Although the city, as a human creation, did not originate as a technological artifact, its evolution through urban history could arguably be attributed more than anything else to the evolution of technology. The most paradigmatic shifts in the size, form and experience of the city, stem largely from advances in technology and machines, as well as the methods used to create them. A number of dimensions surface in this dialogue: how technology has transformed the physical city, that is, its anatomy and tangible aspects; how technology has transformed the everyday experience of the city, that is, its social and cultural activities; or how technology has redefined urban identity and regional boundaries. Then there is the relationship of technology to aspects like food, urban health, political power and public policy. Plus there is the city itself as a trigger for technological growth. The relationship of technology and the city is a complex subject, and one of the most compelling ways to understand how far we have come as settlers on this planet and how much we have transformed our urban lives.

From Villages to Empires

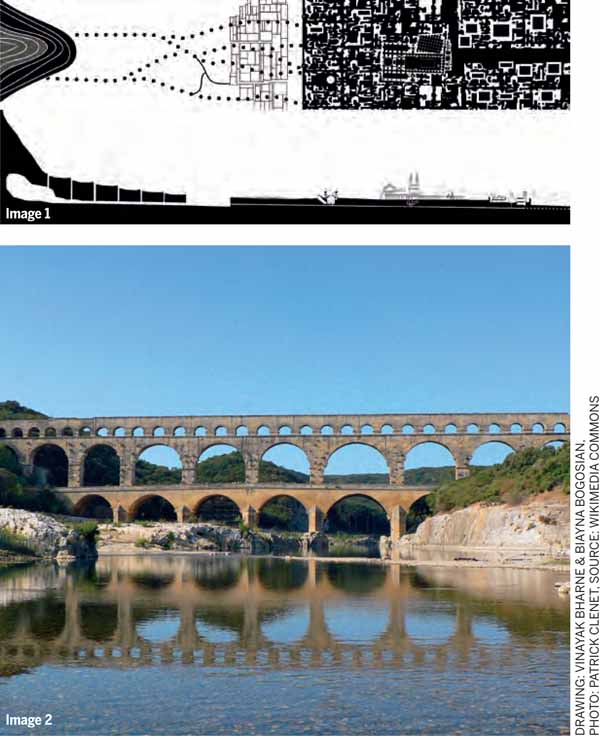

Image 2: Pont du Gard, an ancient Roman aqueduct bridge that crosses the Gardon River, from which it takes its name, built in the 1st century CE

In the old world, some of the most ambitious technologically-driven urban projects were related more than anything else to that fundamental sustaining force – water. One thinks of the sophisticated drainage system of Mohenjodaro (2600 BCE, Pakistan) or the qanats (subterranean water channels) of Achaemenid Arabia (550 – 331 BCE), but it is in Rome’s aqueducts that ancient hydro-infrastructure reached a new visual scale (Image 1, 2).

Circa 315 BCE, after Rome’s demand for water had long exceeded its local supplies, the first aqueduct, the Aqua Appia, was commissioned by Appius Claudius Caecus. It ran for 16.4 kilometres, remaining underground before entering the city and dropped 10 metres over its length to discharge approximately 75,500 cubic metres of water every day into the Forum Boarium.

Even as the Aqua Appia was being constructed, another major urban project was under way in Rome: The Appian Way (circa 312 BCE). This was the first major road built specifically to transport troops between Rome and Capua. Mobility infrastructure in the old world was not just about human locomotion and trade but something far more ambitious – warfare. And with this came a dramatic geographic shift: modest compact villages and towns surrounded by agriculture were now inter-connected by regional means of transport that taken together marked the boundaries not of kingdoms, but empires – be it Rome, Egypt or Persia.

There is then an intricate historic relationship between technology, conquest and the physical growth and spread of cities. The entire history of colonisation could be attributed to this notion. It was in 1499 CE that the Portuguese ship San Raphael dropped anchor within sight of a verdant palmfringed coast called Goa, marking the beginning of 400 years of European colonial rule in Asia, embodied in hundreds of new towns and cities in a foreign land. This collision – or confluence – of two formerly disparate worlds occurred due to the advanced naval technology of the European powers and their possession of that powdered propellant – Gunpowder.

Gunpowder or Black Powder had a significant influence on the evolution of the European city. With the introduction of siege artillery, by the 16th century cities had physically changed with a new kind of defensive fortification. The massive defensive walls of the ancient Roman or Babylonian city were replaced by low walls and bastions, further protected from infantry attack by wet or dry moats (Image 3). But gunpowder was also used in massive civil engineering efforts, such as the 1681 construction of the 240-kilometre Canal du Midi in Southern France, linking the Mediterranean Sea with the Atlantic Ocean. Even as late as 1857, it was used extensively in railway construction, such as the 12.9 km long Mont Cenis Tunnel in the European Alps.

Such advances in the West owed their presence to the Chinese. They had invented gunpowder during the Tang Dynasty (9th century CE) and it had reached Europe on the Silk Road along with another equally important Chinese contribution: By 1300 CE they had adapted the technology of printing on cloth to paper under the influence of Buddhism. By the 1500s, 50 years after the invention of movable mechanical printing technology by German printer Johannes Gutenberg, printing presses were in operation throughout Europe. The era of mass communication and books had begun and this would permanently alter the structure of society – and by extension the cultural and intellectual life of the city.

The Factory, the Suburb and the Skyscraper

Manchester’s (Great Britain) population in 1685 was about 6000 people. By 1760, it was 40,000. By 1801, it had exceeded 70,000 and by 1851 it was around 303,000. Such dramatic changes in urban density were catalysed by three things: the steam-powered factory that lured work-force concentrations; the railroad transportation system; and the commercial production of theautomobile in Europe and the United States. Circa 1900, with the advent of the industrial-age, gone were the dirt roads and camel caravans of the old world.

The idea of Zoning originated as a direct response to this rise of industrialisation. The goal was to separate noxious uses like slaughterhouses and steel plants from places where people lived. With affected residents unable to bring lawsuits against these industries, city reformers saw the need for a new way to protect them.

From its inception, 20th century zoning represented the antithesis of traditional urbanism: It was all about separating uses within the city; it was illegal to have offices and apartments above retail stores or corner shops within residential neighbourhoods.

This new regulation was not aimed at creating healthy or walkable cities; it just separated ‘incompatible’ uses while setting the maximum ‘envelope’ within which to build on a lot.

Image 5: Los Angeles, California – aerial view looking towards the skyline of its historic Downtown. Note the vast horizontal carpet of single family homes arranged on a grid

PHOTO: IMAGE 4-NGERDA,IMAGE 5- TUXYSO, SOURCE: WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The evolution of zoning paralleled a love affair with the automobile, particularly in the United States. The enacting of the 1956 Federal-Aid Highway Act authorised the construction of 66,000 km of highways over a 10-year period. In Los Angeles, that boasted one of the most extensive train networks in the world, 1,000-odd miles of rail were dismantled and by circa 1963 overlaid by an extensive freeway system (Image 4). Three decades after the 1940 inauguration one of the nation’s first freeways – the Pasadena Parkway – the words ‘smog,’ ‘gridlock’ and ‘sprawl’ were being increasingly uttered in many American cities (Image 5).

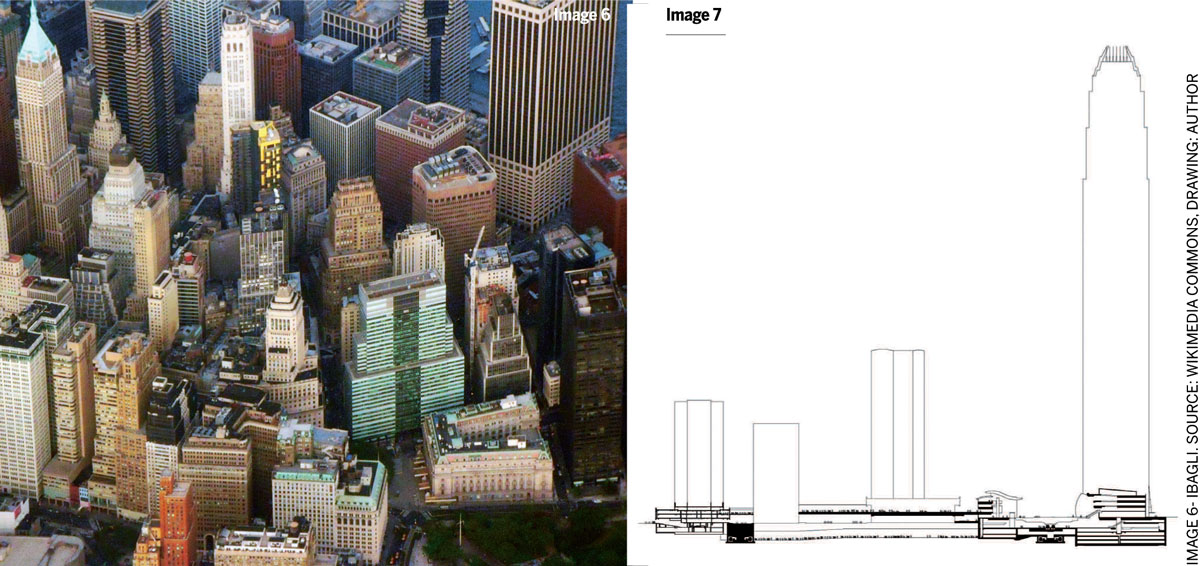

Image 7: Diagrammatic representation of Hong Kong underground

As a physical form, the traditional city saw dramatic shifts: Its structure changed from poly-centric to uni-centric, with the car connecting several exclusively residential suburbs to a central business district. The seduction of the single family suburb instigated its rampant proliferation, eating up the countryside. Meanwhile, the high-rise city had already emerged, with steel and the elevator now redefining density as well as urban scale: In Manhattan, New York, the Chrysler Building, an Art Deco skyscraper, stood at 1,046 feet as the world’s tallest building for 11 months before it was surpassed by the Empire State Building in 1931 (Image 6). And the urban underground too was emerging as parallel world (Image 7). By the 1970s, beneath Toronto surface streets was a growing labyrinth of shopping tunnels and retail nodes serving thousands of people every day.

When it comes to size however, the most impressive building accomplishment of the machine age is the Panama Canal, one of the largest civil engineering projects in human history (Image 8). Hundreds of steam shovels, dredges and power drills excavated Panama’s narrow isthmus to physically connect the Pacific and Atlantic oceans. The canal was constructed with a lock system to raise and lower ships from a large reservoir 85 ft above sea level. By opening and closing enormous gates and valves, water from the reservoir would refill the locks by gravity. The canal opened on August 15, 1914, a decade after the two American brothers Orville and Wilbur Wright had built the world’s first successful airplane. By the 1950s, the Panama Canal, and the first widely successful commercial jet, the Boeing 707, now connected cities at a scale and pace the world had never seen before. The airport was not just a symbol of advanced human travel but unprecedented trade, just as the sea port was not just a symbol of trade but the very economic power of cities and entire nations.

Urbanity in a ‘Flat World’

In 2005, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Thomas Friedman wrote a groundbreaking book titled The World Is Flat. It was an examination of the changing world at the dawn of the 21st century through globalisation and the emergence of information technology - the first commercial installation of the fiber-optic cable in 1977, the first IBM PC hitting the markets in 1981, the first version of the Windows operating system being shipped in 1985 and the founding of the money transfer system PayPal in 1998. Friedman noted that just like the freeways in the 1950s had flattened the United States, breaking down regional boundaries and easing the movement of people and goods, so had “the laying of global fiber highways flattened the developed world.”

Not unlike how industrial technology had generated before, this new era of invisible technology spawned its own urban entities.

On the one hand, places like the infamous Silicon Valley emerged in the San Francisco Bay Area in the United States, the ‘silicon’ terminology originally referring to the region’s large number of silicon chip innovators and manufacturers. On the other, just as the car-wash was emblematic of the machine-age, the internet café was its digital-age equivalent, an urban offspring of a new era of globalised banking, the worldwide web and the growing ease of global travel (Image 9). This ever-increasing velocity of transportation, capital and communication has now transformed even the role of something as fundamental as food as the organising node of regional and national identity.

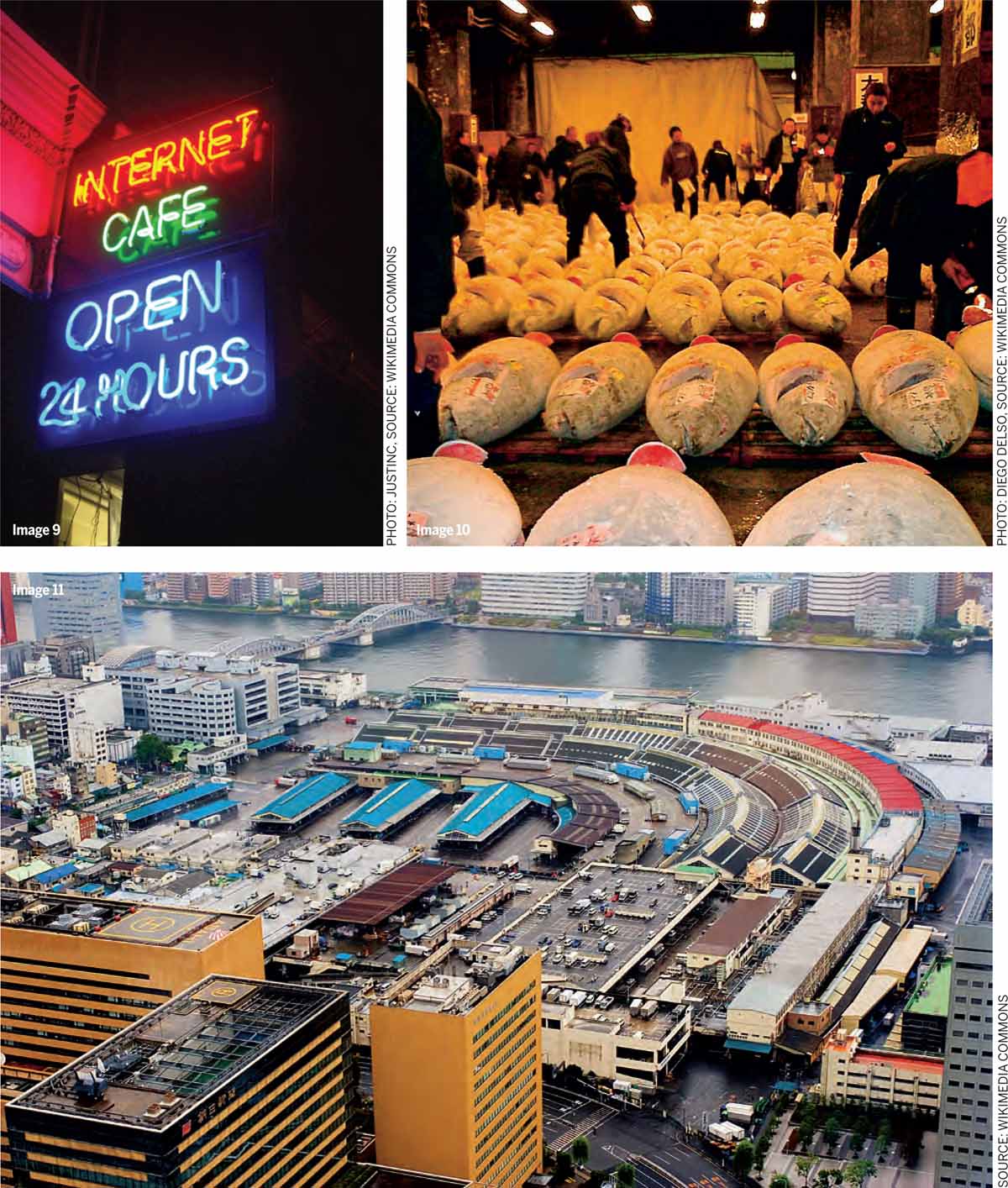

Image 10: Tsukiji Market, Tokyo - interior

Image 11 : Tsukiji Market, Tokyo - aerial view

For instance, the Tsukiji Market is one of the three seafood markets of Tokyo, located between the Sumida River and the now famous Ginza shopping district (Image 10, 11). It deals with some 450 different kinds of seafood going from cheap seaweed to giant Tuna. But Tsukiji is not just a local or national market. It is from here that thousands of tons of seafood are frozen, cut, packed and flown to every corner of the world. It is from here that lines lead to and from almost anywhere, bringing with them trends and trajectories of Japan’s economic growth and the increasing globalisation of the seafood trade. Tsukiji is the heart of a global phenomenon called sushi. Thanks to airline travel, tuna for global sushi is now being farmed as far as Australia and happily appears from New York to Warsaw. Similar results have occurred in other fields: In Aalsmeer (Netherlands) for example, flowers from the world over are sold in auctions to be flown to other destinations around the earth (Image 12).

We now live in a time where local institutions are shaping and spanning global urban and ecological processes. From McDonalds to Gap, globalisation and information technology are changing not just the city but the very destiny of the planet.

The Sustainable and Smart City

Even as concerns of climate change triggered the notion of the “Sustainable City,” the increasing access to digital technology surfaced that of the “Smart City.” Part of what unifies them is an effort to use advanced technology to enhance urban wellbeing – in transport, energy, health-care, water, waste, etc. – whilst reducing resource and energy consumption through simultaneous performance monitoring (Image 13). Numerous projects in both developed and less-developed societies are revealing the promise of this new technology-city relationship.

In Sweden, more than 99 per cent of all household waste is being recycled today using advanced technology and monitoring systems, compared to the 38 per cent recycled four decades ago. Recycling stations by law are within 300 metres from a residential area. Most residents separate all recyclable waste in their homes and deposit it in special containers within their block, or drop it off at a recycling station. Newspapers are turned into paper mass, plastic containers become plastic raw material, food is composted into soil or biogas that run rubbish trucks, wasted water is purified to be potable, and smoke from incineration plants consists of 99.9 per cent non-toxic carbon dioxide and water, further filtered with the sludge from the dirty filter water used to refill abandoned mines.

However, that Smart City thinking is not necessarily about being high-tech, but rather about efficiently driving sustainable economic growth and better citizen life and is being increasingly recognised across the less-developed world. For example, in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), after mudslides wreaked havoc in April 2010, the city’s mayor decided to set up the Rio Operations Center (COR), with the help of technology giant IBM. The centre coordinates more than 30 municipal agencies, using satellites, cameras and GPS systems to gather real-time information on traffic, weather, electricity use etc., and uses this information to manage transport flow with the help of computerised traffic lights, rerouting cars around accidents and congested areas.

Elsewhere in Stellenbosch (South Africa), the Stellenbosch Innovation District, in collaboration with the local university, has built smart shacks, using alternative energy and mobile technology to address the needs of its residents. The shacks are made from easy to assemble fireproof material that produce off-grid energy through roof-mounted solar panels. One buys electricity through mobile phones, with batteries charged in the day and used at night inside the shack to charge the cellphones. In other words high-technology is being engaged as a transformative agency in less developed regions and this is both hopeful and optimistic.

In Prospect

The evolutionary nexus of technology and the city then surfaces at least three separate trends. First, the limitation of the historic city, in that its physical and economic growth was only as big as the local ingenuity of its available technologies. Second, the ambitions of the industrial city, instigated by massive transportation advances and mass production. And third, the concern of the post-industrial city that is now seeking to amalgamate digital technology back with traditional ideas of sustainability. This concern stems from the recognition that each technological advance while giving the city new progressive dimensions has come with its own price. It is the technologically advanced city that has polluted the air, changed climate, destroyed rivers and forests and introduced over 60,000 synthetic chemicals into the environment causing the greatest rate of species extinction in the last 65 million years.

As such, while it seems convincing to embrace the potential of smart technology towards sustainable cities, it is important to remember that sustainable cities are not only about clean or smart technologies but also about their efficient structuring.

From the aqueduct to global sushi, technology has no doubt been one of the key forces behind our urban evolution, but at the end of the day, it is the decisions and choices we make, singularly and collectively, as city dwellers and city shapers, that will determine our urban destiny. Reflecting on how technology has transformed our urban lives must therefore be understood less as a glorification of our accomplishments and more as an opportunity to rethink the premises, ambitions and dogmas upon which our cities have been built.

Comments (0)