Building Tradition

All over the world building with mud is a common way of construction. More than 50% of the world’s population lives in mud or loam buildings. In West African countries, this tradition is well known because of structures like the Great Mosque, the biggest mud brick mosque in the world which stands along the River Niger in Djenne, the white Grand Mosque Bobo Dioulasso in Burkina Faso or the tombs in Timbuctoo. Building with mud was logical for these locations along rivers. However, there is, of course, an immense diversity of techniques and skills. The method of building in Mali is not the same as, for example, in Yemen or Afghanistan and the differences have led to variety in architecture. Climate change has also been an influencing factor in this development.

The Dogon Country, now predominantly in the desertification zone, has a very long tradition of mud brick building and handmade loam granaries. There are even buildings built before Christ that were constructed with special techniques for handmade bricks. The ancestors of the Dogon people, the Tellem, developed this method 2500 years ago when there was much more water available. Today, this technique is still known, but only to a small part of the population. The buildings still exist because they are protected by the rocks and preserved by traditional repair work.

However, for contemporary building types, that traditional way of building is not a solution.

In the last century, there was a rising demand for new typologies to construct buildings such as schools. The government abolished the traditional techniques because buildings needed too much maintenance and did not appear as contemporary as the authorities wanted. The result: concrete block schools, plastered and painted in various colours. This led to the severance of any connection with tradition, architecture and vernacularism. Besides, the community couldn’t identify with the buildings anymore because they were not built as a part of the village. Local inhabitants couldn’t even contribute to the building process of communal buildings, which was once a Dogon tradition.

|  |

Finding the Road

Building in partnership brought about the road to change. Though there was equal respect for all partners, part of our work included guiding the project in the right direction and highlighting possibilities. Over a period of 20 years, 30 schools were built. The first school was built with traditional mud bricks, which had to be repaired every two years. Then we switched to natural stone blocks, but the mortar was expensive because of the enormous amounts of cement it contains. The concrete block schools that followed heated up and required a lot of energy for maintenance too. However, what was of paramount importance was the fact that people using these buildings did not feel connected to their community anymore. The turning point came with the reconstruction and restoration of the first school in the area, which is 100 years old today. It was built using the traditional method. That’s why it has a comfortable interior climate and is architecturally connected to the place and the community. The restoration of this building in 2005 opened our eyes. At that point, building with HCEB (hydraulically compressed earth blocks) became the new and accepted approach. It became the mantra of a progressive and modern way of construction with endless architectural possibilities and, at the same time, connected to the Dogon tradition. And so Vernacular Building 2.0 was kick started.

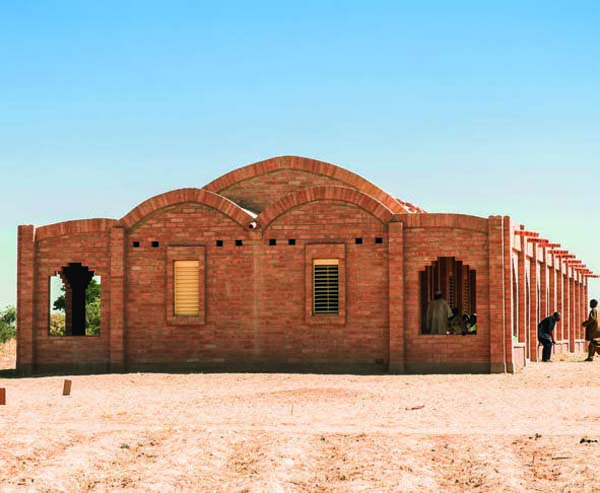

Primary School Tanouan Ibi

The Dogon plateau in Mali is underdeveloped, as the government hardly invests in this remote region of the country. Therefore, the development of new building techniques based on local construction methods, using local materials and training new masons, creates a spin-off for local development.

Primary School Tanouan Ibi aims to safeguard the education and social development of the young generation of Malians in this area. It was developed and built together with the local community as an equal partner. This creates the highest commitment and a sustainable future because it isn’t just any school building; it is their school building.

The school consists of three 7 x 9 metre classrooms for 180 pupils in total, a principal’s office, a depot and a sanitation building. In the evening, it is used to educate women. The school is located at the edge of the village Tanouan Ibi in the vast plain of the Dogon region, next to the rock face of Bandiagara (World Cultural Heritage of Humanity, Unesco 1986).

The architecture is inspired by local building traditions and culture as well as by function. In the tradition of the Dogon area there is a doubtless spiritual connection between men, culture and nature. Their minimalism in building with clay and the plasticity and immediacy of detail are remarkable. It is ‘wealth in restrictions’. Nuances, personality and soul define the building; a majestic gesture is not necessary.

|  |

All photos: LEVS architecten | |

The building is erected using modern technology and built by local, newly trained masons.

Because of the use of the newly developed HCEBs, the building withstands both hot sunlight and heavy rainfall much better than the traditional clay buildings.

These bricks are non-fired and are produced using the soil on site, which reduces production costs and environmental degradation. They also provide an optimal cooling climate. The use of these blocks of compressed earth for floors, walls and roofs, leads to a supple integration into the environment, corresponding to the way the Dogon villages fit into the landscape. The language of form is a clear consequence of functional requirements.

The structure of the school building is unique with two verandas running parallel to the classrooms. These operate as buttresses to withstand the weight of the barrel vaults in the roofs over the classrooms. The roof and the eaves have been accentuated by an additional layer of stones and by dilatation stones, separating the barrel vaults. A thick layer of red earth, mixed with cement in order to achieve a waterproof and water resistant layer, covers the roof. The gargoyles, manufactured by the local people called Bozo, guarantee the swift drainage of rainwater. Custom made ceramic tubes have been inserted in the roof to provide ventilation for a pleasant inside climate, to allow daylight to filter in and to make a starry sky visible. During the rainy season (two months), these tubes can be closed.

The openings in the facades, with their window frames and blinds, are painted in a fresh yellow colour. The intricate floor pattern of the verandas with their benches establishes a meaningful place for the elders of the village community.

Tanouan Ibi is only one of the HCEB-buildings that have been built in Mali. All these projects were a very practical and pragmatic challenge: constructing buildings to ensure that education can be imparted and also provide housing for teachers and various other facilities. All this was done in collaboration with the local people. The contractor and the craftsmen work closely together with the students of a technical college. They are involved in every stage of the construction process in order to improve and to refine the construction methods, linked to already existing techniques, traditions and know-how. Educating people in building engineering is an integral part for the development of construction techniques and local architecture.

Building Sustainably with HCEB

One of the most important issues to implement sustainable building methods is a careful study of available building materials. Using what can be found close to the building site to construct a building reduces transport costs to a minimum. The next important step is to design a building that will have a pleasant interior climate using the minimum energy possible. Each location asks for customised solutions. That is the true essence of sustainable thinking. There is no generic design solution that works all over Africa. In Mali, building with ‘hydraulically’ compressed earth blocks (HCEB) instead of traditionally compressed earth blocks (CEB) can make the difference.

Building with earth is not a new invention. Over the years, many different results have popped up. But then earth is seen as a cheap, inferior material only good enough for low cost housing or for use as a wall filling. The production of such blocks was generally done with a hand press and occasionally even without adding cement. Sometimes blocks were pressed under low pressure with machines. This gave rise to two problems: the blocks were too weak to be used to support construction and the detailing of the joint was not waterproof.

The secret of HCEB blocks is that they are manufactured using 20 tonnes of hydraulic pressure. The production process, the composition of ingredients and the method of processing them are constantly in development. The objective is to minimize the amount of cement, which is very valuable because it needs to be imported. Even for the hydraulically compressed earth blocks, which contain less than 5% cement, it makes up 85% of the cost. The machine with which the earth or loam is pulverised is the key. If the grain is uniform, it is possible to make bricks that can bear up to 5KN (kilonewton). That means that an HCEB has completely different qualities than the earth bricks produced elsewhere around the world.

Without any cement, HCEB can be used for the indoor walls, for instance. They can also be used as floor stones and tiered roof stones, which require different characteristics. In the beginning the bricks were mostly produced in the factory in order to control the production process.

Since 2011 the bricks have been produced on site, which has a significant effect on the transportation costs.

Building with compressed earth blocks demands a new approach to architecture and engineering. It also offers many benefits. One of them is using local materials. Another one is that the physical structure of the bricks creates an agreeably ‘cool’ building climate that adapts to the outside climate and cools down quickly at night. The bricks have a very high compressive strength, so they can be used to build bearing walls, even in multiple layers. Over the last few years we have made several designs for schools, housing, technical schools and a town hall.

As Dutch architects we have a broad tradition in designing brick facades and brick patterns. The dimension of buildings is based on the size, the natural quality and the possibilities of using the bricks. Within these limits we learned not only to use it as construction material, but also as decorating elements with a variation of patterns and reliefs. The buildings become more and more refined in their architectural expression. The reinterpretation of local traditions is a modern way of integrating the new buildings in traditional settings.

All photos: LEVS architecten

Comments (0)