The Maltese Islands constitute a small archipelago located in the middle of the Mediterranean basin. With a total land area of around 316 square kilometres and an estimated population of about 420,000, this island state has a population density of over 1,300 persons per sq. km. – the highest among all European Union (EU) Member States – of which nearly 95% live in urban areas. Malta has had a chequered history, being occupied by a succession of rulers ending with the British rule, from which Independence was obtained in 1964. Throughout the centuries, the foreign occupation has resulted in a rich legacy consisting of numerous historical artefacts and structures located within the different urban settlements.

Malta is currently undergoing a renewed wave of adaptive reuse strategies. This is due to a number of reasons. Most certainly, it is partly in response to existing market conditions, which in recent decades have been characterized by constant (often speculative) residential construction. This has often resulted in the demolition of traditional two-storey houses and their rebuilding into apartment blocks located on the outskirts of towns and villages. The recent building boom (particularly between 2002 – 2008) provided a strong property market resulting in an environment dominated by ‘quantity’, as opposed to ‘quality’ considerations and generating a surplus of small apartments with rooms sharing poorly lit and ventilated internal yards. In addition, the increase in prices of apartments implied that it cost as much to buy a small finished apartment within a complex of internal developments as a larger older house, albeit not necessarily centrally located and requiring some restructuring.

The reduction in quality for the newer stock of apartments and their corresponding increase in prices is pushing a number of younger couples to opt for the purchase of older houses and redeveloping them to suit their needs. In tandem with the above, the increased adaptive reuse of existing building stock has also been the direct result of government incentives and the channelling of EU Structural Funds in order to revive Urban Conservation Areas that became depleted of younger generations as they moved out to the newer edges (Figure 1). EU Funds have also been used to restore and rehabilitate a number of historical buildings, which have lent themselves to new uses. Such rehabilitation is best exemplified within the island’s capital city, Valletta (Figure 2).

Valletta and opportunities for adaptive reuse

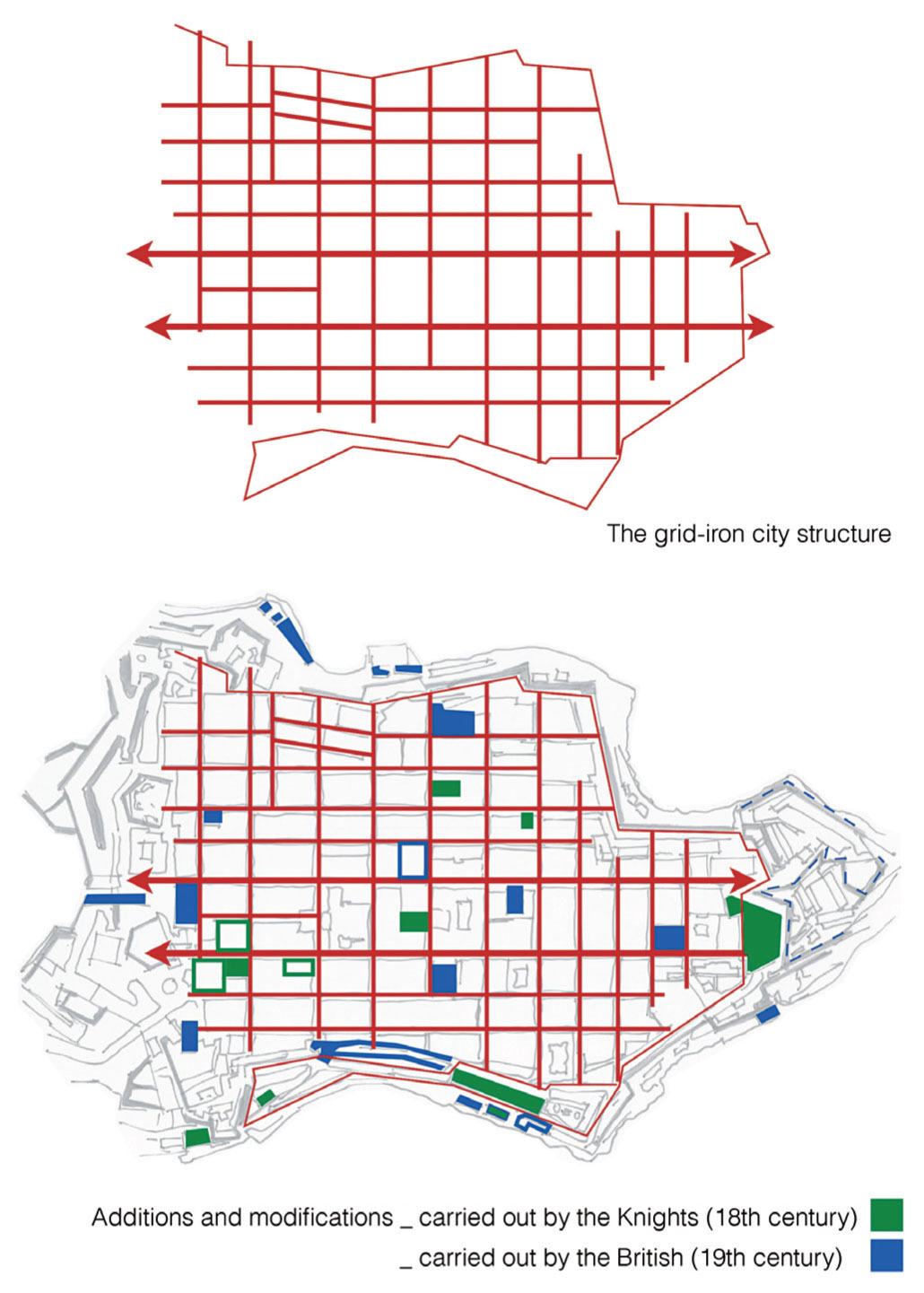

Valletta was built by the Order of the Knights of St. John on the so-called ‘Sciberras peninsula’ that lies between two harbours – Marsamxett Harbour along its north-western flank and the Grand Harbour along the south-east. It faces the urban enclave known as the Three Cities, containing the former capital of Birgu (or Vittoriosa) wherein the Great Siege of 1565 was fought and the main urban area in the first decades of the Knights’ occupation. The planning of Valletta, initiated in 1566, constituted a turning point for urban planning in Malta due to its design and grid-iron disposition as well as the building regulations that were drawn up by the Order’s housing commission in 1569.

Valletta has been designated a UNESCO Word Heritage Site, a reflection of its intricate network of fortifications and defence structures, its palaces, Auberges (the administrative centres of each of the seven Langues, or nationalities, of the Order) and stately buildings that adorn its regular street network as well as open spaces and, naturally, St. John’s Co-Cathedral (Figure 3).

Since its inception, Valletta has been a living example of adaptive reuse. Indeed, the Capital reinvented itself from a military city to a mercantile city, in the later decades of the Order’s presence in Malta. Responding to new economic demands also necessitated a rethink of the built fabric within the city structure and, although the city’s morphology and urban grain fundamentally remained untouched, new structures emerged at the water’s edge towards the later years of the Order’s presence in Malta. In turn, these were further redeveloped and altered by the British during their occupation of the Islands (Figure 4).

The City’s military defences also readapted to new warfare technologies that developed throughout the centuries, the most radical interventions being those carried out by the British during the Second World War. Post-Independence, many of the Auberges and palaces retained an important public and civic role within the city, housing important central government offices such as Ministries and Departments, as well as new cultural infrastructure in the form of museums and galleries.

More recently, large-scale interventions within the Capital have included the redevelopment of the Waterfront and the structures therein, located along Valletta’s south-eastern flank. In itself, this has been in response to the flourishing cruise liner industry, which today accounts for a significant portion of tourist influx within the Maltese shores. Other noteworthy interventions have included the offices for the Malta Stock Exchange (located within the former Garrison Chapel Building), the offices for the Bank of Valletta (located within a previous residence known as the House of Four Winds, Figure 5) and the Fortifications Interpretation Centre (within a previously derelict building extending beyond the city walls, Figures 6 and 7) – interventions that have been initiated both by the central government and the private sector.

| |

|  |

Furthermore, the central government is currently completing the restoration of Fort St. Elmo (Figure 8), located at the lower tip of the peninsula, which has been envisioned as a new cultural hub. At the other end is Renzo Piano’s new entrance to the City, a new symbol of openness that has done justice to, and restored the visual of, the abutting fortification walls (Figure 9). The integration of new pedestrian connections to the upper landscaped gardens flanking the entrance and the contemporary design for the new Parliament building, (occupying a previously informal surface car park, Figure 10) are important elements within the scheme that have redefined the status and role of City Gate today.

There have also been numerous small and medium-sized interventions consisting of the conversion of derelict buildings (or individual flatted dwellings) into residences, offices and catering establishments.

Typically, for instance, one finds a large number of law firms that have relocated to Valletta, due to its proximity to the Law Courts, although other professionals (notably architects and accountants) have also moved to the Capital. This has brought with it a number of architectural challenges, not least the constraints with the potential interventions that may be carried out on these properties due to their scheduling and/or architectural merit.

|  |

|  |

Figure 10 - (A) Old Meets New And (B) Facade Detail From The New Parliament Building By Renzo Piano Building Workshop | |

Valletta has recently won the bid to become the European Capital of Culture in 2018 (V18). This has had significant implications for the establishment of new cultural infrastructure, which will mainly manifest itself in the reuse of current buildings. Key projects in this respect include the new National Museum of Fine Arts (MUZA), which will be developed within the Auberge d’Italie (currently housing the Ministry for Tourism), the reactivation of the covered food market located in the heart of the city (Figure 11) and the conversion of the Old Civil Abattoir (the Biccerija) into a design cluster particularly focused on small- and medium-sized enterprises.

The prospect of increased tourism activity in the run-up to, during and after V18, has started to spur the development of ancillary uses, most notably the adaptive reuse of vacant buildings into guesthouses and boutique hotels. This is taking place within the city itself, within the neighbouring town of Floriana, as well as the Three Cities, which contain a relatively cheaper building stock available for sale and adaptable to reuse. The major city interventions, therefore, are becoming catalysts for other cycles of reuse.

Clearly, therefore, the city must reinvent itself once again in order to avoid the risk of ‘museumification’; that is, reducing itself to an ‘open-air museum’ that is frequented by tourists and other visitors but which otherwise fails to be relevant to its residents. The concern is important in view of the current and upcoming injection of cultural infrastructure.

Indeed, all these projects cannot happen in isolation, as fragmented, inward-looking and self-contained entities. A strategy for the city must be in place, one that sets the holistic vision and establishes the parameters within which the interventions may tie in together. In this manner, the city interventions may work together with the urban spaces within the city fabric, becoming opportunities to knit different factions of Valletta’s community together and opening up to the surrounding residential neighbourhoods.

Concluding thoughts

‘Reduce. Reuse. Recycle.’ Never before has this simple, and yet so powerful maxim, been more relevant. In the recent decades that have ensued since its inception and formal implementation through European directives, much has been done in the field of recycling, with the increased deployment of biodegradable materials and the introduction of new composite resources for the building industry using recycled materials. In focusing on the third pillar of ‘The Three Rs’, however, we might have forgotten that its underlying spirit follows a logic that commences with the reduction of energy and resource requirements and proceeds with the reuse of materials. The ‘adaptive reuse’ of existing structures, coupled with ‘sustainable rehabilitation’ practices that take into account the energy performance requirements that we have come to expect of modern buildings today, best encapsulate the above logic.

At the same time, as exemplified by Valletta’s account, the reuse of buildings must be accompanied by the restructuring of other city elements, particularly the unbuilt spaces (Figure 12).

Only in this manner may urban interventions spark off wider regeneration processes and instigate effective, positive change for its citizens. This is the ‘unseen’ benefit of reuse, the intangible impact on the city’s ‘socio-spatial’ fabric and the ‘added value’ that may be given back to local communities.

FIGURE 1/2/3/10B/11/12: KRIS MICALLEF, WWW.KRISMICALLEF.COM/ FIGURE 4: DR ANTOINE ZAMMIT, FIGURE 5: ALEX ATTARD & MANUEL CIANTAR, FIGURE 6/7: FORTIFICATIONS INTERPRETATION CENTRE, VALLETTA, FIGURE 8: DEMICOLI & ASSOCIATES, FIGURE 9/ 10A: ANNAMARIA ATTARD MONTALTO

Comments (0)