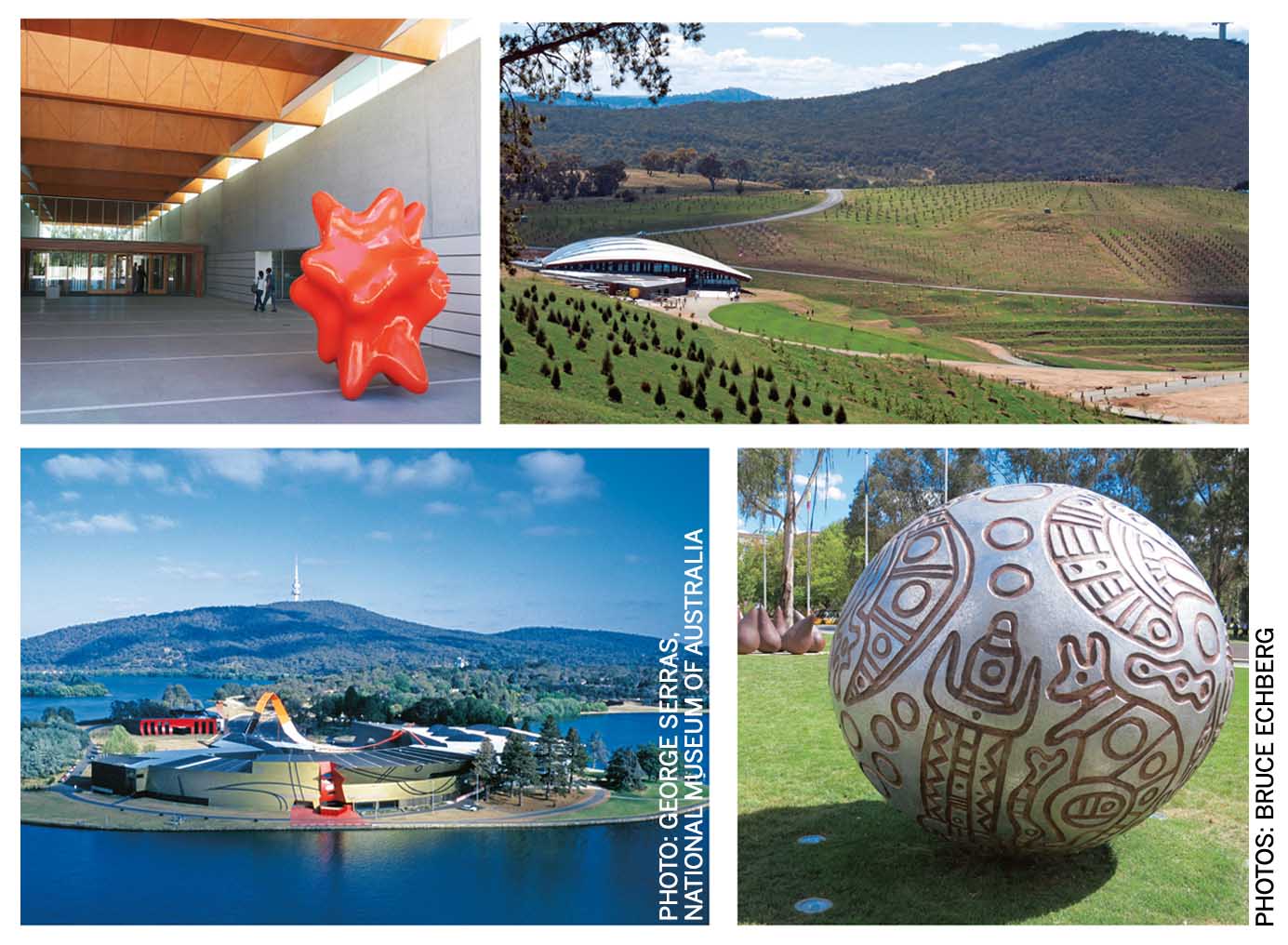

Other significant national buildings are carefully located around Lake Burley Griffin. They include: The Australian War Memorial, National Museum of Australia, High Court, Australia, National Gallery of Australia, National Portrait Gallery and the National Arboretum.

The community is very protective of its current character, which is more car-based and suburban than that intended by Burley Griffin in 1912

Top Right: National Arboretum - It was created after bush fires destroyed part of the site leading to an international competition in 2004 won by Taylor Cullity Lethlean landscape architects, and architects Tonkin Zulaika Greer. The site includes a cork oak forest created in the early years by Walter Burley Griffin who sent a supply of acorns in 1916 from Melbourne because he recognised their potential and wanted Canberra to become self sufficient in cork

Bottom Left: National Museum Australia - Aerial view

Bottom Right: National Gallery of Australia - Sitting opposite the High Court was designed by Edwards Madigan and Torzillo. It opened in 1973 and houses

a significant national collection. The surrounding gardens form an important part of the collection and are a significant designed landscape

FUTURE CANBERRA

While Canberra lacks the scale, density and coastal setting of the other bigger state capital cities, it has a lot to offer visitors and is a great place to live because of its well-considered planning, its high quality amenities and a city lifestyle with a close connection to the landscape.

The challenge for Canberra is how to accommodate significant future growth while at the same time containing its footprint, and reducing its dependency on the private car. This is beginning to happen with areas of higher density development and consideration of the introduction of a light rail system, which would be a relatively simple project within such a strong, well defined urban structure and protected landscape setting.

The community is very protective of its current character, which is more car-based and suburban than that intended by Burley Griffin in 1912. Change in the form of much higher density development within the existing Canberra footprint is possible but it will be difficult to negotiate with such an articulate and educated existing population that values the city’s natural landscape and open spaces.

Comments (0)