The conscious design of public spaces in a city, particularly as a sequence of carefully conceived visual and sensory experiences along a walk or drive is one of the important aspects of the art of urban design. A case in point is the vast network of streets of traditional European towns that translate literal urban design vocabulary into stretches of visual and physical built form. History courses through these intimate streets, like various scenes unravelling in a play. The sequence and scale of open spaces and built form together trigger a sense of identity and belonging for both residents as well as people in transit. The urbanists responsible for such experiences carefully carved out striking visuals ranging from traditional and intimate courtyards with fonts, to tree-lined avenues with impressive architectural blocks made with modern materials. Art abounds in these streets in the guise of impressionable urban compositions, inviting people to participate in both the sacred and the profane rituals of daily life.

City on the Coast

Just off the southern coast of France lies Montpellier, a former port and traditional university town. Founded in 985, an 11th century wall outlines the city’s concentrated urban citadel. Montpellier occupies an important seat of research and learning, with its principal universities in the fields of Law, Arts and Medicine dating from the mid 13th century. Montpellier serves as an urban laboratory, with a slew of internationally acclaimed architects, such as Ricardo Bofill, Sou Fujimoto, Jean Nouvel and Zaha Hadid, invited to reimagine and redefine the urban form and character of the city.

The excursion on foot through Montpellier covers three distinct zones, each with its own configuration of urban form and open spaces.

The First Stretch

The historic core of Montpellier or L’Éccuson (The Shield), is a dense, organic urban quarter with La Place de la Comédie as the jewel in its crown. Over the years, buildings have been subjected to adaptive reuse and renovation, all the while retaining the essence of the history of the settlement. The old city has evolved, with the removal of the city walls, insertion of new roads and introduction of a dedicated tramline network.

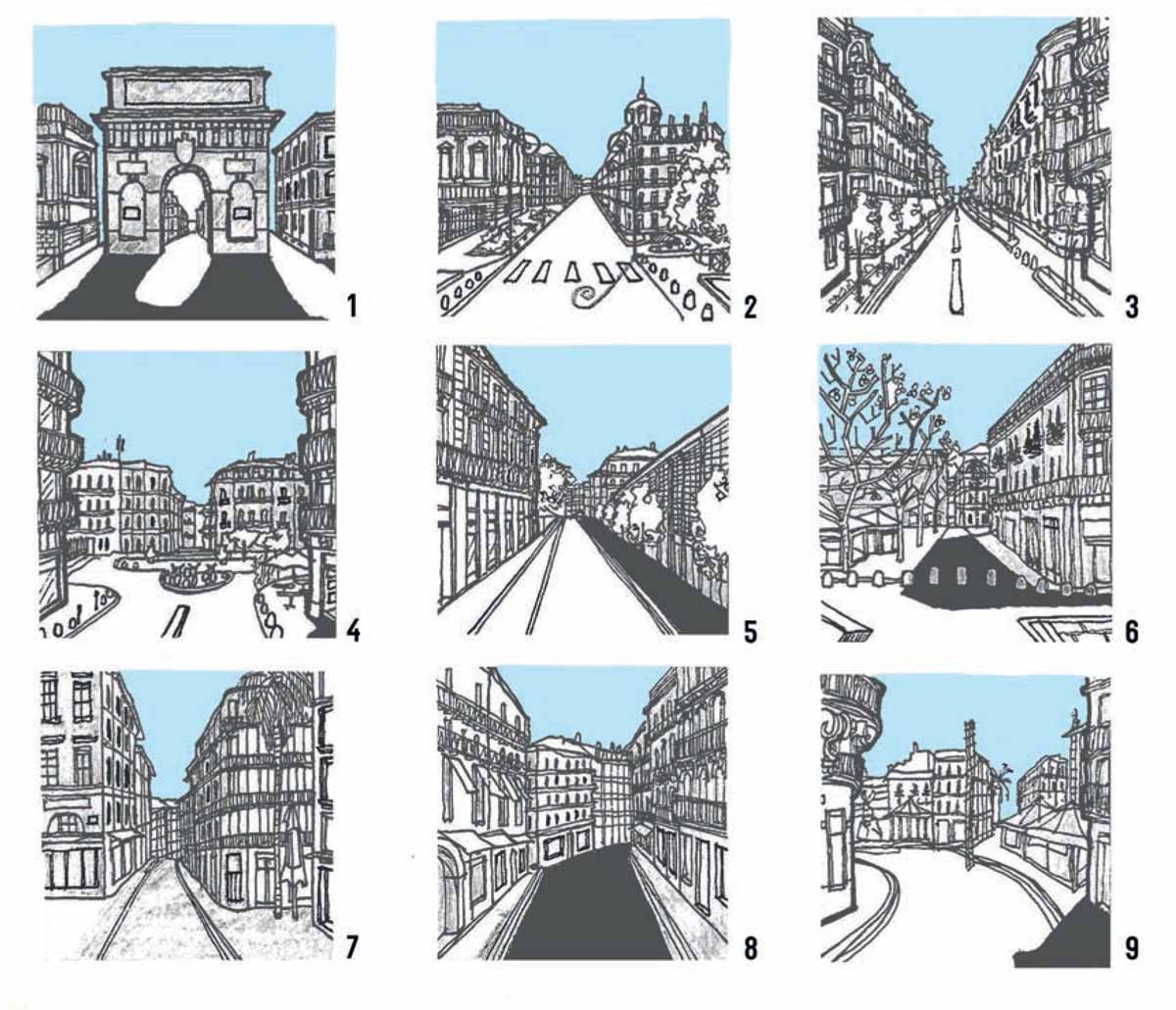

1. We start our walk at the the Porte du Peyrou, and move eastwards. Located on the eastern end of the Jardins du Peyrou, it is comparable to L’Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile in Paris. The monument was designed in 1690 by Francois d’Orbay, who was involved in some of France’s most iconic landmarks, notably Le Louvre museum and Palais de Versailles. The Porte du Peyrou serves as an entry portal into L’Eccuson.

2. Rue Foch begins here, with the stepped Cour d’Appel (Courthouse) de Montpellier on the left side and an administrative block on the right with off-street parking.

3. Further down Rue Foch, the streetscape is reminiscent of the grand avenues of Haussmann’s Paris. The five storey Mansard roof structures lining the road break off into smaller lanes.

4. Rue Foch culminates at the Place Martyrs de la Resistance and is enclosed by the Préfecture de l’Herault, the Post Office block and some mixed-use blocks. There are entrances to underground parking facilities in this area. The central island is complete with a fountain, seating space, some large urns and a few trees.

5. The space o to the right of the island, Espace Philippe IV de Valois, leads into the shopping and eating zone.

The relatively new, single storey block, Les Halles Castellanes, on the right, is a covered market where fresh produce is sold.

6. Further along, is the Place Jean-Jaurès. It is an excellent example of a public open space that is used for social events, while also accommodating a string of street cafés and restaurants.

7. Rue de la Loge begins here and is a pedestrian-only shopping street.

8. The street indicates a small pause point in the form of a circular junction at the right turn. Buskers set up here on the average day. The blocks are mixed-use in nature with the ground floor displays showcasing clothing, books, food and drink.

9. The intimate Rue de la Loge spills into the Place de la Comédie, one of the largest squares in Europe. Till the mid-1960s, this space served as a solitary, oval-shaped trac island (L’Oeuf). With the introduction of new development reforms, the island was converted into a large public space that is actively used today.

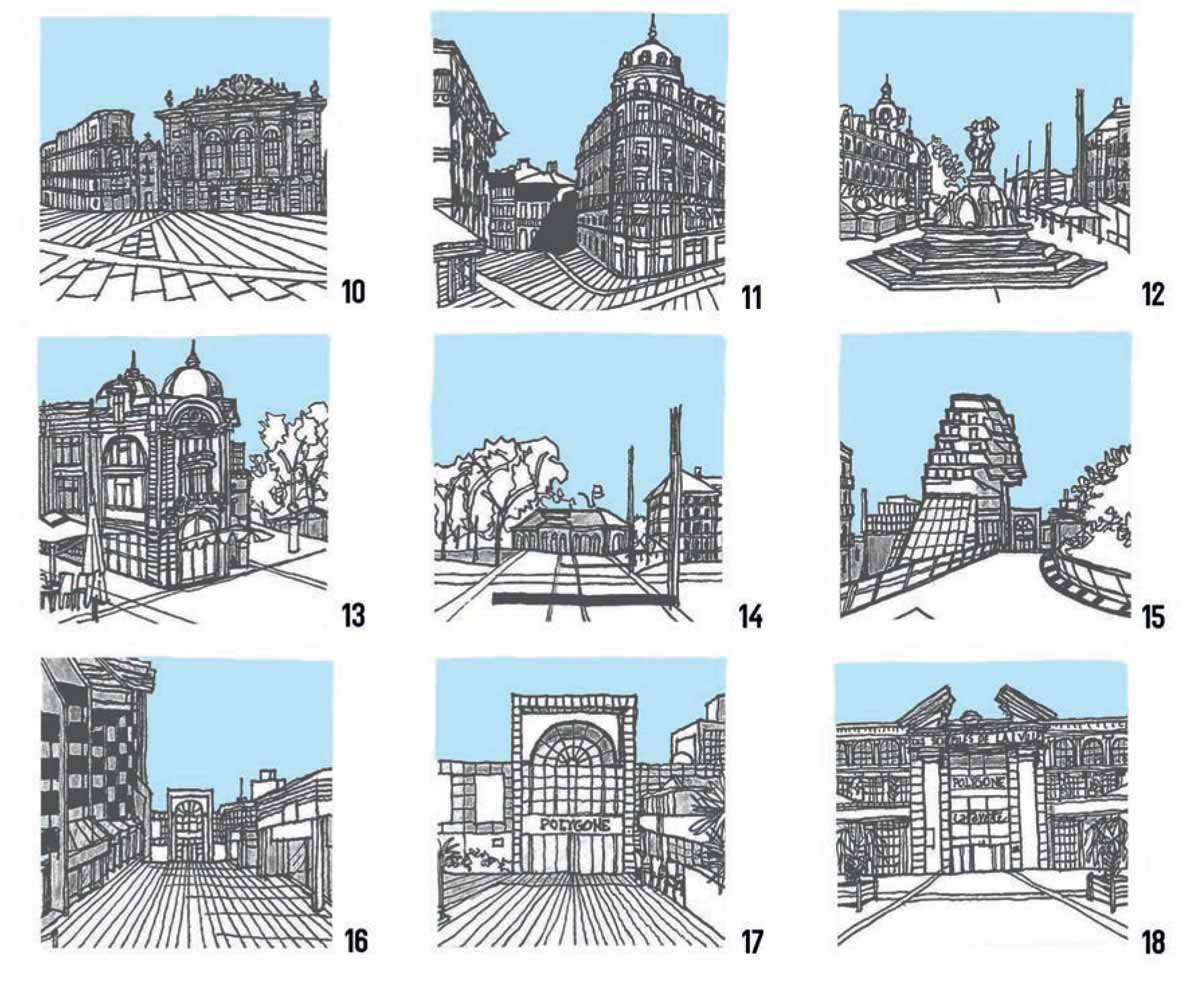

10. Place de la Comédie is flanked by many historic buildings such as the 19th century Italian style opera house on the western point (Opéra Orchestre National Montpellier Occitanie).

11. Standing with one’s back towards the opera house, a mixed-use block comes into view, that was formerly a department store, Galeries Lafayette. The mansard roof corners are bulbous in shape resembling deep-sea diver helmets.

12. A fountain stands in the middle of the square called the Three Graces, designed by sculptor Estienne d’Antoine in 1790. This place is frequented by locals, tourists and students on a daily basis and makes for a good meeting point.

13. The easily recognisable Gaumont Theatre sits along the periphery of the square next to the Galeries Lafayette block.

14. Place de la Comédie towards the east, branches into two paths: one towards the tree-lined Esplanade Charles de Gaulle and the other towards the shopping mall, Polygone. In thedistance, the Tourist Office can be seen.

15. The Triangle comes into view at this point. This route is frequently used by pedestrians cutting through the clutter of traffic and the steep terrain since the mall is fitted with escalators galore.

16. The edge conditions here give rise to three complimentary functions: hotel services on the left, eateries on the right and shopping straight ahead past the rear entrance to the Polygone.

17. The entrance resembles a semi-circular French window enclosed within a rectangular frame. This is yet another type of entry portal leading into an enclosed environment.

18. Place Paul Bec is the main space in front of the main entrance to the Polygone.

The classical Renaissance style building, with its many fenestrated levels, consists of a graduate school, a library, office and shops. The space often hosts events targeting students in the area.

The Second Stretch

Ricardo Bofill’s Antigone lies on the opposite side of the Polygone. The project covering 36 hectares, was started in 1979 and completed in 2000. It is a vast, postmodern commercial and residential complex, built on former military grounds that occupied the site. Despite its grand scale and classical exaggerations, Antigone succeeds in shaping large public spaces and creating a strong pedestrian axis southward. In essence, this project acts as a connection between the old historic centre and the district of Richter across the River Lez.

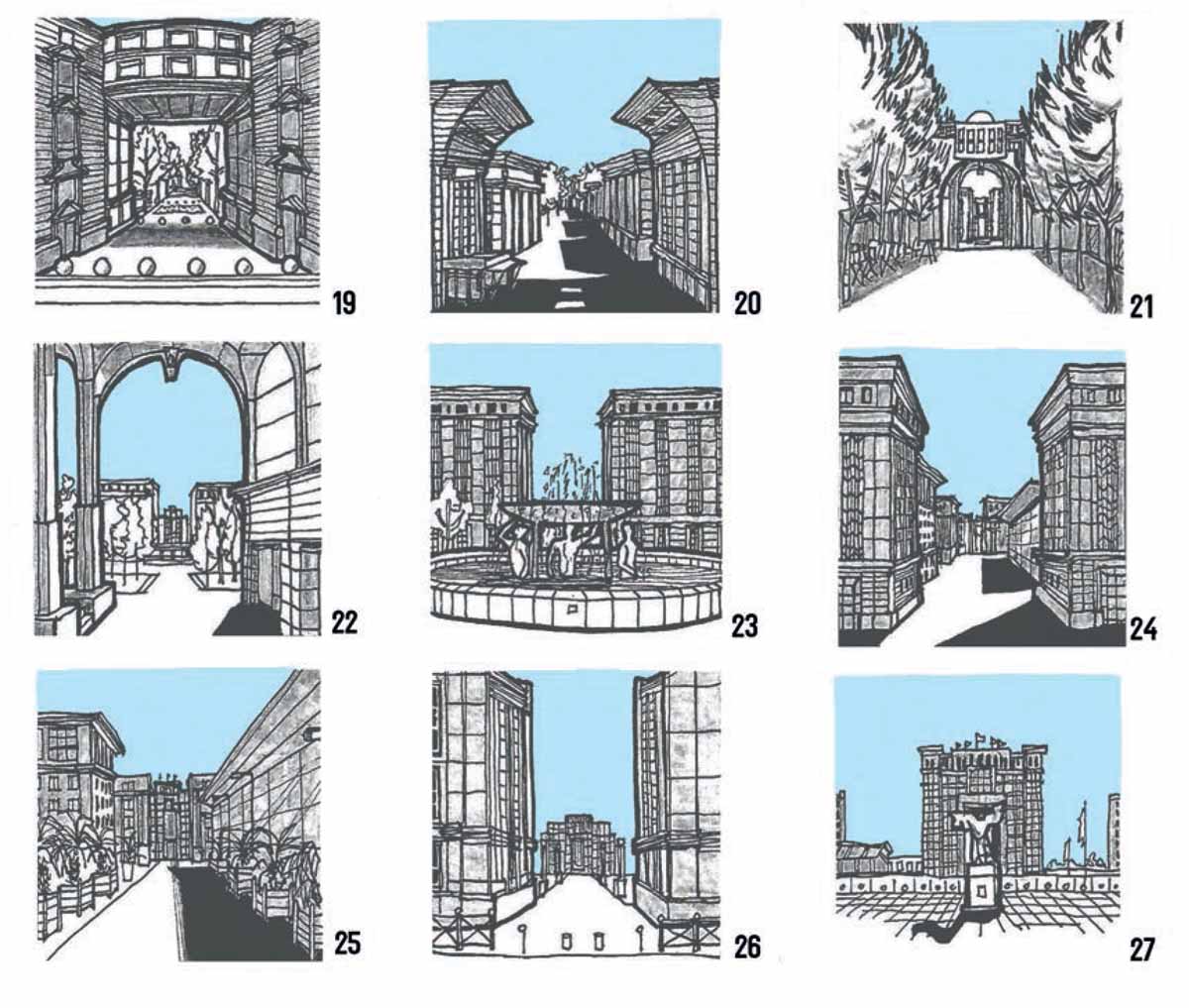

19. After crossing a tramline track, the palatial entrance into Antigone emerges. A square archway cuts into the building offering a glimpse of the courtyard, with the fountain, Poseidon, inside. Lined-up round bollards prevent vehicles from entering the compound.

20. The Antigone’s Place du Nombre d’Or takes on the form of a partial cruciform in plan. The height of the buildings in this parcel is about seven storeys. Informal farmer markets set up shop here on fair weather days.

21. In the entire configuration, monumental gateways lead into different types of open spaces. Along the Place du Millénaire, the line of buildings on either side have shops on the ground floor and the street is dotted with trees.

22. After crossing Rue Léon Blum, the portal of Place de Zeus grants further access. It houses the main information services department of Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole.

The shaded vaulted space frames the next sequence of squares.

23. A pause point in the form of a fountain fitted with three human sculptures, Trois Éphèbes, occupies the centre of Place de Théssalie. The two mirrored Parthéna blocks occupy the backdrop.

24. From this point, it is clear that no more immediate open spaces are visible. Instead, a line of buildings gracing both sides of the street come into view.

25. After crossing Rue de l’Acropole, the newer addition of buildings emerges: a municipal library, a swimming pool and recreational centre, and Place Dionysos.

26. After crossing Rue Poseidon, a pedestrian path runs into a massive, semi-circular expanse, Place de l’Europe, and is bordered by similarly shaped perimeter blocks, Esplanade de l’Europe.

27. At the end of the Antigone overlooking the Lez, the Statue Allégorique de la Victoire faces the viewer and is framed by the glass-clad Hôtel de Région, the regional seat of government, completed in 1989 by Bofill.

The Third Stretch

Consuls de Mer is a neighbourhood on the banks of the Lez, conceptualized in 1991 by Rob Krier and Nicolas Lebunetel. The design of the clusters of town buildings with painted facades and height variations is centred around public and semi-private courtyards. The district is spread over 12 hectares with about 2,800 homes, including social housing, student residences, and shops at street level. Across the Lez River, Adrien Fainsilber’s Richter quarter has a sprawling university campus along with a mixed range of commercial and residential development along the riverfront, easily accessible by the tramline network.

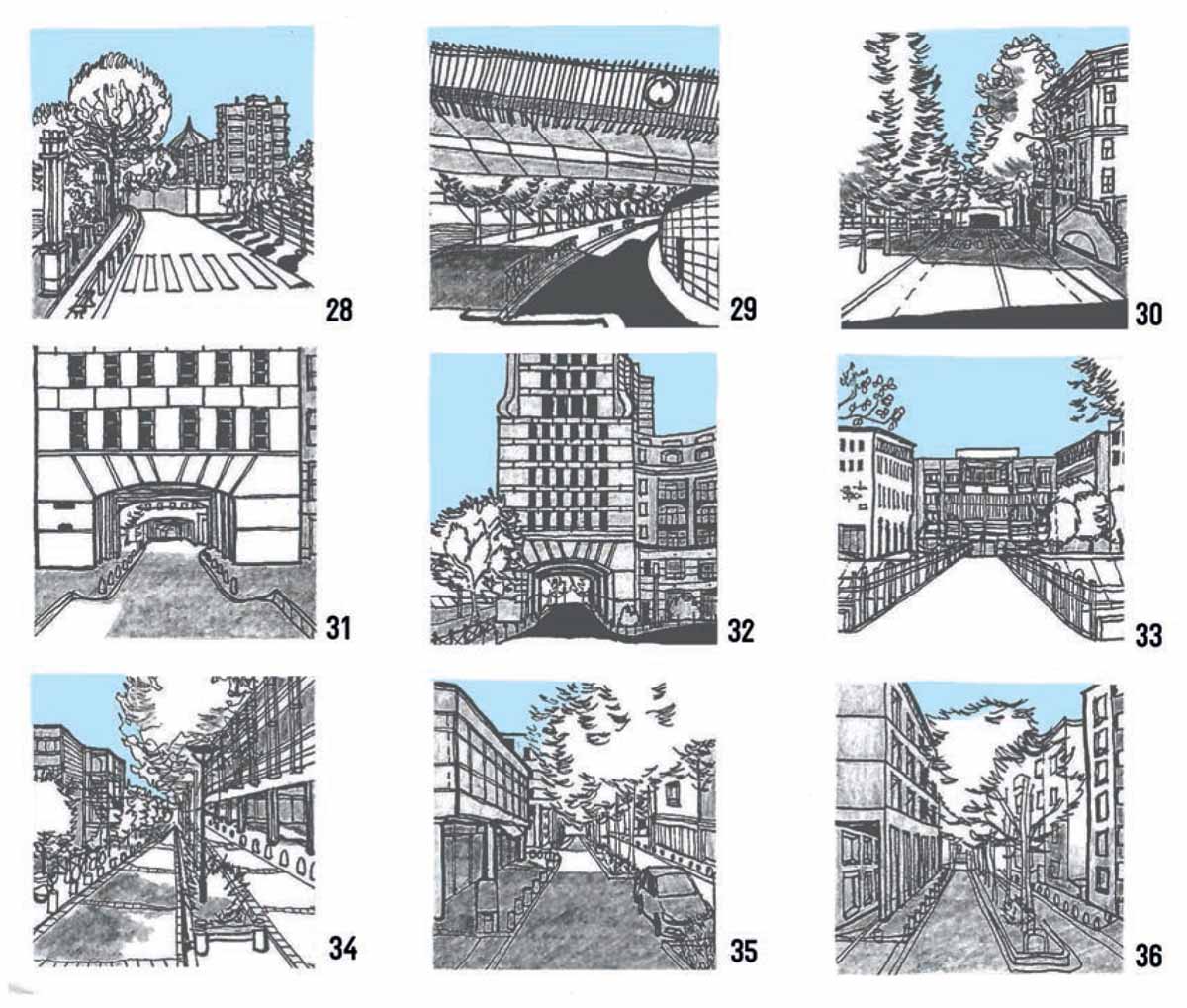

28. Along the Avenue du Pirée, one crosses into Consul de Mers. A promenade with street furniture runs along the left and a few residential blocks can be seen in the distance.

29. After passing under the bridge, Avenue du Pont Juvenal, the road travels further along the edge of the Lez. A line of trees can be seen along the left, rearming the promenade boundary.

30. Clusters of residential buildings and flights of steps, typical of Krier’s New Urbanism roots, can be seen on the right.

31. This passage cuts through the building blocks here and leads into Place Jean Bene.

32. Two stone-and-concrete tower blocks dominate this small roundabout. Avenue du Pirée continues onwards. There is a statue in the centre of the roundabout as well as two offshoot roads: Chemin des Barques and Boulevard des Consuls de Mer.

33. From this point, a small footbridge or passerelle, Place des Barons de Caravettes, connects to the university campus area, Espace Jacques Premiere d’Aragon.

The sloped lawns along the river banks are frequented by joggers, dog walkers and students.

34. Rue Vendémiaire contains a mix of student housing, residences, public facilities, offices and shops. A tree-lined median sits comfortably in the centre of the street. The glass and steel Faculté d’Économie block is seen on the left.

35. A public centre with oces and shops on the left with a running colonnade occupies this place. Residential blocks with balconies looking onto the street are found on the right.

36. The use of colonnades and arcades keeps in mind human scale while providing a covered space to walk.

From Old to New

Montpellier is a living urban artifact, dotted with a number of markers in the form of landmarks and pause points. Markers range from temporal entities (stalls, street buskers) to permanent structures (churches, shopping centres). Axial design, highlighted in Montpellier, promotes long formal vistas with strongly defined edge conditions. The unseen axis of centrality creates the distinct perception of a well organized city, not in excess but in justified proportions. Montpellier’s streets are containers of public life, offering vivid lessons on how contemporary public spaces can be conceived as physical artistic realms in which activities take place.

Comments (0)