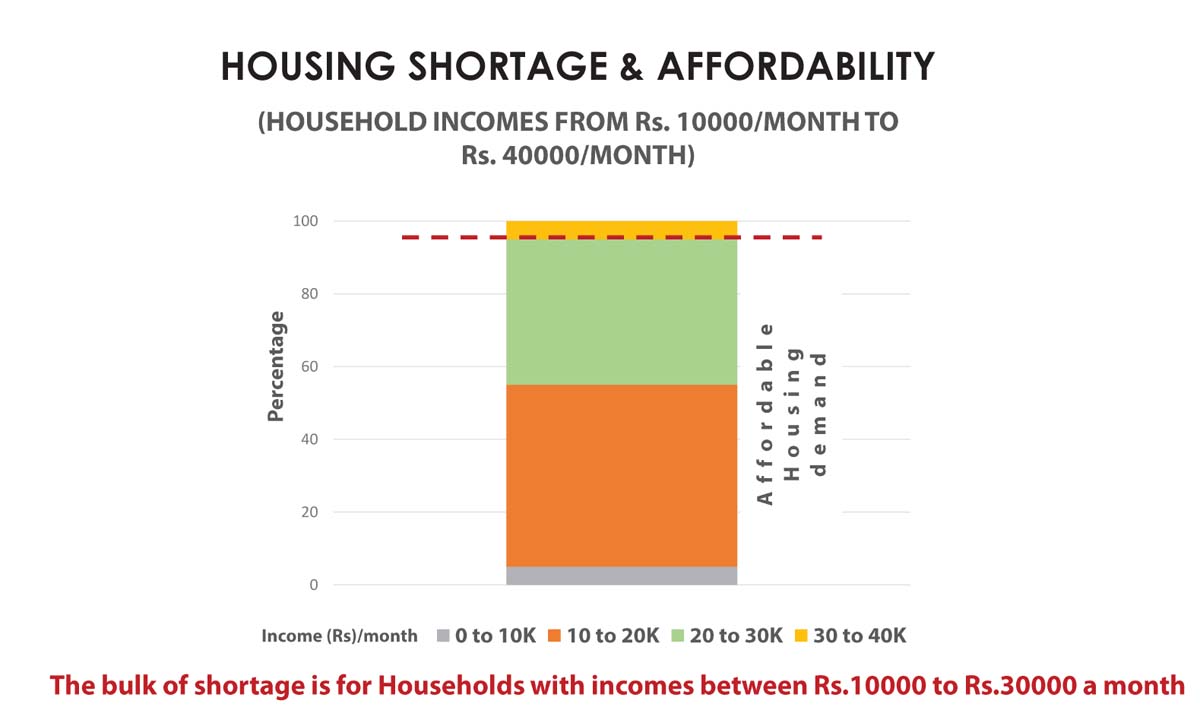

The numbers put out by Niti Aayog, the present policy think tank for the Government of India, make it abundantly clear that the ‘shortfall’ of housing in cities is principally for those households who are at the bottom of the income pyramid. This constitutes about 60% of the population of cities. The shortfall, though, includes those existing homesteads where people are living at present, but which are considered to be unsafe and unhealthy for habitation i.e. slums, buildings and neighbourhoods that need to be upgraded, redeveloped or relocated.

Although slums persist in many of our cities today and much of the policy space is consumed by the idea of slum eradication and slum clearance as post facto corrective measures, the discussion is about the prospective possibilities of housing policy and housing design, where slums do not occur any more.

Given that the provision of housing will, inevitably, follow three streams – a) self-build small-scale construction, b) medium scale low rise, high density construction in suburban areas and cities and, c) large projects by big players – diverse strategies according to the particularities of each of the three streams are called for. The common issue is that of land: its location, its availability and its utilisation.

Spatial Equity and Land Equity

The economic shifts toward urbanisation signal an opportunity for the processes of urban growth to be designed for distribution of wealth. Affordable homes for the majority of citizens that are legally secure, structurally and environmentally safe, located close to opportunities for employment and trade, with access to educational and health services, are at the centre of such a strategy.

This objective calls for spatial equity, land equity and parcels to be reserved for homes so that one can stay close to work and to income opportunity, which means spatial equity. And land prices would be sheltered from the deleterious effects of land speculation, so that an affordable home is within reach. This is land equity.

Land

Let us be clear about one thing, that the speculative markets of private lands and the State’s penchant to ride such speculation, to capitalise on the market value of land as a revenue source, have had the opposite effect. ‘Market based solutions’: solutions that are driven by the current unregulated speculation on land and an artificially created scarcity of land have been the cause of greater spatial inequity and land inequity. If one has poor earnings one must live further away and commute further, for it is only at the great distance from the economic heart of the city that land is affordable. A good one third of one’s energy and earnings are dissipated on burning fuel and time in travel. No wonder the resultant is slums and unauthorised habitation in the interstices of the city.

Singapore’s success

The success of Singapore’s Government in providing affordable, quality homes to about 80% of its population through its Housing Development Board (HDB) is instructive. Through farsighted legislative and fiscal measures large tracts of land were reserved for affordable housing and taken out of speculative land markets. The cost of land, being freed of speculative markets, became affordable for the state and the homebuyer. The monetization of land as revenue for the urban development authority was done judiciously, for selected downtown sites and new reclaimed land from the sea, in a manner that did not cause speculative landholding. In sum, the priority of the island nation’s land policy was to secure affordable homes for its citizens. It was necessary to regulate the land market to meet the legitimate needs of its citizens for affordable homes. It is now established that in emerging economies, where land markets are not mature and tend to be distorted, ‘housing for all’ requires a strong land regulation and land release policy.

Social Housing in the Netherlands

Let’s take a brief look at the success of the social housing programme of the Netherlands. This little nation has 350 non-profit Social Housing Corporations who finance housing for those at the bottom of the economic pyramid. Such corporations provide 45% of the housing stock of Amsterdam. Once again, the essential feature of affordability is that the land allocated to social housing is priced at 1/3rd of the open market price. All homes are leasehold or rental. Private area-developer projects (townships or neighbourhoods) are, by law, required to reserve 33% of the land for social housing in partnership with the Housing Corporations. Typically, in land-short Netherlands, housing is low rise up to four stories high. The principle is twofold: to keep the city really compact with a comforting, active, humane network of streets, squares and gardens which are inhabited by people, and to reduce the distinctions and spatial segregation between classes and communities.

The high Floor Space Index (FSI) folly

A myth is being perpetuated that land is expensive and in short supply. On the basis of this assumption, city planning authorities are raising permissible FSI to accommodate the anticipated demand – not only in the large metros, but also in satellite towns and tier two and tier three cities. It is said that increasing FSI reduces the proportionate cost of land on each dwelling unit and thereby makes access to housing more affordable.

‘Going vertical’ to house more people is deemed to be the automatic and inevitable result of land shortage and land cost. In this arithmetic the permitted FSI keeps climbing from 2.5 – which calls for buildings that are about eight-storeys tall – to 4 resulting in buildings more than 16-storeys high.

Now, we have seen that across most cities in India raising the FSI has not resulted in bringing down the cost of buying a home. It has, on the contrary, raised the cost of land in proportion to the amount of building you are allowed to pile on it. The higher the permitted FSI the higher the market price of land. Higher FSI does not make homes more affordable if the land price is not kept down.

Furthermore, taller buildings are more costly to build, take longer to build and require more capital to undertake projects. It is no surprise that huge numbers of multistorey housing towers are lying incomplete today, with developers becoming insolvent and so much steel an cement hanging up in the air as locked, unproductive national wealth. Even when cross-subsidised, as in the Slum Redevelopment Authority projects of Mumbai, they are woefully inappropriate for tiny homes for people with meagre incomes. This lesson has been learnt.

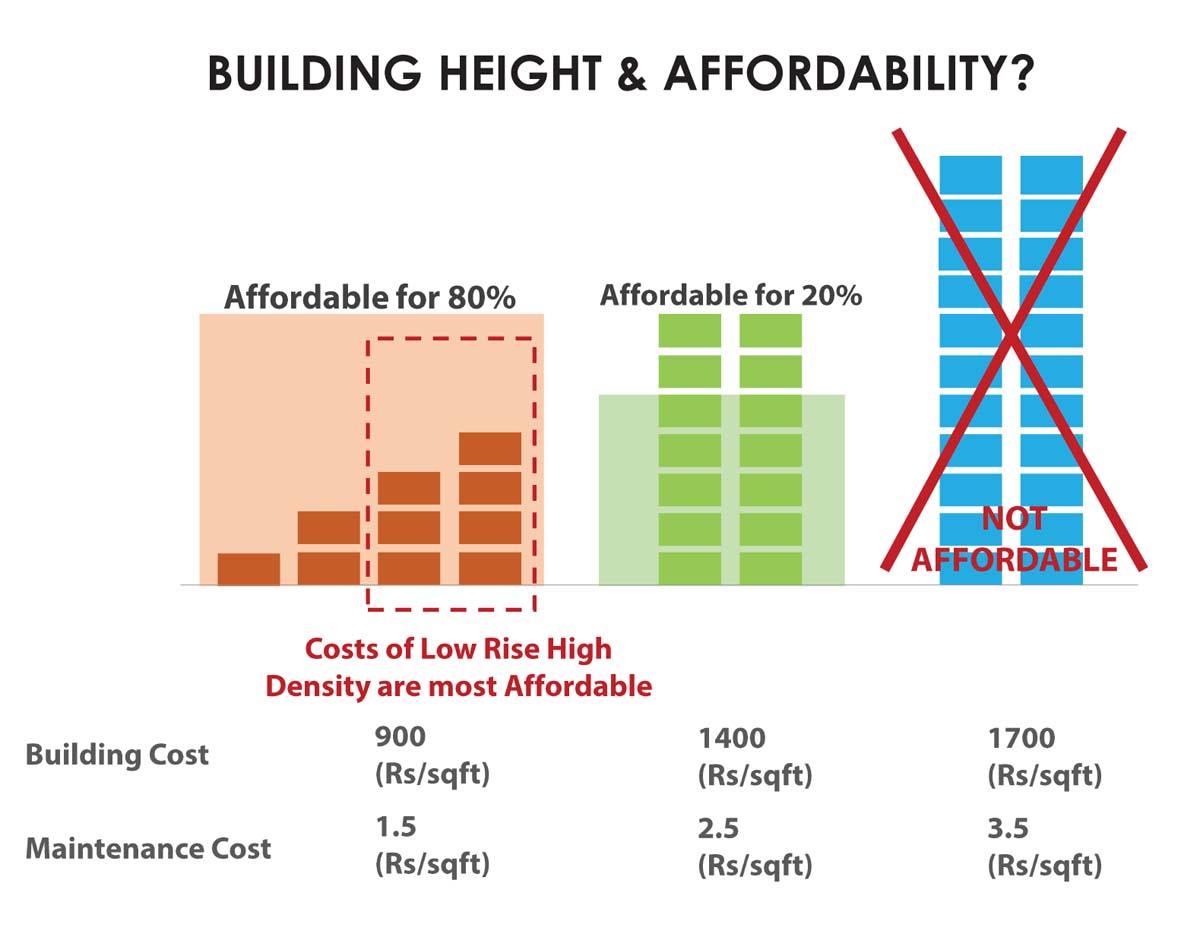

High-rise means high lifetime cost

Our research on construction costs shows that construction costs and building operation costs rise by 15% for every six storeys increase in height. The maintenance costs for the lifecycle of tall buildings, with their dependence on elaborate electro-mechanical systems for vertical transportation of people, goods and water and safety against fire, and their exposure to weathering and vibrations, are 20% higher than costs for four-storey buildings. Affordability is not just about building construction costs, but needs to be ensured through the life of the building. As these homes are occupied, people should be able to afford their maintenance and running costs. If we are talking of affordability at our present levels of income, for 60% of our households with income below Rs. 3000 per month, we must chose to build low rise, the more economical way of living in buildings.

Task for the designers of the Built Environment

Housing environments – places for all those who would live their lives there including children, youth and the elderly – do not drop out of arithmetic formulae. It seems that many ‘stakeholders’ like administrators, political bosses, financiers and bankers, municipalities, city development authorities and even speculative developers are unable to see anything beyond the quantities of floor area stacked up on some land like gunny bags full of potatoes. They tend to restrict the role of the designer, apart from her primary one of ‘tarting up the elevation’ to the reduction of costs of construction and to driving floor area efficiencies.

When we talk of the challenge of affordable housing we refer to the less well off 60% of our urban population. The living condition of this 60% is what constitutes ‘the quality of life of a city’. The challenge of planning and design is to develop liveable urban morphologies and building types in ways that work at the present economic threshold of affordability for the 60% and yet provide the foundation for progressively raising standards of living and improving and enriching their quality of life. Research and innovation is needed to find the answers to this objective.

Robustness of housing typologies

Households are not a standard or a static entity. A bunch of college students can be a household; friends or cousins can be a household. Even in a typical nuclear family there will be changes over time: the young couple, with young children, their grandparents may come to stay, the children grow up, some of them leave for studies, then the son brings a bride and grandparents may have passed away. Then comes a time when it may be advantageous to rent out a room. Or one might be working from home. Confined small spaces cannot be cast in concrete forever.

For optimum service and use of the small home over its 60 years of useful life, building design must promote ways of adjusting the inside arrangement of the home.

And we do expect that life will get better for everyone after they move into their home. The safe, comfortable home is that essential support that enables people to devote their energies to build a better future. Some residents will move on to better places elsewhere. Others will want to enlarge their homes by buying from their adjacent neighbours. Designing for these changes and transformations over time makes sense. It means that the basic structure of the building remains useful for a long time.

|  |

European experience

The brick wall row housing of Europe that was built in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with a semi basement, three floors and an attic, has proved to be a truly robust solution. They are still there, adapted and modified to meet the changing needs of changing times all made possible because the structural chassis of the buildings enables change without wholesale demolition. This is strategic design for long-term robustness and sustainability.

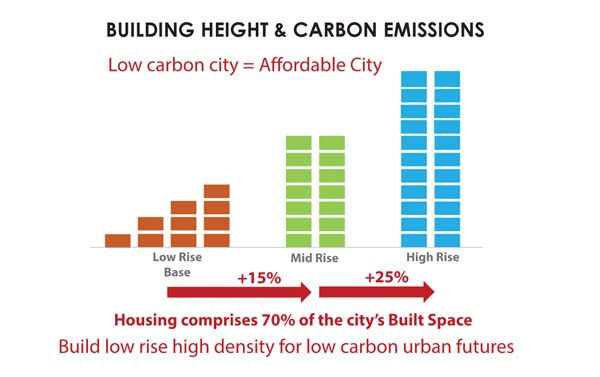

Contrast this with the all RCC formula gaining popularity today – all walls, internal as well as external, will be cast-in-situ RCC – in the name of economy. This is fossilising the home, fixing it forever with no possibility of adaptation or alteration. The worst kind of homes, from a standpoint of environmental sustainability, that you can build today are high-rise, all RCC towers. Empirical research shows that the lifetime carbon emissions of 12 storey, all RCC buildings work out to be 30% higher per unit of floor area built compared to a 4-storey row housing of RCC frame with flyash or lightweight concrete block masonry. The culprits, as you build taller and taller, are: the increased dependence on steel with its high-embodied energy and the operational energy of lifts and pumps.

Resilience

Answer this simple question. Which of the two kinds of buildings are you safer in when there is power grid or infrastructure breakdown, an earthquake, a fire or an explosion: the 20-storey tower or the walk-up four storey apartment? The city must choose a way of building homes that is inherently resilient and not dependent on layers and layers of complicated technologies to enable day-to-day living. Resilience of simple self-sustaining systems is a long term insurance policy.

Solar Cities

‘Solar Cities ho!’ If anyone is serious about this potential for leapfrogging into a low carbon urban life, with the promise of reversing climate change the answer is roof top solar PV (photo voltaic) over four or five storey high buildings. Thanks to plentiful sunshine across the Indian subcontinent approximately 80% of the annual electricity requirement of simple (non air-conditioned) homes can be met by roof top installation for the four or five storeys of homes below those roofs. As you build taller this ratio declines. The taller you build the worse it gets. The Solar Cities dream becomes fiction in a high-rise city.

Silver lining

But there is a silver lining. Let us look at two recent awards for affordable housing:

HUDCO Design Award 2016, First Prize: Affordable Housing for Rajkot Municipal Corporation, Architect: Parag & Mona Udani. NDTV Parryware Award for best Affordable Housing project 2106 - by Happinest Mahindra Lifespaces at Chennai. Architect: Ashok B. Lall Architects.

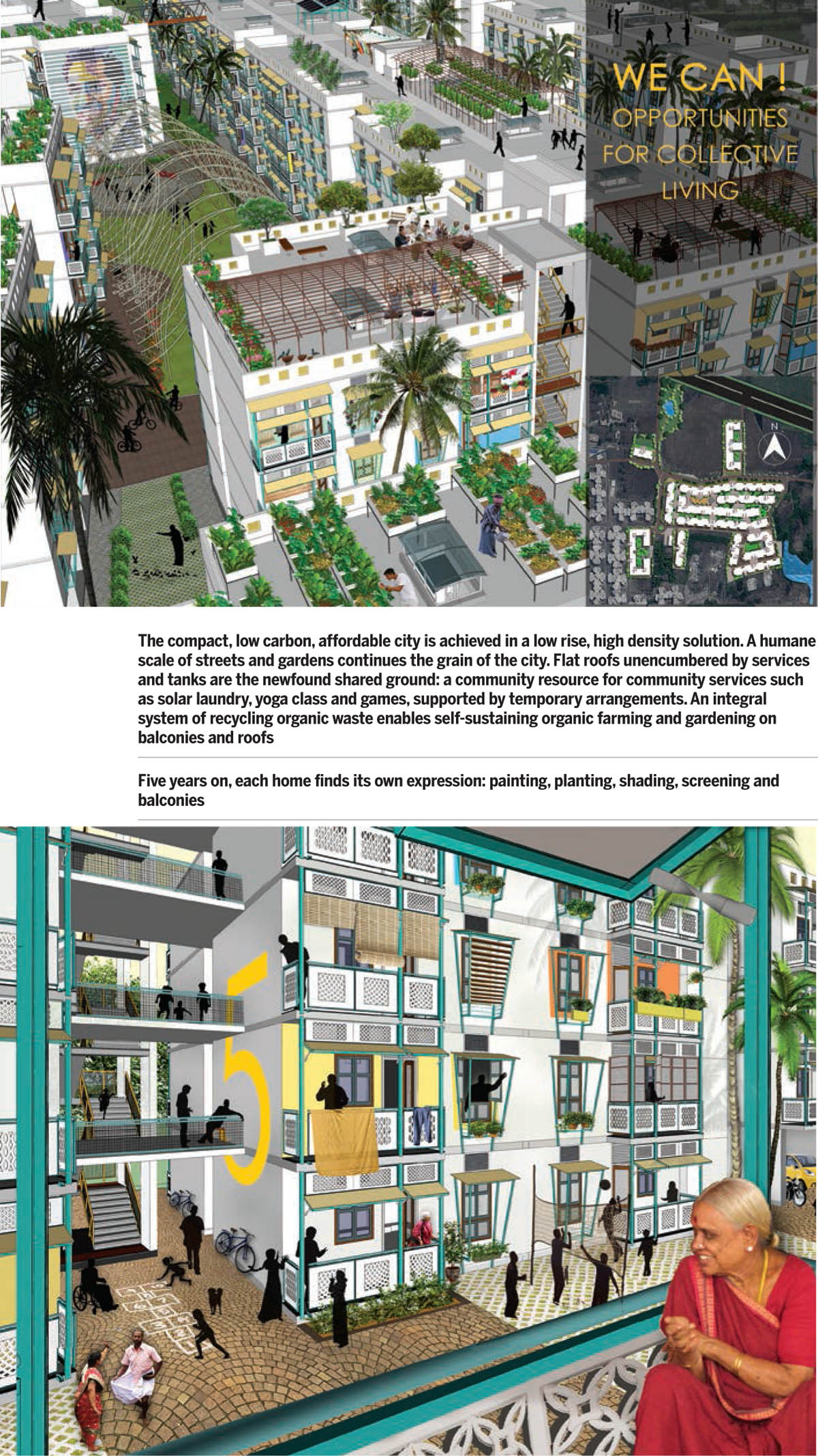

These are awards that give due recognition to the Opportunities of Collective Living – of the enhancement of the home as an active participant in the making of collective well-being. Balconies, terraces courts, the shared street courts and the identity of each home marking its unique presence. And most importantly, they demonstrate the value of human scale and variation of space and arrangement, which create an outdoor environment where residents find ‘comfort and security’ amongst their neighbours as their homes gather around and look onto the street and the court. Where homes are small, less than 50 square metres in area, and at least half the population is below the age of fifteen, there is need for ‘habitable’ common spaces adjacent or near the home.

At an FSI of 1.5, residential densities of 1000 persons per hectare (and higher) are achieved with low-rise buildings. This is a land conserving, affordable, culturally and socially appropriate solution for the great majority of cities in India undergoing rapid urban growth and regeneration.

Imagine

Imagine a compact city of streets and squares, quiet, safe, unpolluted, trees, birds and shaded walks with convenient connectivity to rapid transport to places that are beyond walking or cycling distance, rather than a city that has been sacrificed to the motor car; a city of small build buildings, with plenty of variety; a robust city fabric which has the ability to change and renew itself continually without the trauma of the demolition of the four-storey podium surmounted by 20-storey towers. Imagine a city in whose making and renewal, small and medium size entrepreneurs are able to participate rather than being produced by the heavy repetitive stamp of the big developer; a city whose roofs are places of recreation – flying kites, skating, yoga, dance – and of production: electricity from the sun, vegetables, herbs, solar kitchens and solar laundries. A city with the DNA of long-term sustainability where knowledge and wealth are distributed as the mechanism for its sustenance. This is a city of the 60% first.

Comments (0)