The Moskva River’s wide affluent S-shape stream crosses the Russian capital from Northwest to Southeast. Unlike the Seine, the Neva or the Vltava, it cannot boast an elegant facade of aristocratic villas or tenement houses. It is marked by a discontinuous chain of medieval convents and fortresses including the Moscow Kremlin itself. Nevertheless, the river has another stratum of outstanding yet underestimated historical landmarks: the industrial complexes. In the past, they presented the basic economic infrastructure of Moscow. Now, they look for a better future.

The past decades have witnessed a crucial turn in the perception of historical European cities. For ages, the city was there to rule and protect first; then trade gained primacy, until universities and museums began to gain cultural prominence in the 18th century. By the middle of the 19th century, industry had emerged as the economic heart and redbrick factories occupied new parts of European cities, taking up areas far bigger than their old centres.

Two centuries later, an irreversible process evolved: new technologies made old production lines unprofitable and the labour market dictated that revamped industries be moved outside Europe or, at least, out of big cities. For decades, life was coming to a standstill in the textile centres of Great Britain, the coal and steel enclaves of Germany and the colonial factories of the Netherlands, until dying out altogether.

Economic depression engulfed former industrial cities in the 1960s through to the 1980s and abandoned factory premises stood vacant, turning into unsafe and seedy zones, until the first squatters moved in. Artists, searching for spacious workshops, initially found nearly free shelter there, like Andy Warhol with of his Silver Factory in Manhattan, or the hippies taking over the abandoned military barracks of Copenhagen as a place for their pacifist state.

Their bohemian life with concerts, exhibitions and far-from bourgeois atmosphere attracted the attention of citizens, tourists, police, tax collectors, developers and authorities, who realised that those zones were not as hopeless as they seemed to be. Small businesses – cafes, galleries and hostels – gave way to expensive lofts and business centres under the impact of revitalisation and gentrification while the artists moved on to other unexplored areas.

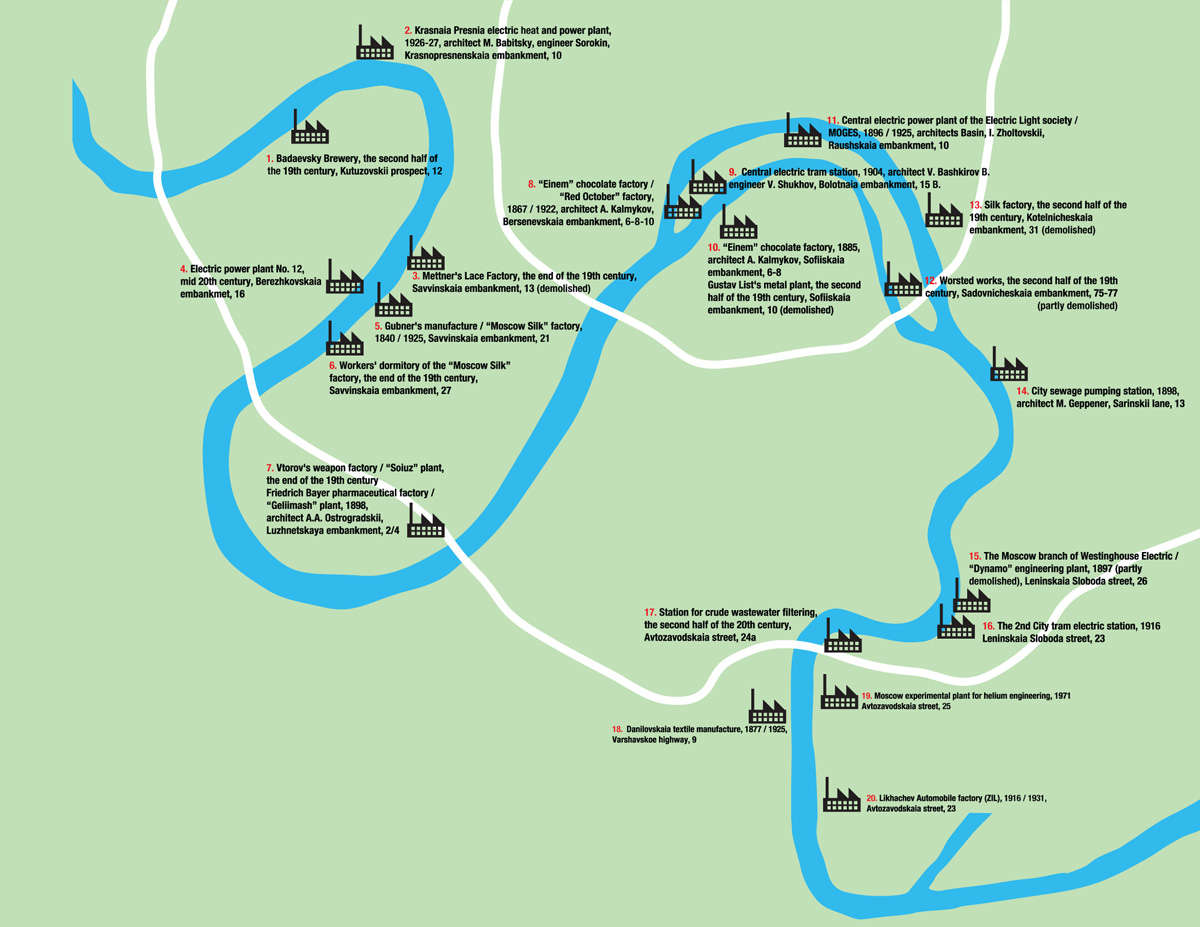

Moscow saw its earliest factories spring up in the 17th century with mostly food and textile production: silk, broadcloth and canvas. Later came the paper mills and glass factories and a veritable industrial boom took place in the second half of the 19th century with mechanical, engineering and electric plants. In the 20th century the old plants changed their names, but not their specialisation; new buildings were added to the old sites, but their durable pre-revolutionary equipment was still in use. As in many European cities, older Moscow factories and plants were often built next to the water. Most of the industries needed water for soaking, tanning, cooling, etc. A waterway was necessary to bring in raw materials and ship output; long before railways, the principal freight transport in Russian cities was barges.

With the Soviet-planned economy insensitive to market tendencies, Russia did not phase out industrial production within its cities until the early 2000s. Factories had been polluting Moscow air and production was shrinking from year to year. After the fall of the Soviet Union, outdated facilities and industrial decline forced the political decision to relocate all the factories outside Moscow’s borders.

Old redbrick factories were mostly built as private ventures, family businesses or concessions. After the 1917 Revolution they were nationalised and given to the state. In the 1990s they underwent a process of privatisation: the workers got their shares, but wealthy developers rapidly bought them. Consequently, each site became the property of a specific owner now capable of changing its fate.

Until the very end of the millennium, the vast territories along the riverbanks were excluded from the city fabric. They were perceived as unknown, gated, potentially dangerous lands. There has been no access either from the streets or from the water: private vessels are not allowed in Moscow and the tourist boats sail only in the central part of the historic core, without venturing into the industrial belt. It was only in 2014 that an international competition for the Moskva Riverbanks redevelopment was held and the city authorities and architects finally discovered this forbidden industrial and infrastructural heritage of the city.

Old Structures, New Guises

I began researching the area over a decade ago. At that time I had counted a little over 30 historic industrial sites along the Moskva River within the boundaries of the 1917 official city border: the Kamer-Kollezhsky Val (currently the Third Traffic Ring). A quarter of the factories were in ruins, very few were in operation then and probably none are operational anymore. It was obvious that the bulk of these industrial complexes deserved careful preservation. Well-known architects were involved in their construction. Their spectacular silhouettes, often stylised to look like medieval castles, are capable of becoming new Moscow landmarks. Many former factories have regular layouts and are on a human scale – they look like veritable ‘towns within a town’ with their streets, squares, clock towers and occasional churches.

These European-style brick towns can become the new oases of historical Moscow today.

To attract public attention to these sites, I decided to create an exhibition. After several unsuccessful collaborations with photographers, I met Natalia Melikova, a Moscow-born and San Francisco-educated artist with a great passion for architecture. Her excellent photographs showcased the state of the Moscow riverside factories during the fall of 2013: a valuable spotlight of an infinite change. Working on an exhibition at the Museum of Moscow, as part of a public programme for the Moscow River Development international competition, I could track the fate of the factories I had listed 10 years earlier. A third of them have already been totally demolished to give way to new construction, some were abandoned and others adapted to new life by major redevelopment or temporary use.

Although there is a municipal programme for these former industrial sites, in every case an individual owner, based on his own outlook, chose the strategy. The beginning of the 2000s saw several artistic interventions within the vacant premises, all with different outcomes.

Svyatoslav Ponomarev held his meditative Buddhist style ‘Purba’ performances at the Gustav’s List iron foundry across the river from the Kremlin. The foundry was almost completely demolished overnight for a new unbuilt 5-star hotel – the most expensive wasteland in Moscow is still there. Acclaimed graphic artist Kirill Chelushkin had his workshop at the empty Worsted works on the canal, now destroyed for a Class A business centre. Late curator Olga Lopukhov organised Art-Strelka galleries at the former garages of the ‘Red October’ chocolate factory opposite the Christ the Savior Cathedral.The place became extremely popular and galleries then paved the way for the Strelka Institute for Media, Design and Architecture under the patronage of Rem Koolhaas.

‘Red October’ itself was one of the longest-lived industries in Moscow, pervading the city centre with a chocolate aroma up until 2007. The Guta Development Company then planned to set up loft residences and hotels in eight restored buildings. New structures were to be built as per the winning designs of the closed international contest, in which Ateliers Jean Nouvel, Jean-Michel Wilmotte & Associes, McAdam Architects, Jan Stormer & Partners and others participated. Due to the financial crisis of 2008, Guta decided to postpone the reconstruction and lease the vacated premises. Dutch architect Erick van Egeraat was a consultant with the Guta management and showed them the best practices of European adaptive re-use, saving both the historical site and money. ‘Red October’ became a media cluster and a hub of hipster culture with lifestyle magazines and independent TV headquarters, galleries, restaurants and co-working spaces.

Next to the ‘Red October’ is a 1904 former Central electric tram station. The ‘Victoria – Art of Being Contemporary’ foundation, has recently announced plans to reconstruct it for the Academy of Contemporary Art, a Russian version of the Tate Modern. World-famous architect Renzo Piano has submitted his concept for the project. Other up-scale examples of ‘art-conversion’ usually give impetus to business redevelopment, including such former factories as Golutvinskaya Sloboda, Novospassky and Danilovskaya Manufaktura. In many of them the ‘cultural component’ – museum, gallery or theatre – was purposefully included in the programme to form a multi-functional environment. So-called oligarchs keep an eye on industrial ensembles as a place to keep their art collections. Alexei Ananiev’s Institute of Realist Russian Art was the first to open at the boiler-room of the Cotton Print Factory on Derbenevskaya Embankment (now Novospassky). Then came the Art Deco Museum of the art patron Mkrtich Okroyan at the Friedrich Bayer pharmaceutical factory (Geliimash plant) on the Luzhnetskaya embankment. This tendency shows the magnetising process of the city, discovering ever new treasures within itself: a whole buildup of century-old top-class architecture previously unseen by residents.

Hardly Perfect

Despite this shift from a marginal phenomenon to the trendy mainstream, Moscow’s industrial heritage is still under the threat of destruction.

During the last decade, we witnessed the demolition of the Einem Confectionery printing house and Gustav List’s foundry, the Mettner Lace Factory, most of the Schlichterman soap factory buildings, the Dynamo engineering plant and the gigantic Likhachev automobile factory (ZIL).

The future of several outstanding ensembles is still in limbo. The Badayevsky Brewery, a magnificent castle from the early 20th century was an advanced production unit with the latest technology and faultless work processes. A century later it was scheduled for demolition in favour of a housing development project, which suffered a setback because of the 2008 economic crisis. The current owner is still uncertain about his strategy, letting in multiple temporary tenants from a rooftop bar to the Labirint Pistol Club and Deadrooms quest on the malting floors. Inadequate maintenance is leading to fires and general decay.

All photos: Natalia Melikova

Just across the river, next to the Russian Federal Government building, stands the Krasnaia Presnia Heat and Power Plant. It is one of the finest examples of Russian avant-garde architecture (also known as Constructivism). It looks like a white ship with a tower of spiral stairs inside. It was one of the first facilities built in Moscow under the Soviet GOELRO plan. Electricity production was stopped in 2013 with no future programme for a gated power plant. Collaborating with Narine Tyutcheva, we have developed a concept to turn the former power plant into a Russian avant-garde centre, that would house expositions, art studios, a library, lecture hall, cinemateque, depository and research centre for an estimated 3 million visitors a year. But, unfortunately, the city authorities have shown no interest. The Tashir construction company proposed its own site development project of a high-rise block of flats, for which the plant structures are to be pulled down. Although its cultural heritage status protects the 1928 plant building, it is bound to look like a paper ship against the brand-new gigantic housing.

In Prospect

The rapidly changing political and economic situation in Russia doesn’t assure a prosperous future for its industrial heritage. Developers tend to minimise their investments and put ambitious projects on hold. In some cases it helps to prevent demolition, in others, it leads to further decay.

The rivalry between Moscow City departments further devaluates some obvious achievements. An international competition for the Moskva Riverbanks redevelopment held by the Committee for Architecture and Urban Planning resulted in a comprehensive project including architectural, urban, ecological and social programming issues. Two years later the project was taken over by the Public Works Department and all the plans are now focused on improving the embankment pavement and planting new trees without any understanding of everyday life scenarios. While there is no direct harm done, a great chance to allocate city funds for significant change seems to have been missed.

The historic industrial and infrastructural ensembles on the Moskva Riverbanks and around the city deserve a better fate. Old industries can give place to new creative industries and cultural tourism. The industrial architecture built for ages to come, has a lot to tell about the history of the city. Hopefully this will be understood and promoted on the city and federal level, before it is too late.

All photos: Natalia Melikova

Comments (0)