As hubs of economic activities, cities drive a majority of the world’s energy use. Energy is essential for urban development, transportation, industry, commercial establishments, buildings, infrastructure, utility services and food production. A World Urbanization Prospects study by the UN estimates that though cities constitute only two percent of the earth’s surface they are home to over 54% of the world’s population. People migrate to live in urban areas for improved quality of life, better job opportunities and other social advantages. The same report suggests that by 2050, two-thirds of the world’s population will live in urban areas, with the greatest growth in China, India and Nigeria.

The way in which cities expand and operate plays a major role in their energy demand. In 2013, globally, urban areas accounted for the majority of primary energy use amounting to 64%. Energy use varies depending on the spatial form of the city, availability of public transport, location and type of economic centres, climatic conditions and lifestyle and mindset of people. The first three factors determine the energy consumption required for transportation and the latter two factors determine the energy load for buildings.

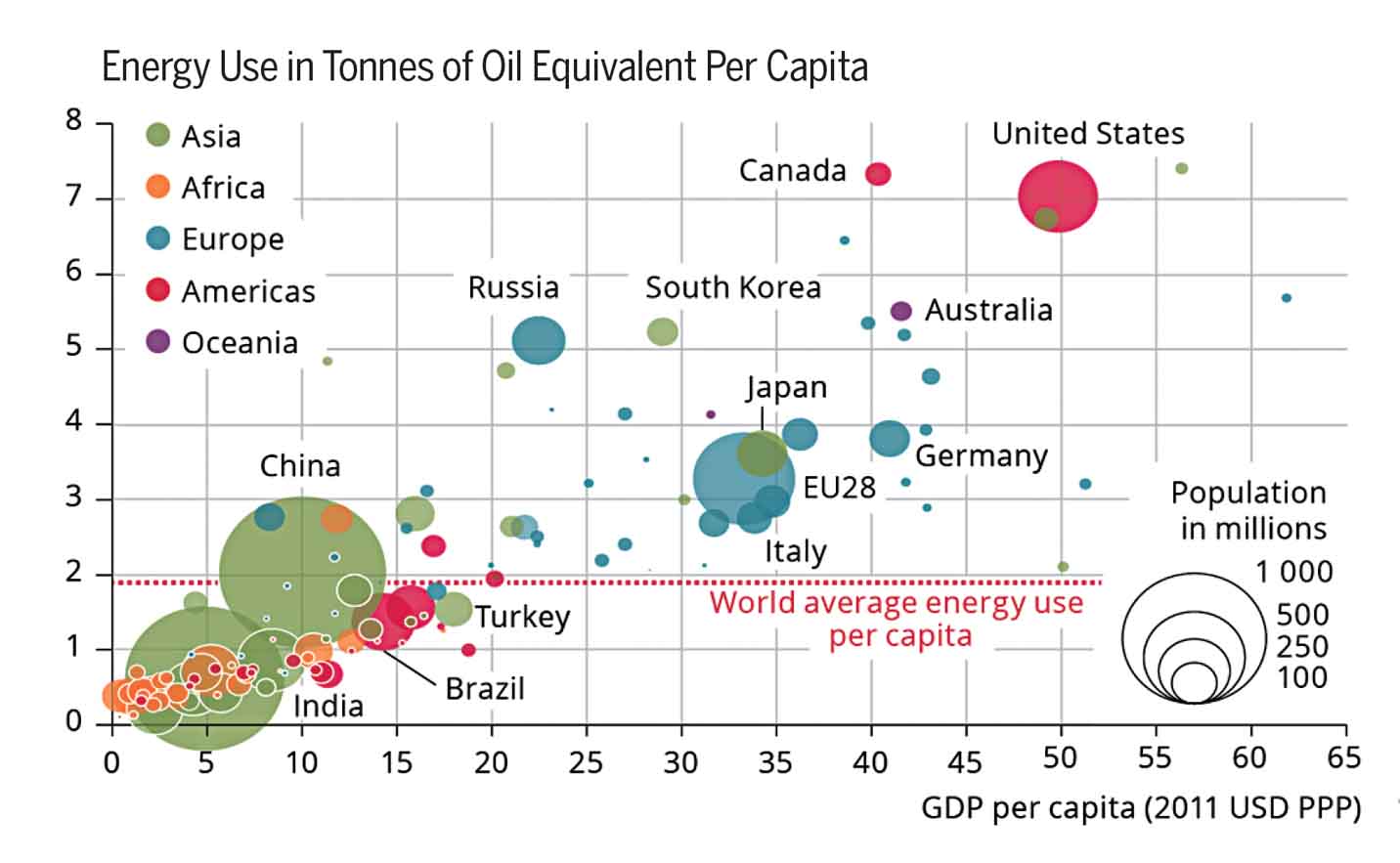

The interlinkage between energy consumption and economic growth of a city is a complex vicious circle. Gaining access to electricity and other energy sources will provide an initial increase in Gross Domestic Product (GDP), but having a higher GDP will in turn drive higher energy consumption. A chart based on the World Bank Indicators below, presents the 2014 data of per capita energy consumption versus per capita GDP. The trend is significant: the higher the country’s per capita income, the more energy it consumes.

Source: World Bank Development Indicators |

The world economy is expected to double over the next 20 years and this increase would lead to increase in energy consumption. In advanced economies, the existing urban form of buildings, infrastructure and industries tend to ‘lock-in’ energy consumption patterns and available sources of power. These economies will continue to remain energy intensive due to ownership arrangements, associated employment and economic activities, manufacturing units, along with lack of governmental initiatives for a complete energy overhaul. However, this trend will change in the future as many economies are transitioning from the manufacturing sector to more service-based industries. Further, in fast emerging economies such as China and India, an improved energy mix with renewable energy and better energy management practices will help realise a more productive and energy-efficient economic output.

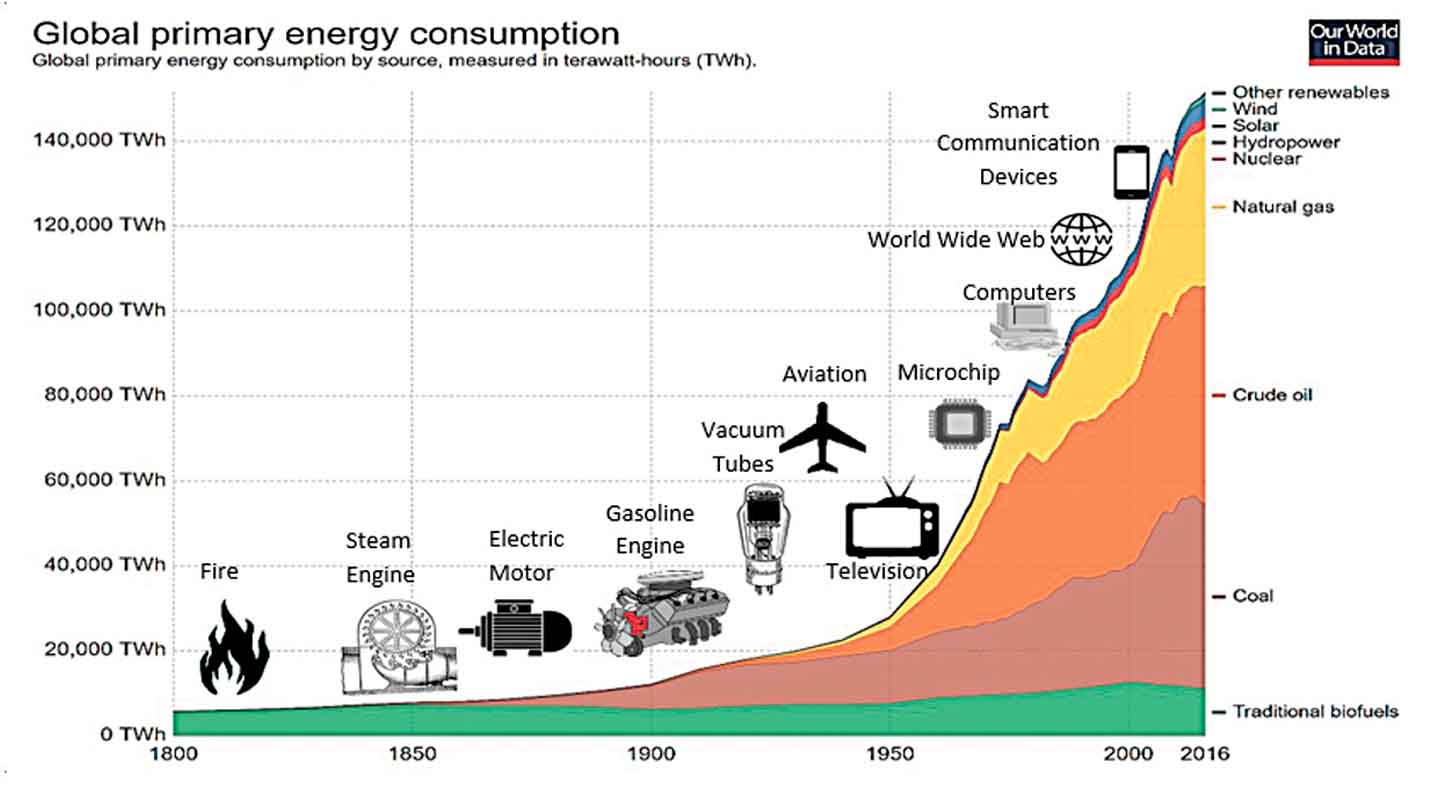

History of global energy production and its sources

It would be essential to understand how energy production has evolved both in terms of sources of generation and the quantity of production.

Historically, the needs of people were very simple comprising largely of space heating and cooking. This energy was produced by burning wood or organic matter. In the 1850s, with the invention of the steam engine, wood and traditional biomass were replaced with a more efficient and less expensive resource: coal. The substitution of wood with coal was the premise of the Industrial Revolution. Then came oil, where the consumption grew exponentially with the introduction of ships, road vehicles and then airplanes.

The mid 1900s witnessed the advent of natural gas and hydroelectricity. The coal consumption had also increased significantly with its use, to generate electricity in power plants, in industries for smelting iron into steel and for heating buildings. Power lines extended for miles between cities with the changing lifestyle of people. Low cost automobiles made suburbs possible, increasing the urban sprawl. The use of energy grew quickly in every sphere of day-to-day activities, literally doubling every decade, primarily due to leap-frog improvements in technologies and decrease in cost of energy production.

By the mid-20th century, the energy mix had diversified significantly. Coal overtook traditional biofuels and oil was up to around 20 per cent. By 1960, the world had moved into nuclear electricity production and extensive use of natural gas. The renewables of the modern day appeared from the 1980s, but the penetration of renewable power had been low initially due to high capital investment, intermittency and low power generation outputs.

The use of energy grew quickly in every sphere of day-to-day activities, literally doubling every decade

Recent energy consumption patterns

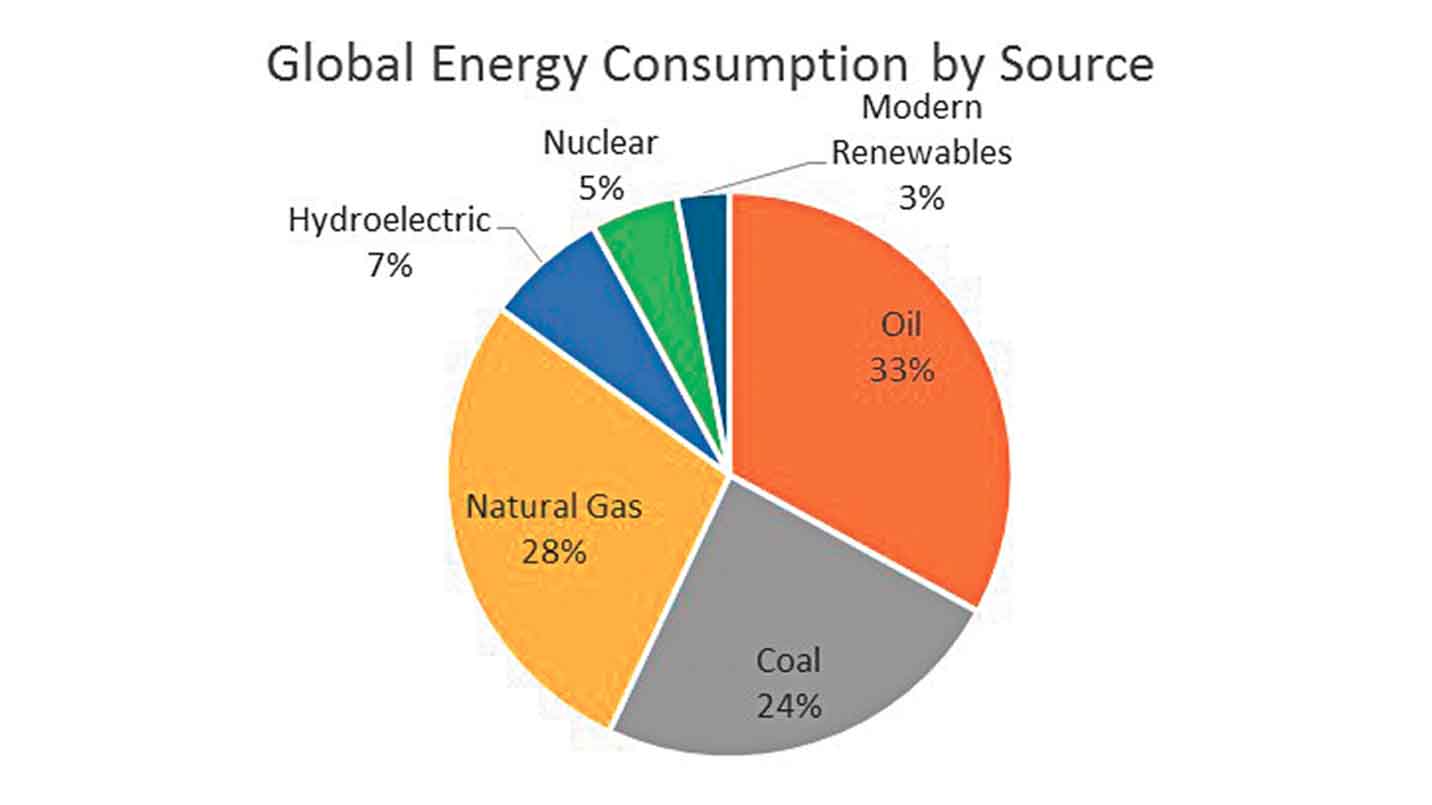

With improving sensitivities on the reserve stock of fossil fuels and an alarming rate of increase of Greenhouse Gas Emissions, there is a thrust to improve the fuel mix more towards renewables together with nuclear power. The International Energy Agency study estimates that the growth in renewables is expected to account for half of the growth in energy supplies over the next 20 years. However, traditional fossil fuels such as oil, gas and coal will continue to remain the dominant sources of energy powering cities accounting for approximately 75% of total energy supplies in 2035, a decrease from 85% in 2015.

Compared to the last two decades, the growing energy needs are being met with robust sustainable energy policies globally. The rapid decrease in costs, ease of implementation and improved peak load factor of renewable energy has resulted in tremendous capacity additions of solar, wind, geothermal and biomass gasification.

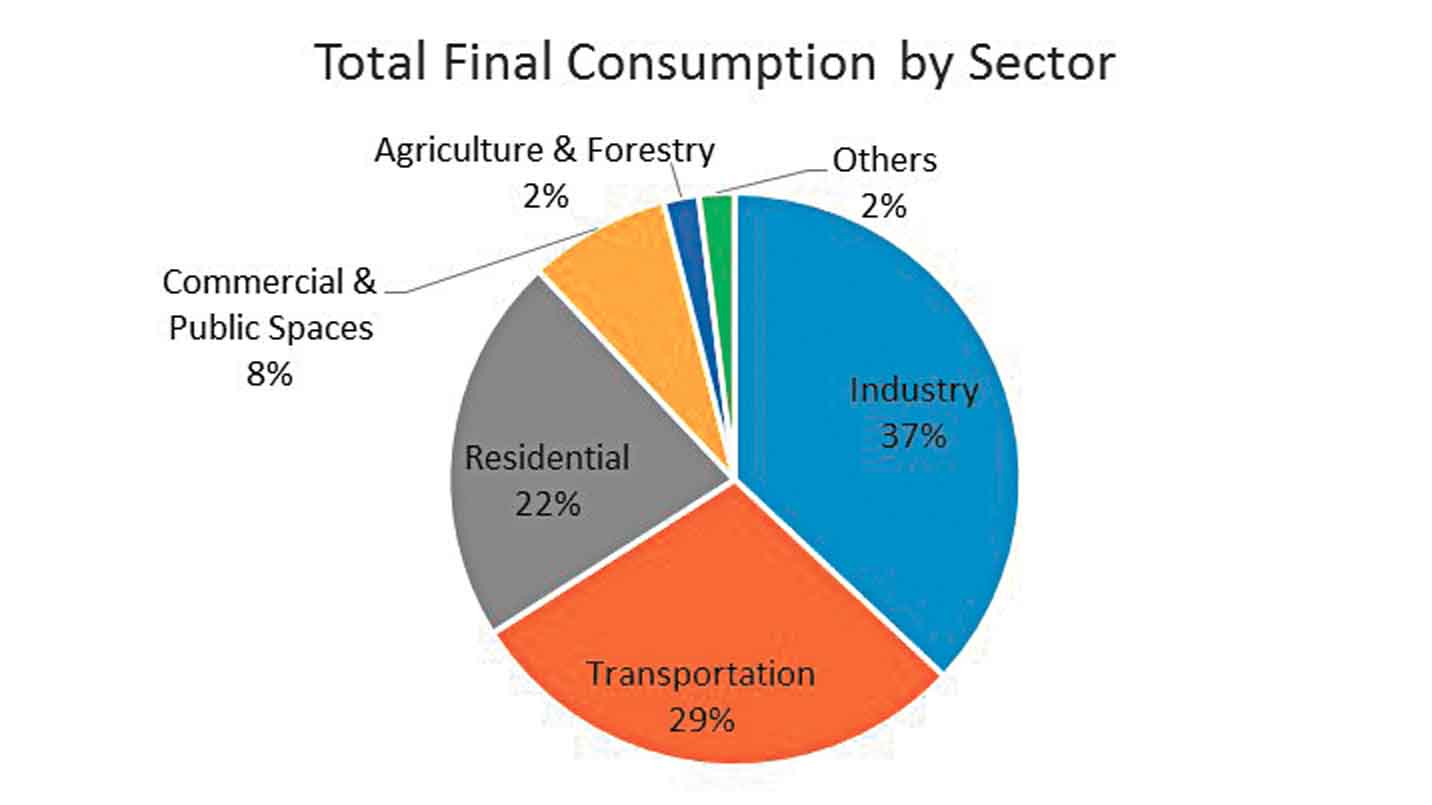

Statistics from the International Energy Agency and BP Energy Outlook suggest that in 2015, oil continued to remain the world’s leading source of fuel accounting for 33% of the global energy consumption. Roughly 63% of the oil consumption is used in the transportation sector. Use of coal has declined over the years, however it still continues to generate 40% of the world’s electricity. Transition to a better fuel-mix will result in a sharper decline in the use of coal in the years to come. Natural gas is the second largest energy source in power generation, representing 22% of electricity generated globally.

The energy use in the transport sector is 29%, but is also responsible for 14% of the Greenhouse Gas Emissions. The energy use in the transport sector will continue to increase with rapid urbanisation and people opting for personal vehicles. The building sector, comprising of both residential and commercial spaces, accounts for 31% of energy use has witnessed a lower growth in energy use, driven predominantly by energy efficiency management systems for buildings and stringent energy conservation building codes.

|

|  |

Power Infrastructure and Markets Within Cities

Electricity is a key input and integral part of the life and economic growth for people in cities. Electricity is a secondary source of energy; it is produced from other sources, primarily mechanical energy into electrical power. The power infrastructure in cities consist of three distinct services: Generation - power plants, Transmission - grid power lines that carry electrical power over long distances and Distribution - where electrical power is transmitted at lower voltages and over smaller distances to individual end users like the industrial, commercial and residential customers.

Though electricity is a commodity, the power markets deviate from standard economics in two ways: first, the supply and demand must be in balance on the grid at all times, as electricity generated cannot be stored and needs to be utilised as and when it is produced. Secondly, a major portion of the demand side is disconnected from the actual supply costs. These unique attributes have led to electric power companies owning the entire infrastructure right from the power plants to transmission and distribution infrastructure, which is viewed as a natural monopoly. To prevent monopoly providers from misusing their status, there are regulators, mostly government bodies or third party agencies, that set terms of service and conditions on these monopoly providers for pricing policies, operating conditions and installed capacities.

The decades of the 1980s witnessed accelerated reforms and restructuring in the power market. Parts of United States, Europe and countries such as Australia, Philippines and Chile had regulators experimenting with deregulation of prices for generation. Consequently, the power markets were unbundled and broken apart into separate commercial entities responsible for generation of one part and transmission and distribution of the other part.

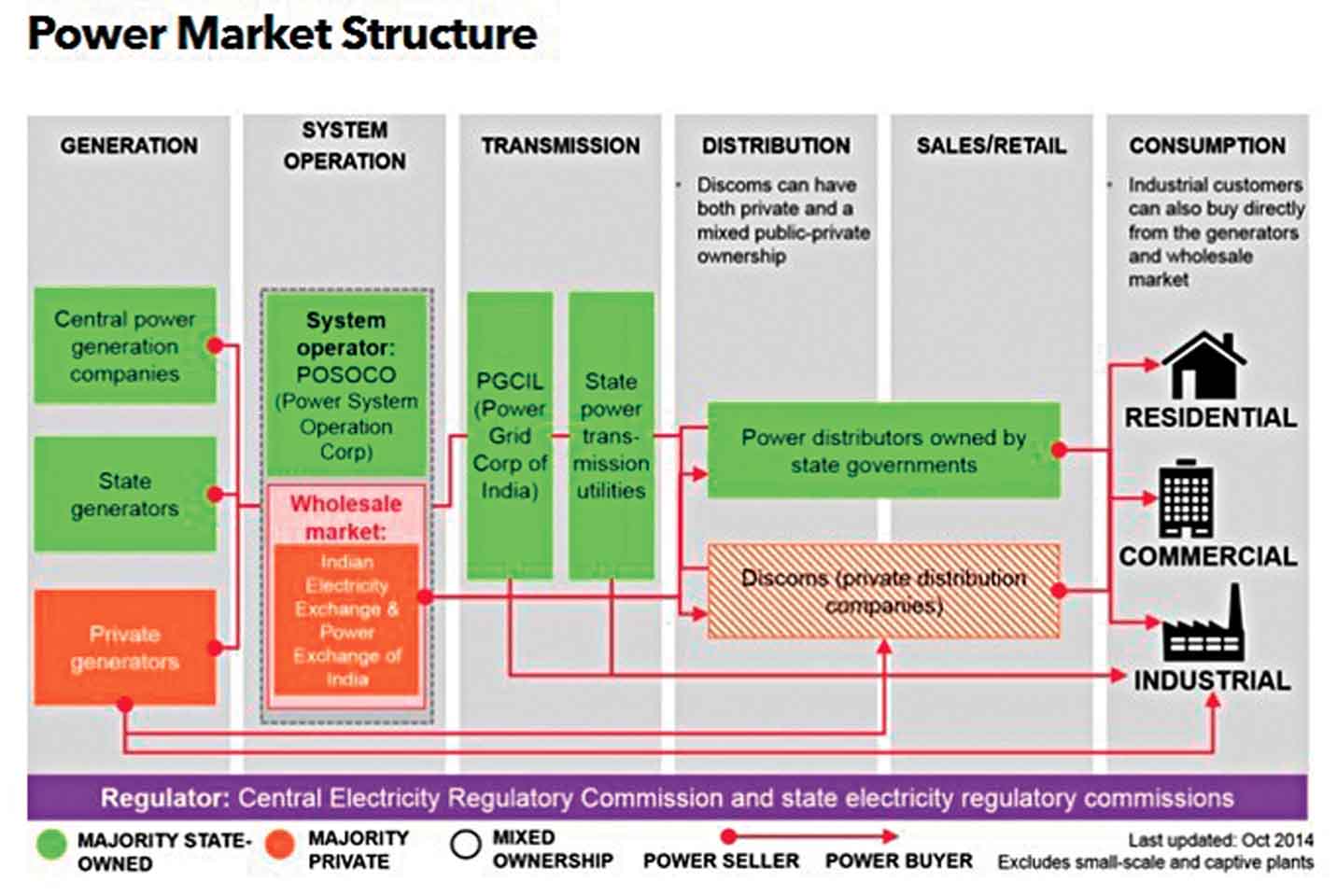

In case of developing countries like India, the power market restructure (as shown in the figure above), enabled the entry of Independent Power Producers and encouraged the development of renewable energy power generation by imposing obligations for purchase of power from such facilities.

The major change that can bring about phenomenal energy savings by the end users is through lowering electricity consumption

Major issues with energy in cities

Access and reliability: Access to energy has always been looked at through a rural perspective, but it remains a major urban problem. Cities are struggling to provide clean, affordable, reliable energy for all their residents. It is estimated by a World Bank study that 132 million people in urban areas lack access to electricity and 482 million people do not have access to clean fuel to cook food, which results in increased indoor air pollution. Setting up power infrastructure to meet the demand is very capital intensive and time consuming.

Regular power cuts resulting from load shedding when the demand is high from the commercial and industrial sector is a common feature in Asian and African countries. Further, with the increase in the number of informal settlements, providing power would be setting a precedent of legitimising these settlements, which is worrisome for governmental bodies.

Affordability: The challenge to meet the energy demands of the city and also to provide energy for all, results in impeding the transition from fossil fuels to cleaner and efficient technologies due to high costs. Many developing nations face high supply costs on petroleum products due to uncontrollable inadequacies in the supply chain. These high energy costs, further increase the price of the goods and services affecting the basic energy needs of the urban poor. Energy is often used as a political tool with subsidies granted to all, affecting the financial health of the power generators and operators. There is a need to eliminate subsidies granted on energy generated from fossil fuels and transition towards incentivising use of cleaner fuels.

Air Quality: Fossil fuel combustion in industrial processes, thermal power plants, space heating and vehicular exhausts result in Carbon Dioxide (CO2), greenhouse gas, particulate matter, SOx and NOx emissions. Energy choices will have a significant impact on the environment and human health. Cities contribute to 80% of the Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Policy attention on moving towards a low carbon city by increasing energy efficiency potential, scaling renewable energy power generation, pollution control measures and initiating technological advances in carbon capture and storage will be essential.

|

Developing a road map for sustainable energy practices in cities

Urban density and spatial distribution are two key factors that influence energy consumption, specifically in the mobility and building sectors.

Lowering consumption: The major change that can bring about phenomenal energy savings by the end users is through lowering electricity consumption. Every unit (kilowatt hour) of power saved is equivalent to two units of electricity generated. This can be achieved either by using energy more efficiently, i.e. adopting appliances and technologies that consume less energy or by reducing the amount of services used (driving less, using mass transit systems or using car pools).

UJALA, a programme under the flagship of the Government of India to provide affordable LEDs to domestic consumers without subsidies, is being implemented by Energy Efficiency Services Limited (EESL) across 120 cities in India. It is estimated that this programme will help in reducing the annual household electricity bills by about 15% , electricity bill savings will be to the tune of ` 16 billion every year, reduction of carbon emissions by 3 million tonnes per year and 4 terawatt hours per year of additional generated power available for other uses.

Urban Planning: With increase in urban sprawl, the city grows horizontally, leading to more travel, more fuel consumption, increase in capital expenditure for new infrastructure and services, causing high energy inefficiency. Compact and dense cities require less energy to move people and goods around. Planned distribution of residential and commercial areas along the transit corridor and mixed-use development reduces dependencies on use of personal vehicles for commuting. It is thus essential to integrate spatial, transportation and infrastructure plans for being more energy efficient.

The city of Hannover, Germany tackled social inclusion and affordable housing by creating an Eco District: Kronsberg. The city was planned for high density and ambitious energy optimisation standards through low energy homes, efficient district heating and electrical systems. A direct transit corridor linking to the city centre, with dedicated lanes for bicycles and a dense layout of footpaths to promote non-motorised transport, augmented this plan.

Energy Efficient Transportation: Cities need to be built for people rather than vehicles and this calls for bringing in an efficient transportation system. To cut the use of fossil fuels, emphasis should shift towards non-motorised transportation encouraging walking and cycling, developing mass transit systems, optimised trip scheduling and use of efficient fuels.

The network of bicycle sharing in Barcelona consists of more than 420 stations to lend and return over 6000 bicycles distributed throughout the city located near public transport stops and provide efficient last mile connectivity.

Energy Efficient Buildings: Buildings have the largest potential and many avenues for energy savings. Considering the fact that 75% of the building stock will be constructed in developing countries in a hot and humid climate over the next 50 years, it becomes an essential sector to tap for maximum energy conservation. The largest use of energy in buildings is attributed to its heating or cooling loads. New buildings should be constructed to support adequate day-lighting, ventilation, passive cooling and heating. Existing buildings offer energy efficiency scope with introduction of building insulation, green roofs, solar thermal water heating and transitioning towards energy efficient lighting.

Indira Paryavaran Bhawan, New Delhi India, the office building for the Ministry of Environment and Forest (MoEF), is the first on site ‘net zero’ building that features a passive solar design. The building is designed to use 70% less energy compared to a conventional building. It has its own solar power plant, water recycling facility and geothermal heat exchange system

Boosting Renewable Power: Renewables offer alternative sources of energy, which are less carbon intensive. The renewable power market is growing rapidly, with a thrust from government policy initiatives, energy security, reduction in costs and better energy output. The biggest deterrent is that renewables do not offer continuous power supply and they need be used in conjunction with traditional power sources to overcome intermittency. Renewables also offer the freedom of decentralised power generation.

Copenhagen, Denmark has an offshore windfarm at Middelgrunden with a capacity of 40 megawatts, generating 4% of the total electricity demand for the city.

Reykjavik, Iceland has pioneered the use of geothermal power for space heating. Almost 100% of the city’s energy demand is met through renewables: hydroelectric and geothermal.

Circular energy systems for industries and commercial centres: Industries and commercial sectors such as hotels, shopping malls and entertainment places define the new urban life and are major consumers of energy in cities. A circular energy system attempts in transforming unutilised energy into a resource or energy source for other functions. This circular system can manifest in terms of ‘co-generation’: simultaneous generation of two types of energy from a single source, and ‘waste heat recovery’: an energy recovery system from hot streams.

Rotterdam, one of the largest industrial harbours in Europe, established sustainable infrastructure in 2015 that connects the higher temperature effluent from industries and its waste incinerator to the city’s central heating system connected to residential homes and commercial office spaces.

Efficient Power Transmission: In developing countries, the transmission and distribution losses are high, especially in India, which accounts for almost 20% of electricity generated that is attributed to the inefficiencies in the grid management system and pilferages. Introduction of smart grids along with smart metres and smart appliances will help to account for energy consumption, optimise conservation and delivery of power. Roll-out of smart grids is very recent with countries formulating objectives and goals in energy efficiency.

Energy security and low carbon technologies are key factors that will power a sustainable future for energy in cities. Each city needs to assess their unique local settings, geographical advantages, available resources and economical base to meet their energy requirements.

There is a need for an integrated approach in policy making, planning the city’s spatial form, encouraging use of public transport, decentralising renewable power generation and incentivising energy efficiency. This approach needs to be augmented further with continuous awareness generation and sensitisation amongst consumers. A collaborative effort of industries, governments, research and academia, civil societies and citizens is needed to empower cities to transition towards a better energy future.

Comments (0)