At a time of increasing environmental concern, the ageless wisdom of vernacular architecture offer us pointers on not only how to rethink built forms and space, but also their relationship with climate and nature. All vernacular architecture is born through a careful understanding of the region’s natural cycles, patterns and phenomena, as well as the easy availability of proximate materials. There are those examples that not only take the architectural processes and forms to unique extremes, but offer deeper reflections and lessons on how architecture can intersect with ecological aspects such as nature regeneration and renewal.

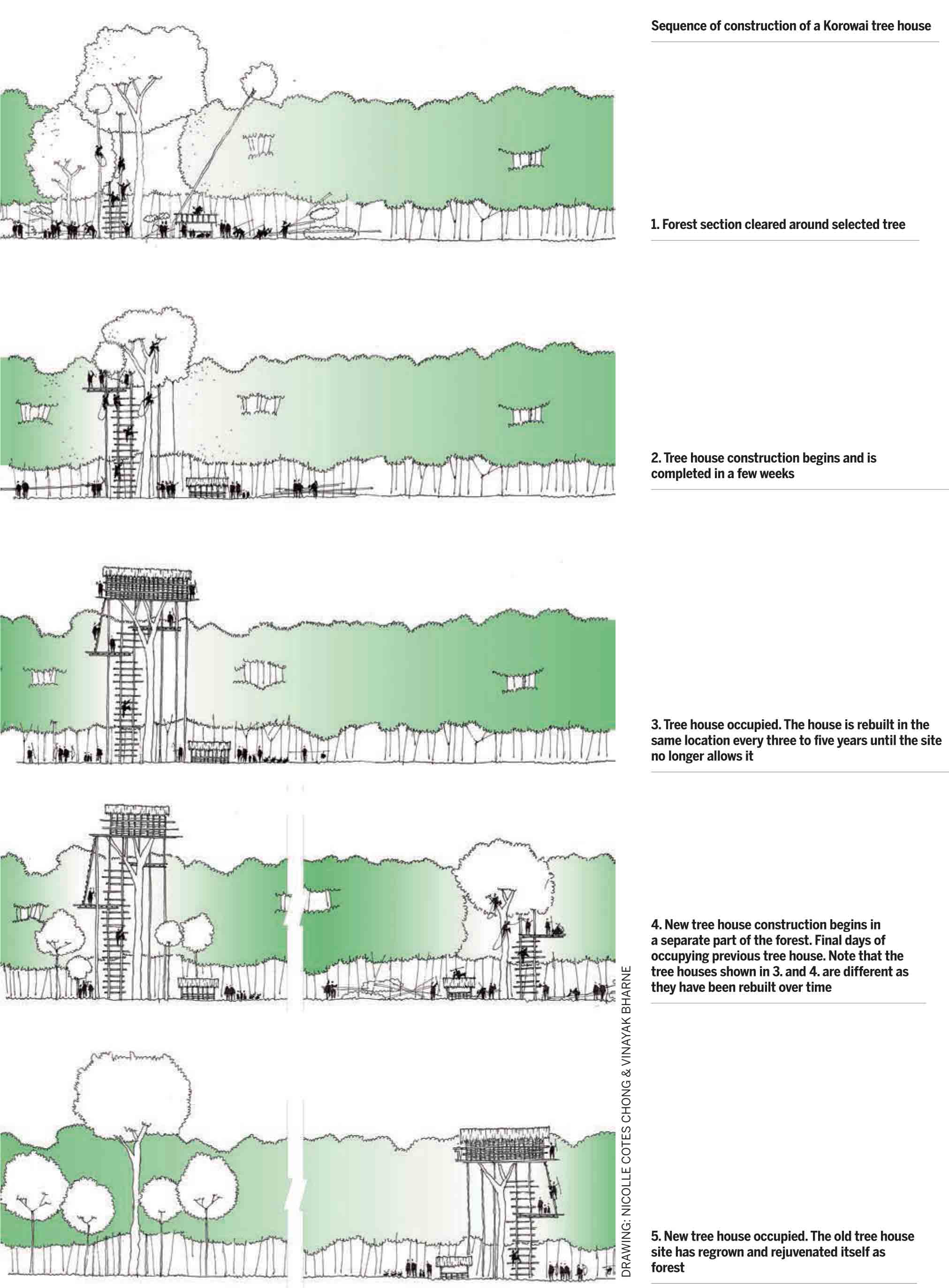

The tree houses of the remote Korowai tribe of West Papua, Indonesia, are a case in point. The Korowai have an estimated population of 4,000 people that exist with relatively little contact beyond their native lands. They stand out in the world of vernacular architecture because their tree houses sit literally atop the earth anywhere from 30 to 120 feet in height. This offers them protection from the threats of the jungle below, while avoiding the seasonal flood waters from nearby rivers. It is also a form of defensive fortification to disrupt rival clans from capturing people for slavery or cannibalism (Stasch). The houses are inhabited by groups of 10 to 20 people for only three to five years, after which a new home is built in the same place on a cyclical basis. When the area can no longer sustain the dwelling’s construction, its location is moved within another jungle territory (Stasch, 2011).

The idea of moving the tree house to a new location is not just a matter of pragmatism and convenience. It is in fact a far deeper ecological endeavour to allow the interrupted forest site to replenish and recover.

It is about ensuring that no permanent and long-term damage is done to any single part of a forest through concentrated development. It is about leaving nature to replenish and renew itself. It is about letting trees grow back and healing parts of a disturbed forest. The lesson of the Korowai tree house is thus as much about dwelling as it is about ecological renewal (Van Enk, 2018).

The construction of a Korowai tree house follows a sequential and logical pattern. Trees are selected as the base or primary support for the dwelling and the area surrounding the selected tree is cleared. Slim support poles are erected to add stability. The construction of the dwelling begins with the floor process because it must be able to endure a load of at least 20 people and also accommodate fire pits. The walls and roof are constructed last, both from parts of the sago palm. To reach the perched structure, tall ladders with notched footholds are built out of a single tree. The entire community is involved in the building process. The lifespan of a tree house acts as a reference for the Korowai calendar, with life cycles measured by the number of inhabited tree dwellings (Stasch, 2011).

West Papua is the second largest tropical rainforest in the world after the Amazon and is currently threatened by rapid deforestation. As of 2016, an estimated 100,000 acres of the original forest have been cut down. These forests not only host the Korowai people, but also nurture a diverse ecosystem that accounts for 7% of the worlds species. They are largely being depleted by logging, occurring illegally in some cases (Garrett, 2018).

The wasteful method of burning used to clear the land for logging, coupled with the rapid deforestation rate, makes it difficult for a forest area to regenerate. This is antithetical to forest regeneration, a practice the Korowai are deeply familiar with. The deforestation rate is also drastically impacting the Korowai people: Logging industries are creating waste and polluting the same rivers that the Korowai inhabit and depend on. Habitat loss creates a loss of basic resources for the Korowai, mainly food and shelter. Their land rights are taken advantage of by the logging companies that have established themselves in the region and, despite a rising group of activists, the Korowai are effectively voiceless in this land epidemic (Bryan, 2014; Gabbatiss, 2018).

As of 2017, the Papua New Guinea Forest Authority (PNGFA) has made significant improvements with how it monitors its forests. Following an agreement between the Papua New Guinea government and the United Nations, the PNGFA is currently working in partnership with the United Nations REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries) National Program and National Forest Inventory Project. However, the issue of illegal logging practices still proves resilient.

Numerous vernacular habitats across the world suffer from the onslaught of such destructive environmental practices. While some like the Korowai are now beginning to gain attention – thanks to recent documentaries and articles – many yet remain relatively invisible to the mainstream eye. The intention of writing this essay is to call for deeper reflection and urgent action towards the strategic conservation of such ingenious communities in a rapidly urbanising world that appears to increasingly ignore the timeless cultural and ecological heritage at stake here.

REFERENCES:

• Paul Raffaele, “Sleeping with Cannibals,” Smithsonian.com, September 01, 2006

• Rupert Stasch. “Korowai Treehouses and the Everyday Representation of Time, Belonging, and Death.” The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology 12, no. 4 (2011): 327-47.

• Gerrit J. Van Enk and Lourens De Vires, “The Korowai of Irian Jaya : Their Language in Its Cultural Context,” Find in a Library with WorldCat, March 10, 2018,

• Jemima Garrett “Losing Papua New Guinea’s Rainforest.” ABC News. March 10, 2016. Accessed April 2018.

• Jane E. Bryan, “The State of the Forests of Papua New Guinea 2014 : Measuring Change over the Period 2002-2014 / Jane E. Bryan, Phil L. Shearman (eds) - Version Details,” Trove, 2018.

• Josh Gabbatiss Science Correspondent, “Alarming Photos Reveal Devastating Scale of Rainforest Destruction in Papua New Guinea,” The Independent, March 21, 2018, accessed April 2018.

Comments (0)