The 21st century is experiencing an unprecedented challenge on mega-cities to provide equitable and affordable forms of social living. Affordability as an idea is slowly becoming a cliché with an ever-expanding inventory of gated communities and extravagant developments becoming the hallmark of every city. In the midst of global capitalist tendencies and the constant barrage of slum tourism packages, our sensibility to distinguish ‘the haves’ from ‘the have-nots’ has diminished.

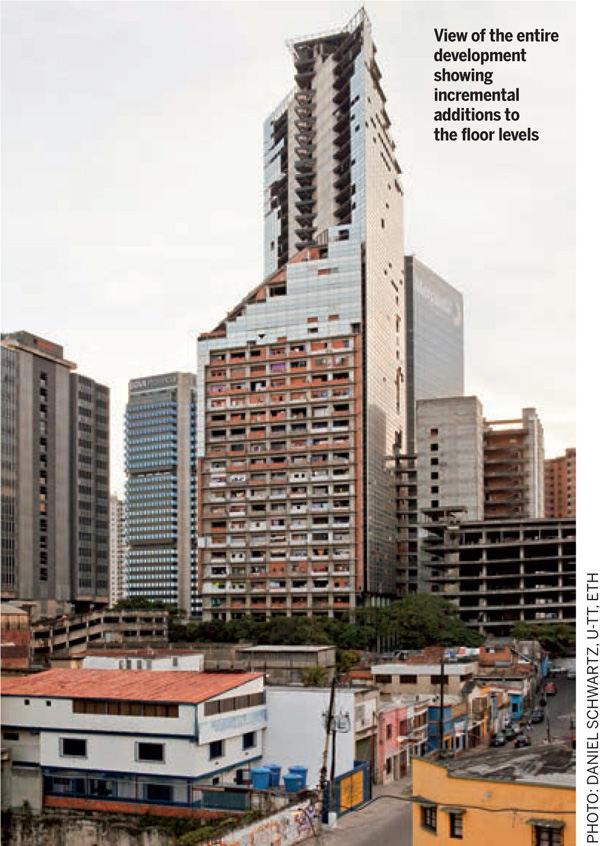

Alongside increasing adversities, the resilience for survival in the informal sector has led to new models and typologies of habitation. The occupation of Torre David in the city of Caracas, Venezuela, was one such event. It captured the world’s imagination and became a symbol of a community’s resolve to take control of circumstances, come together and, in the process, invent a new pattern of adaptability in the form of a vertical barrio (district).

We spoke to Alfredo Brillembourg, founding member of Urban Think Tank (UTT), who has spent years documenting the phenomenon of Torre David. The UTT team has performed an urban and ethnographic study, both to campaign for the validity of such an occupation as well as initiate global dialogue on lessons learnt from this exercise. Their approach posits a compelling paradigm to address the challenge of growing inequality in the Global South where they see the role of the architect as an aggressive lobbyist for affordable housing.

|  |

Amit Arya (AA) - What is the significance of the occupation and appropriation of Torre David for our contemporary urban condition?

Alfredo Brillembourg (AB) - Once we have established the fact that 50% of the world’s population is living on less than two dollars a day and that less than one percent of the world’s population controls 50% of the world’s GDP while the other 99% has control over the rest, then we can say that it is a significant amount to work with but it has to be efficiently distributed amongst the 99%. While we say that capitalism and market forces are the only way to go, we have seen that this new age of technological advancements has demonstrated a manifold increase in the unequal distribution of wealth and has further disenfranchised the lower spectrum of the world’s population from the growth of nations. Therefore, it is necessary to find a new way to create a ‘common ground’ and address the growing problem of scarcity in the world, which is a manmade fact.

The key is to incentivize the market to address the issues of bringing more equity to those who do not have adequate resources.

Torre David was one such attempt; it is a story of a fabricated scarcity; it is a symbol of the boom and the bust of a city: Caracas. It is not only a symbol of the economic capital that builds such kind of buildings but also a symbol of tragedy, the breaking of the economic market, the bankruptcy of a country, the rioting and the revolution of a disenfranchised population.

The economical breakdown of Venezuela left the tower empty for 17 years while simultaneously the country grew poorer and more people found themselves homeless.

In the city of Caracas, in a sheer moment of desperation 3,500 of them started squatting in the empty tower to escape the terrible monsoon floods. They inhabited the tower and kept moving up floor by floor as the population grew and created a cooperative in order to pay their electricity bills. Then they invited UTT inside to show them how people with their limited micro-incomes are completing the unfinished tower. So, we approached the government with the idea that Torre David could become a perfect example of a Private/Public partnership with a small amount of micro-loans to create a new model of social housing. It could be finished by bringing in an elevator company and using the existing tower as a place for installing energy efficient interventions, which would make the development a sustainable model by generating power autonomously, thus attaining a 30% off the grid status. In essence, Torre David is a significant example of taking a ruin and converting it into a model project of appropriation. The future of cities depends on our efficiency to build the new on top of the old, by reutilizing vacant buildings and underserved assets in the city to avoid sprawl and contain the existing footprint of our cities by reprogramming them in innovative ways.

Buvana Murali (BM) - Describe the affordable city of the 21st century.

AB - The fastest way out of poverty is to migrate and since the Western colonial powers had not invested enough into their former colonies you see a migration to the places of power from the Global South to the Global North. In countries like China and India there is massive migration to urban areas; if we do not anticipate and act with imagination, their cities will become hell and start looking like Caracas waiting to enter a revolution.

Sprawling cities require costly infrastructure and the appropriation of agricultural land, which is not a sustainable model.

For example, India’s proposal for ‘smart’ new cities of the future is not a good idea because I believe that the smartest city is not a technologically loaded one but a very efficient low-tech city. Dharavi is one of the smartest cities or urban villages, which generates millions of dollars in revenue each year despite its limited resources.

Though favelas and shanties are not the perfect urban conditions, they tell us how people want to live with few means and an economic push towards basic infrastructure by the government. The 21st century city is not about building the ‘perfect’ solution, because what is ‘perfect’ for society? Not what China is doing by demolishing the Hutongs and their human scale and pushing that population into fast paced, badly built 40-storey tall towers on the outskirts of Shanghai. This is a repeat of the mistakes of Pruitt-Igeo in St. Louis, Missouri. The fact is we are living in a formal and an informal city at the same time. A layer of informality will remain in our cities in the 21st century because people have found extremely resilient ways to live in cities. Rather than invent new solutions in our heads we must look at how people are living in cities today, embrace the informality and provide solutions to formalize them by way of micro-loans and infrastructural ideas. Encourage a do-it-yourself attitude like Aravena did in Chile or what UTT did in Caracas with the ‘Growing House’ project where we learnt from the Favela of Caracas and their 25-year house building cycle, where they built room after room and floor after floor. Then they started providing some schools and kindergartens for the community on the ground floors as they kept moving their houses to the upper floors.

Therefore, for the 21st century city we have to move away from the mono-functional city models. The 21st century affordable city has to be a dense pedestrian city of 1-mile radius with multiple modes of transportation and a population cap of one million inhabitants. This prototype can be multiplied as patchwork between our agricultural lands similar to what we proposed in the Parangole project.

PHOTO: U-TT

AA - You have referenced the work of Archigram, a relevant albeit utopian example created to generate an urban polemic but not to get it built. However, your work is far more contextually responsive to the urban challenges of Caracas and other similar urban conditions with a strong intent to build these ideas. How does one get such ideas built?

AB - You have to lobby Government. The architect must inhabit the public realm and must re-engage with politics. He/she should come into the city, see something existing and discover its potential rather than working on making the ‘ideal’ city. It is all about adding new layers to old cities by plugging into the existing. We think UTT is successful in that. We built the cable car project in Caracas and recently convinced the mayor of Mar del Plata in Argentina to build his new city hall in the poorest area of the city in order to valorize that piece of land.

BM - Your projects are new typologies for the problems they identify and the final manifestation usually takes the form of an economically sensitive infrastructural innovation...

AB - We only do prototypes since we see ourselves as a laboratory. Our approach has always been to identify a relevant social problem and an innovative solution; we then work with Governments to implement them. Sometimes we succeed, sometimes we don’t. For example, we are trying to do a cable car project in Kohima, India, but we do not know if we will succeed, so we propose and move on to other challenges like the ‘Empower Shack’ project in Cape Town, South Africa, where we are building solutions for the problem of low-cost housing by building 100 units in a village typology. What we try to do is invent a ‘Toolbox’ and we are aware that our first prototypes will be just as deficient as the first Walkman or the first iPhone but then there will be others who will take it forward and perfect it.

BM - You have mentioned that “in an infinitely unstable environment, architects must throw away their Ruskin - ‘when we build, let us think that we build forever’ - in favor of new goals: resilience, adaptability and transformability.”

AB - It is about embracing the unstable present and being contextual but not in a postmodern way. Referencing Frederic Jameson in whose words the context of postmodernity is a ‘fragmented heterotopia’; at UTT we acknowledge these heterotopias by building our ideas into it and by joining more pieces together in order to create new models. It is not about making money but making a good society and the architect has to take his/her role seriously because if not then there will be no mediation.

Comments (0)