The biggest challenges facing housing in the urbanised world today are accessibility and affordability of a house for all. Cities around the world have delved into the idea of affordable living for decades with varied levels of urgency, focusing on different aspects of the problem and constructing solutions to address growing challenges of density.

Designers in South America have focused on affordability, unit type repeatability and onsite rehabilitation solutions for migrant populations living in the city. In Asia, examples have focused on large-scale rehabilitation in intensely populated and dense mega-cities in the form of site and service schemes as well as subsidised housing strategies funded by government grants to address the lack of formalised housing settlements.

However, in most of the western world, the housing challenge has been plagued by the concern to keep housing in cities affordable for all. Cities like New York, London, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Chicago have seen a constant rise in the housing markets forcing people out to the suburbs by way of constant gentrification making downtown and inner city neighbourhoods unaffordable for most of the population. While these cities have seen a constant rise in the price of housing, it has not deterred the steady increase of migration of highly-skilled, working-class individuals seeking employment opportunities in the cities. The skilled working-class population is represented by the single male/female between 25-35 years of age looking for an affordable housing solution without an excessive demand for space. This user type represents close to 52% of the total population in need of housing in urbanised areas of the city (Graham Hill, founder of the small-living site LifeEdited.com).

Thus, an urban dichotomy of an increasing demand for affordable living within steadily rising unaffordable cities requires ‘out of the box’ solutions. One such growing experiment in American cities like New York is the idea of ‘micro-living’: a relatively inexpensive idea to provide a compact yet comprehensive living environment for the single individual in a desirable and well-connected neighbourhood of the city.

There are multiple reasons why micro-living experiments are considered as popular living models for the future. Continuous economic uncertainty and job instability are leading many urban individuals who could afford larger residences not to part with their hard-earned money for high rents. There is a desire to live at a walkable distance from work and in urban cores and neighbourhoods with a strong social life. Finally, young single professionals yearn to live alone.

An interest in smaller spaces, apart from being a practical solution, is also a reflection of the changing demographic of the apartment dweller in the 21st century. A growing trend of delayed household formation, an increase in single-person households, a decrease in car ownership and an overall tendency to accumulate fewer belongings and participate in the sharing economy has contributed to the rising demand for smaller affordable living solutions and amongst all examples of this the most radical is the idea of micro-units.

What is a micro-unit?

A working definition of a micro-unit is a small studio apartment, typically less than 350 square feet, with a fully functioning and accessibility compliant kitchen and bathroom. However, different cities have different sizes of apartments that, as per the state’s norms, qualify as micro-unit apartments. But the main restrictions applied on such developments come from the Zoning for Quality and Affordability norms, which encourage a variety of apartment types within a development thus restricting a developer to build an entire development comprising only of micro-units. However, legal restrictions notwithstanding, developers have shown a keen interest in micro-living and it promises to be the next big typology to become a ubiquitous phenomenon in cities around the world.

There are reasons for this:

• Micro-units are known to outperform conventional units in the marketplace. They are able to achieve higher occupancy rates and garner significant rental premiums (rent per square foot) compared to conventional units.

• Developers who have experimented with micro-units acknowledge that rental apartment communities that have a higher percentage of micro-units are more expensive to build since more units are placed on offer on the same property but a rent per square foot logic more than compensates for the added cost.

• Micro-units provide the possibility of living in relatively inexpensive units in highly desirable or expensive neighbourhoods close to work and social life.

Micro-units have displayed flexibility in the form of solutions that have been adapted both for the working-class single communities in cities like New York and Seattle, as well as ideas for state/city sponsored schemes for the homeless and the impoverished population of cities like San Francisco. Two recent examples of micro-unit developments illustrate this flexibility.

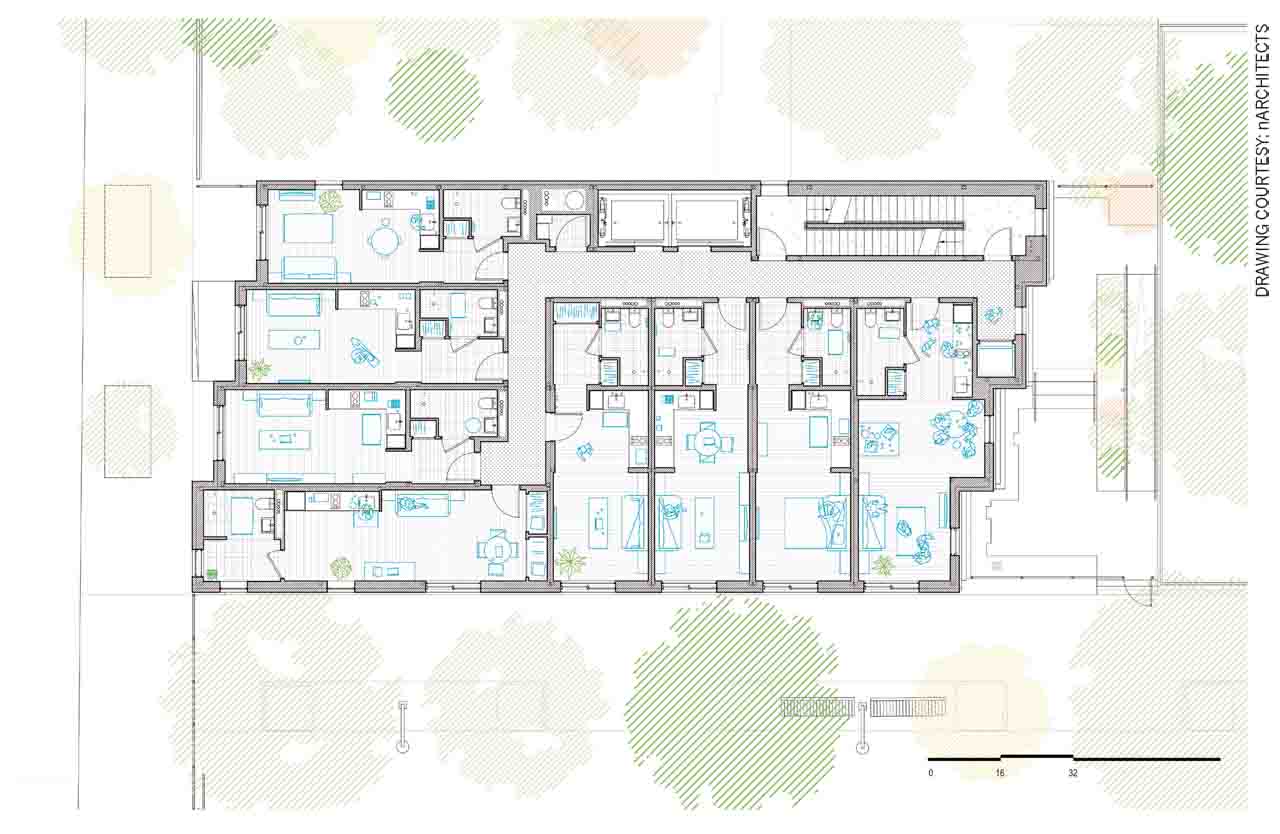

Carmel Place, NYC by nArchitects

As per nArchitects, Carmel Place provides a ‘systemic new paradigm’ for providing affordable housing in cities, which face such challenges. More than 60 percent of all New York households comprise one or two people, yet there is scarcity of studio and small-sized one-bedroom apartments in the city. In the 1980s, zoning laws were introduced in New York that prevented apartments from being smaller than 400 sq. ft.; a recent amendment to that law has allowed for smaller apartments to be re-introduced into the market. Carmel Place was a pilot project for this zoning amendment and was the winner of an open architectural competition for micro-dwellings organized in 2012 by then mayor Michael Bloomberg in order to serve as a new model for affordable housing for single and two person households. The project comprises 55 units, which range in size from 250-370 square feet. This tall, narrow nine-storey building is composed of four slender stepped volumes and was pre-fabricated offsite with the possibility of quick onsite assembly thus reducing the construction cycle and therefore the overall construction budget for the project. The success of the project lies in its compact yet efficient space planning that allows the dwelling unit to convert from a living room by day into a bedroom by night. Another equally important feature is that within a compact footprint the designers prioritised the feeling of a large volume with all units getting equal light, air and views of the surrounding neighbourhood.

Micro Pad, San Francisco by Panoramic Interests

The Micro Pad is designed as a housing solution for homeless people in San Francisco and other cities of North America. It is deployed in a fast and quick construction cycle of prefabricated affordable dwelling units on underutilized city-owned lots or other forms of government designated land. Each compact dwelling unit measures 160 square feet and comes fully furnished with a private bathroom, kitchenette, armoire, desk and bed. This solution reduces construction costs dramatically since the modules have been designed to be fabricated offsite in four weeks and the onsite construction process takes between four to six months to finish. The manufacturing company, Panoramic Interests, funds the project entirely and offers local authorities to rent out the modules on behalf of homeless people. Alternatively, the company offers a sale option where the local city authorities can eventually purchase the building.

Within growing urban challenges of increasing population and increasing inequality around the world there is an urgent need to find creative solutions for density and affordability. There are many compelling arguments presented by the idea of micro-living and micro-units in particular:

• The possibility of re-densifying our cities while maintaining focus on ideas of affordability.

• Providing housing solutions for those who cannot afford ever-increasing market rates.

• Proposing ultra-compact living solutions as affordable ideas to the city authorities in order to address problems of homelessness.

• Building more with less, condensing population and minimising our liveable footprint within a smaller area is a resourceful and sustainable way of perceiving the future.

The world is rapidly urbanising and densifying without a clear thought for the future. Micro-apartments are ideas that promise a large-scale positive impact on our urban challenges. It is an idea that is demographically inclusive, economically viable and designed for a sustainable future.

Comments (0)