Research Urbanism Architecture (RUA) was co-founded in 2009 in Leuven (Belgium) by Bruno De Meulder and Kelly Shannon and Research Urbanism Architecture Landscape (RUAL) – the Los Angeles branch – was established by Shannon in 2016. RUA/ RUAL operates as a flexible urbanism research team and discovered its origins in the academic environment. It is on the lookout for new types of design research assignments and questions that deal with development conditions and contemporary issues that require innovative solutions based on solid research and intelligent design. Through experience, the team’s members focus on layered and complex urban areas where a multitude of issues including landscape, transportation, economic development, housing, conflicts in land use and climate change must be addressed simultaneously and translated into long term visions, strategic plans and detailed projects for the meaningful development of the territory.

Over the past years, RUA has been deeply involved with design research in Belgium and Vietnam. The projects presented here are a sampling of some that are at the crossroads of urban landscape analysis and design. Intensive fieldwork and interpretative mapping were key-instruments in the design research. Cartographies of hydrology and vegetation are firstly a way to read the territory and thereafter a way to re-write the landscape and script the conditions for the emergence of new realities. The evolving interplays of infrastructure, landscape and urbanism were of primary concern.

The projects present two primary design strategies. First is the strategy of water urbanisms, which learns from indigenous systems and creates new ways to work with the forces of nature via a combination of soft engineering and urban design. Water urbanism reflects on the growing challenges of water in the city, infrastructural landscapes and the re-uniting of engineered and natural processes. The predicted consequences of climate change (particularly floods), new pressures of storm water and basin management and ecological concerns create rich interdependencies of water and urbanism.

Throughout history, forests almost always formed one of the major components of the planning of the territory

The second is a strategy of forest urbanisms, which builds upon one of the built environment’s greatest legacies: the interweaving of urbanism and forests, of urban tissues and structures of plantation. Throughout history, forests almost always formed one of the major components of the planning of the territory. Forests form the counter-figure of the city (from Karlsruhe to Suzhou), embed the city (from Versailles to Moscow) and complement the city (from Paris to Dalat).

The design investigations exchange planning for flooding and planting. They create micro-topographies and robust forest structures that create space for water and robust forest structures that simultaneously generate a frame that structures urban growth, embeds the city and is resilient to climate change (sea level rise, saline intrusion, etc.). The design strategies generate varied and rich environments for everyday life structured across various scales and logics, from large-scale regions and territories (watershed and large vegetal mosaics) to the natural and man-made systems of waterways, dikes, sluices, pump stations, embankments and forests, orchards, parks, tree-lined boulevards, gardens, etc. Ultimately, the aim is to create new synergies between context-specific interdependent systems that (re)balance ecology, economy and socio-cultural values.

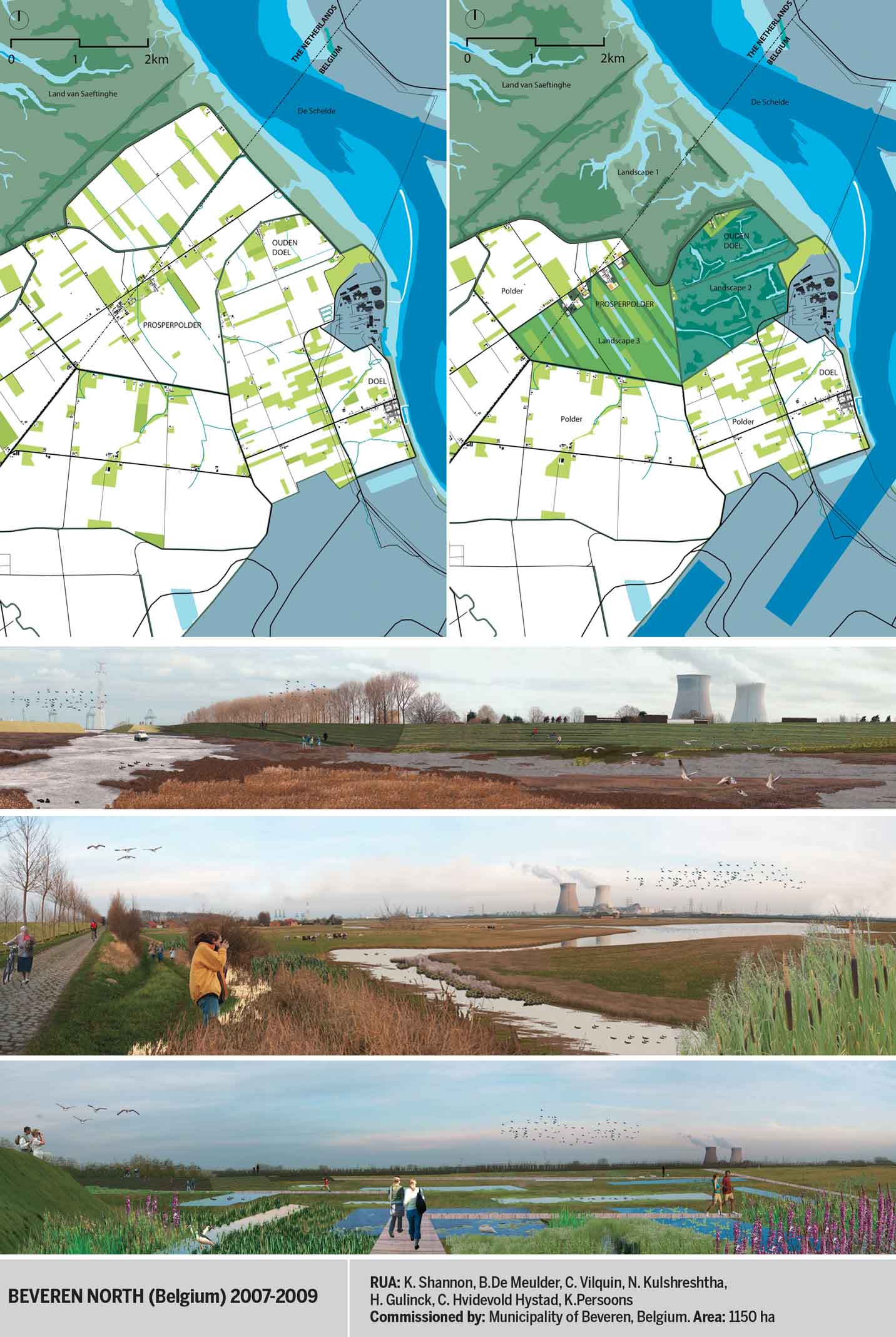

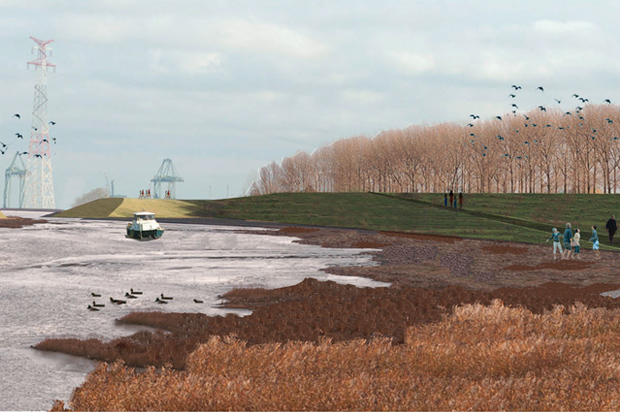

De-poldering as Nature Compensation

The Schelde River basin straddles Dutch and Belgian territories. Antwerp’s port expansion on the left bank of the river calls for ‘nature compensation’. The poldered landscape includes a productive agricultural landscape with fields and a network of agricultural domains, villages and hamlets as well as a nuclear power plant. The de-poldered landscape will comprise three water landscapes: tidal, brackish and fresh. A system of dykes creates a new hybrid territory and reconfigures the hamlets.

Trees in the City

A rich variety of existing and new forest typologies with a broad palette of tree types and plant species create a wide eco-tone, allowing for diverse atmospheres and generating new ecologies and recreational settings for Hoog Kortrijk.

Green/Blue Framework

The Hoog Kortrijk strategic plan anchors the region in a robust green/blue framework that accommodates future development. It creates a new public realm and a common platform to the existing fragmented services and isolated programmes of the area.

‘Smart’ Densification

‘Smart’ densification of the university, college, and student housing blocks generates synergies and integrates a performative public transport hub. The densification would occur along the new public infrastructure network and afforested areas. In contrast to past practices, when road infrastructure steered urban development, future development will now be canalised by the landscape structure, which is defined by afforested areas, water and tree-lined boulevards.

Urban Platforms and Landscapes

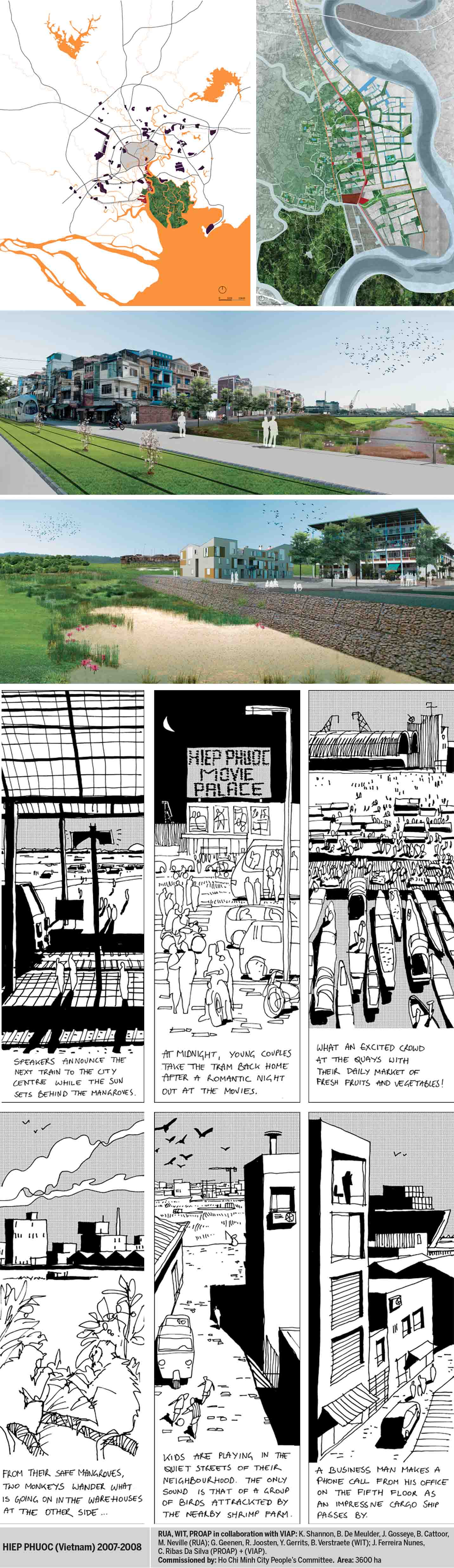

Hiep Phuoc holds a unique ecologic and economic value for the region. The proposal creates a spatially determined, strategic frame for the evolutionary growth of a state-of-the-art port and urban district. It reconciles Vietnam’s push towards modernisation while balancing the enormous ecological impact of such development. In addition to meeting requirements of relocating Ho Chi Minh City’s ports on Saigon River and developing a new impetus for socio-economic development of the city (industrial and port-related logistical services), the rise in sea level, seasonal flooding and water pollution are explicitly addressed. Highland platforms are created for urbanisation, water purification structures, the territory and port; urban and village urbanisation co-exist.

Possible Urban Worlds

The proposal carefully considers specific contexts and works simultaneously with both macro- and micro-economic and ecologic concerns and develops densities and programmes accordingly. Pragmatic locations for industry and urbanisation along the entire network of waterways are considered in light of a host of issues, including environmental protection, tourism and maintenance of the very characteristics that give Hiep Phuoc its identity – namely its green, liquid landscape.

Green-blue Armatures Framing Urbanisation

The green network comprises orchards in the south, a regional-scale Hau River hi-tech agricultural park, the recreational Cantho Linear Park, more than 50 kilometres long, and a tree-planting programme along the ‘civic spine’. Specific trees, unique to the territory, are planted according to topographical levels and soil conditions. The blue network addresses both water quantity (flooding, storm water retention, drainage and irrigation) and water quality (sewage, purification) by rigorously enforcing the cut-and-fill balance principle during the process of urbanisation. New urban development is built on platforms (various heights of fill from 2.7m upwards) embedded in the green framework and anchored on existing and new infrastructures. Rivers and canals perpendicular to the Hau River define the rhythm of open and built-up space that is always linked to infrastructures on different scale levels.

Choreographed Flooding

Fertile higher land along the Hau River, which is a result of sedimentation, is strategically embedded into the new green framework, including the ‘Hau River Park.’ This new type of park is a high-tech agricultural park that aims at realising technological innovation in agriculture and aquaculture, and is safeguarded from urbanisation by the fact that it will become a major contributor to the economy. When flooding occurs, settlements and orchards are ‘safe’, on higher land, but low paddy land temporarily accommodates water.

Variation in Continuity

The typical generous Vietnamese street profile is systematically planted with trees and incorporates storm water management, parking and a hierarchy of circulation levels. It creates complementary sets of atmospheres and microclimates –w opening invitations for all types of planned and unplanned, formal and informal public uses.

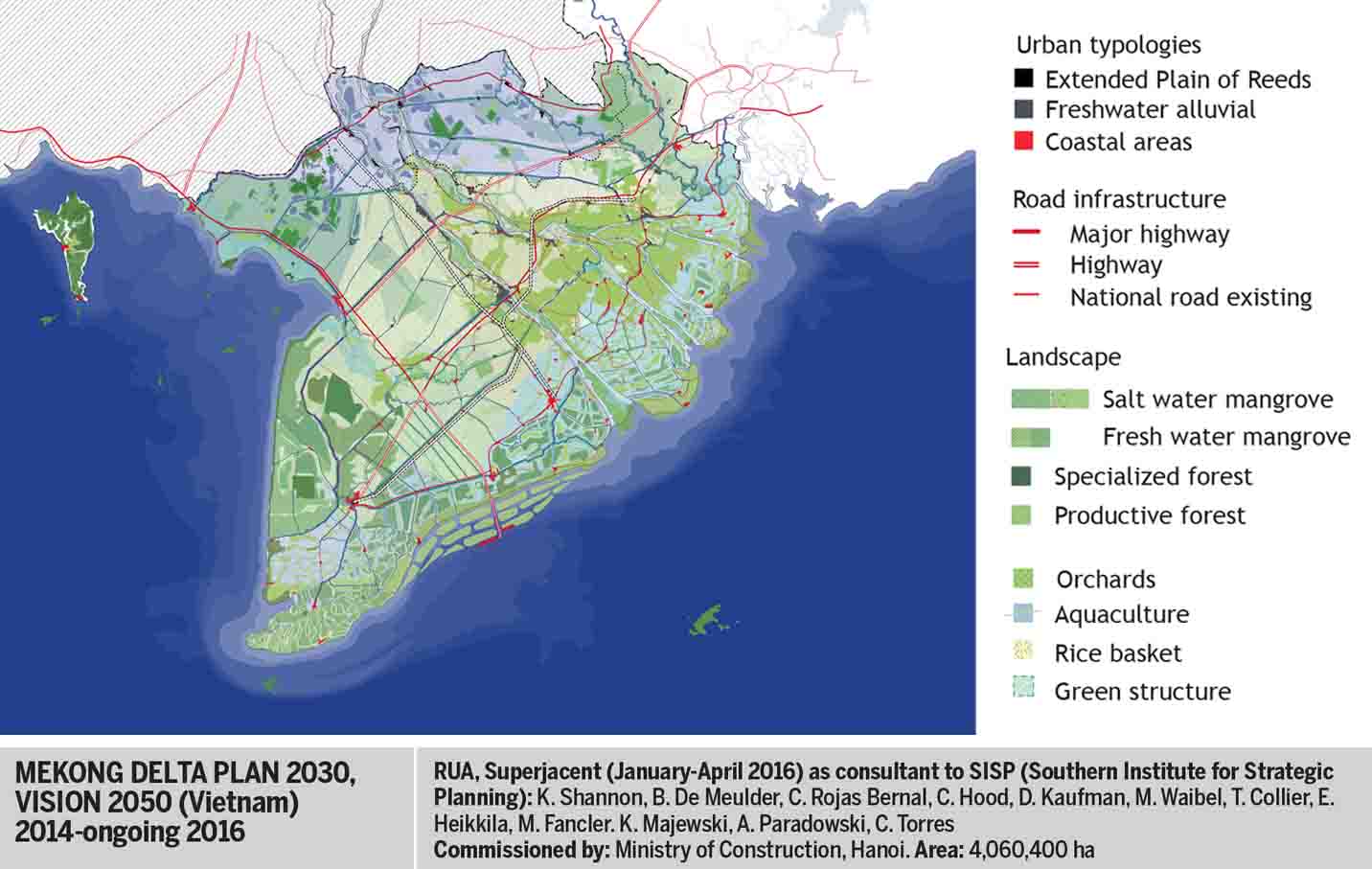

Opportunity of Climate Change and Return to the Waters

The Mekong Delta is a cultural landscape formed and transformed by its sophisticated and dynamic water management. However, the contemporary paradigm of land and water management is currently undergoing a fundamental shift that climate change will inescapably further articulate. Living with floods (in opposition to a defensive living behind dykes) and the interconnected canal system is no longer as evident. The entire hydrological regime of the Mekong River has been and continues to be re-engineered by Vietnam’s riparian neighbours. And, the delta is already bearing witness to the impacts of climate change. Sea level rise, saline intrusion, massive inundation and periods of intensive drought and rising temperatures have begun to effect the region and reveal devastating consequences on productive landscapes and settlements. The revision of the plan for the Mekong Delta Region seizes the opportunity of climate change (and the way it reconfigures the geography of the territory, as an opportunity) to realign the plan (and consequently development) with the (evolving) characteristics of the territory. The main question of the new proposed regional plan was how to organise a constructive interplay between unavoidable landscape dynamics and the social, economic and cultural dynamics of the region. The main asset of the delta (surely in view of the expected worldwide food shortage) remains its enormous agri- and aqua-cultural potential. Such a territorial identity is largely the outcome of the interplay between land and water, or more precisely: topography (including bathymetry), soil qualities (most broadly alluvia, saline and acid sulphate) and conditions, salt and fresh water parameters (volumes, qualities including carried sedimentation), and heights and extents, (tides and seasonal variations). Recognition and accentuation of the delta’s underlying geography, which has been classified into six broad agro-ecological sub-regions, can re-establish its core identity, counterbalance the relative homogeneity of the region’s urbanism and re-articulate the productive landscapes of the delta’s dynamic ecological sub-regions.

All Photos: Bruno De Meulder and Kelly Shannon

Comments (0)