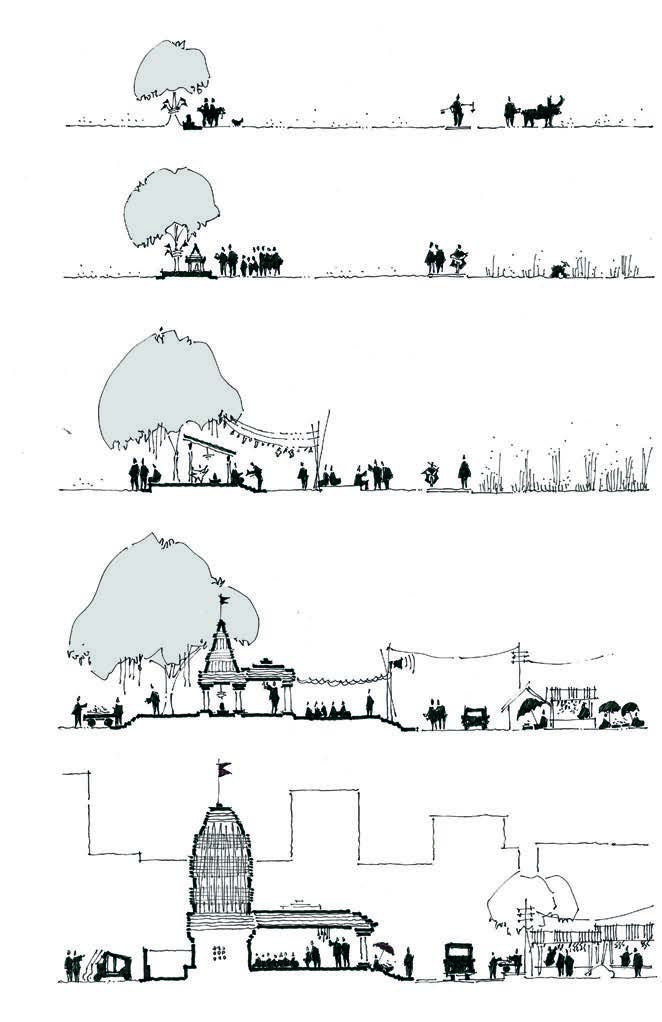

A vivid, yet often-underestimated element in contemporary Indian urbanism is the consecrated tree, that is, a wayside tree marked with insignia to pronounce its perceived sacredness within the public domain. Thousands of such consecrated trees dot the Indian commons, be it in the centre of a village or along a metropolitan street. These trees have significant bearings on the future of Indian urbanism, for many of them have been the historic epicentres of some of India’s largest temples and even entire temple towns. For instance, the Meenakshi Temple in Madurai is said to have evolved from an anonymous stone lingam (phallic symbol of Shiva) under a tree in a forest around 1600 BCE, morphing into the gigantic complex it is today, through centuries of communal worship, patronage and craftsmanship. In any Indian city, one can presently trace the ongoing metamorphosis of such shrines and temples. Beneath the branches of a consecrated tree then, is a millennial paradigm of Indian urbanism, borne through culture-specific perceptions of nature, city and place.

Perceiving Divinity: The Tree as a Deity

The notion of tree worship stems from the ancient Hindu philosophy of an omnipresent divinity; trees have been consecrated in India since primordial times. The earliest recorded depictions trace as far back as 2500 BCE, on one of the seals from the ancient city of Mohenjodaro. Through the evolution of Hinduism, certain tree species themselves have garnered the status of sacred entities endowed with mythic associations and symbolic meanings.

The peepal tree, for instance, also known as ashvattha in Sanskrit, represents the Trimurti (Hindu divine trinity), the roots being Brahma, the trunk Vishnu and the leaves Shiva. Cutting down a peepal tree is considered a sin. The banyan tree is also one of the most revered trees in India, mentioned in several sacred Hindu scriptures and invariably planted in front of temples.

Not surprisingly, many Hindu places of worship have thus begun as trees. Shading a smeared stone or a diminutive portrait of divinity, marked with thread, flags and banners, or its trunk dressed like the goddess herself, a devasthana (place of the deities) appears mysteriously under a tree’s branches, be it along the roadside or in a remote field. As the anointed abode of the gramadevata (village deity), it is worshipped through diurnal and seasonal rituals, directly under its sacred canopy. Most gramadevatas are feminine, often prefixed or suffixed with local terms for mother, sister or queen. The gramadevata of many South Indian communities is called Mari Amman and the saptamatrika (seven mothers) are believed to guard several villages throughout India, often manifested as a row of seven sacred stones under a tree. Sacred trees thus bear the spiritual weight not just of individuals, but entire communities.

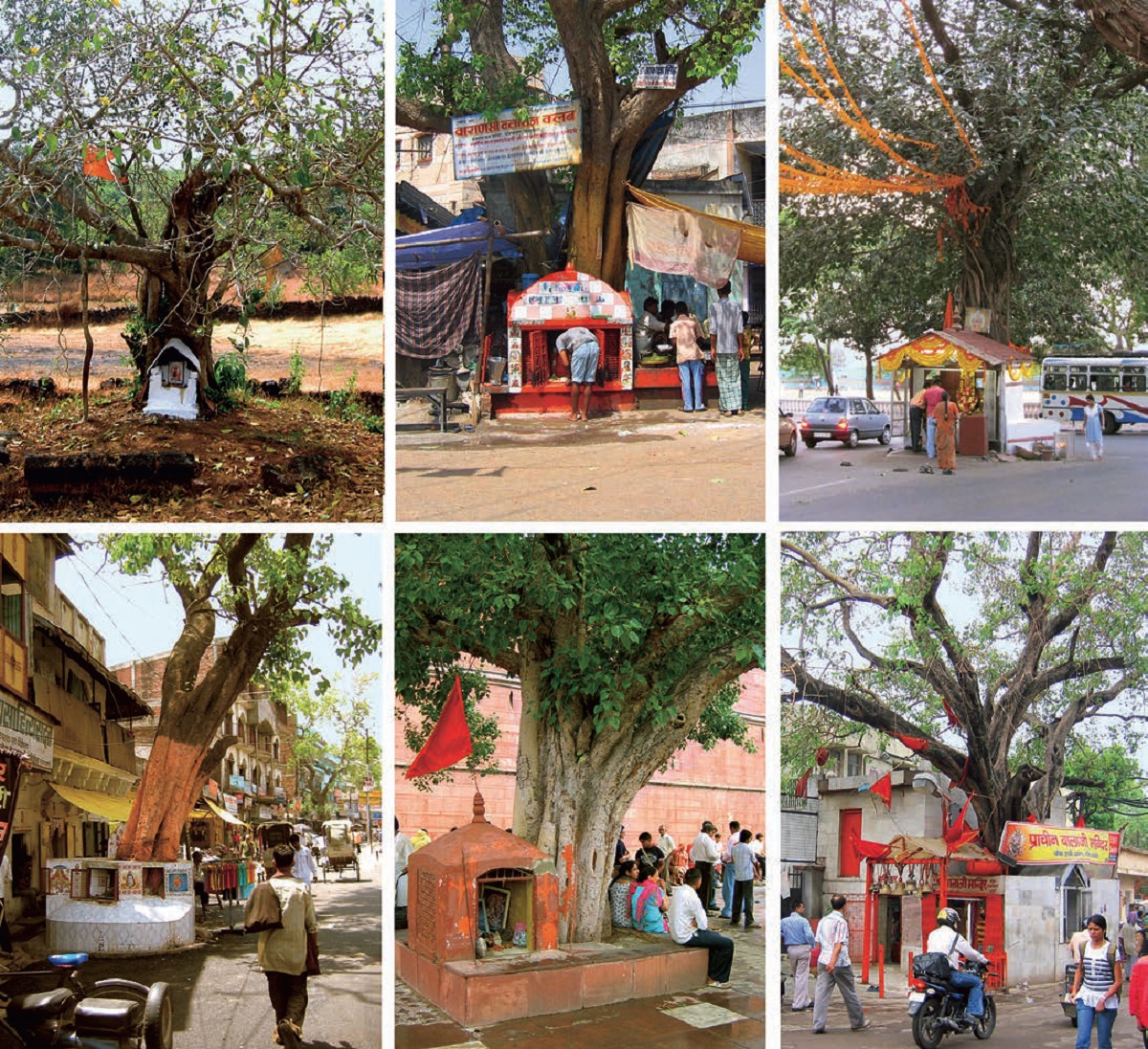

Marking Sacredness: The Wayside Shrine

When a positive change happens in the community, consecrated trees are endowed with gifts as a mark of gratitude, and their increasing eminence over time gradually elicits their transformation into shrines. This pattern is visible around urban street trees as well. In the generic Indian city, wayside shrines under sacred trees are anywhere and everywhere, shrouding all sources behind their inception. As sacred impregnations into the public realm, nurtured through silent communal consensus, they become the centres of various invisible cults. They range from the abstract to the literal, some little more than a small sheltered statuette or sacred symbol atop a platform, some with a chamber and roof, and others simply ad hoc accumulations of multiple deities in the same place. When a sacred tree dies, the spot continues to remain sacred, believed to be vibrant with the energies of the innumerable rituals of community worship.

For all their semiotic associations, such wayside tree shrines do not strictly follow the canonised symbolism of a Hindu temple. Their orientation to the cardinal directions is ad hoc, as opposed to the strict east-west alignment of formally devised temples. They face any and every way, as if no canon mattered at all. And unlike the managed, hygienic environment of city temples, most shrines are open to all people and wandering animals alike. Whether in remote villages or cities, it is this sectarian immunity that augments their presence as communal artifacts and the space surrounding these shrines gradually garners a complex social significance: it is the pradakshina patha (path of ritualistic circumambulation), as well as the setting for communal festive gatherings.

In his essay Look Out! Darshana Ahead, Ranjit Hoskote observes how the 1990s street-side shrines in Mumbai’s suburbs “follow a standard evolutionary graph: first the platform, then the parapet; in due course, an archway, this additive process culminating in the consecration of a miniature temple, rendered in grey-veined marble, complete with grille-guarded, white-tiled sanctum, bells, saffron pennant and that vital basis of the shrine’s financial model, a collection box.” There is often a predictable, formal pattern behind a wayside shrine’s evolution: They go from modest sacred spots to identifiable places with rudimentary structures and caretakers, marking the beginnings of rudimentary temples.

Birthing Place: The (Rudimentary) Temple

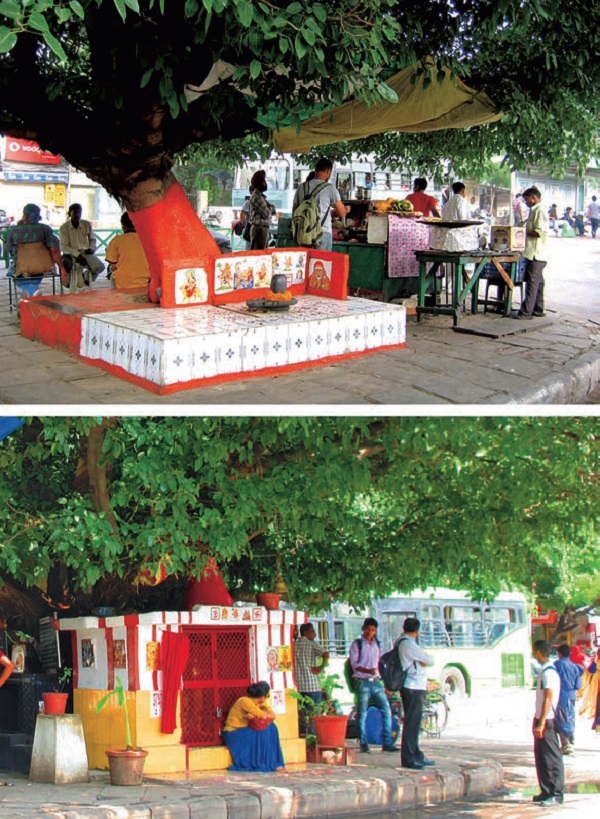

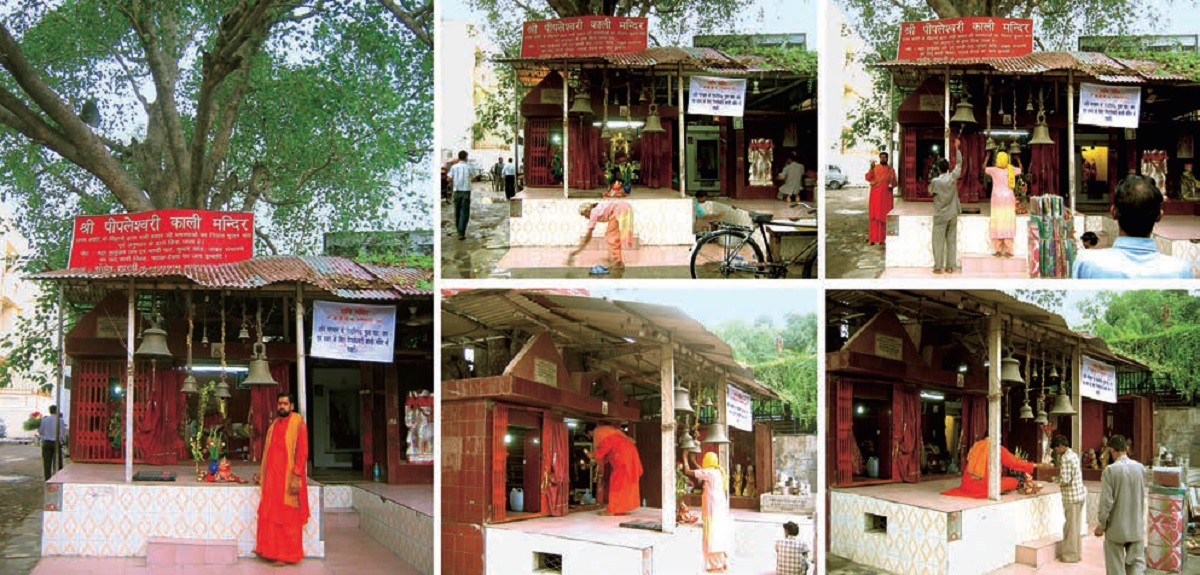

Many wayside shrines grow over time into rudimentary temples directly beneath the sacred tree. Such structures are now dominant enough to serve as identifiable urban markers and are typically endowed through communal sponsorship with minimal infrastructure such as electricity and water and an assigned priest or caretaker.

The Pipaleshwari Kali Mandir in New Delhi for instance, is located near Connaught Circus in the city’s central business district in the middle of a vacant lot beneath a mature peepul tree. With no frontage to any surrounding street, it serves as a quiet retreat behind the district’s daily wholesale flower bazaar.

Beneath the branches of the peepul tree is an arrangement of multiple statuettes and symbols atop a platform. Some deities are covered within individual mini-temples, while others remain open to the sky. On one side of the tree trunk, four adjacent shrines are unified under a shed-like structure, defining a larger temporary temple. There is a storage room for the temple’s daily apparatus and lodging the shrine’s maintenance staff. Bells hang beneath the leaves. Above the roof is a metal board bearing the shrine’s name and advertising it’s scope of religious services. In front of the shrine, a plastic tank provides water from the city mains and a circular platform encourages devotees to sit and socialise.

How did the Pipaleshwari Temple come to be? My conversations with a wandering hermit by the name of Mastanji in 2013 revealed that the peepul tree was a sacred spot since the ’70s, when he first met a Bengali devotee of Mahakali (an incarnation of the goddess Parvati) who slept under its branches. An idol of Mahakali was installed under the tree circa 1982. An idol of the goddess Durga (another incarnation of Parvati) around 1994, and two years later idols of Ram (an incarnation of Vishnu) and Hanuman (the monkey god) were installed. The shed was built in 1998. Today, the shrine has a staff of six priests and a maintenance lady, more than a hundred visitors a day and it is the local setting for important Hindu festivities.

In 2013, I recorded the early-morning activities of this place: At around six o’clock, a maintenance lady sweeps and washes the temple grounds, cleaning the raised platform fronting the sanctums. A snack vendor sets up his mobile shack at the appointed place. A barber sets up shop under one of the nearby trees. A couple of bicycle rickshaws park nearby, waiting for customers. A wandering hermit with a long white beard, black garb and staff, who has made this shrine his local destination for over 20 years, appears on his rounds. By seven in the morning, a priest dressed in saffron garb arrives and prepares the place for its daily worship rituals. An out-of-the-way urban space of only around a 1,000 square feet surrounding a tree has become a microcosm of community worship. Not too holy to serve as a dining space during festivals, or a theatre for a religious play, it typifies innumerable such hidden places within the Indian metropolis.

Top: In 2013, it was an open to sky platform with a lingam

Bottom: By late 2017, it transformed into a small, secured built structure

Many such rudimentary shrines evolve further into what can be considered the ultimate place-type born under the branches of a venerated tree: the franchised Hindu temple. Many of India’s largest temples are evidence of the continuation of Indian urbanism and the building of such monumental structures represents the spot’s maturation from anonymous beginnings to legitimate ownership. Most temples built around sacred trees reveal ingenious architectural solutions within limited spatial confines, all retaining and incorporating the original consecrated tree as an integral part of the design.

A Pattern of Indian Urbanism

The evolution of a monumental temple from a consecrated tree affirms a millennial pattern of Indian urbanism that continues to this day. What does this suggest for the future of the Indian city? Can parts of the city be understood as evolving communities around maturing holy nuclei, whose future patterns may not be entirely unpredictable? How can the ubiquity of sacred trees and their shrines be included within the conduits of Indian urban planning? On the one hand, these wayside shrines are illegal encroachments on the public domain blatantly violating zoning ordinances and by-laws, and it is not that they have always escaped their infractions. In Mumbai for instance, in October 2003, municipal authorities, undeterred by citizen protest, launched a campaign to demolish street shrines. Several illegal shrines and temples vanished leaving behind their trees or paving. But their veneration continues as sacred ruins and some have been reincarnated through the same religiosity that birthed their predecessors.

ALL PHOTOS & DRAWING: AUTHOR

Within the Indian city, the demographic associated with (but not limited to) the consecration of trees largely comprises rural migrants, slum dwellers and denizens of the pavement, that far from being a burden on the urban economy in fact supply it with a vast labour pool for the ‘unpleasant’ jobs that organised labour evades. Sacred trees embody the beliefs and convictions of these people, while also revealing their unlicensed entrepreneurship and uncanny ability to elude law and authority.

For many of these denizens, sacred trees are also analogous to the village chaupal (central village platform) that serves as a community-gathering place. This spontaneous usage of urban space can therefore be read as part of an intuitive rural wisdom with significant economic advantages.

Many of these migrants live in shacks less than five square metres, appropriating the adjoining space to eat, sleep and socialise, and shrines are an intrinsic part of this idea.

Beneath the branches of thousands of consecrated trees then, lie the seeds of a non-utopian sacred Indian urbanism, celebrating and building on everyday ordinary life. Against the backdrop of accredited city temples, we therefore cannot afford to underestimate the power of these elusive, anonymous entities. Size does not matter; what matters are the locations of these sacred dots powerful enough to bypass socio-economic legitimacy and exert powerful influences on urbanity. Today’s consecrated trees will become tomorrow’s centres and monuments. For they nurture the hopes and spiritual aspirations of the millions of underserved that are simply claiming their stake in the city. They need to be identified, accepted and celebrated as essential elements of the Indian urban landscape.

REFERENCES:

Bharne Vinayak, “Holy Metamorphosis! - The Incremental Urbanism of the Hindu Temple,” Marg, Volume 63, No. 3, March 2012

Hoskote Ranjit, “Look Out! Darshana Ahead,” The Hindu, Magazine section, January 04, 2004

ALL PHOTOS & DRAWING: AUTHOR

Comments (0)