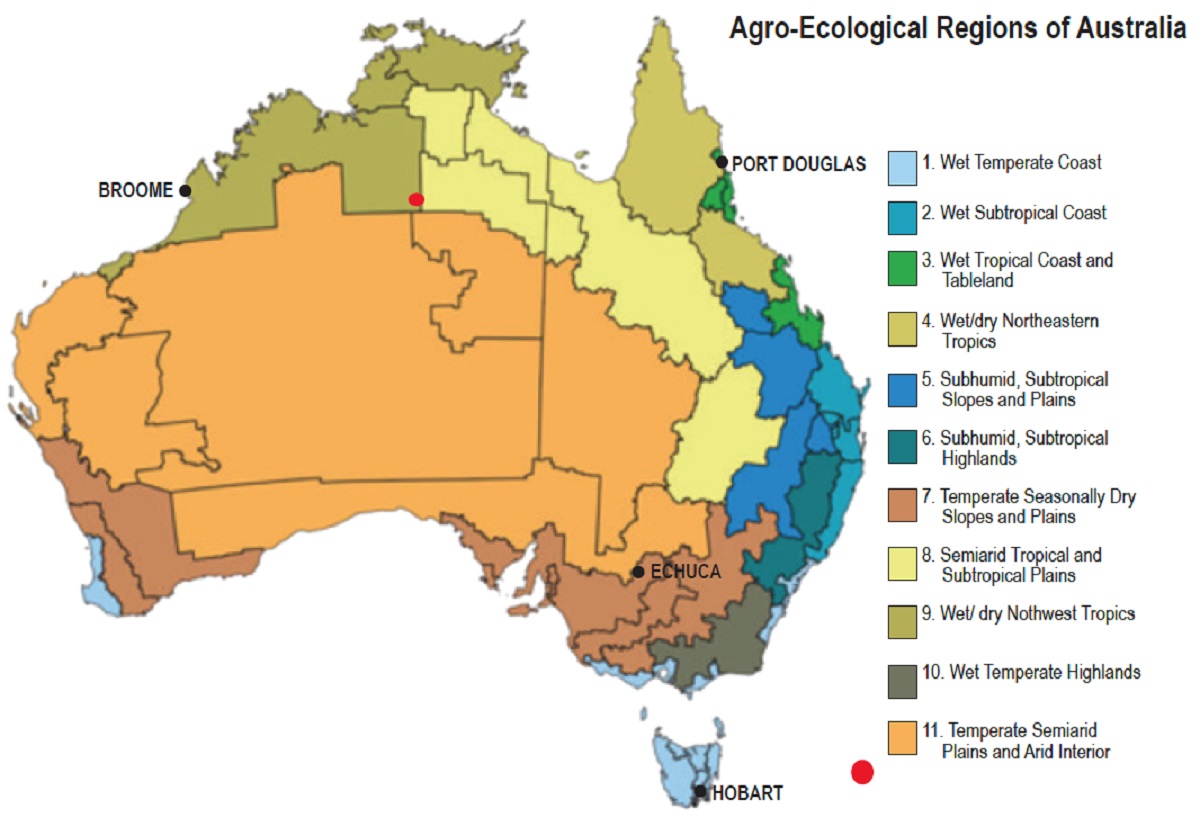

Australian cities have all been developed over a relatively short time span – less than 250 years since the first European settlement – and most rapidly during the era of the car that has dominated city planning since the 1950s. The post-World War II period has also been the era of international design when ideas moved freely and materials and products were universally available. The major variables for Australian cities and towns are climate and landscape; these do influence the character of settlements significantly. Buildings and public space need to consider the climate, which in Australia can extend from occasional snow to the monsoonal tropical climate of wet and dry seasons.

Coastal areas where the vast majority of Australians live tend to be more fertile with higher rainfall while the vast inland of Australia depends on the river systems and can be hot and dry desert plains or forested mountains with landscapes in-between. In addition, each city reflects its history; those which developed as a result of mining or agriculture vary from the ports and transport centers, which are different again from those with government functions or those growing from tourism.

Planning and architectural fashions of different eras also shaped the character of towns.

This article selects four towns and cities, of greatly different size, history, siting and climate, in an attempt to understand the ways these factors have contributed to the character of each one. Only one of them, Hobart, is a capital city, the others being regional towns or cities.

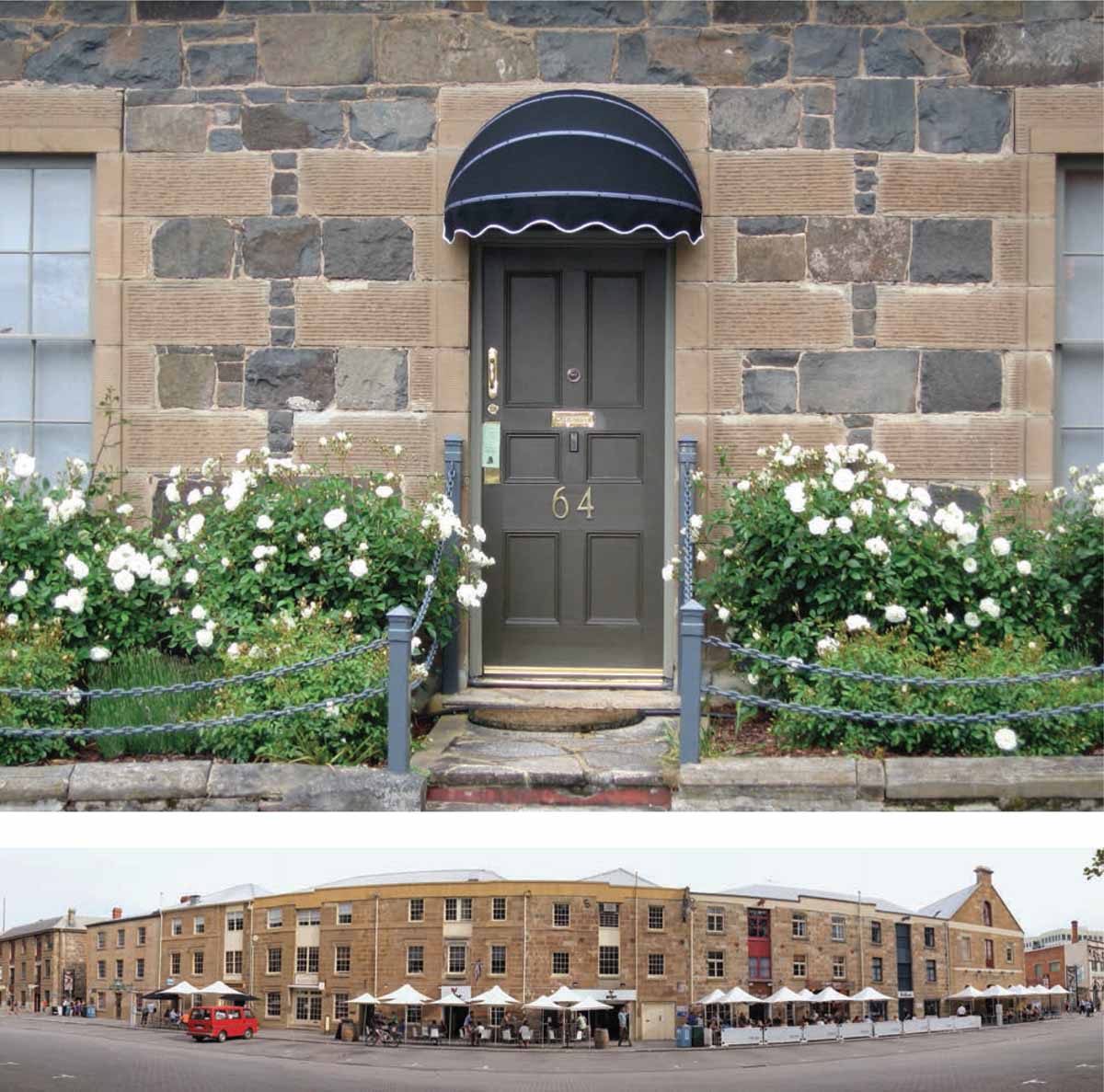

Bottom: The Georgian architecture of Salamanca Place, former waterfront warehouses, has been adapted to new uses for tourism and hospitality

Hobart

Hobart is Australia’s most southern city and capital of the island state of Tasmania. It was founded in 1803 as a penal colony and is the second oldest state capital city after Sydney. It is also the smallest with around 220,000 residents in 2015. It sits on the Derwent River, which was one of Australia’s finest deep-water ports that serviced Southern Ocean whaling and sealing trades in the early years and is now a service center for fishing and research in the Antarctic. Hobart has a mild, temperate, oceanic climate and sits at the base of Mount Wellington that is often snowcapped in winter.

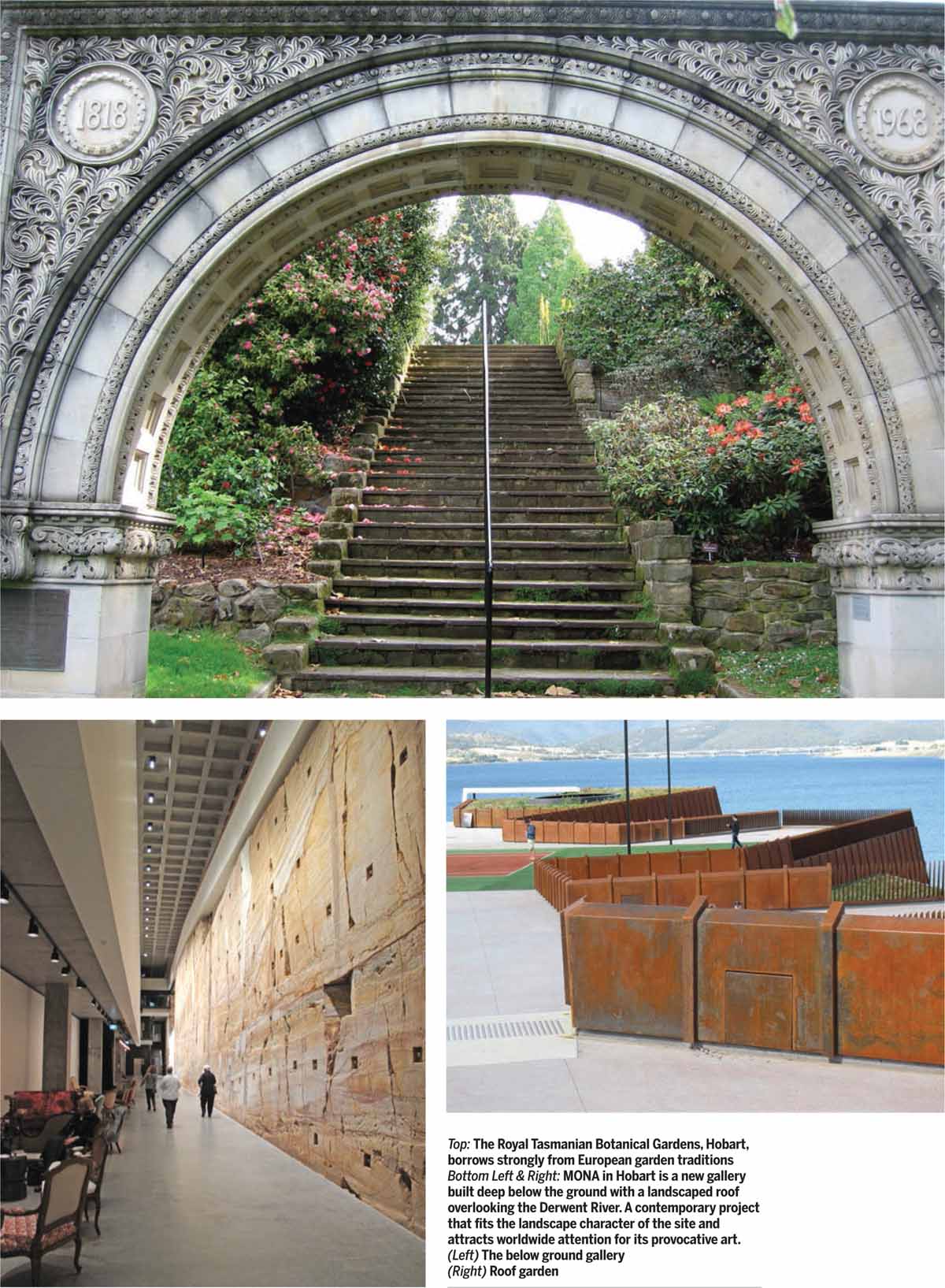

Much of early Hobart was built by convict labor and it has preserved many of its English-derived Georgian and Victorian-style buildings. As a city that has limited growth, the architecture, climate and topography give Hobart a distinctive northern European character. The recent development of a privately funded art gallery, the Museum of Old and New Art ‘MONA’, together with Tasmania’s spectacular wilderness areas, wine and food are attracting over one million visitors per year, the majority being from mainland Australia, but with growing numbers of international visitors too.

Port Douglas

Port Douglas is a town in far north Queensland established in 1877 after the discovery of gold. Gold was not a long-term prospect, leading to its present status as an extremely popular holiday destination for Australian and international visitors who wish to explore the Great Barrier Reef and the Daintree Rainforest. Its current population is around 3,500 permanent residents and it retains its share of historic buildings in the tropical Queensland style.

Planning rules that have restricted new developments to the height of a palm tree have helped this town maintain its special character.

|  |

|  |

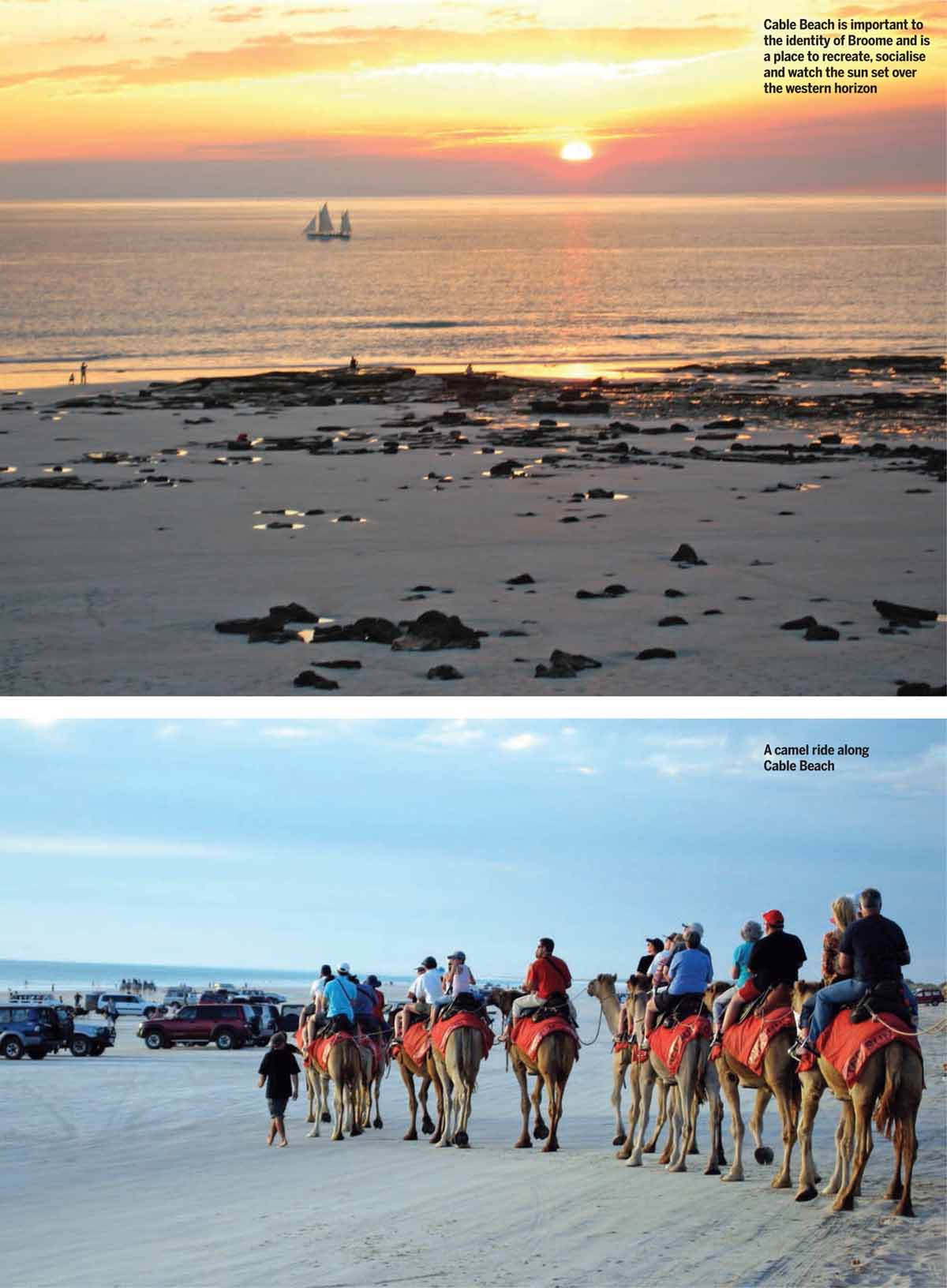

Broome

Broome sits on the north-western coast of Australia around 3000 km west from Port Douglas and 5000 km north-west from Hobart. It has a resident population of around 15,000 with over 45,000 visitors each month during the tourist season. It is a resort destination for its beaches as well as a gateway to the Kimberley region of Western Australia with its many remote outback experiences.

Broome was founded in the 1880s as a base for the cultured pearling industry that involved early collaboration with Japanese pearlers. It is also a support center for the mining industry and a center for aboriginal culture that remains strong. The Yawuru people own much of the land and water around Broome.

|  |

Echuca

Echuca is an inland river town established at a crossing point of the Murray River in 1850 and currently has a population of around 20,000 residents. By 1870 it had become Australia’s largest inland port serving to transfer agricultural produce delivered by paddle steamers along the river system to trains that in turn transported goods to the Port of Melbourne and beyond to the rest of Australia and Europe. It remains a service center for agriculture and is a tourist destination.

The character of these inland towns is primarily determined by the landscape of a flat flood plain and the landscape of river dependent agriculture and river red gum forests. They are definitely car-based, low-density settlements that have retained the heritage from earlier periods and have a generous layout of wide streets with detached houses set in gardens from most periods and styles. The Victorian period especially bestows a unique character to the residences. Like most Australian towns, car-dependent shopping malls, big box retail, motels, car sales and agricultural service activities tend to sprawl along the approach roads.

|  |

Urban character in Australia is determined by many factors

Australia is a vast country with a small population concentrated in the bigger cities including Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane where the population has flocked for the culture, employment and education they have to offer. These cities have a more complex urban form that varies from the sprawling new low-density suburban areas on the distant fringes, through inner and middle suburbs, which developed in the era of rail and trams, to higher density central areas that are fast losing their scale and heritage as new, large-scale residential and office developments are taking hold. Growth and change do vary across the country with many smaller towns and cities being less dynamic and relatively unchanged, or in decline as the decades pass.

Away from the big cities, the Australian landscape is a primary influence. Like India, Australia is a large country with widely varying topography and climate but by comparison, the influence of man is less evident because of a small population, relatively short period of European settlement and the benign nature of aboriginal society who lived in total harmony with the land for around 40,000 years before settlement.

Architecture, subdivision patterns, commercial activities and the people who inhabit cities and towns all have their part to play in determining the character of each place. Australia could do much more to protect and strengthen the character in most Australian settlements because many forces are at work in society and the world economy tends to unwittingly standardize the places where we live, work and visit.

Preserving and enhancing desired aspects of urban character is increasingly important because it adds to the authenticity of a place, which in turn contributes to liveability and identity for residents and visitors to each place.

Towns and cities that respond to local climate, topography and preserve and manage their heritage buildings and landscapes are also likely to be more sustainable and energy efficient.

Comments (0)