“Any city gets what it admires, will pay for, and, ultimately, deserves... And we will probably be judged not by the monuments we build but by those we have destroyed.” - Ada Louis Huxtable

It’s been a year since the global pandemic has ravaged New York City calling to question the very notions of public space. Commuting in crowded trains is hardly a thought on people’s minds right now. Yet, defying all odds, the city saw the opening of Moynihan Station, a 45,000 sq.m. space for a new train hall that reused an underutilised beaux arts post office. At the opening ceremony, the Governor of New York State said: “Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan was a man of true vision. He saw the potential in an underutilised post office and knew that if done correctly, this facility could not only give New York the transit hub it has long deserved, but serve as a monument to the public itself. As dark as 2020 has been, this new hall will bring the light, literally and figuratively, for everyone who visits this great city.”

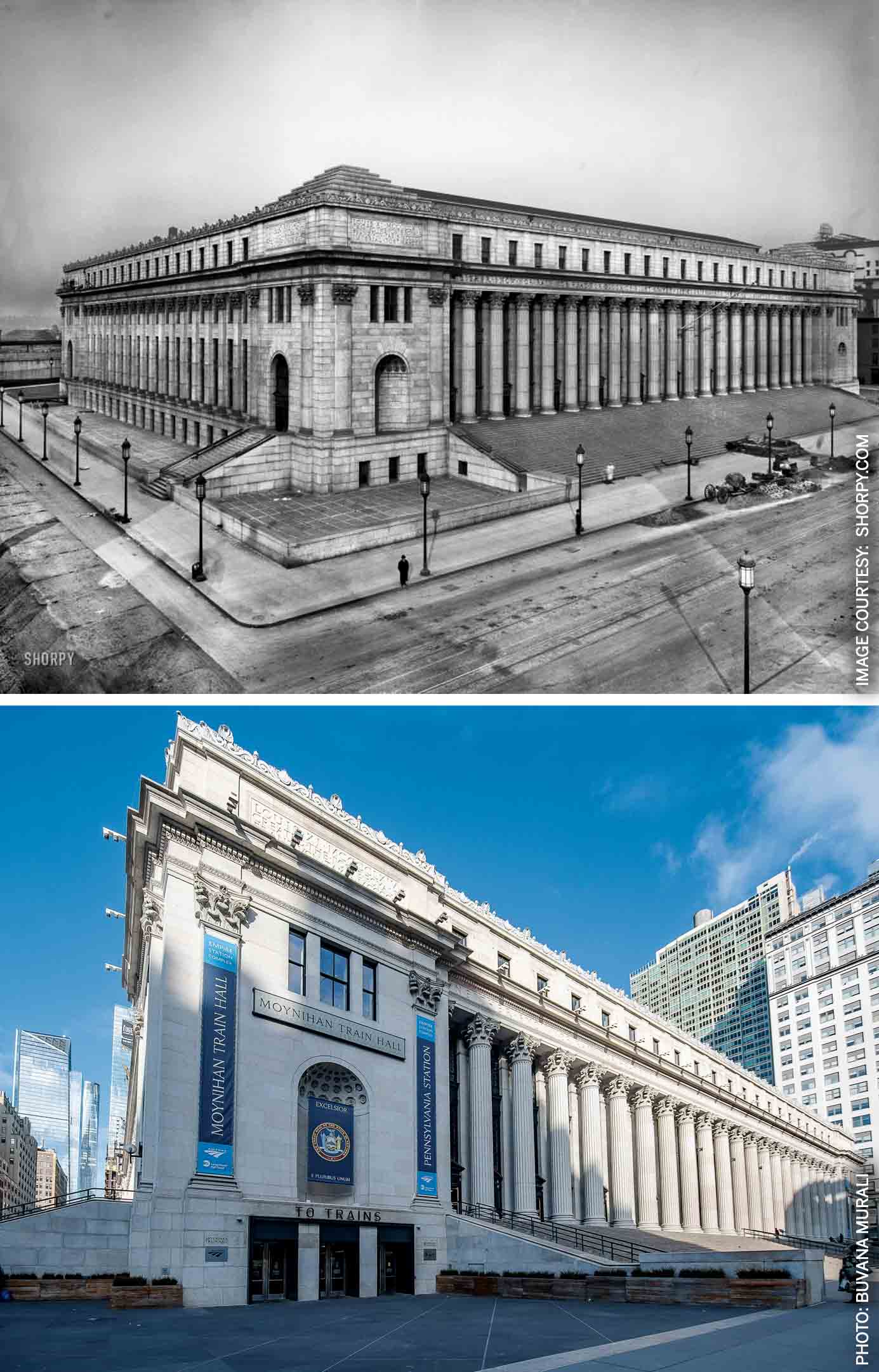

Bottom: The Farley Post Office building opened in January 2021 as the new Moynihan Train Hall

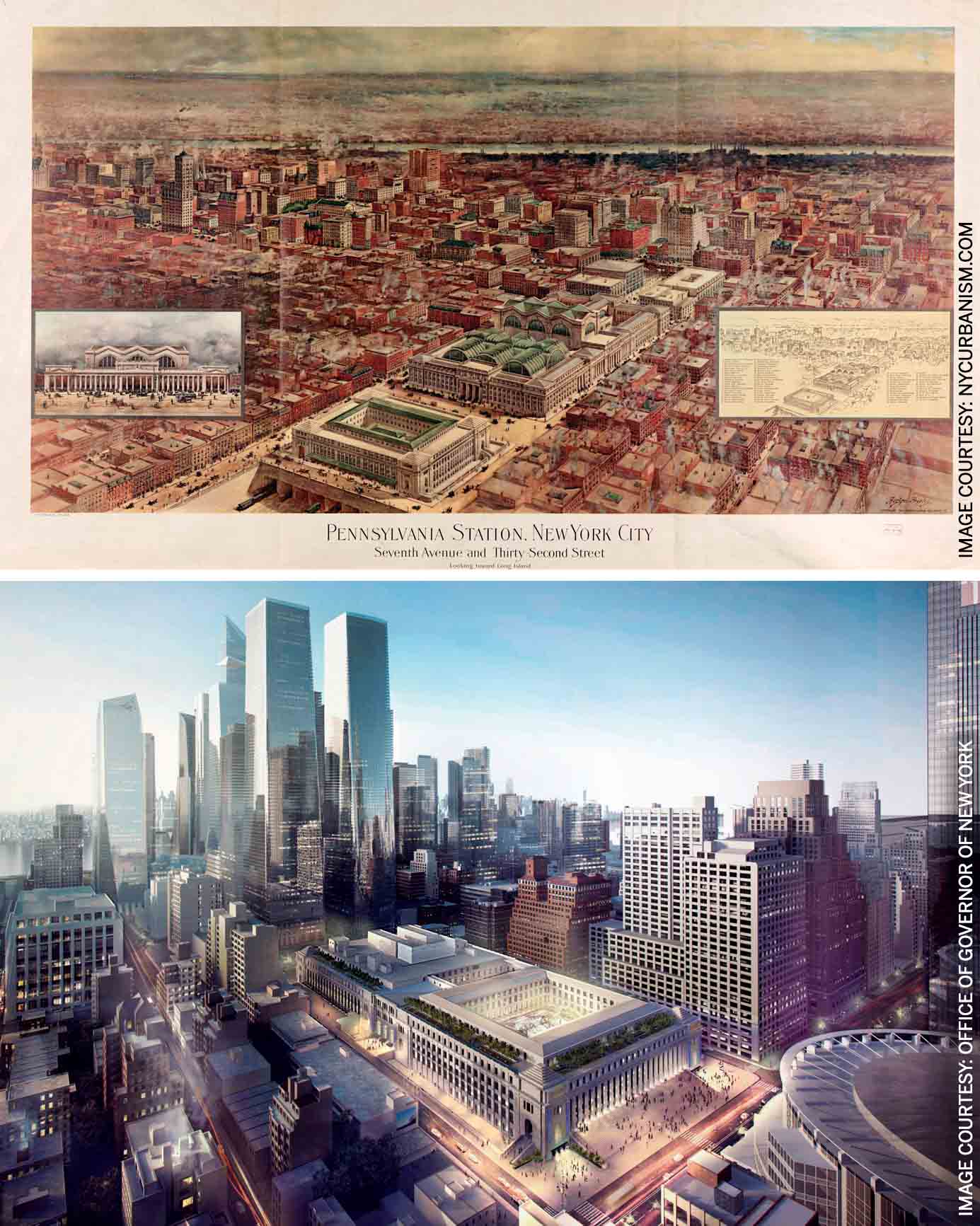

Bottom: Aerial rendering of the transformed post office into Moynihan Train Hall showing the courtyard as a light-filled concourse space

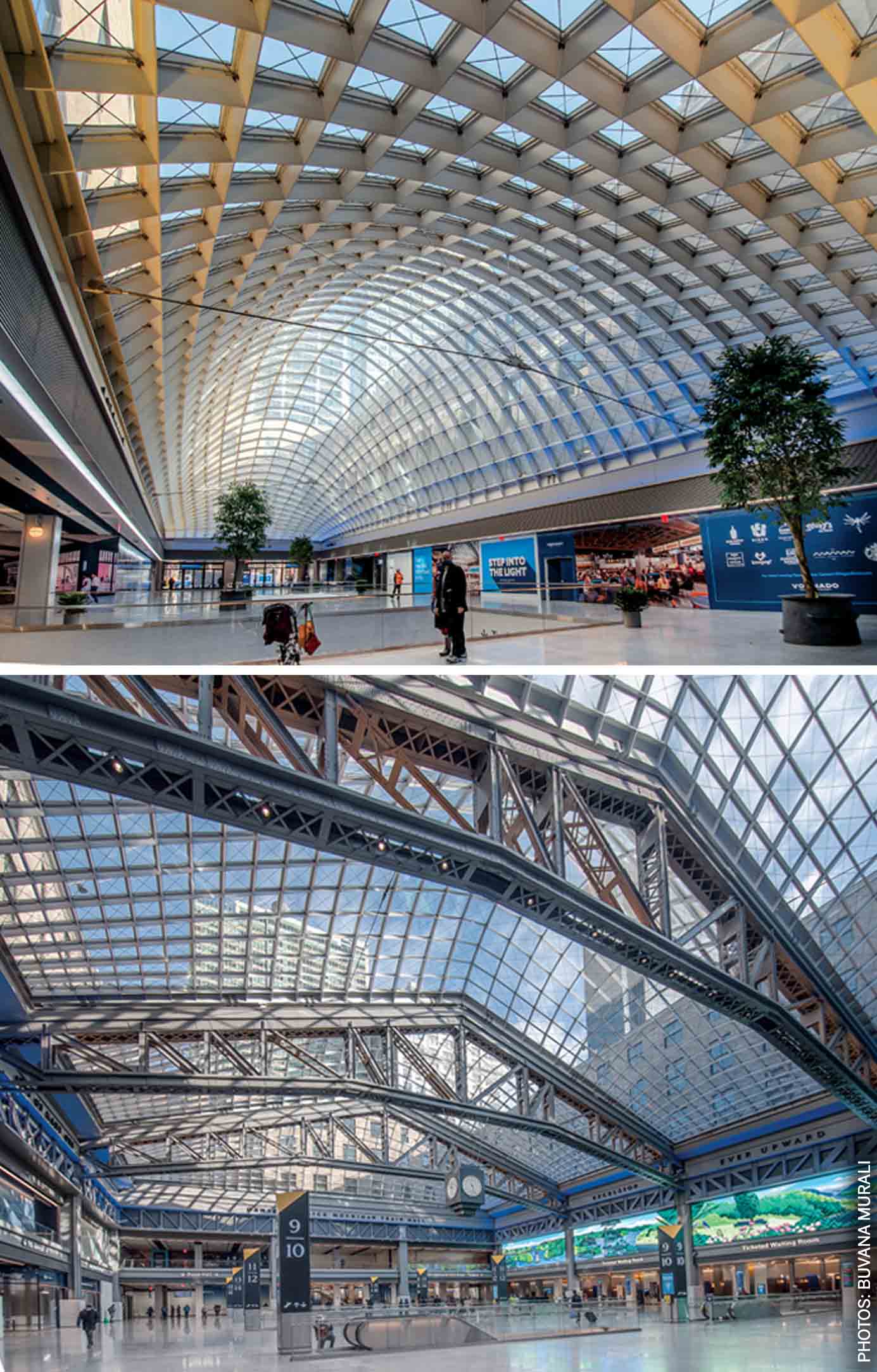

And light it does bring, through the one-acre large glass barrel vaults hovering 30 metres above what was once the mail sorting room of the James Farley Post Office; the second largest building in New York City at the time of its construction. The new Moynihan Train Hall, an exemplary study in adaptive reuse, provides the much-needed respite from the warrens of Penn Station. For decades, Penn Station’s 700,000 commuters were desperately underserved by its three-metre-high artificially lit tunnels and accompanying chaos, as they navigated their way up from its underground concourse levels to New York streets. Penn Station is one of the busiest train stations in the world and accommodates more passengers than LaGuardia, John F. Kennedy and Newark International Airports combined, in a space that is de facto the basement of Madison Square Garden. For the past 60 years, since the demolition and consequent redevelopment of the erstwhile monumental train hall into a sports arena, arriving in the city has been the complete anticlimax of the gateway it deserves. The new Moynihan Train Hall, in recalling the vaulted concourse of the original Penn Station, manages to restore a semblance of its grand civic gesture. The 30-metres high skylight that holds an acre of glass is held by three of the building’s original steel trusses with an intricate lattice framework, soaring above the concourse and bathing passengers in natural light.

It is the result of a public-private partnership 30 years in the making, surviving numerous governments and schemes to get it going, and finally breaking ground five years ago. This station is also emblematic of all the reparations to right the wrong committed by the demolition of the beaux arts beauty of Penn Station. In return for that action, the city gained a historic preservation movement that saved thousands of landmark buildings including the James Farley Post Office, which is now the Moynihan Train Hall.

Penn Station is one of the busiest train stations in the world and accommodates more passengers than LaGuardia, John F. Kennedy and Newark International Airports combined

Crossing the Hudson River to Manhattan

The histories of Moynihan Station and its original ‘twin’ Penn Station across the street are inextricably linked and talking of one is incomplete without mentioning the other. It is a tale of tunneling across the Hudson and East Rivers to bring inland trains into Manhattan and creating a gateway deemed worthy of New York City. This 16-acre patch of land along the western edge of Manhattan, between 7th and 9th Avenues, bears witness to many of New York’s historical events, including the rise of the railways, its fall with the coming of affordable automobile and air travel, the birth of a preservationist movement, the death of the post office as an institution and the rehabilitation of the building as a station for the next era of public transportation.

Until the early 20th century, trains coming from the United States hinterland terminated on the western edge of the Hudson River in New Jersey from where ferries completed the final stretch of arrival to Manhattan. Pennsylvania Rail Road (PRR) – one of the biggest railroad companies – saw an incredible opportunity to tunnel through the Hudson River and converge into an ‘immense passenger station’ in Manhattan. The vision was to bring trains from the inland areas in the west and from Long Island further east. Inspired by the striking marriage of art and industry in the Gare d’Orsay in Paris, PRR president Alexander Cassatt charged the architects McKim, Mead and White to envision a space that would celebrate “the entrance to one of the great metropolitan cities of the world.” The architects turned to the imperial scale of public buildings in Ancient Rome, ‘and were guided by a vision of civic grandeur, translating the mundane business of boarding trains into a stately procession, and subsuming the commotion of constant movement and disorganised crowds into the stations’ overriding order.1

When it opened in 1910, Penn Station was the largest train station in the world and the 4th largest building. The terminal was immense; its central waiting room was the size of a football field and 50-metre-tall arched glass and steel trusses soared above the hall and the city’s largest indoor public space. Its 15-metre-wide grand stairs almost spanned an entire city block. Its capacity grew from 200,000 passengers when it began to almost 100 million passengers at its peak in 1945. Not only did these tunnels and the station open up New York to the rest of the US, it also opened up the city to the suburbs. Within 10 years of operation, 2/3rd of its passengers were suburban commuters.

This was also a time when mail was transported by rail and post offices and train stations were collocated. PRR mooted the idea to build a post office building of comparable scale across the avenue as an architectural bookend to McKim, Mead & White’s gloried station. When built in 1912, the James Farley Building – then the terminal post office – occupied two full city blocks and matched the grandeur and scale of Penn Station across the avenue. It was designed by the same architects responsible for Penn Station, in whose vision, two edifices read as part of one large ‘civic complex’. The building was a veritable labyrinth, straddling several of the tracks that served Penn Station. Chutes, conveyor belts and elevators from the post office delivered mail directly to the underground station platforms. These century-old links positioned the post office almost perfectly for its use as Moynihan Train Hall.

Redevelopment of Penn station: An act of vandalism

By 1945, train ridership had peaked and close to 100 million passengers a year walked through Penn Station’s doors. After the war, rail travel began to decline. The hard-to-maintain behemoth fell into major disrepair and was soon covered in grime and advertisements. In the 1960s, faced with the future of imminent bankruptcy, the PRR took the most economically-driven decision and sold their air-rights, allowing for the demolition of the main building and train shed, to make room for a new entertainment arena: Madison Square Garden. This decision kept the underground infrastructure and platforms intact and decapitated the ‘non-functional aesthetical’ portions of the building – its soaring ceilings, grand foyers and above-ground halls. The station’s mezzanines were downsized and moved underground in rooms ‘bereft of light

or character.’ 2

The loss of the monument to what was perceived as progress, catalysed the architectural preservationist movement in the United States

Amongst the uproar that followed the demolition, several voices were from modern architects and urbanists of the time including Jane Jacobs, Philip Johnson and Robert Venturi, who called it “…. a monumental act of vandalism…” The loss of the monument to what was perceived as progress, catalysed the architectural preservationist movement in the United States and a watershed New York Landmarks Law was passed. Since its creation, the law has helped save Penn Station’s sister terminal, Grand Central and 30,000 other historic buildings around the city from destruction.3

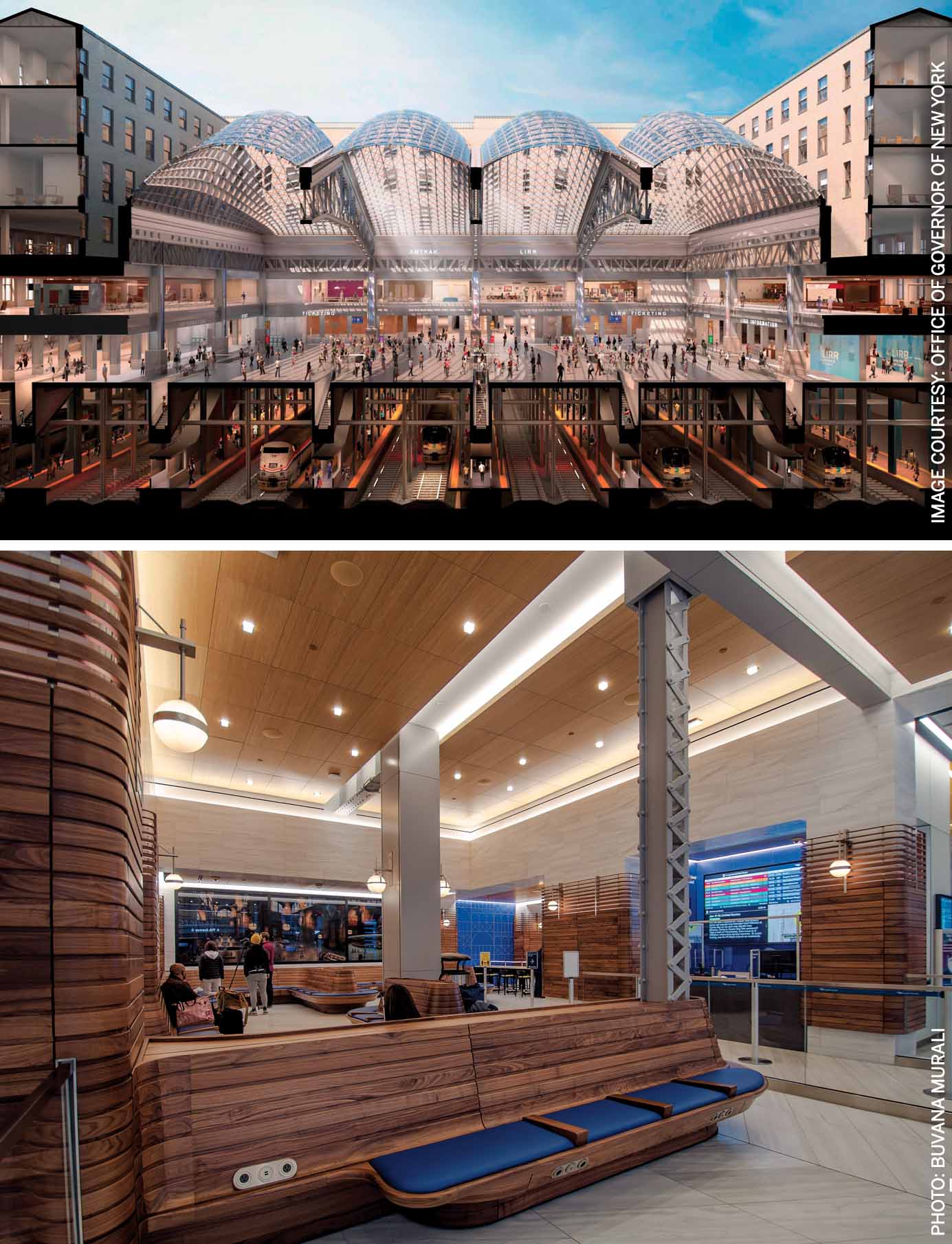

Bottom: A new gateway to the city: The conversion of the old mail sorting room into a light filled concourse. The design retains three existing steel trusses and adds a newly engineered vaulted glass roof that allows daylight to fill passenger spaces and create a contemporary public space

A new opportunity from reviving the old

By the early 1990s, the post office building was severely underutilised and started moving its operations to another facility. The idea of repurposing it as a train hall was first floated nearly 30 years ago by Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a senator for New York. Designed to the same grandeur and scale, Farley’s mail-sorting facility, with its access to railway platforms under Eighth Avenue, could potentially restore, if not fully return, the lost icon. The complicated infrastructural proposal passed through various attempts, architects and bureaucrats for years until finally, in 2016, the architecture firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, which had been working on various conversion schemes since the 1990s was awarded the job.4 In five years, an army of design consultants weathered all including a global pandemic to deliver a station that is reminiscent of the old Penn Station. The design preserves three existing trusses infilled with a modern lattice layering the hall’s history and industrial quality with a contemporary expression.

By no means does the Moynihan Train Hall expand the capacity of the original Penn Station. It is simply an extension of a handful of its platforms, the remainder of which are still dependent on Penn Station across the street. As spectacular as it is as a train hall, Moynihan will only serve about 5 to 15 per cent of Penn Station’s ridership. Before the pandemic, some 700,000 people used underground tunnels daily, three times the number it was built to handle. If as many as one million or more want to use it in the coming years, the project will need more tracks and platforms and new tunnels under the Hudson River. The economy of the Eastern Seaboard depends on it and on increasing Penn Station’s capacity.

Bottom: The new passenger waiting areas that recast the post office’s legacy in modern materials and language

A step in the right direction

The new hall is a necessary first step in addressing much of the transportation issues and the blight of the existing Penn Station. The project has been decades in the making and is a testimony to the city’s resilience and commitment to civic space. Not only has it survived multiple recessions and administrations, it has continued construction activity through the pandemic. At the peak of the pandemic, when people were sounding the death knell of the city, Facebook signed one of New York City’s largest commercial leases in the Farley Building, providing a much-needed booster to NY real estate.

Ada Louise Huxtable is right: our built environment is a reflection of its inhabitants and what they value and a city is the result of our shared values, collective decision making and our willingness to fight for what we deserve. In Moynihan Hall, by elevating the human experience and creating a gateway worthy of New York, the city certainly got what it deserved.

References:

- Conquering Gotham: Building Penn Station and Its Tunnels, Jill Jonnes, Penguin Books

- https://www.nytimes.com/2007/11/02/opinion/02fri3.html

- https://behindthescenes.nyhistory.org/penn-station-masterpiece/

- https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/11/arts/design/moynihan-train-hall-review.html

- https://www.nationalreview.com/2018/10/rebuild-penn-station-and-rectify-a-crime-against-architecture/

- https://www.myleszhang.org/2020/07/09/penn-station/

Comments (0)