The challenges of our rapidly urbanising cities require us to take a step back and evaluate specific areas that need calibration - the lack of ‘housing for all’ emerges as one of the primary needs. Recognising this lacuna, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 11 brought forth the importance of making all settlements “inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable”. Building on this, in 2016, UN Habitat’s ‘Housing at the Centre’ sought to view housing not just as a place for inhabitation but as a fundamental right to live with security, dignity and peace. For Persons with Disabilities (PwDs), this fundamental right to adequate housing is often largely disregarded and thus compromised.

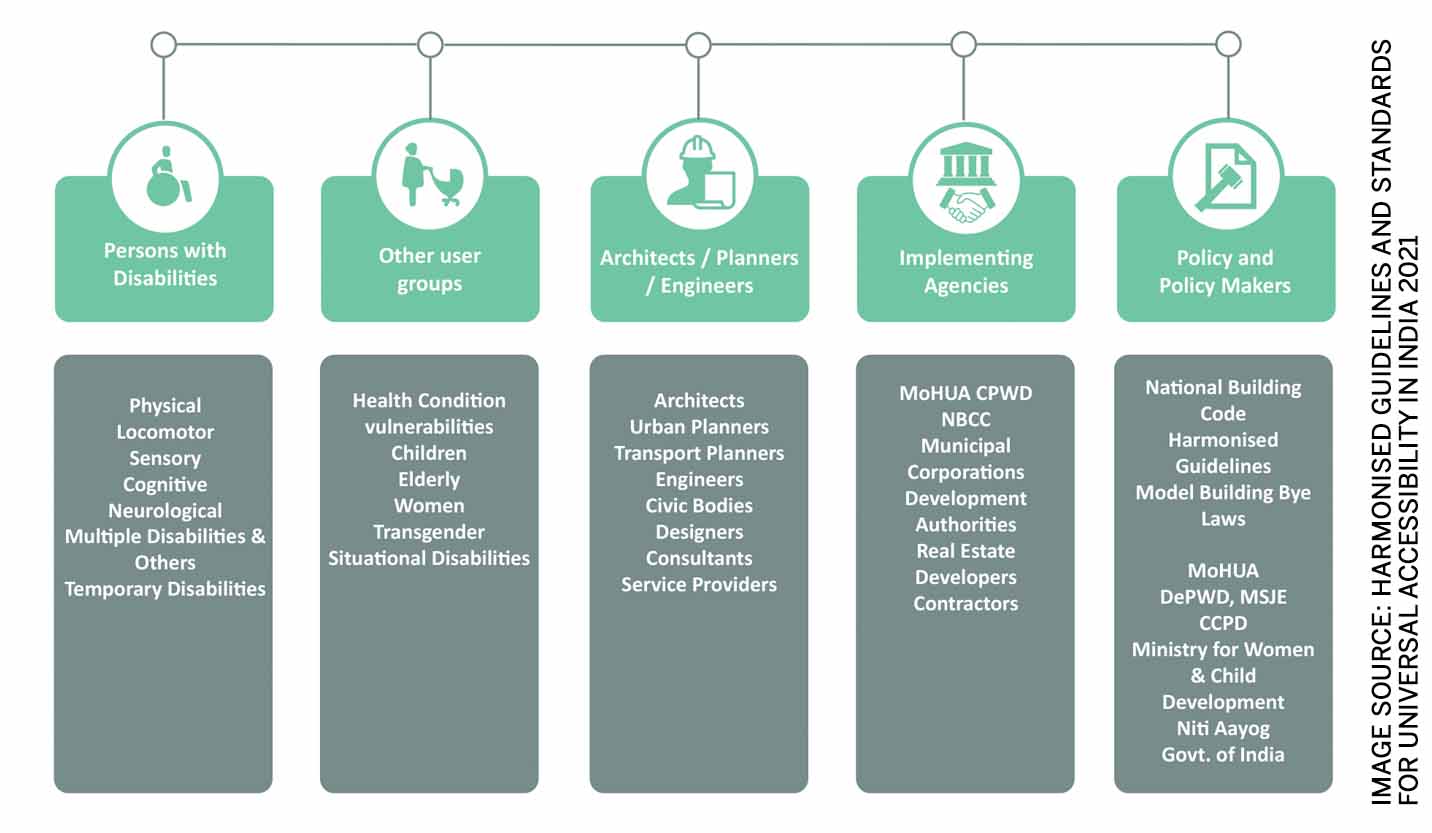

In India, nearly 2.21% out of a 121 crore population have a disability, which is almost 2.68 crore persons, as per the disability status in the Census 2011. Yet, we see only one-size-fits-all housing models in our cities without consideration for basic accessible infrastructure for persons with disabilities. To overcome this impediment, the RPWD Act 2016- sections 40 and 44, underscored the legal mandate of providing universally accessible infrastructure to persons with disabilities, which meant that new constructions without accessible infrastructure are liable to be penalised. In response to these policies, Inclusive housing as a typology must be viewed as a combination of Universal Design, specific adaptations and assistive devices for particular user groups with disabilities where needed.

- Steinfeld and Maisel, 2012 |

For Persons with Disabilities (PwDs), lack of basic access to spaces strips away the right to social participation, and the ability to lead wholesome, independent lives that so many of us able-bodied individuals take for granted. To aid individuals and organisations, the Harmonised Guidelines 2021 was published by the Ministry of Urban Affairs, Govt. of India, which is a recommended set of Universal Design standards for designing inclusive built environments.

Even if there is a long way to go in terms of achieving holistic models of inclusive living on the ground, there are efforts in this direction that organisations are taking, through different approaches. Through this article, we wanted to highlight a few endeavours to help inspire cumulative action towards making inclusive housing a reality in Indian cities.

Approach 1: Home modifications as a means to mainstreaming inclusive living

Vidya Sagar, in Chennai, an organisation that empowers individuals with disabilities through comprehensive services, acts as an advocate and enabler in creating barrier-free living spaces. The organisation strongly believes in integrating support services along with accessible infrastructure through detailed access audits. These are aimed at addressing the socio-cultural, physical and cognitive needs of the user, to elevate their level of independence in living environments. Their initiative, BLISS (Begin to Live Interdependently with Support Systems) was conceived as a response to growing concerns of parents of children with disabilities about uncertainties surrounding their child’s foreseeable future.

Accessibility Coordinator at Vidya Sagar, Architect Shivani Shah points out that the stigma linked to disability originates from a lack of awareness about the nature of disabilities. Often misconceptions lead to attitudinal barriers making it difficult for PwDs to find reasonable accommodation to rent or purchase. This is aside from the fact that most housing complexes are physically inaccessible to people with disabilities with little to no interventions for seamless access.

|

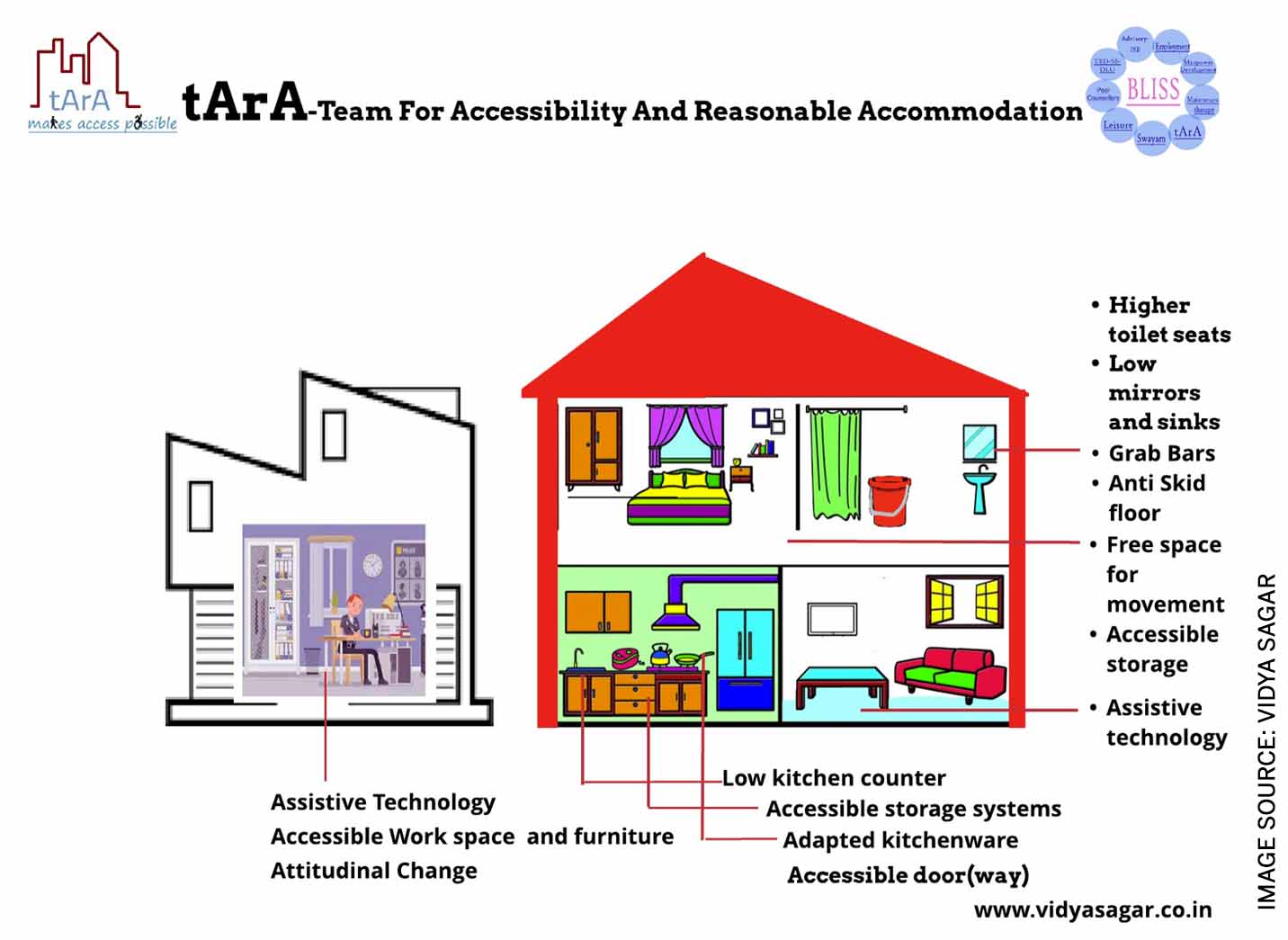

To help overcome these obstacles, under the BLISS initiative, TARA (Team for Accessibility and Reasonable Accommodation) was set up to create support systems by way of self-help groups, and awareness generation models like a demonstration centre showcasing an inventory of assistive devices for PwDs. Among infrastructure, they connect PwDs with accessible transport services and enable home and workplace modifications to provide access.

The team involved in the design of these accessible spaces comprises a multi-disciplinary mix of professionals to best understand the users’ needs- who are often non-verbal. The diverse team that is adept at bringing case-specific solutions, comprises a counsellor, a physiotherapist, a doctor or teacher who is familiar with the background of the PwD, and an architect. The team undergoes a three-month-long intensive training program that involves understanding disability, and barriers faced by the PwD, managing interpersonal dynamics, and modifying processes to create accessible spaces.

In India, nearly 2.21% out of a 121 Cr population have a disability, which is almost 2.68 Cr persons, as per the disability status in the Census 2011. Yet, we see only one-size-fits-all housing models in our cities without consideration for basic accessible infrastructure for persons with disabilities.

Top Left: Accessible Rest-Room

Top Right: Accessible Kitchen

Bottom Left: Accessible Bedroom Space

Bottom Right: Accessible Wardrobe

Apart from retrofitting projects, the team strives to spread awareness about accessibility. Working with the Tamil Nadu government TARA has been instrumental in developing a prototype of an accessible home for PwDs which is now converted to a permanent exhibition - The Museum of Possibilities, at Triplicane, Chennai. This model house comprises a living, kitchen, and bedroom, equipped with automated services, adjustable storage and working surfaces for wheelchair access, accessible bathrooms with grab bars and many other assistive interventions.

The museum’s goal is to showcase the latest assistive aids and devices, and technological advancements catering to the disabled community. The assistive devices are arranged according to the Live-Work-Play module on a wall-mounted unit with cubicles- housing up to two hundred and fifty devices for varying purposes including board games with braille prints and medical devices with auditory output. The prototype of this accessible home becomes a model that could be replicated and adapted at larger scales.

For Persons with Disabilities (PwDs), lack of basic access to spaces strips away the right to social participation, and the ability to lead wholesome, independent lives that so many of us able-bodied individuals take for granted.

https://www.jtech360.com/CL/ksmedia1/vtour/tour.html

Approach 2: Assisted Living facilities with symbiotic community relationships

One of the models that have seen some traction is Assisted Living facilities set up by parent-driven organisations working towards providing nurturing environments for Persons with Disabilities (PwDs). ANANDA, in the outskirts of Gurgaon, is one such facility set up by Action for Autism, that prioritises the well-being and independent functioning of individuals with Autism. The campus was established in 2020 and has been growing incrementally ever since.

The premises integrate housing blocks, a vocational centre, and healthcare facilities within a single campus. A housing facility accommodates a mix of individuals with developmental disabilities along with trained support staff or “Assists”, enabling a supportive community. The vocational centre or workspace, within walking distance, is a space to engage residents in various activities, like craft and jewellery making and creative packaging. This, apart from providing a sense of purpose, also becomes a means of income generation through skill development.

Right: Inside the vocational centre.

At the heart of ANANDA’s philosophy is the belief in treating residents and assists, as equals, eliminating hierarchies that may compromise dignity. This ethos permeates the entire facility, ensuring a healthy social environment that empowers residents to make choices within a structured routine. The design and functioning of the living spaces have been a work in progress. Merry Barua, director of Action for Autism reflects on how the running of the campus is a constant process of learning and unlearning. Lessons from the first housing block have informed the design of subsequent blocks. Attention to detail, for instance, in design has been paramount in ensuring that the sensory needs of residents are addressed. Some details included smaller bedroom sizes for a feeling of comfort and reduced anxiety, concealed services and avoidance of hanging lights to ensure safety during potential triggering episodes. Quiet rooms are attached to the larger living area and act as spaces to retire to for those who are hypersensitive to noise and volume.

Working with the Tamil Nadu government TARA has been instrumental in developing a prototype of an accessible home for PwDs which is now converted to a permanent exhibition - The Museum of Possibilities, at Triplicane, Chennai.

Right: One of the bedroom units (single occupancy)

The facility incorporates a resource room with visual aids, acknowledging the importance of non-verbal communication for many residents. Landscaping is kept natural, with a focus on sustainability through permaculture, where vegetables are grown organically to be used in the food prepared for everyone at the facility. A part of the produce is sold to the local markets to serve as a potential source of income.

Right: Organic vegetables grown in the open spaces using permaculture.

While prima facie, many may view the facility as exclusive, the model does attempt to integrate the campus and residents with the surrounding rural context to ensure community engagement. Residents participate in walks and treks around the villages, fostering familiarity and acceptance within the local community. The facility’s health centre provides medical assistance to villagers, creating a mutually beneficial relationship. Importantly, ANANDA goes beyond just providing a living facility; it actively works towards fostering more independence among residents. Some individuals through time have even transitioned to be able to commute to the city for work while continuing to reside in the premises, showcasing the success of their support systems.

At the heart of ANANDA’s philosophy is the belief in treating residents and assists, as equals, eliminating hierarchies that may compromise dignity. This ethos permeates the entire facility, ensuring a healthy social environment that empowers residents to make choices within a structured routine.

Approach 3: Architects as enablers, with inclusivity as a design ethos

After understanding organisations’ perspectives and roles, there is a need to reflect on the responsibility of designers in envisioning and executing inclusive housing modalities. 369 Ochre Studio, an architectural practice based in Bangalore, co-founded by architects Bhagyalaxmi Madapur and Shreya Shetty, was established with Universal Design and Inclusivity as a core principle. The team imparts consistent efforts through their project proposals, stakeholder interactions, and capacity-building workshops to spread awareness of the importance of Universal Accessibility as an enabler in the urban and architectural realm.

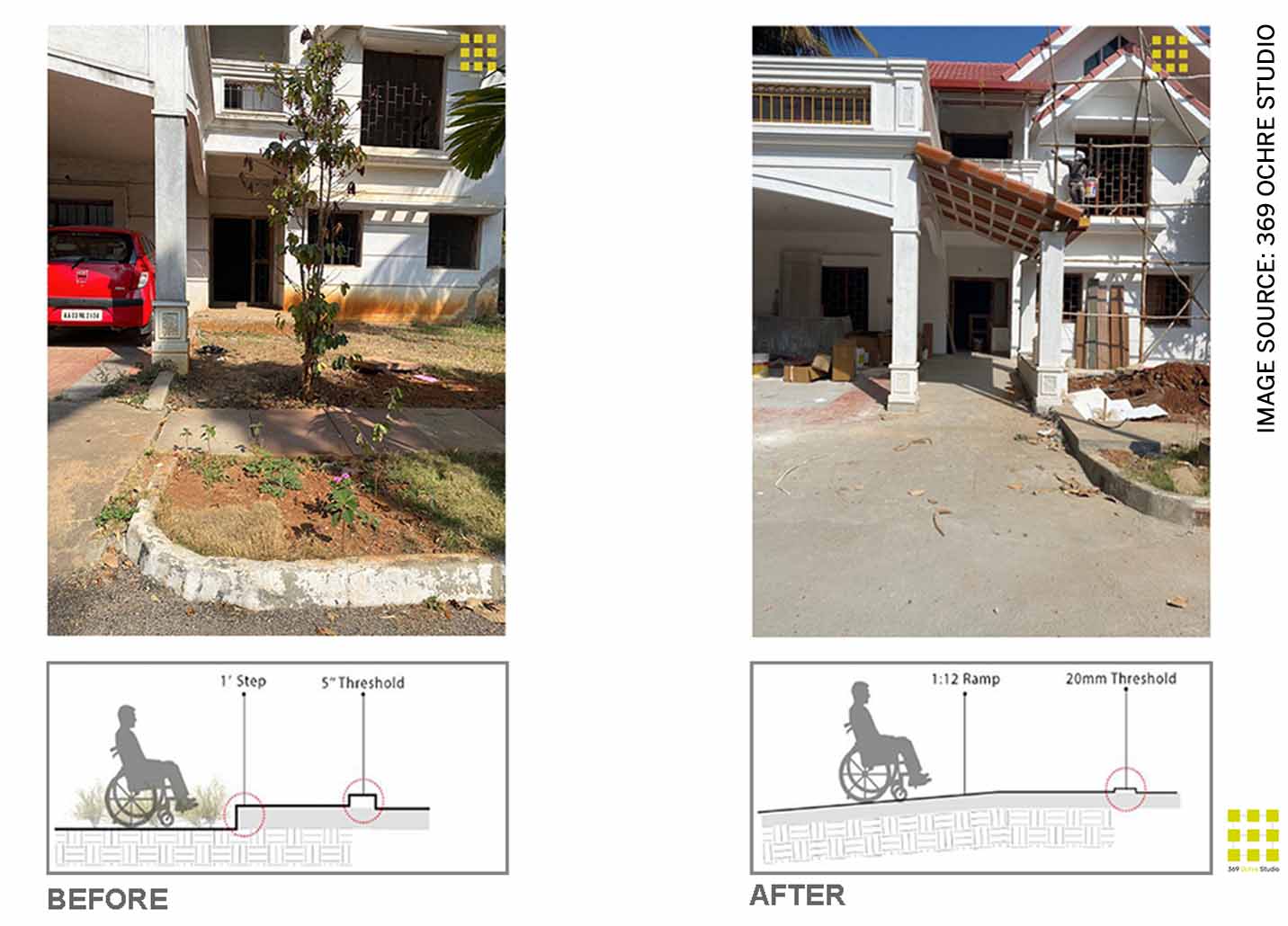

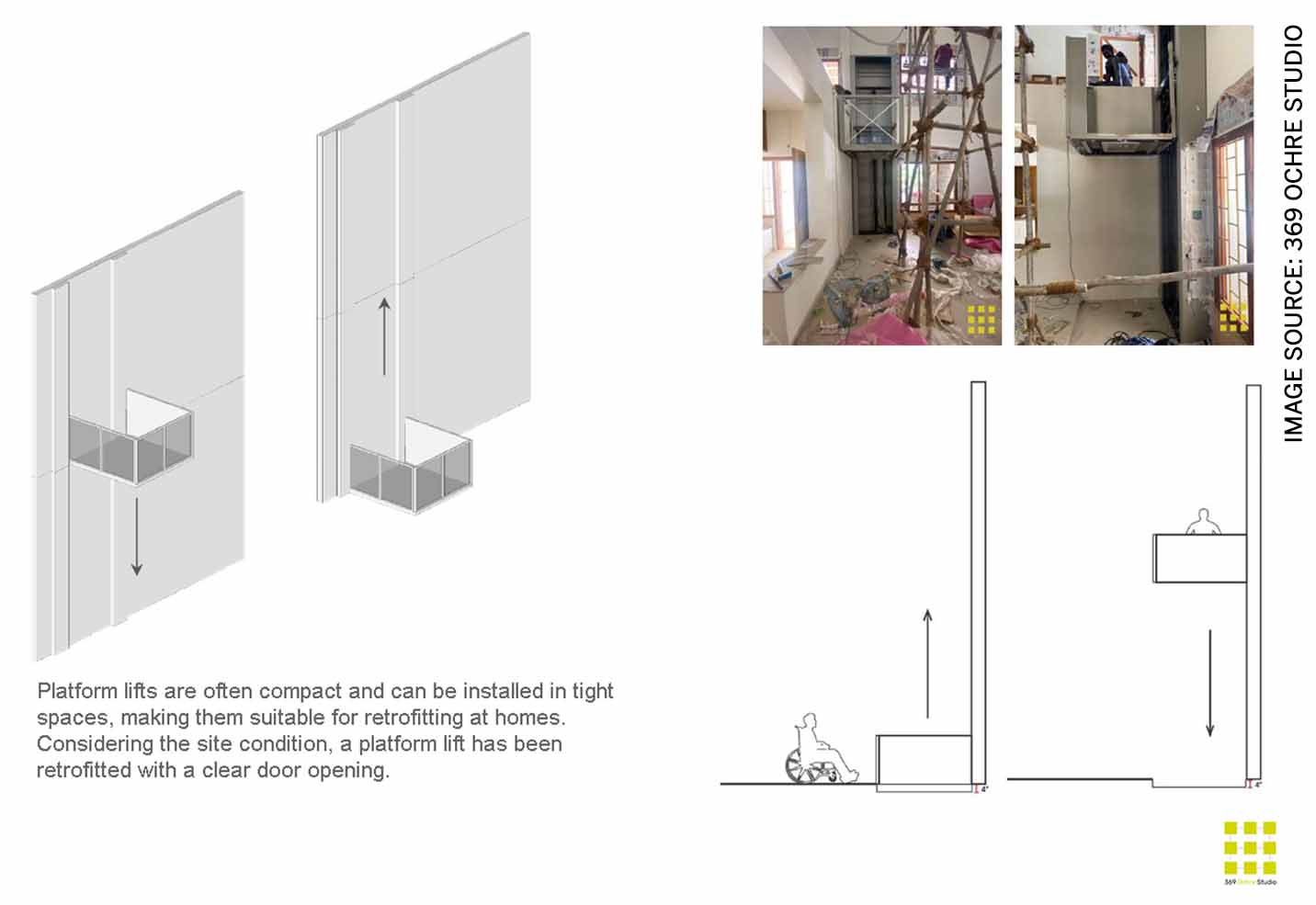

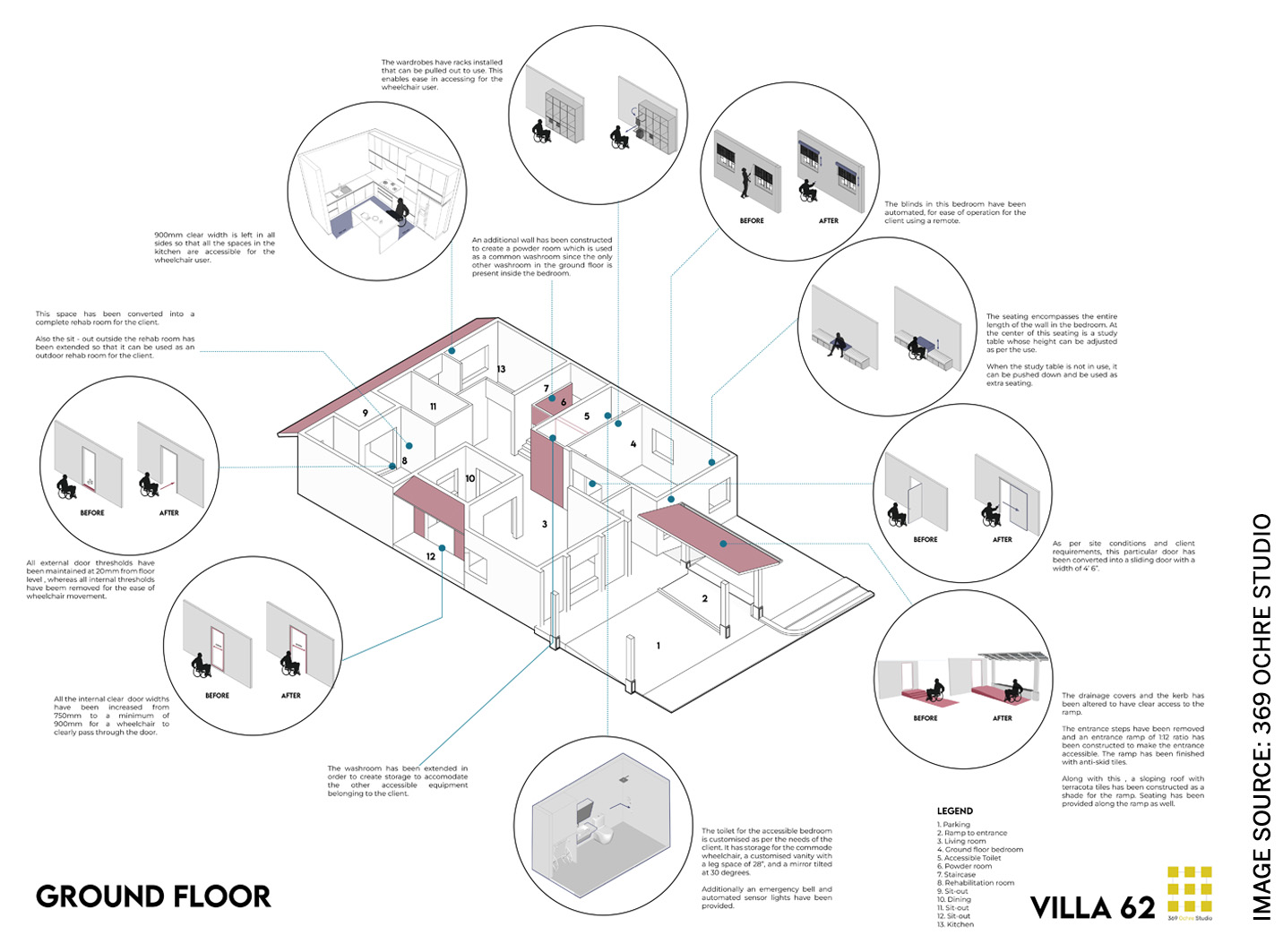

One of their projects that focuses on inclusive living, is Villa-62, a bungalow that was designed with customized accessibility interventions based on the specific needs of the client. The villa that already had the structural frame in place, had to be retrofitted to meet the requirements of the primary users- a son- a wheelchair user with sensory-motor neuropathy, and his elderly parents, along with other family members, caregivers, and domestic help. The team collaborated closely with rehabilitation specialists and doctors to integrate accessibility requirements into the retrofitting plans.

|

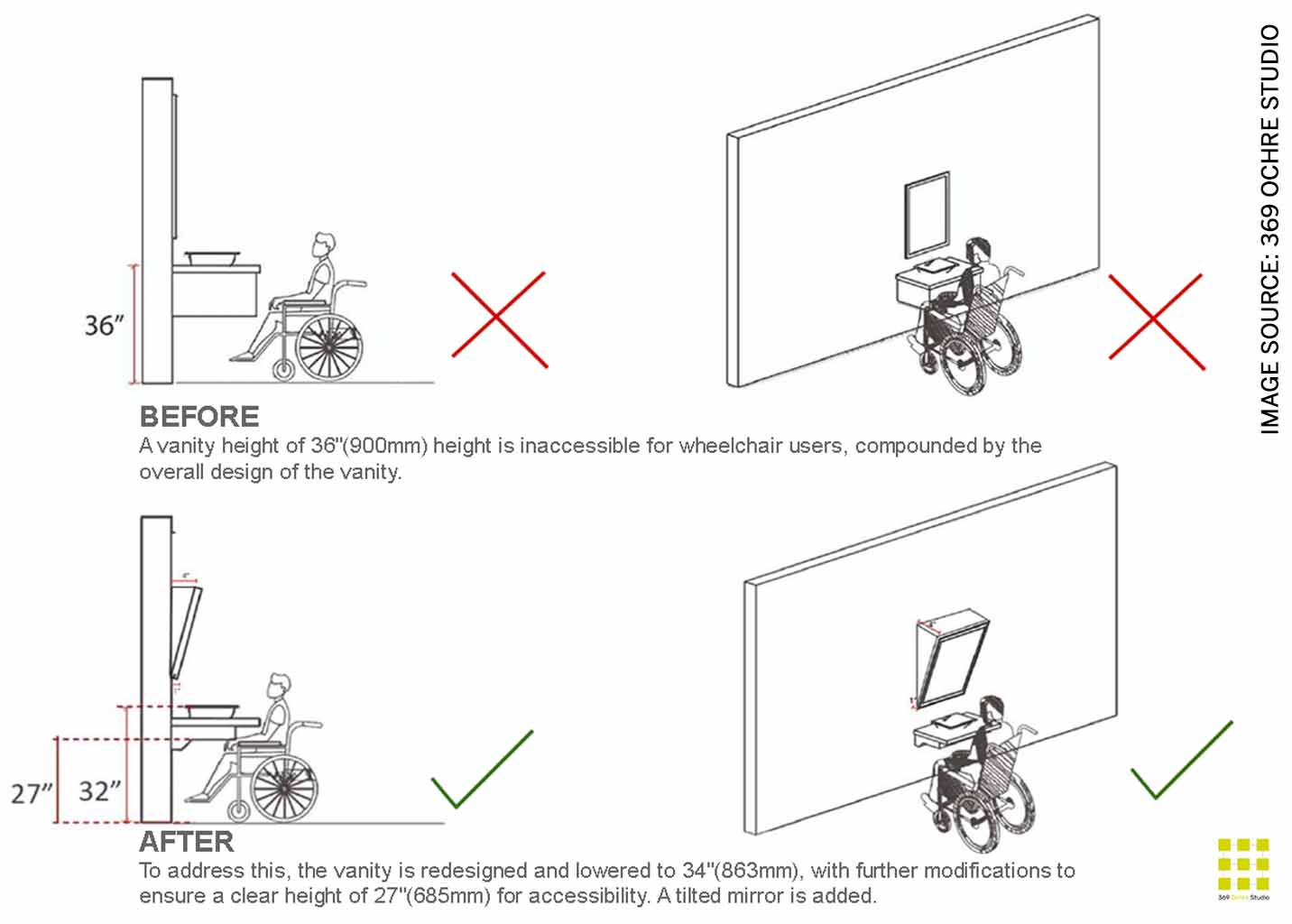

The Villa is made entirely wheelchair accessible, with interventions to introduce a ramp of a gentle gradient through modifications to the external curb to ensure a seamless approach to the main entrance. Some of the other salient features introduced were an open floor plan with wide aisle spaces that enable unobstructed movement for the son, a platform lift that connects from the living space to the upper floor corridor, extended door widths to accommodate wheelchairs and mobility aids with sliding door interventions for unrestricted movement. Some details in personal spaces included accessible toilets with attention to specificities like storage for a commode wheelchair, antiskid tiles, a tilted mirror for easy visibility of the wheelchair-user; accessible storage solutions, multi-height surfaces for wheelchair use, adaptive and automated lighting systems and ergonomic seating tailored to the clients’ anthropometric requirements.

|

In conversation with the architects of 369 Ochre Studio, they specified the importance of advocacy as a crucial part of their roles as designers, to help embed a mindset of normalising inclusion and universal design.

|

During the design and execution process, the architects were grappling with preconceived biases towards accessibility posed by the contractual team. To ease the resistance and convey the importance of these interventions, the team organised a sensitisation and capacity-building workshop for civil contractors, electrical engineers, plumbers, carpenters, and construction workers, that aimed to cultivate empathy towards Universal Design interventions, crucial for successful commencement and completion of the project.

|

As an extension of the Villa 62 project, they also organised a hands-on workshop for students and professionals of architecture and design as a dissemination effort to sensitise them towards the importance of inclusive living. In conversation with the architects of 369 Ochre Studio, they specified the importance of advocacy as a crucial part of their roles as designers, to help embed a mindset of normalising inclusion and Universal Design.

The way forward to mainstreaming inclusive living

The ‘Home Again’ Initiative by the Banyan Foundation in Chennai, is a grassroots-level initiative that “aims to normalise perceptions around mental illness by creating avenues to form healthy relationships and enable social interaction, for persons with mental illnesses”. Banyan representatives act as facilitators in the process of procuring rental residences in neighbourhoods for PwDs with varying levels of dependency. The caseworker helps build linkages with the home-owner, neighbours, and local government representatives, to ensure the presence of everyday needs, medical care, and some means of income generation for the group. Over time, Banyan has discovered that the PwDs had naturally developed healthy relationships with their surrounding community, fostering an organic support system and a positive impact on their wellbeing. Approaches like Home Again help overcome the stigma around disability and help PwDs gain acceptance and inclusion within the social fabric of cities.

Taking lessons from global models, during post-war city building in Europe, the case of deinstitutionalization in Sweden was one of the first to re-examine alternative housing solutions for PwDs. This occurred in several stages- the first involved providing community-based support, followed by support for those transitioning from an institution, and finally today PwDs can opt to live in a place of their choice and can hire support based on their needs. Acceptance in the community and social inclusion have taken nearly half a century since the inception of this model.

Facilities and approaches for PwDs must be absorbed and integrated into a larger framework, to enable various stages of transition towards achieving mainstream inclusion.

In the Indian scenario too, the model of deinstitutionalisation must begin through these various need-specific approaches. The Mental Healthcare Act (MHCA), 2017 provides for mental healthcare and protects the rights of persons with mental illness and is more progressive in its outlook than the MHA 1987, in promoting the treatment of PMI (Persons with Mental Illness). MHCA 2017’s Chapter 5- Section 19 reiterates the rights of persons with cognitive disabilities to have access to community-based facilities and calls for the need for a spectrum of transition centres. It speaks of providing facilities such as inpatient and outpatient services, rehabilitation services in the hospital, community homes, halfway homes and sheltered accommodation. Facilities and approaches for PwDs must be absorbed and integrated into a larger framework, to enable various stages of transition towards achieving mainstream inclusion.

|

It is imperative to address a top-down as well as a bottom-up approach in developing holistic models. Further, to ensure that accessibility is not just a token solution, the process of mainstreaming solutions must be participatory to include PwDs, interdisciplinary experts from the field, and NGOs working with disability in partnership with government agencies. At a policy level, legislative changes and bylaws enforcing the provision of housing for PwDs can be incentivised to encourage accessible housing models as a norm in the real estate market. In the larger sense, only when the design of residences and workplaces integrate with public spaces through Universal Design, can we envision the making of a truly inclusive city.

- With inputs from Merry Barua, Director, Action for Autism, New Delhi; Shivani Shah, Accessibility Coordinator at Vidya Sagar, Chennai; Bhagyalaxmi Madapur, Shreya Shetty- Principal Architects at 369 Ochre Studio, Bangalore.

References:

- Housing at the Centre, unhabitat.org/sites/default/files/download-manager-files/Housing_at_the_centre.pdf.

- Szporluk, Michael. The Right to Adequate Housing for Persons with Disabilities Living in Cities: Towards Inclusive Cities. United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat), 2015.

- Steinfeld, Edward, and Jordana Maisel. Universal Design: Creating Inclusive Environments. J. Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- “CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 DATA ON DISABILITY.” Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India, 2011, https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/meetings/2016/bangkok--disability-measurement-and-statistics/Session-6/India.pdf.

- “Harmonised Guidelines and Standards for Universal Accessibility in India 2021.”

https://niua.in/intranet/sites/default/files/2262.pdf

- “THE MENTAL HEALTHCARE ACT, 2017” - Ministry Of Law And Justice, Government of India.

https://main.mohfw.gov.in

Comments (0)